November 09, 2017

November 2017, Dean Baker

Presentation by Dean Baker at “What is the Future of International Trade?” Workshop at the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver

November 3, 2017

In the United States and many other countries, much of the population has turned against trade. It was a major issue in the 2016 election and was an important factor in putting Donald Trump in the White House. The hostility toward trade should not be surprising. There is good evidence that large segments of the U.S. population have been hurt by the pattern of trade over the last four decades (Autor, Dorn, and Hansen 2016; Bivens 2013). In particular, workers without college degrees were the losers, as they were forced to compete with much lower paid workers in the developing world. Whatever gains may have come from comparative advantage were more than offset by the losses they suffered from a weakened bargaining position.

While this has been the reality over the last four decades, there was certainly nothing inevitable about the harm done to less-educated workers. The upward redistribution from trade was not the result of an impersonal process of globalization; it was the result of deliberate policy. It would have been possible to design trade policies that benefited those at the middle and bottom at least as much as those at the top. The fact that trade policy did not take this course reflects the relative political power of different groups.

In this discussion, I will briefly outline a path for trade policy that would not lead to upward redistribution.[1] Before getting to the specifics it is important to point out that this is not a question of pitting manufacturing workers in rich countries against manufacturing workers in poor countries where one group must inevitably be the losers. While this has been a popular way to portray the issue in the media (see Beauchamp 2016; Weissman 2016, Lane 2016; and Zakaria 2016), it is wrong. There is not an inherent conflict of interests between workers in rich countries and poor countries, even if it is convenient for many to frame the issue this way.

I will focus on three major topics in trade policy:

-

The macroeconomics of trade: It is common for economists to argue that we should not worry about trade deficits hurting output and employment since monetary policy can easily offset any demand lost due to a trade deficit. This may have been a plausible argument in the years prior to the Great Recession. Now that most economists recognize that “secular stagnation”

can be a real problem, the notion that the demand shortfall created by a trade deficit can be offset in any easy way is clearly wrong.

-

Which items are traded: A major goal of trade deals over the last three decades has been to remove barriers to trade in manufactured goods, making it as easy as possible to import manufactured items from the developing world into the United States. This was a policy choice that had the effect of putting our manufacturing workers in direct competition with low-paid workers in the developing world. We could have constructed trade deals to put doctors, dentists, and other highly paid professionals in direct competition with their lower-paid counterparts in the developing world. The argument for this sort of trade in professional services is the same as the argument for trade in manufactured goods, except the main beneficiaries would be lower paid workers, rather than the most highly paid workers and owners of capital.

-

Intellectual Products, Free Trade Rather than Protectionism: A major focus for the United States in its trade deals of the last three decades has been to impose longer and stronger protections for intellectual property in the form of patents, copyrights, and other types of government granted monopolies. This has the explicit purpose of transferring more income to those in a position to benefit from ownership of these monopolies at the expense of the rest of society. It is possible to design trade deals that foster the free transfer of knowledge and rely on more modern mechanisms to pay for innovation and creative work.

Altering the direction of trade deals in these three areas would lead to patterns of trade which would foster overall growth and benefit the bulk of the society in both rich and developing countries. This alternative path would make trade a force for equality rather than inequality. For this reason, the policies outlined here would face enormous obstacles in practice. However, we should be clear: the obstacles are political, not economic.

The Macroeconomics of International Trade: What Happened to Rich Countries Exporting Capital?

In the standard textbook story, trade is supposed to result in a situation in which countries export the factor(s) that is relatively plentiful and import what is relatively scarce. This used to be taken to mean that rich countries should be net exporters of capital since they have more capital than developing countries. This would mean that they would be running a deficit on their capital account, as capital

flowed to developing countries and a surplus on their current account. That is the opposite of the situation we have seen over the last two decades.

The logic for this pattern of capital and trade flows is that rich countries would be providing the capital that developing countries need to build up their private capital stock and infrastructure while they also struggle to meet the basic consumption needs of their populations. The trade deficits run by poor countries allow them to consume more than they produce.

The mechanism that brings about this happy situation is that fast-growing developing countries should provide a higher rate of return on capital than slow growing rich countries. This leads firms in rich countries to want to invest directly in poorer countries, building factories, stores, office buildings and other types of direct investment. In addition, the return on financial investment should also be higher in developing countries, so that banks, pension funds, and other holders of capital should be willing to buy public and private assets issued by developing countries.

This story actually provided a reasonably good description of trade between poor and rich countries in the 1990s, until the East Asian financial crisis in 1997. While the United States had modest trade deficits over this period (around 1.0 percent of GDP), Europe and Japan had large surpluses. Most developing countries had large trade deficits, with the ones in East Asia having especially large trade deficits. This was also a period in which the East Asian countries experienced extraordinarily rapid growth.

To take two striking examples, in the years from 1990 to 1997 Indonesia and Malaysia had annual growth rates of 7.8 percent and 9.6 percent, respectively. Their average trade deficit in this period was just over 2 percent of GDP in the case of Indonesia and almost 5 percent of GDP in Malaysia.

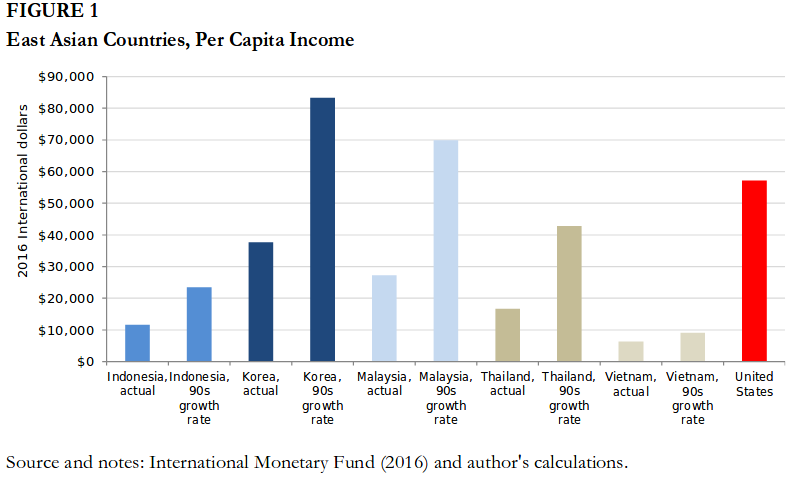

The trade deficits run by several of the East Asian countries during this period probably were excessive, and their pattern of growth was not entirely sustainable, but the idea that developing countries cannot grow rapidly without running large trade surpluses is absurd on its face and is contradicted by the growth these and other East Asian countries experienced in the 1990s. Had this pace of growth continued to the present, these countries would be far richer today than is actually the case. In fact, two of the countries, South Korea and Malaysia, would actually be richer than the United States if their growth rate of the pre-crisis 1990s had continued, as shown in Figure 1.

The East Asian financial crisis was set off by a crisis of confidence which first hit Thailand in the summer of 1997 and then quickly spread to the other countries of the region. The inflow of capital from rich countries slowed or reversed, making it impossible for the developing countries to sustain the fixed exchange rates most had at the time. One after another, they were forced to abandon their fixed exchange rates and turn to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for help.

Rather than promulgating policies that would allow developing countries to continue the textbook development path of growth driven by importing capital and running trade deficits, the IMF made debt repayment a top priority. The bailout, under the direction of the Clinton administration Treasury Department, required developing countries to switch to large trade surpluses (Radelet and Sachs 2000).

In the wake of the East Asia bailout, countries throughout the developing world decided they had to build up reserves of foreign exchange, primarily dollars, in order to avoid ever facing the same harsh bailout terms as the countries of East Asia. Building up reserves meant running large trade surpluses. It is no coincidence that the U.S. trade deficit exploded over this period, rising from just over 1 percent of GDP in 1996 to almost 6 percent in 2005.

There was no reason the textbook growth pattern of the 1990s, with developing countries being importers of capital, could not have continued. It wasn’t the laws of economics that forced developing countries to take a different path; it was the failed bailout and the international financial system. There was no need for the sort of mass destruction of manufacturing jobs that the United States experienced due to trade in the decade from 1997 to 2007. If the textbook pattern of growth had continued, manufacturing output in the developing world could have been largely an addition to global output rather than a replacement for manufacturing output in the United States and elsewhere.

The key issue is allowing currencies to adjust in value so that fast-growing developing countries are not running massive trade surpluses. This means having a set of rules that limit the extent to which countries can depress the value of their currency in order to maintain a trade surplus. This should be a doable task, in spite of efforts by many to make it sound impossibly complicated. Monitoring currency purchases by central banks and governments is a much easier assignment than many issues that routinely arise in trade negotiations.[2]

It is important to remember in this context that for a developing country a higher valued currency should be a net positive. It means that it would be paying less for the goods and services it imports, which should mean that its population would be able to enjoy a higher standard of living. There is an issue of whether developing countries can feel secure in running trade deficits. The experience of the East Asian countries dealing with the I.M.F. in the financial crisis and later in the decade Russia, Brazil, and Argentina, provides developing countries with good grounds to be fearful. As a result, they could very reasonably want to hold larger stocks of reserves than might seem appropriate, but if the I.M.F. can exhibit good behavior and/or alternative sources of financing like China show themselves willing to fill the gap, we may see flows of capital and trade again follow the textbook pattern.

Trading Doctors In Addition to Steel

The current pattern of trade has exposed manufacturing workers to competition with their much lower paid counterparts in the developing world, thereby driving down their pay and the pay of less-educated workers more generally. This is typically viewed as a natural, if unfortunate, outcome of free trade. It costs less to produce manufacturing goods in the developing world, therefore if we reduce the barriers to trade, we will naturally import more manufactured goods from the developing world.

That story is true, but it also costs much less to train a doctor, dentist, or other professional in the developing world than in the United States. If we eliminated the barriers to trade in professional services, allowing qualified foreign professionals to work in the United States, we would both see substantial overall economic gains from having access to lower-paid professionals, and also less inequality since this would put downward pressure on the wages of some of the country’s most highly paid workers. The decision to remove barriers to importing steel and shoes, but not removing barriers to foreign physicians and dentists practicing in the United States was political, reflecting the relative power of the most affected groups, it was not determined by economics.

If we treated professional services in trade agreements the way we treat manufactured good, we would be looking to determine a set of standards necessary to practice a profession in the United States, and then work to set up rules that make it as easy as possible for people in other nations to train to these standards and then practice their profession in the United States. This could mean in the case of doctors, for example, that we have a well-defined set of courses that doctors would be expected to take, and hours of clinical experience in various areas they would need to complete, in order to be qualified to practice in the United States. They would also have to take the same sort of tests to get a license in the United States, although to reduce the cost for aspiring foreign physicians it should be possible for them to take a test in their home country, with testers who are authorized by the United States. Once a person in a partner country has completed their training and passed their exam, they should have the same rights to practice in the United States as a person who was born and trained in the United States.

The potential benefits to the United States from an opening of trade in professional services are enormous. Doctors in the United States earn on average more than $250,000 a year, net of expenses like malpractice insurance. Their counterparts in other wealthy countries earn roughly half as much on average.[3] With over 900,000 practicing physicians in the United States, if their pay can be reduced by an average of $100,000 the savings would be around $90 billion a year, almost 0.5 percent of GDP. There would be comparable, albeit smaller, savings in other highly paid professions. (Dentists in the United States also make roughly twice as much as their counterparts in other wealthy countries. Reducing their pay to the average in other rich countries could add another $10 billion to the annual savings.)

The impact of bringing in more foreign workers in the highest paying professions should also have a substantial impact on equality, by lowering the pay of workers in the top 2.0–3.0 percent of the wage distribution. Just as the loss in pay and employment by manufacturing workers had a negative impact on the pay of less-educated workers more generally, the competition from more foreign workers in the highest paying professions should put downward pressure on the wages of highly paid workers more generally.

It is important to realize that this is really much more an issue of professional licensing restrictions than immigration. The current pace of immigration is around 1.4 million a year. If just 5 percent of this flow was diverted from people coming here to work in construction and hotel kitchens to people working as doctors and in other high-paying professions, it could completely transform these professions over the course of a decade. Alternatively, this additional influx of professionals (currently roughly 20 percent of doctors are foreign-born) could be filled with a very modest increase in total immigration flows.

To ensure gains on both sides, it is important that other countries, especially developing countries, be compensated for the loss of trained professionals. This sort of redistribution from winners to losers would actually be much simpler than the type economists usually like to advertise as a correction for inequities resulting from expanded trade. Since the issue here is one of an influx of licensed professions, it is possible to determine with a fair degree of precision the winners and the size of the winnings. We also know the losers, the countries that trained the professionals that came to the United States. If we imposed a tax on the earnings on foreign-trained professionals and sent the revenue collected back to their home country, it should be possible for them to train two or three professionals for every one that comes to the United States.[4] This would ensure that the developing countries that train professionals who end up working in the United States end up as winners as well.

There is no principled reason why trade deals cannot focus on facilitating the flow of highly trained professionals across international borders. This has already been accomplished to a substantial extent within the European Union. Increasing this flow has not been a priority in U.S. trade deals because the highly paid professions have enough political power to ensure continuing protection from foreign competition. However, a goal of progressive trade policy should be that doctors and other highly paid professionals get to enjoy the benefits of international competition in the same way as textile workers and steel workers.

Free Flow of Knowledge and Information as an Alternative to Ever Stronger Intellectual Property

A major goal of the United States in trade deals over the last three decades has been requiring its trading partners to have longer and stronger patents, copyrights, and related forms of protection. These forms of protection can raise the price of the protected items by many thousand percent above the free market price. They are especially important in the case of prescription drugs. The generic versions of drugs are almost always cheap, as they cost little to manufacture. By contrast, patent monopolies can allow drug companies to charge tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars for drugs that would be available for a few hundred dollars in a free market.[5]

The ostensible rationale for imposing these protections in trade deals is to provide more incentive for innovation or creative work in the case of copyright. The impact of these incentives is questionable (in the case of copyright, the U.S. has typically demanded that the extension be retroactive so that works that were created decades ago would now enjoy longer copyright protection), but there is no dispute about the effect of these protections on prices. And, at least in the case of prescription drugs, the higher prices can be a serious threat to public health since important drugs may no longer be affordable for people in developing countries.

We should be willing to recognize the patent and copyright systems for what they are: archaic relics of the medieval guild system. Instead of making ever more convoluted rules around these forms of protection to adapt them to the 21st century, we should be developing more modern and efficient mechanisms to support innovation and creative work. The basic problem is that once an innovation has taken place or an artistic work has been created, the cost of transferring it is nearly zero. This means that the innovator or creative worker will be unable to recoup the cost of their efforts through a normal market price. Instead of solving this problem by granting monopolies, the government can look to pay for this work directly and then allow it to be transferred without restrictions.

There are a variety of mechanisms that can be used to finance innovation and creative work, many of which are already in use. In the case of prescription drugs, the United States government already spends more than $30 billion a year on biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other government agencies.[6] While most of this money goes to more basic research, NIH funding has led to the development of many important drugs. It also has supported a large number of clinical tests. There is no reason in principle that public funding could not be expanded to replace the research now being supported by patent monopolies.

An advantage of publicly financed research over research supported by patent monopolies is that all research findings could be immediately available to other researchers. In fact, this can and should be a condition of receiving support. This should facilitate the development of effective drugs as the timely sharing of information should allow researchers to build on each other’s successes and learn from their failures. It should also take away the incentive in the patent system for duplicative research since there would be no payoff to working around an existing patent in order to get a share of a drug’s patent rent.

In addition, if companies were paid for their research upfront rather than relying on patent monopolies to recoup the costs, they would have no incentive to mislead the public about the safety and effectiveness of the drugs they developed. This is a major problem, especially in the United States where drug companies are allowed to market directly to patients. Drug companies have an enormous incentive to promote drugs in situations where they may not be appropriate and to conceal evidence that raises questions about their effectiveness and safety.[7]

The other obvious advantage of this sort of system is that all new drugs could be sold at generic prices since the research had already been paid for. In this situation, virtually all new drugs would be affordable to all but the very poor. And even in this case, generic drug prices should make it possible for aid agencies to provide most medicines to the world’s poor.

It would be reasonable to have a cost-sharing mechanism included as part of trade deals. While the details of a mechanism would undoubtedly be complicated, the basic principles should be reasonably straightforward. We would want to set up a progressive payment structure in which countries contribute roughly in proportion to their GDP. For example, the richest countries may be expected to pay 1.0 percent of GDP to support the development of new drugs, medical equipment, and creative work through various channels. Middle-income countries may be expected to spend 0.5 percent of their GDP, while the poorest countries may be expected to make some form of token contribution.

There also would have to be agreed upon procedures for how the payments are made in order to ensure that countries don’t simply make their payments to politically connected individuals or firms.[8]

In the case of creative work like books, movies, and recorded music, countries could allocate vouchers to their citizens to allow them to support whatever creative workers or organizations they choose. The tax deduction in the U.S. tax code for charitable contributions provides a useful model for this sort of system. The tax deduction effectively amounts to a government subsidy to the charities chosen by individuals, which can be as high as 40 percent for high-income individuals.[9] Instead of a deduction, the government could provide a modest credit that individuals could use to support the creative worker(s) of their choice or an organization that is dedicated to supporting creative work. The latter could, for example, a publisher of mystery novels, a producer of jazz music, or a production company focused on movie comedies.

The condition of getting funding through this system is that the creative worker is ineligible for copyright protection so that everything they produce is immediately in the public domain where it can be freely transferred over the web. Individuals and organizations would have to register to get funds in the way that charitable organizations in the United States must register to get tax exempt status. In assessing an application by a charitable organization, the Internal Revenue Service doesn’t attempt to assess the quality of a religion or a think tank, they just make a determination of whether what the organization claims to do qualifies for non-profit status. Continuing the qualification for non-profit status just requires that they are engaged in the activity they have listed.

This would be the same criterion for individuals and organizations that qualify for receiving funding through the voucher system. The rule on not being eligible for copyright protection has the benefit that it is self-enforcing. A person who took money through the voucher system and then tried to claim copyright protection would be unable to enforce the copyright since the receipt of money from the voucher system would make the copyright invalid.

This sort of voucher system could make a vast amount of creative material available at zero cost over the Internet. Instead of resources being devoted to preventing people from having access to material, it would be in the interest of creative workers to have their work spread as widely as possible since this would increase their ability to get support through the system. Here also there could be rules in trade agreement for countries to make commitments of a percentage of their GDP on a progressive basis to this sort of system. This might be a more growth-enhancing path than the current route requiring longer and stronger protections and more draconian laws for violators.

Of course, there are other mechanisms that could be designed to support innovation and creative work (see Baker, Jayadev, and Stiglitz 2017). The point is that there are alternatives to the patent and copyright systems. We should look to construct trade deals that rely on these alternatives rather than making patent and copyright and related protections ever stronger.

Conclusion: The Path of Globalization Is Determined by Policy, not Nature

The argument presented here is that the bad outcomes from globalization for large segments of the working class in the United States, and to a lesser extent other wealthy countries, were determined by policies that were designed to redistribute income upward. They were not an inevitable outcome of globalization.

Specifically, it is possible to envision a pattern of trade that follows the textbook model, in which rich countries run trade surpluses with developing countries. This would have prevented the mass displacement of manufacturing workers seen in the United States and other wealthy countries over the last two decades.

It is also possible to envision trade in highly paid professional services. This would subject a rich country’s doctors and dentists to competition with their much lower paid counterparts in the developing world. This would provide large economic gains to the country, just as has trade in manufactured goods, but it would be associated with reduced inequality rather than increased inequality. It is also possible to design compensation mechanisms that ensure developing countries benefit as well from training professionals to work in rich countries.

And, contrary to the pattern in recent trade deals, which have sought longer and stronger patent and copyright protections, new rules can be designed to facilitate the free flow of innovation, creative work, and knowledge. This would be real free trade. We need more modern mechanisms to finance innovation and creative work and a system that ensures a fair sharing of the cost. The system of patents and copyrights is an archaic relic of the medieval guild system that becomes ever harder to enforce in the Internet Age.

It is probably worth mentioning rules on labor standards, which are often discussed as part of a progressive trade agenda. It would be desirable to have rules on basic standards, such as a right to unionize, bans on prison labor, a minimum wage linked to a country’s level of GDP, included in trade deals. Such rules can ensure basic standards for workers in our trading partners. However, it is a mistake to imagine that the lack of such rules is a major factor in the impact of trade on inequality in rich countries.

Workers in China and other developing countries would still be paid far less than workers in the United States even if they had full rights to organize. These are much poorer countries and they will have to go through a lengthy process of development to attain the living standards of the rich countries. For this reason, it is definitely good policy for the United States and other rich countries to promote labor rights in developing countries through trade deals, but it is wrong to imagine that this is the solution to the inequality generated by the pattern of trade we have seen over the last four decades.

References

Autor, David, David Dorn, Gordon Hanson. 2016. “The China Shock: Learning from Labor Market Adjustment to Large Changes in Trade.” Cambridge, MA: NBER Working Paper No. 21906.

Baker, Dean. 2016. Rigged: How Globalization and the Rules of the Modern Economy Were Structured to Make the Rich Richer. Washington, D.C.: Center for Economic and Policy Research. http://deanbaker.net/images/stories/documents/Rigged.pdf.

Baker, Dean, Arjun Jayadev and Joseph Stiglitz. 2017. “Innovation, Intellectual Property, and Development: A Better Set of Approaches for the 21st Century.” Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/images/stories/reports/baker-jayadev-stiglitz-innovation-ip-development-2017-07.pdf.

Beauchamp, Zack. 2016. “If you’re poor in another country, this is the scariest thing Bernie Sanders has said.” Vox.com, April 5. http://www.vox.com/2016/3/1/11139718/bernie-sanders-trade-global-poverty.

Bivens, Josh. 2013. “Using Standard Models to Benchmark the Costs of Globalization for American Workers Without College Degrees.” Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute. http://www.epi.org/publication/standard-models-benchmark-costs-globalization/.

International Monetary Fund. 2016. “Report for Selected Countries and Subjects.” Washington, D.C.: IMF. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2016/01/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=20&pr.y=13&sy=2004&ey=2021&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=924&s=BCA_NGDPD&grp=0&a=.

Katari, Ravi and Dean Baker. 2015. “Patent Monopolies and the Costs of Mismarketing Drugs.” Washington, D.C.: Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/publications/reports/patent-monopolies-and-the-costs-of-mismarketing-drugs.

Lane, Charles. 2016. “The Sanders-Pope ‘Moral Economy’ Could Hit the Income Inequality Fight.” Washington Post, April 13. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-sanders-pope-francis-moral-economy-could-hurt-the-income-inequality-fight/2016/04/13/8007b80a-01ae-11e6-9203-7b8670959b88_story.html.

Radelet, Steven and Jeffrey Sachs. 2000. “The Onset of the East Asian Financial Crisis.” In Currency Crises. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8691.pdf.

Weissman, Jordan. 2016. “Bernie Sanders’ Bizarre Idea of Fair Trade.” Slate.com, April 5. http://www.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2016/04/05/bernie_sanders_is_the_developing_world_s_worst_nightmare.html.

Zakaria, Fareed. 2016. “Barack Obama is Now Alone in Washington.” Washington Post, September 1. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/barack-obama-is-now-alone-in-washington/2016/09/01/4d2e1348-7080-11e6-9705-23e51a2f424d_story.html.

[1] See also Baker (2016).

[2] Sovereign wealth funds that are invested in foreign assets have the same impact on currency values as reserve holdings by central banks.

[3] Part of this gap is due to the fact that roughly two-thirds of the doctors in the United States are specialists, whereas the average for other wealthy countries is close to one-third. However since these other countries have comparable medical outcomes, it does not appear we are benefitting from our increased use of specialists. If there was a large influx of foreign doctors presumably it would be possible to get around the doctors’ cartels that push the use of specialists in contexts in which they are not needed.

[4] The income tax on a foreign-trained professional’s wages would be an obvious reference point for the amount to be repatriated to their home country, but the actual sum could be either higher or lower.

[5] http://www.thebodypro.com/content/78658/1000-fold-mark-up-for-drug-prices-in-high-income-c.html

[6] This discussion draws extensively from Baker (2016, chapter 5).

[7] Katari and Baker (2015).

[8] In the case of companies competing for funding for biomedical research, there can be a rating system based on the past effectiveness of their research. In this case, $1 given to a highly rated company can count as $1 towards meeting its commitment. A payment of $1 to a less highly rated company may only count as 80 cents towards the commitment, and a $1 given to a poorly rated company may only count as 40 cents towards its commitment. This sort of mechanism should limit the extent to which cronyism could distort the flow of research funding.

[9] The subsidy is considerably larger for those in the highest tax bracket than for those in the middle and bottom of the distribution, most of whom do not even itemize deductions on their tax returns.