March 31, 2016

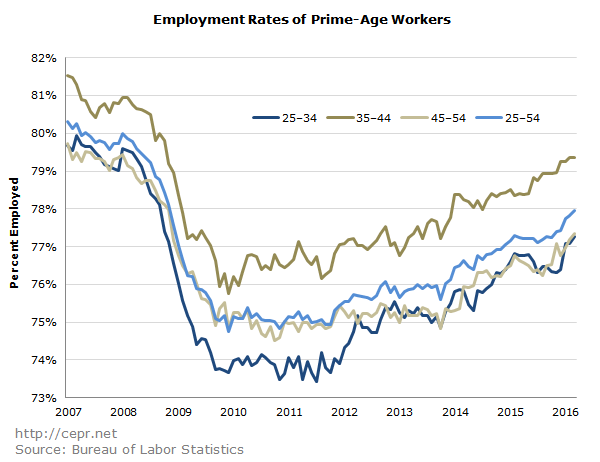

The graph above displays the change in the prime-age employment rate for twenty countries between 2007 and 2015. Included in the graph are the United States, the remaining G-7 countries, various other advanced economies, and Mexico. (Mexico and Canada provide a useful point of comparison with the United States since they are part of the same regional economy.)

The prime-age employment rate is a far better gauge of the labor market than the unemployment rate. As such, the graph above is useful in determining the level of employment lost in each country as a result of the 2008 recession.

There are three important takeaways from the graph. First, most advanced countries have yet to fully recover from the recession. Of the twenty countries depicted in the graph, thirteen had a lower prime-age employment rate in 2015 than in 2007. Last year, eight of the countries had prime-age employment rates that were at least two percentage points lower than their 2007 employment rates. This serves as evidence of significant, widespread job loss in a number of developed countries.

Second, countries which followed different policy regimes had strikingly different results. The most obvious result is the tremendously negative effects of staying on the Euro, which deprives countries of monetary policy independence. Of the eight countries on the Euro, seven experienced drops in employment between 2007 and 2015; moreover, all five of the nations with the largest employment drops are on the Euro. By contrast, amongst the twelve countries with independent national currencies, only six saw a drop in employment; and even then, four of the six countries saw decreases of less than one percentage point. The experiences of countries on the Euro have been far worse than the experiences of countries with their own currencies.

Another visible result is the negative effects of austerity. Greece, Spain, Italy, and Ireland — the four countries with the biggest drops in prime-age employment — have put in place very harsh austerity measures. By contrast, Japan — a country which has been harangued by deficit scaremongers for its recent stimulus measures — has seen a 2.0 percentage-point increase in its prime-age employment rate. The experiences of countries imposing austerity and those pursuing stimulus could not be more divergent.

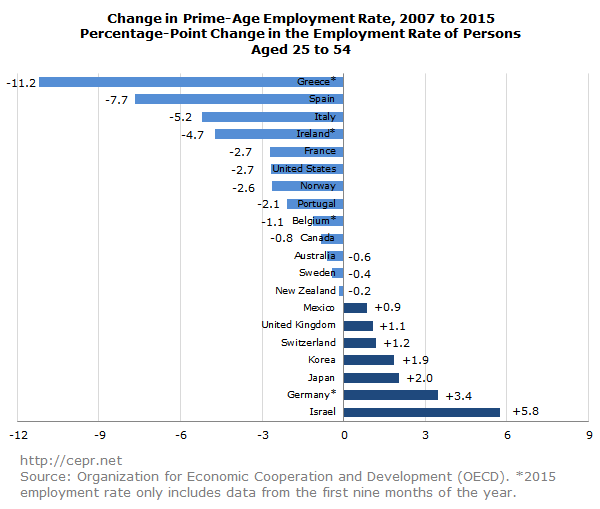

Finally, there is a third takeaway for those who are interested in the U.S. specifically. Public perception aside, the U.S. has actually engaged in a fair bit of fiscal austerity over the past few years, though monetary policy (most notably through quantitative easing and low interest rates) has been pushing in the opposite direction. Not surprisingly, the U.S. is on the more negative side of the employment changes. Only five of the other nineteen countries have experienced greater drops in prime-age employment than the U.S., and those five countries are all on the Euro. America’s neighbors have fared better than us, with Canada experiencing a prime-age employment drop of 0.8 percentage points and Mexico experiencing an increase of 0.9 percentage points. In the U.S., prime-age employment fell by 2.7 percentage points between 2007 and 2015. Granted, the beginning of 2016 has been positive, with the prime-age employment rate having increased a little over 0.5 percentage points since December of last year. But be that as it may, the prime-age employment rate is still down 2.0 percentage points since 2007. As displayed in the figure below, employment is down by 2.2 percentage points for 25–34 year-olds, 1.5 percentage points for 35–44 year-olds, and 2.0 percentage points for 45–54 year-olds, indicating that employment is down all along the age distribution for Americans whom we’d typically expect to be working.