July 12, 2011

The AP’s Trenton Daniel reported over the weekend on the rise in cholera cases that have been seen since heavy rains hit Haiti early in June. Daniel reports:

The number of new cases each day spiked to 1,700 day in mid-June, three times as many as sought treatment in March, according to the Health Ministry. The daily average dropped back down to about 1,000 a day by the end of June but could surge again as the rainy season develops.

According to data from the Health Ministry, over 5600 people have now died from cholera, while over 380,000 have been sickened. In addition, throughout June, on average 8 people were dying each day, up from an average of 3.5 in May. As Daniel points out, however, “[t]he precise total is unknowable since many Haitians live in remote areas with no access to health care.”

Yet despite the renewed strength of the epidemic, there are signs that the health sector is being stretched thin:

The disease faded in winter and spring, when rain is less frequent, and many aid workers moved on. U.N. troops in Haiti turned their attention to the country’s many other pressing problems.

Now there is a fear among aid workers who remain that there won’t be enough resources if the latest surge gets much worse.

“If the cases continue on the same path we could see a lot of health-worker fatigue,” said Cate Oswald, a Partners in Health co-ordinator. “The health care force is already stretched thin.”

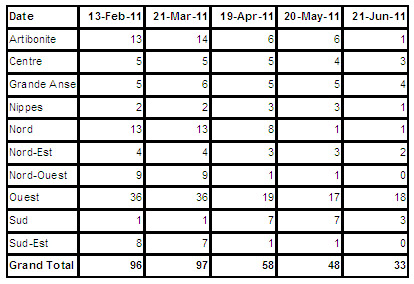

After heavy rains hit Haiti last month, the Red Cross and Doctors Without Borders (MSF), among others, issued statements saying they would be reopening cholera treatment centers (CTCs) in the capital to respond to the renewed outbreak. Updated lists released in late June by the Health Cluster, however, reveal that the decline in the number of CTCs has continued throughout the beginning of the rainy season. Table 1 shows the evolution of CTCs in each department over the last four months. The only department that saw an increase in the number of CTCs was the Ouest department, and even there it was only by one. While more than one CTC was reopened in the Ouest, nearly the entire gain was offset by the closing of other centers. Although the number of CTCs has fallen, the total capacity of cholera facilities (including CTUs) seems to be holding steady, according to partial numbers from the Health Cluster. This may be further evidence that those health providers that have continued to operate have been forced to stretch resources to make up for the exit of other organizations.

Table 1. Number of Operational CTCs

Data from Health Cluster

The number of cholera treatment units (CTUs), which are smaller than the CTCs, has stayed relatively constant (217 in March to 219 in June), while the number of Oral Rehydration Centers (ORCs), which decreased from April to May, has recently increased.

Warning Signs

At the end of March, OCHA warned that:

A Water, Hygiene and Sanitation (WASH) and CCCM Cluster analysis reveals that most of the funding to partners to support sanitation, water trucking activities and camp management will be exhausted by June 2011. As a result, it is expected that the number of humanitarian actors able to continue activities will be drastically reduced, which in turn will have serious consequences on the living conditions of camps residents. Their level of vulnerability will be particularly high due to the rain and hurricane season.

At the time of OCHA’s warning, the UN’s cholera appeal was 46 percent funded. Three months later, with a drastic increase in the number of cases, the appeal remains just 53 percent funded; an increase of just over $10 million. It costs $1 million to operate a CTC for three months. Since March, over 800 people have died from the cholera epidemic, according to MSPP data.

A recent Al Jazeera video report, also notes the initial underestimate of how bad the epidemic would be:

The Haitian government, UN agencies and non-governmental organizations, all badly underestimated the spread of the epidemic say specialists studying the outbreak.

Sanjay Basu, Epidemiologist, University of California: “Our best predictions so far show that over the next year or so that toll could rise to about 800,000 cases and 11,000 deaths. This is in a population of 10 million people, so you’re talking about almost one in ten people being directly affected by cholera.”

That initial underestimate means not enough resources were budgeted for cholera treatment and prevention.

The recent increase is especially concerning because the epidemic has become much more prevalent in the IDP camps, where hundreds of thousands remain in extremely precarious living conditions and will be especially vulnerable as the rains continue. In a statement from June 22, MSF head of mission, Romain Gitenet noted that:

During the first peak, the camps were hardly affected because there was help with latrines and distribution of chlorinated water. Since late March, the national organisation which used to distribute free chlorinated water in IDP camps began recovering costs: water is now paid for. We sounded the alarm at the time, saying that we were still in an outbreak phase. This could be in part why the camps are now infected when before they had not been.

As Michaëlle Jean, former governor general of Canada and UN special envoy to Haiti (together with Irina Bokova, the head of UNESCO) wrote at the one-year anniversary of the earthquake:

More than a million people are still living amid rubble, in emergency camps, in abject poverty; cholera, meanwhile, has claimed thousands of lives. As time passes, what began as a natural disaster is becoming a disgraceful reflection on the international community. Official commitments have not been honoured; only a minuscule portion of what was promised has been paid out. The Haitian people feel abandoned and disheartened by the slowness with which rebuilding is taking place.

Health Officials Turned Down Vaccine, WHO and Companies Say

This weekend, news also broke that late in 2010, according to the company Crucell, which manufactures the most common cholera vaccine, it had offered “tens of thousands of doses”, but the plan was rejected by health officials. One reason, as the Financial Times reports, was that the Haitian government was responding to multiple emergencies with “scant resources”. The FT continues:

Company executives said Haitian officials were under intense pressure to tackle multiple crises with scant resources following the earthquake in January last year which killed more than 230,000 people.

Peter Graaff, the current Haiti representative of the World Health Organisation, said he was unaware of the specific Crucell offer, but that a decision had been taken by the country’s health ministry at the time to reject proposals for cholera vaccination.

He questioned whether such “ring fencing” would have worked, given that it would have taken time to bring the vaccine in remote rural areas while cholera was spreading very quickly.

The vaccine requires two doses staggered a week apart, further complicating its use. At the time, Haitian officials were juggling alternative priorities including water and sanitation support, while distracted by upcoming elections.

Recently, Dr. Paul Farmer and 43 other health professionals offered their vision for a possible way forward in fighting the cholera epidemic. In their article, the health professionals call for “advocacy for scaled-up production of cholera vaccine and the development of a vaccine strategy for Haiti.” This follows a study published by The Lancet in March that found that “Vaccination of 10% of the population was projected to avert 63 000 cases (48 000—78 000) and 900 deaths (600—1500).”

Not everyone favors vaccines however. The World Health Organization and “a number of health charities oppose drug and vaccine donations, arguing that they are not sustainable and reduce the chance of low cost generic competition,” reports the FT.

Treatment vs. Prevention

Although the decline in the number of CTCs negatively affects the ability to treat cholera patients, it is clear more must be done to prevent the disease’s spread in the first place. Part of this effort is education on how to prevent cholera’s spread, but without a clean, reliable public water system Haiti will remain vulnerable to disease. Partners in Health pointed out soon after the epidemic was first reported back in October that:

While Haiti has not had a documented case of cholera since the 1960s, the conditions in the lower Artibonite placed the region at high-risk for epidemics of cholera and other water-borne diseases even before the earthquake of January 12, 2010. In 2008, Partners In Health working with partners at the Robert Kennedy Center for Human Rights released a report of the denial of water security as a basic right in Haiti. In 2000, a set of loans from the Inter American Development Bank to the government of Haiti for water, sanitation and health were blocked for political reasons. The city of St. Marc (population 220,000) and region of the lower Artibonite (population 600,000) were among the areas slated for upgrading of the public water supply. This project was delayed more than a decade and has not yet been completed. We believe secure and free access to clean water is a basic human right that should be delivered through the public sector and that the international community’s failure to assist the government of Haiti in developing a safe water supply has been violation of this basic right.

As John Carroll, a doctor at a CTC at the Hospital Albert Schweizer, notes in a recent blog post:

Cholera is indeed a horrible disease.

Ane [sic] when will this resurgence let up? Will it slow down at the end of the rainy season and then take off again with a tropical storm or hurricane that strikes after the rainy season is over?

And cholera is now endemic in Haiti. So will this all happen again with 2012’s rainy season?

And cholera statistics are important but they seem kind of unimportant to me now. When asked how many new cholera patients we saw on a certain day I say “alot”.

Aren’t the real questions:

What are skilled men and women upstream doing to separate the good water from the bad water? Isn’t that the important thing to know? If that were happening there would be no downstream problem with cholera. And we wouldn’t have to worry about silly things like NGOs, Ringer’s Lactate, cholera tents, and begging for buckets.

If upstream changes don’t occur soon, thousands more grown Haitian men and women will be shuffling around with “zombiefied” looks clothed only in diapers.