October 27, 2020

Missed or late rent or mortgage payments with little confidence of being able to catch-up are hallmarks of what economists call “housing insecurity.” Black and Hispanic people are much more likely to be housing insecure than white people and have seen larger increases in housing insecurity during the pandemic. At the same time, there is considerable “hardship inequality” among white people. Hardship inequality is structured by education, income, and other factors. While housing insecurity has remained relatively stable among whites overall, it has spiked among lower-income whites (under $50,000) without college degrees.

Lower-income whites without college degrees were the largest group of voters who voted for Obama in 2012 but switched to Trump in 2016. The rise in material hardship among lower-income whites without college degrees, and the Congressional GOP’s opposition to new legislation addressing it, will likely make it harder for Trump to hold on to these important swing voters in the election.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Housing Insecurity Remain Large

In an August 2020 report, CEPR documented substantial racial and ethnic disparities in housing insecurity between late April 2020 and July 2020. Other research has documented similar racial disparities in COVID-19-related hospitalization and death, loss of earnings, food insecurity, and other hardships.

These disparities remain substantial. As Figure 1 shows, just over 40 percent of all white adults lived in a household where someone had lost employment income between March 2020 and August-September 2020. This is a very high number, but Black and Hispanic households were even harder hit, with about 52 percent of Black households and nearly 58 percent of Hispanic households experiencing earnings losses.

Fewer households have experienced housing insecurity than lost earnings, but the racial and ethnic disparities are even larger. In August-September 2020, Hispanic renters were almost twice as likely as white ones to be behind on rent, while Black renters were more than twice as likely as white ones to be behind on rent. Black homeowners were 2.5 times as likely as white ones to be behind on mortgage payments, and Hispanic homeowners were twice as likely to be behind on mortgage payments.

Housing Insecurity Differences Among Whites Before and During the Pandemic

White people have benefitted from structural and institutional racism for generations in the United States, yet there is still considerable economic and social stratification among white people, including by class, education, and income. This stratification means that lower-income, white people without two- or four-year college degrees are more likely to experience material and social hardships than other white people, particularly during economic downturns.

The figures below document differences in one of these hardships, housing insecurity, among white people. Figure 2 shows the recent trend in the percentage of white adults who report experiencing housing insecurity. Before 2020, the share of white people experiencing housing insecurity was relatively stable and there were not large differences between whites overall and lower-income whites without college degrees. However, the share of lower-income whites without college degrees reporting housing insecurity spiked in 2020. In August-September 2020, among lower-income whites without a college degree, about one-in-four renters were unsure if they would be able to pay next month’s rent. Among lower-income white homeowners without a college degree, housing insecurity increased by over 60 percent from 2019 to 2020. By contrast, it has remained relatively stable, or even declined, among white homeowners overall.

Figure 3 shows the differences in housing insecurity among white people in August-September 2020, by educational attainment. White renters without college degrees were more than twice as likely as those with college degrees to be housing insecure last month. The disparity is similar for white homeowners.

Working-class whites are often defined as whites who have not attended college or do not have a post-secondary credential. However, a substantial share of whites without college degrees have high incomes and occupations that are not typically associated with being “working-class.” Similarly, CEPR’s analysis of the General Social Survey shows that in recent years, about 34 percent of whites who have not attended college self-identified as “middle-class” or “upper-class” (rather than “lower-class” or “working-class”), compared to only about 25 percent of Blacks and Hispanics in this same educational group.

Figure 4 shows how these differences in occupations and income translate into differences in housing insecurity. Among all whites without college degrees, whites with incomes below $50,000 are more than twice as likely to be housing insecure as those with incomes above $100,000. Figure 4 also presents differences in the likelihood of eviction or foreclosure. Among whites without a college degree, 8.2 percent of lower-income renters believe it is very likely or somewhat likely that they could be evicted in the next two months, compared to only 1.2 percent of all of high-income renters.

Implications for 2020 Presidential Election

Among white people without college degrees, political leanings differ considerably based on income. Higher-income whites without college degrees have been an established, unwavering part of the Republican base for decades. They tend to support conservative economic policies and oppose progressive economic policies. By contrast, lower-income whites without college degrees are more supportive of progressive economic policies. As a result, even though they have been trending away from Democrats and toward Republicans over time, they remain a major swing-voter group.

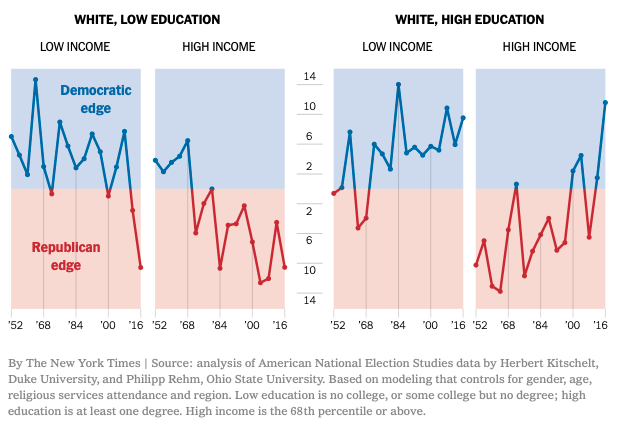

These trends are documented in recent research by political scientists Herbert Kitschelt and Philip Rehm. The figure below, from a 2019 New York Times article discussing Kitschelt and Rehm’s research, shows trends of how whites have voted in Presidential elections since 1952, by education and income. As seen in the left-most line graph, white low-income voters without college degrees swung to Obama in 2008 and then sharply to Trump in 2016.

Trends in White Presidential Vote by Education and Income, 1952-2016

(reproduced from New York Times)

Source: Thomas Edsall, We Aren’t Seeing White Support for Trump for What It Is, New York Times, August 28, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/28/opinion/trump-white-voters.html.

The vast majority of white voters did not switch parties between 2012 and 2016: 47.6 percent were Romney-Trump voters and another 40.8 percent were Obama-Clinton voters. However, among the 11.6 percent of white voters who did switch parties, the largest group of vote switchers were lower-income whites without college degrees who switched from Obama to Trump. This group accounted for 4.8 percent of all white voters in 2016, and 41 percent of all white vote switchers. Kitschelt and Rehm attribute this result to cultural concerns becoming more salient in 2016 to lower-income whites without college degrees and their perception that Trump was less conservative on economic issues than prior, more conventional Republican presidential candidates.

If not for the pandemic and the resulting economic crisis, Trump may have been able to hold on to his gains among lower-income whites without college degrees. But the spike in housing insecurity — and probably other forms of economic hardship not examined in this paper — experienced by lower-income whites without college degrees makes retaining all of these vote switchers more difficult for him.

Concern about losing too many white swing voters who have been hammered by the downturn may explain why Trump has urged the Congressional GOP to “go big or go home” on coronavirus relief and his claim that he wants a package that is “even bigger than the Democrats.” At the same time, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell’s opposition to a deal, and prioritization of confirming conservative Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court, likely undermines Trump’s reelection bid.

Politics aside, if members of Congress want to reduce the economic hardships of America’s diverse working-class, they should support the House-passed HEROES Act, which includes provisions that boost unemployment insurance by $600 a week, extend the federal eviction moratorium for 12 months, and provides $71 billion in emergency assistance to renters and homeowners.

In short, with growing bipartisan disapproval of the way the administration is handling COVID-19, along with the Senate hindering progress for a stimulus bill that would help millions of working-class Democrats and Republicans alike, it seems increasingly likely that a substantial portion of white, working-class Obama-to-Trump vote switchers will become Trump-to-Biden vote switchers in 2020.

Methodology

The data on housing insecurity for 2020 are from weeks 13 and 14 of the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey (HPS) and cover August 19, 2020 to September 14, 2020. Three survey questions in the Census HPS measure housing insecurity: (a) whether the household is currently caught up on rent or mortgage payments; (b) how confident respondents are that their household will be able to pay its next housing payment on time; and (c) for households that are not caught up on rent or mortgage payments, how likely it is that the household will have to leave its current home or apartment within the next two months due to eviction or foreclosure.

The listed answers for the second question are: no/slight/moderate/high confidence and payment is or will be deferred. We categorize answers to the second question as a dichotomous variable and define households as lacking confidence about upcoming payments if they reported no or slight confidence or if they anticipated deferring, or had already deferred, next month’s payment. The listed answers for the third question are: very/somewhat/not very/not likely at all. We define a household as being likely to experience displacement in the following two months if they reported “very or somewhat likely.”

The data on housing insecurity from 2017 to 2019 come from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED). The specific question asked in the SHED is “Are you expecting to be unable to pay or only make a partial payment on each of the following bills this month?” with “rent or mortgage” being one of the listed bills.

Following Kitschelt and Rehm, people without college degrees are defined as people without an A.A. degree, a B.A. degree or any other higher degree, and includes people who may have “some college” but no degree.

Finally, it is important to note that, if anything, the housing figures reported may underestimate the share of adults who were housing insecure. The housing questions in the Census Household Pulse Survey come near the end of the survey, and a substantial number of respondents did not answer them. Respondents who did not answer any or all of the survey likely have lower levels of educational attainment and employment than respondents who did answer them, and, thus may be more likely to be housing insecure.