November 06, 2015

Earlier this year, CEPR released a report titled From Recession to Collapse: The Bush Administration and the Over-Valued Dollar. The report shows that the strong value of the dollar during the Clinton-Bush years led to large trade deficits which decreased demand in the economy and resulted in lost jobs.

The economics on this point is pretty simple. A stronger dollar makes imports from other countries cheaper and makes U.S. exports more expensive. So when the dollar strengthens, American producers end up selling less merchandise, leading to job losses in sectors specializing in tradable goods.

However, some media outlets seem to view a strong dollar as a positive. Reporting on the dollar sometimes takes for granted that the term “strong” has a positive meaning and that the term “weak” conversely has a negative meaning.

This misconstruction has also been promulgated by various economists and policymakers. For example, in November 2010 a group of conservative economists (and Niall Ferguson) wrote an open letter to Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke warning about the dangers of “currency debasement and inflation.” Congressman Paul Ryan, the newly elected Speaker of the House, argued in 2010 that the Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing (QE) policy was “undermining the precepts of sound money.” He would later go on to criticize Bernanke in testimony before Congress, stating: “There is nothing more insidious that a country can do to its citizens than debase its currency.” But the misunderstanding was at least somewhat bipartisan, with then-Secretary of the Treasury Timothy Geithner stating, “[a] strong dollar will always be in the interest of the United States.”

Theory from even introductory economics courses says that these statements are wrong. Still, it’s been hard to clearly illustrate the jobs lost due to the strength of the dollar. CEPR has previously shown that a strong dollar has been associated with large trade deficits, and that those trade deficits are in turn associated with lost manufacturing jobs. However, even this analysis is imperfect, as there are a large number of factors affecting manufacturing employment besides just the strength of the dollar.

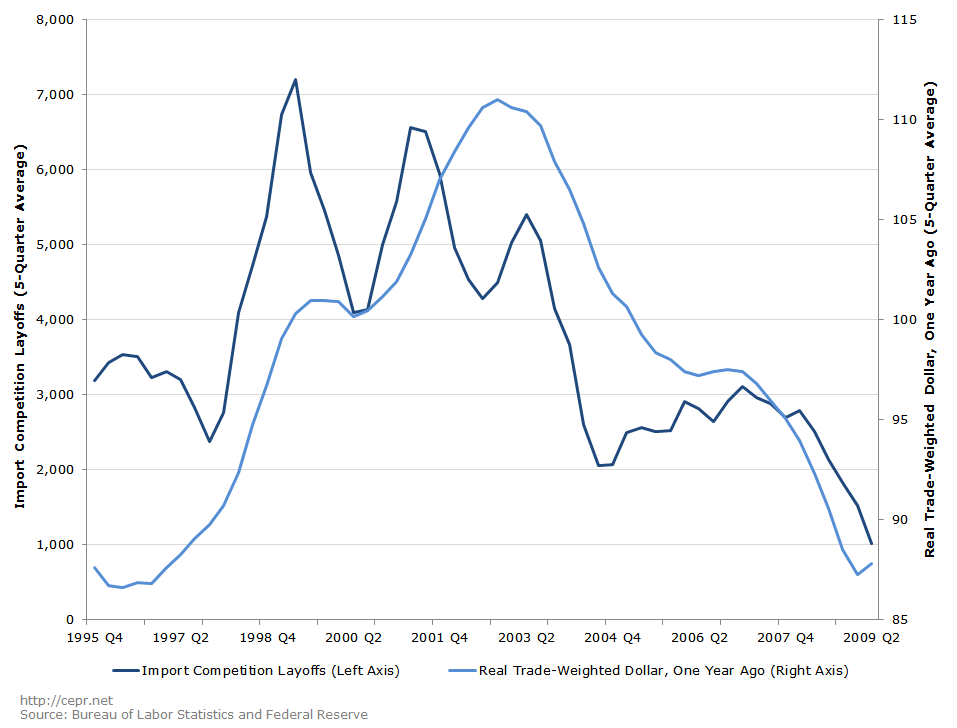

That’s why data provided by the Mass Layoff Statistics (MLS) program at the BLS is so helpful. The MLS program — which was eliminated due to budget sequestration, but still has its old data up online — tracked the number of jobs lost in “mass layoffs,” defined as layoffs of at least fifty workers over a period of five weeks. The MLS program was unique in that it directly asked employers why they were firing their workers, with one of the options being “Import Competition.” By comparing the MLS’ estimates of the jobs lost due to import competition with the value of the dollar, we can determine what effect, if any, the strength of the dollar has on job growth.

The graph below makes this comparison. The number of layoffs due to import competition is taken as a five-quarter moving average centered on the given value. (This means that the value for 1996 Q2 represents the average number of quarterly layoffs in 1995 Q4, 1996 Q1, 1996 Q2, 1996 Q3, and 1996 Q4.) Because a stronger dollar does not instantly result in layoffs (exports will gradually fall and imports will gradually increase, then some number of workers will be fired), the number of workers being fired due to import competition is compared with the value of the dollar from one year before. The values for the real trade-weighted dollar are taken from the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve, whose measure is indexed to 100 for March of 1973:

Basic economic theory gets this one right: a stronger dollar clearly leads to lost jobs. Despite what Paul Ryan, Timothy Geithner, and Niall Ferguson may tell you, a stronger dollar is not always in America’s interest.