November 23, 2015

The usually astute Greg Ip gets derailed in a high production values piece that tries to tell us that our problems stem from not having enough kids. For those left scratching their heads while sitting in traffic jams or standing in over-crowded subway cars, the basic story is that we somehow don’t have enough workers to do all the work. (Where are those damn robots when we need them?)

Anyhow, the piece starts out quickly on the wrong foot:

“Ever since the global financial crisis, economists have groped for reasons to explain why growth in the U.S. and abroad has repeatedly disappointed, citing everything from fiscal austerity to the euro meltdown. They are now coming to realize that one of the stiffest headwinds is also one of the hardest to overcome: demographics.”

Umm no, those of us who warned of the housing bubble and predicted that the resulting downturn would be hard to reverse saw the weak growth as a 100 percent predictable problem from a shortfall in aggregate demand. There was no source of demand to replace the construction and consumption demand driven by the bubble.

And, I don’t recall being at all troubled by slower aggregate growth, the issue was that we were seeing insufficient growth to fully employ the population. The United States and many other wealthy countries have seen a sharp decline in the employment to population ratio. This is true even when we look at the employment to population ratio for prime age (ages 25–54) workers. This is down by three full percentage points from its pre-recession peak and by more than four percentage points from its 2000 peak. It is pretty hard to explain the drop in the percentage of people working by demographics.

We later get the strange statement:

“Simply put, companies are running out of workers, customers or both. In either case, economic growth suffers.”

Actually, these are two very different stories that need to be considered separately. Suppose companies don’t have enough customers. This is a story of inadequate demand. How do we solve it? Spend money. The private sector can do it, the government can do it, counterfeiters can do it. In this story, more demand will create more supply. The only obstacle to generating the demand is our own stupidity. (We can also all decide to work fewer hours, since we are producing more than we need, we should be able to all work less and still meet our needs.)

The story of too few workers is a story of inadequate supply. We have needs that we just can’t meet because there is no one to do them. The problem with this story is that it only focuses on half of the equation, and by far the less important half. The ability of the working population to meet the needs of the total population depends on both the size of the workforce relative to the whole population and also its productivity. The productivity portion of the story swamps the population portion of the story.

Here’s what I wrote in response to a Washington Post piece on China earlier in the month.

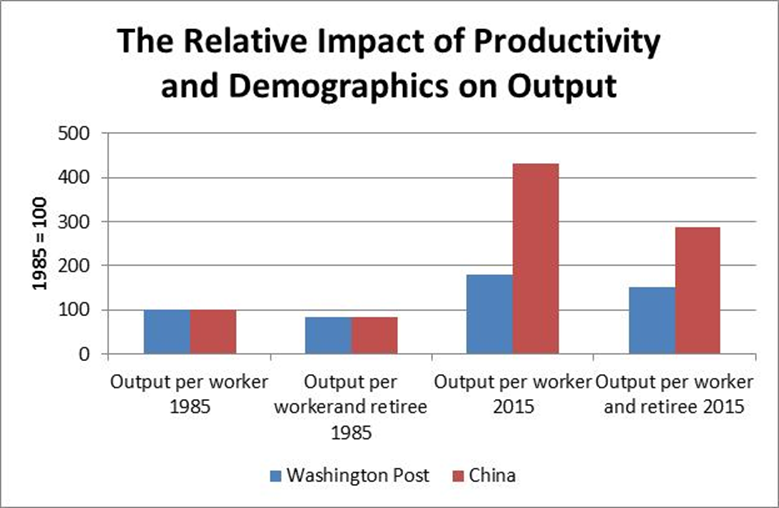

“To see why this is not true, we will take a very simple story where we contrast a country with moderate productivity growth and no demographic change with a country rapid productivity growth and a rapid aging of its population. The figure below shows the basic story.

Source: Author’s calculations.“We assume that in 1985 there are five workers to every retiree in both the Washington Post and China story. If we set output per worker in 1985 equal to 100, then the amount of output per worker and retiree in 1985 is 83.3 (five sixths of the output per worker). We then allow for different rates of productivity growth and population growth over the next three decades.

“In the China scenario, we have 5.0 percent annual productivity growth. This is somewhat slower than the actual rate of growth of output per worker over the last three decades, but it is still sufficient to make the point. The calculation assumes the ratio of workers to retirees falls to just two to one, a sharper decline than has actually been the case.

“In the Washington Post scenario, we assume a moderate 2.0 percent rate of productivity growth, roughly the average rate for the U.S. economy over the last three decades. To make the case extreme in the other direction, it is assumed there is no change in the ratio of workers to retirees so that in 2015 the ratio is still five to one.

“As should be obvious, in the high productivity case output per worker is far higher in 2015 than in the Washington Post scenario. Output per worker reaches 432.2 in 2015 in the China scenario, compared to just 181.1 in the Washington Post scenario.

“Because of the extraordinary differences in output per worker, China is still much better capable of supporting its retired population in 2015 than a country following the Washington Post scenario. Its output per person is equal to 288.1 in 2015. This means that both its workers and retirees can enjoy an income that is 188.1 percent higher in 2015 than it was in 1985. By contrast, in the Washington Post scenario output per person in 2015 is just 150.9 in 2015, meaning that its workers and retirees can only enjoy an income that is on average 50.9 percent higher than in 1985.

“In this case, it should be evident that China will have a much easier time supporting its retirees than a country that had enjoyed just moderate productivity growth and no demographic change. It is also worth noting that some demographic change was inevitable. Regardless of what policies China had pursued it was going to see an aging of its population, which would have meant a decline in the ratio of workers to retirees.

“These numbers also overstate the benefits of the Washington Post scenario for two other reasons. The numbers treat retirees as the only dependents. Of course there are also children. The ratio of children to workers would be far larger in the Washington Post scenario than in the China scenario. Incorporating children into the calculation would further increase the gap in the change in output per person between the two scenarios.

“The other difference is that the Washington Post scenario of more rapid population growth would imply much greater strains on China’s natural resources. The country would require much more food and water and emit a much larger amount of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. This would further reduce the standard of living in the Washington Post scenario relative to the China scenario shown here.”

In short, China is actually extraordinarily well-prepared for the aging of its population. It should in principle have no problem generating enough output so that both its workers and retirees can enjoy much higher standards of living in ten years than they do today. (This does require setting up a good public pension system.) Countries with a slower rate of aging but worker productivity growth will find this more difficult.

In keeping with the confusion throughout the piece we also get the complaint that builders are suffering from a shortage of labor:

“For example, home builders are simultaneously suffering from shrinking demand since the homeownership rate is declining, and from labor shortages as the baby boomers retire.”

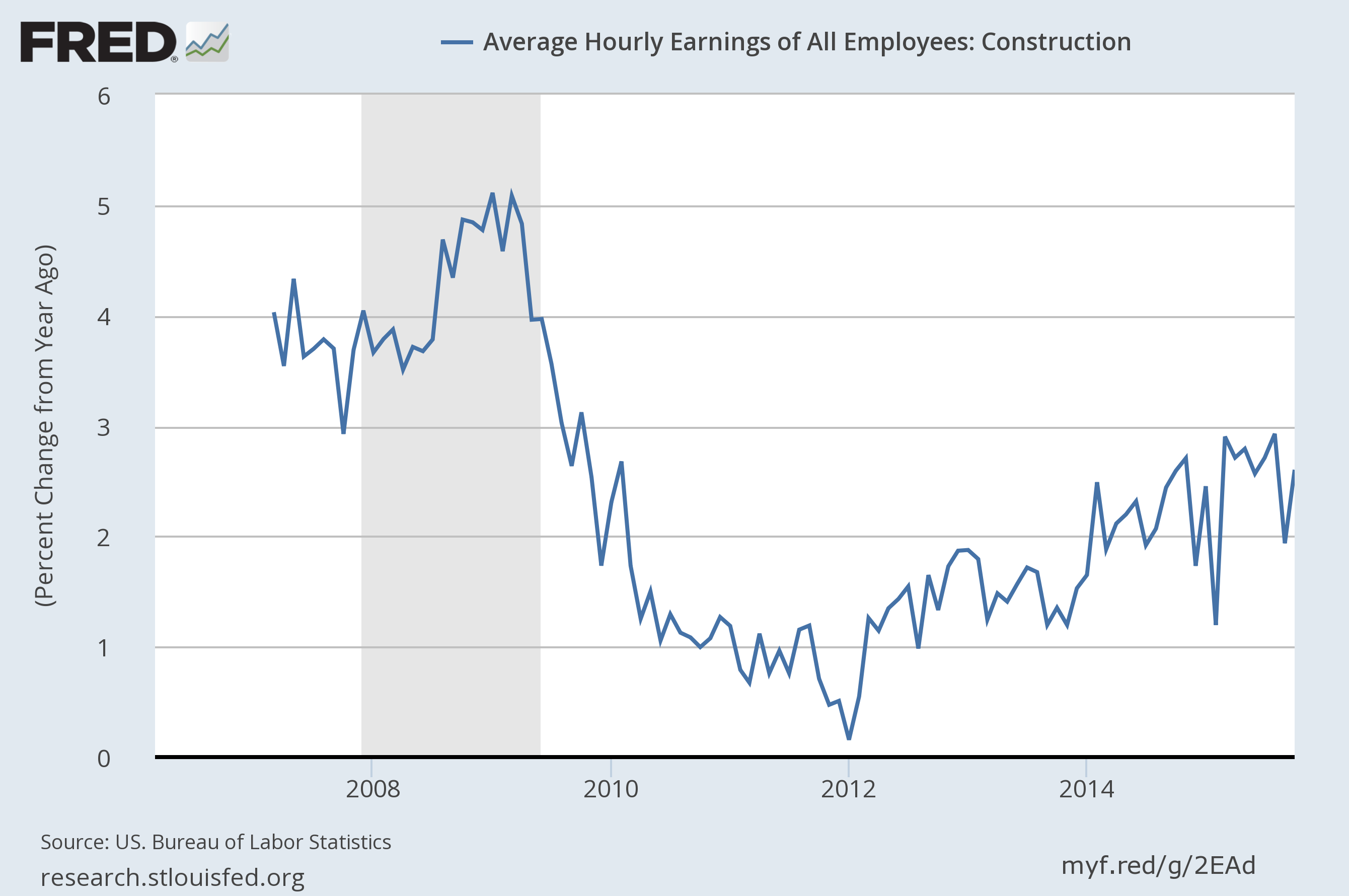

A shortage of labor would imply construction workers’ wages are rising rapidly. They aren’t.

There is some uptick in the rate of nominal wage growth, but it remains below 3.0 percent annually, which is well below pre-recession levels. In short, not much evidence of a shortage here.

Just to repeat, the question we have to ask is whether the problem is a shortage of demand or supply. If the problem is demand, then we can easily deal with it. If the problem is supply then we have to explain why in the era of computerization and robots we aren’t seeing productivity growth. If the economy is broken and unable to sustain productivity growth, this is the real problem. Getting more people to make our cities and natural spaces more crowded is not the solution.

Comments