October 08, 2013

On September 19, in an event attended by U.S. Ambassador to Haiti Pamela White, USAID and Haitian government officials, the U.S.’ largest post-earthquake program came to its official close. According to Ambassador White, the $155 million Haiti Recovery Initiative (HRI) “is among the U.S. Government’s biggest earthquake response programs, and throughout its entire lifetime, the program has remained committed to helping Haitians rebuild their communities and work with national and local leadership to prioritize and respond to community needs.” But, as the program comes to a close, there remain more questions than answers as to what was accomplished.

In the first days after the earthquake in Haiti, USAID awarded contracts to Chemonics International and Development Alternatives Inc. (DAI), each with a value of up to $50 million dollars. The contracts were awarded through USAID’s Office of Transition Initiatives, which aims to support “U.S. foreign policy objectives…in priority countries in crisis,” according to their website. Chemonics’ contract with USAID, obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests, explains that “OTI seeks to focus its resources where they will have the greatest impact on U.S. diplomatic and security interests.” Further, while noting that “OTI cannot create a transition or impose democracy,” they can “identify and support key individuals and groups…In short, OTI acts as a catalyst for change where there is sufficient indigenous political will.”

A press release from USAID announcing the end of the program lists a number of interventions taken by OTI: provision of emergency materials to those displaced, removal of rubble, cash-for-work programs and rehabilitation of government infrastructure, among others. While the press release contains few details, quarterly and annual reports on the OTI website are supposed to provide greater detail — yet there hasn’t been an update posted in over a year-and-a-half. When asked about the lack of disclosure in December 2012, a USAID official responded that “Due to USAID’s website overhaul, more information will be available in the New Year.” No such information has been posted.

USAID Refuses to Release Info to Prevent “Demonstrations”

What information has been made public about OTI’s operations in Haiti has called into question the efficiency and performance of OTI’s contractors. In October 2012, the USAID Office of the Inspector General (OIG) released an audit on the HRI program, finding that the program was “not on track” to complete its projects on schedule. The audit also found that Chemonics was operating with little to no oversight on the part of USAID. Performance indicators were “not well-defined” and only one performance evaluation was completed despite the contract stating that “they should be conducted between two and four times a year.” A previous USAID OIG audit found that OTI was not performing internal financial reviews, despite the contractors “expending millions of dollars rapidly…in a high-risk environment.”

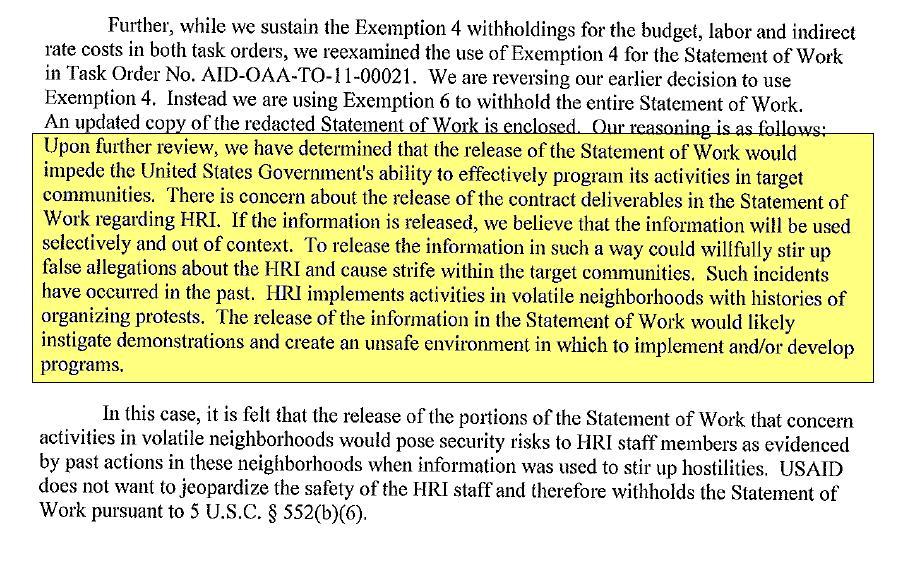

Documents obtained from Freedom of Information Act requests submitted by HRRW have redacted cost information, and the contractually mandated report on to whom Chemonics distributed funds has not been released either. After HRRW appealed the redactions, USAID responded in July, upholding their decision and in fact going even further, reissuing the document that had previously been released, with the entire Statement of Work redacted (the previous version had redacted just part of it). As can be seen in the highlighted section of the image, below, USAID justifies the lack of transparency by stating that “if the information is released, we believe that the information will be used selectively and out of context,” and that “to release the information in such a way could willfully stir up false allegations about the HRI and cause strife within target communities.” Finally, USAID notes that the “release of the information in the Statement of Work would likely instigate demonstrations and create an unsafe environment in which to implement and/or develop programs.” It is unclear how or why the projects listed in their press release would lead to such a violent reaction.

The response may refer to the last time OTI was active in Haiti, after the 2004 coup that ousted democratically-elected president Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Field Reports from USAID at the time stated that they saw the “political transition” in 2004 as having “created a new environment for collaboration with the Interim Government of Haiti,” and that “Haiti’s future depends on elections that are considered free and fair to ensure the legitimacy of the new government.” Further reports from USAID describe how they used OTI-funded programs in neighborhoods to reduce participation in protests and limit support for politicians from Fanmi Lavalas, the party of the deposed Aristide. In August 2005, USAID reported that:

OTI initiated a Play for Peace summer camp in Petit Place Cazeau, the Port-au-Prince stronghold of Lavalas Party presidential candidate Father Gerard Jean-Juste… The fruits of these efforts were seen during a recent demonstration attended by 200 people. At the same time that the demonstration was taking place, 300 people were enjoying the summer camp activities. It is believed that this camp prevented the demonstration from being larger and giving greater legitimacy to the protesters. The coming weeks will see a deepening of OTI activities in Petit Place Cazeau, where events like the summer camp will become increasingly important now that Father Jean-Juste has been arrested. His imprisonment has inflamed pro-Lavalas fires in the area and made him a martyr to some Haitians. [The document has been edited on the USAID website]

The same month, a USAID-sponsored soccer game would be the scene of a horrific massacre, when masked killers armed with guns and machetes – accompanied by uniformed police – stormed a stadium in Martissant in the middle of a match and shot and hacked at least eight people to death. The Miami Herald described the perpetrators as a new “death squad.”

OTI’s work has also been the center of controversy in Venezuela and Bolivia. Recently released diplomatic cables from Wikileaks describe a five point plan, implemented by OTI from 2004-2006 that was aimed at “penetrating [Venezuelan president Hugo] Chavez’ Political Base,” “Dividing Chavismo,” “Isolating Chavez internationally,” and “Protecting Vital US business.” It’s a similar story in Bolivia, where OTI funds aided a separatist movement that attempted to destabilize the government in 2008. Demands for information on whom USAID was supporting in those countries and throughout Latin America – and why — went unanswered. OTI offices in Venezuela and Bolivia have both been closed after pressure from those governments.

While USAID may prefer to keep their projects secret, this lack of transparency may have the consequence of fostering distrust on the ground in Haiti.