August 18, 2017

There is a recurring theme in public discussions, seemingly embraced by everyone from Steve Bannon to columnists at the New York Times and Washington Post, that we should use protectionist measures to try to keep China from overtaking the U.S. as the world’s leading economic power. This effort is both incredibly wrongheaded and doomed to failure.

In terms of it being wrongheaded, the people doing the China bashing don’t even understand that they are being protectionist. Heather Long tells readers in the Washington Post:

“The real issue is that the Chinese are pirating American ideas and technologies. In the 1990s and early 2000s, people were worried about China illegally copying movies, music and books. The stakes are a lot higher now as the world’s top economies compete on groundbreaking technologies in cloud computing, robotics, artificial intelligence and gene editing. Whoever controls these technologies will dominate global business — and more.”

Okay, great diatribe here, but let’s try some serious thinking instead. What exactly makes them “American ideas and technology?”

I know, we say so. But once an idea comes into the world or technology is developed, it is really there for the taking. We have rules on patent and copyright protection that say they are “American,” but why should China or anyone who believes in free markets give a damn?

Bannon, Long, and others want the United States to get tough with China (trade war!) to make it honor our protectionist rules on ideas and technology, but there is no obvious reason that most of us should go along with this crusade. Suppose we sit back and let China continue with its evil plans. In a few years, they will be flooding the world with low-cost cloud computing, robots, airplanes and who knows what else? The horror, the horror!

But what will happen to our tech giants like Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, and the rest? In this story, they fall into the second rank of firms, like Italian software companies today. I’m sure that this looks really bad to the top executives and major shareholders of these companies, but why should the 90 plus percent of the population who are neither give a damn? For the rest of us, getting all of this neat technology really cheap from Chinese companies sounds really good, just like we have been told it was really neat to get cheap clothes, steel, and car parts from China. If there’s a difference here, no one has made a clear case as to why.

There is, in fact, an issue here that is worth discussing, if we can drop the China bashing. Our rules on intellectual property are hopelessly antiquated. Patent monopolies might have been great for the medieval guild system, but they are not a very good way to support innovation in the 21st century. We should be working on developing an international system for supporting innovation and creative work that does not depend on these archaic forms of protectionism.

This doesn’t mean a system that will maximize Microsoft and Apple’s profits, it means a system that supports open innovation that allows the whole world to benefit. If we put in place such a system we need have no fear that Chinese firms will “control” new technologies since no one will control them. (This paper I wrote with Arjun Jayadev and Joe Stiglitz has some ideas.)

While it will be difficult to shift our policy on trade and innovation in a direction that benefits the bulk of the public rather than the tech giants, a little clear thinking on our efforts to contain China may be helpful. Using purchasing power parity measures of GDP, which most economists consider the best basis for comparison, China’s economy is already almost 20 percent larger than the U.S. economy according to the I.M.F. It is projected to grow at a 5.9 percent annual rate over the next five years compared to a rate of less than 2.0 percent for the United States.

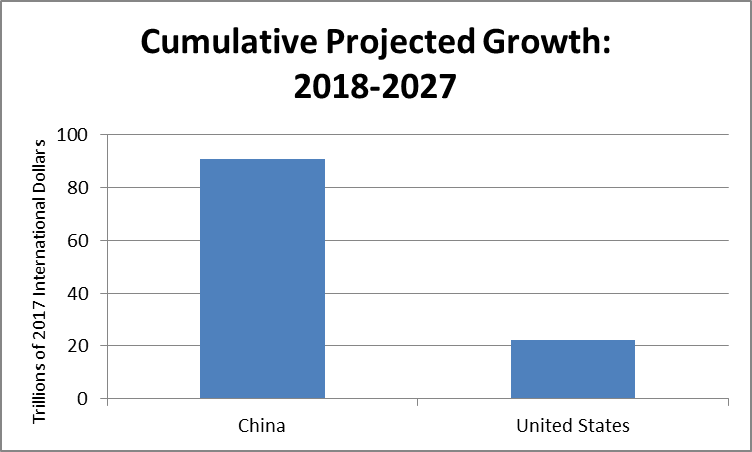

If we project these growth rates out for a decade, China’s cumulative increase in GDP between 2018–2027 will be 90.5 trillion international dollars. The cumulative growth in the U.S. over this period will be 22.2 trillion international dollars.[1] China’s GDP in 2027 will be almost twice as large as that of the U.S.

A little common sense is in order here. The country that is half the size will not be dictating policy to the country that is twice the size. There is actually a noteworthy precedent for such an effort. Much of the early industrialization of the U.S. involved technology that was “stolen” from the United Kingdom. Our early factory owners smuggled blueprints for steam engines out of the UK in violation of their Official Secrets Act. We also didn’t respect the UK’s copyrights for most of the 19th century.

Anyhow, these efforts by the UK to claim ownership of ideas and technology proved futile, as would likely be the case with U.S. efforts against China. We should be looking to develop systems of supporting innovation that offer the widest possible benefits while the United States is still a leading actor in the world. Unfortunately, the power of the tech industry (did I say the “Amazon-Washington Post?”) makes this shift in policy very difficult.

[1] This calculation uses the projected GDP growth rate for each country in constant units of their own currency and applies it to the I.M.F’s 2017 estimate for purchasing power parity GDP measured in international dollars. It then sums the growth for each country, compared with the 2017 GDP.

Comments