September 29, 2012

It is remarkable how people keep insisting, in spite of all the evidence to the contrary, that the problem of the downturn is a financial crisis rather than simply a collapsed housing bubble. The latter story is simple. Housing construction was driven by bubble-inflated prices. When prices plunged, construction collapsed. Not only did we no longer have inflated prices to drive construction, we also had an enormous oversupply as a result of 5 years of near record rates of construction. From 2006 to 2009 construction fell by more than 4 percentage points of GDP, leading to a loss of more than $600 billion in annual demand.

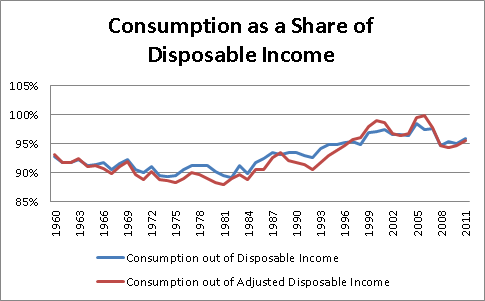

In addition, the loss of $8 trillion in housing wealth lead to sharp falloff in consumption. While the housing wealth effect is a long-established and widely accepted economic phenomenon, most discussions of the financial crisis act as though this effect does not exist. The wealth created by the run-up in house prices led to a consumption boom as the saving rate fell to near zero. With the collapse of the bubble, consumption fell back as the wealth that has been driving it disappeared.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

However, contrary to what is widely asserted, for example by David Leonhardt in his column today, consumption remains high, not low. The saving rate averaged more than 8.0 percent of disposable income in the years prior to the rise of the stock bubble in the 90s. Currently, it is between 4 and 5 percent of disposable income. If anything, we should be asking why consumption is so high, not why it is low.

It would be too absurd to expect bubble levels of consumption in the absence of the bubble. However this is what proponents of the financial crisis theory seem to be arguing. In short, the collapse of the bubble led to a gap of more than $1 trillion in lost demand due to the plunge in construction and the falloff in consumption. What if any part of this requires a story about the financial crisis?

Comments