September 19, 2017

As we previously pointed out, the most disadvantaged segments of the labor market benefit disproportionately from low unemployment. This shows up both in terms of getting a disproportionate share of the job growth and also from seeing more rapid wage growth as a result of the tightening of the labor market they face.

The logic is straightforward. When the economy goes into a slump, it is more likely that a retail clerk or person on the factory floor will lose their job than a manager or a highly educated professional, like a doctor or dentist.

This means that when the unemployment rate soars, as it did in the Great Recession, it is the workers at the bottom of the ladder who are at greatest risk of losing their jobs. They are also the ones who see the largest loss in pay, as their bargaining power diminishes with their employment opportunities.

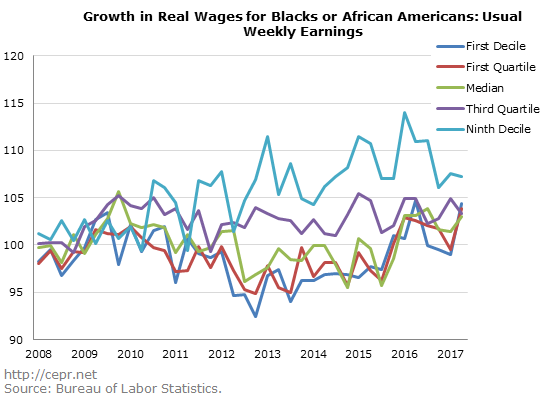

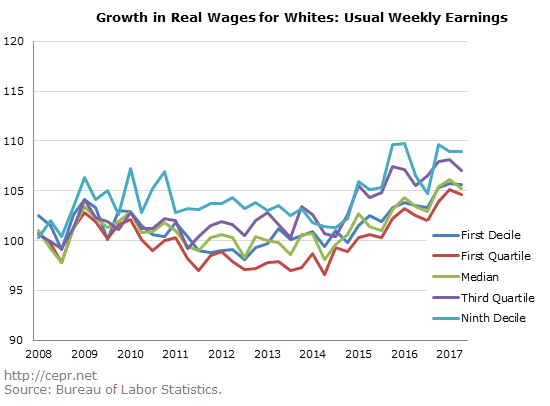

This post looks at the difference in patterns between blacks and whites. The graphs below shows real wage growth for full-time black and white workers since 2008 at the cutoff for the tenth and ninth deciles of wage distribution as well as the cutoffs for the first quartile, the median, and the third quartile. These data show usual weekly earnings. (The base is the year-round average for 2007.) The changes in this measure reflect both changes in average hours and also in hourly wages.

As can be seen, both black and white workers at the cutoff for the top decile of the wage distribution (the 90th percentile) did reasonably well through the Great Recession and the weak recovery that followed. (The data for black workers is more erratic due to the fact that the sample is smaller.) In fact, the 90th percentile black worker seems to have done somewhat better than the 90th percentile white worker in the recession and immediate aftermath. By 2012, when the unemployment rate still averaged 8.1 percent, their real wages were more than 5 percent higher than in 2007, whereas the gain for the 90th percentile white worker was roughly 4 percent. (It is important to remember that these are changes, the 90th percentile white worker earns far more than the 90th percentile black worker.)

Black workers at the cutoff for the third quartile (the 75th percentile) also appear to do have done slightly better than white workers at the same point along the wage distribution. Their wage gains are roughly a percentage point higher than for whites at the same point along the wage distribution.

However, the story reverses sharply when we look at the lower end of the wage distribution. Black workers at the cutoff for the first decline (10th percentile) and the first quartile (25th percentile) both saw real wage declines of close to 5 percent by 2012. For whites, the wage loss was in the range of 2–3 percent. This gap holds true at the median also, with the median black worker seeing a fall in real wages of close to 3 percent at a time when the median wages were roughly even with their 2008 level. This is consistent with the view that lower paid black workers are the biggest losers when the unemployment rate turns up.

The situation for lower paid black workers has improved substantially as the labor market has tightened in the last five years. Real weekly earnings for black workers at the cutoffs for the first decile and first quartile of the wage distribution, as well as the median, were 3.8 percent above their 2007 level in the most recent data. This still indicates a gap with whites at the same points of the distribution, who all saw gains in real wages of just over 5.0 percent. However, this indicates that the tightening of the labor market has disproportionately benefited blacks at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution.

By contrast, blacks at the top end of the wage distribution have fared less well. Real average weekly earnings for workers at the cutoff for the 9th decile were just 7.2 percent higher than their 2007 level in the most recent data, pretty much unchanged since the 2012 level. By contrast, wages for white workers at the cutoff for the 9th decile were 8.9 percent higher than their 2007 level.

This pattern suggests that wages for black workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution are far more sensitive to the unemployment rate than for white workers at the same point of the distribution. The implication is that if the labor market is allowed to continue to tighten, black workers at the middle and bottom of the wage distribution will see the largest wage gains. This is in addition to the fact that they are likely to also get a disproportionate share of employment gains.