February 15, 2012

February 15, 2012

John Schmitt on Testimony Before the House Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade on “Where the Jobs Are: Employment Trends and Analysis”

Good morning Chairwoman Bono Mack, Ranking Member Butterfield, and Members of the Subcommittee. Thank you for inviting me to testify this morning. My name is John Schmitt. I am a Senior Economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) here in Washington, DC, where I specialize in labor-market issues.

The labor market is in a stronger position now than at any time in the last four years. The private sector has been creating jobs, on net, for the last 23 months –a total of about 3.5 million jobs since March 2010 (Figure 1). The unemployment rate is down to 8.3 percent, from its October 2009 peak of 10.0 percent (Figure 2).

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 played an important role in righting the economy after the crash in the housing bubble triggered a recession and a full-scale financial panic. According to estimates by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the ARRA was responsible for saving or creating between 1.3 and 3.3 million jobs in 2010 and 900,000 and 2.7 million jobs in 2011. This year, even as ARRA spending phases out, the CBO projects that the ARRA will increase employment by 400,000 to 1.1 million jobs.[1] Subsequent federal measures, including the extension of unemployment insurance and the temporary reduction in the payroll tax, have also had a positive effect on job creation by sustaining flagging consumer demand. As many economists said at the time that the ARRA was passed, the biggest problem with the bill was that it was not big enough to address the depth of the jobs crisis facing the country.

Simple extrapolations of recent trends serve to put these recent developments into some perspective. If overall job growth continues at about 200,000 jobs per month, which is the average over the last three months, the economy will have two million more jobs in November than we have today. And if the unemployment rate continues to fall at the pace that it has since August 2011 –a decline of 0.8 percentage points in five months– the national unemployment rate, which currently stands at 8.3 percent would hit 6.7 percent by November. Of course, simple extrapolations are not careful forecasts, and more formal analysis, including those made by Council of Economic Advisers, put the unemployment rate at the end of this year in the range of 8 percent.[2]

Despite some encouraging data over the past few months, the labor market is, by no means, out of the woods. During the 23 months that the private sector has been creating jobs, budget cuts have forced state-and-local governments to reduce employment by almost half a million (Figure 3). These figures don’t capture the full impact of austerity at the state-and-local level, however, because they don’t include related losses in the private-sector firms, many of them small businesses, that provide goods and services to state-and-local governments.

The recent acceleration in job creation is welcome, but slow by any reasonable benchmark. We still have about 5.5 million fewer jobs today than we did in December 2007, when the recession began. At the average rate of job creation achieved over the last three months, it would still take more than two years to get back to where we were before the recession got underway. But, the task is even more daunting because each month, demographic forces increase the size of the labor force by at least 90,000 new, potential workers (and some analysts suggest the figure is even higher). If we factor in the growth in the labor force since December 2007, the jobs deficit isn’t 5.5 million jobs, but about 10 million (and growing by about one million jobs per year). At the current pace, closing the gap on this moving target would take over seven years; this means a return to the unemployment rate we had in 2007 would not occur until 2019.

While unemployment has fallen in recent months, by historical standards, it remains high. In the entire postwar period, excluding the current downturn, only three years had an annual unemployment rate above the current 8.3 percent level. At no time in the postwar period has the unemployment rate been this high more than two and a half years into an economic recovery.

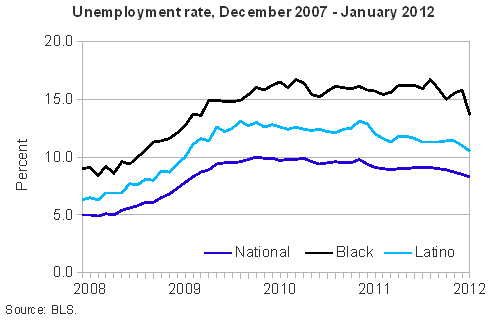

Unemployment rates are particularly elevated for the quarter of our adult population that is African American or Latino (Figure 4). Rates for these two groups have always been higher than the overall average, but even as the national unemployment rate has fallen to 8.3 percent, the rate for black workers is almost 14 percent and the rate for Latino workers remains above 10 percent.

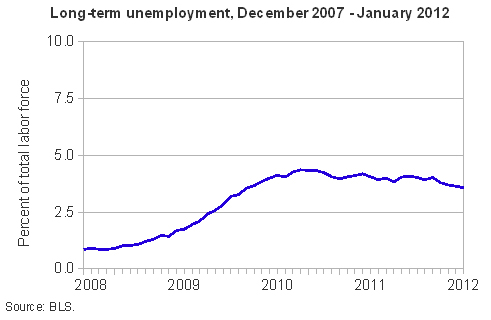

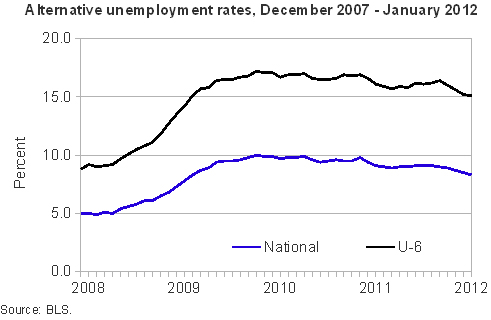

Another area of significant concern are the stubbornly high rates of long-term unemployment and long-term hardship in the labor market. The share of the labor force that has been unemployed for six months or longer is still above where it was at the low point of the Great Recession in July 2009 and almost as high as the overall unemployment in 2007 (Figure 5). The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) expanded unemployment measure known as U-6 remains above 15 percent, almost double the official unemployment rate (Figure 6). This measure augments the standard unemployment rate by adding “discouraged workers” and others who would like to work but currently don’t, as well as those who are working part-time but want full-time work. Many of these workers or potential workers have been in these difficult circumstances for long periods, but are not counted in the official measure of long-term unemployment. According to estimates that my colleague, Janelle Jones, and I recently produced, the share of people experiencing “long-term hardship” in the labor market is likely to be at least twice as large as the share that meet the official definition of long-term unemployment.[3]

Job creation is the most pressing problem facing economic policymakers today. What can we do to get the economy back to full employment? And what factors are holding us back?

Let me begin to answer these questions by being clear about what is not holding us back. So-called “structural” problems in the labor market have played little or no role in the huge increase in unemployment since 2007.

Sustained, high unemployment over several years has led some economic analysts to suggest that “structural” problems in the labor market are the biggest barrier to getting the economy back on track. The two most common structural barriers mentioned are the unemployment insurance system and an alleged mismatch between the skills workers have and the skills employers need. Neither of these concerns stands up to close scrutiny.

The best evidence on the direct impact of the unemployment insurance system shows that it increases the average duration of unemployment by a relatively short period –on the order of a few weeks– and, as a result, increases the overall unemployment rate by a small amount –on the order of a few tenths of a percentage point.[4] A recent analysis by Berkeley economist Jesse Rothstein, for example, concluded that extensions of unemployment insurance benefits during the Great Recession raised the overall unemployment rate by between 0.2 and 0.6 percentage points (relative to a total increase in the unemployment rate of 5.0 percentage points from December 2007 level to its peak in 2010).[5] Rothstein’s estimates suggest that half or more of this 0.2 to 0.6 percentage-point rise was the result of reduced labor-force exit –that is, receiving unemployment insurance encouraged workers, who otherwise would have given up looking, to stick with their job search.[6] The increase in unemployment associated with workers being pickier about the jobs they eventually take was, in Rothstein’s calculations, only between 0.1 and 0.3 percentage points.

These minimal direct impacts of unemployment insurance on the behavior of the unemployed, however, are only part of the story. Unemployment benefits also inject income into families and communities experiencing sudden, sharp declines in purchasing power. Because the unemployed are usually cash-constrained, benefits paid to them quickly make their way into the economy in the form of rent, car payments, groceries, and other necessities. At the end of last year, Economists Lawrence Mishel and Heidi Shierholz of the Economic Policy Institute estimated that a $45 billion extension in unemployment insurance benefits would, thanks to a high associated multiplier effect, increase the GDP this year by $72 billion, or roughly a half million additional jobs.[7] The impact of this direct cash infusion swamps the behavioral responses of unemployed workers receiving benefits.

“Skills mismatch” is not a serious structural barrier to more rapid job growth either. Proponents of this view argue that employers are eager to expand output, but are currently constrained by the lack of workers with available skills. Media accounts occasionally feature employers who say that they want to expand their operations, but can’t find the kind of workers they need. But, even the best functioning economy will always have some employers, particularly the most innovative ones, that are looking for particular kinds of workers that are in short supply in that moment. This holds in the same way that there were some employers still hiring in the depths of the recession and some employers laying-off workers even at the peak of the last boom. To assess whether the economy is facing a structural mismatch, however, we must go beyond anecdotes. The available statistical evidence provides little support for the idea that the anecdotal experiences of employers facing skills shortages are widespread, let alone typical.

The strongest argument against the existence of a skills shortage is what were are not seeing in labor market data. If skilled workers were in short supply, we would expect so see two things. The first is an increase in the hours worked by existing workers, who are likely to have some or all of the skills employers are looking for precisely because employers hired them in the first place. In fact, average hours worked have not risen substantially over the recovery and are still below their pre-recession level.

The second thing we would expect if we were facing a skills shortage is that employers would be raising wages to attract the kinds of workers they need. This is basic economics. When something is in short supply, its price goes up. But, again, we see no signs of upward movements in the wages for any broad group of workers. As just one example, after rising steadily in the 1980s and 1990s, the gap between what college-educated and high school educated workers earn has been flat for a decade.

One standard framing of the skills mismatch view also flies in the face of common sense. As economist Heather Boushey of the Center for American Progress testified before this committee last year:

“In May 2007, the unemployment rate was 4.5 percent. Just more than a year and a half

later, the private sector was shedding 700,000 to 800,000 jobs per month… For the unemployment problem to be structural, it would have to be the case that our nation’s workers and employers all of a sudden became mismatched due to some new set of technological advances that made 1 in 10 workers instantaneously obsolete.”[8] [My emphasis.]

If structural problems in the labor market are not to blame for continued high unemployment,[9] what is? The answer here is clear: a lack of demand. The economy is currently operating substantially below the limits set by the capital stock –factories, machinery, offices, software, equipment– and the available labor supply. The binding constraint is not the productive capacity of the economy, but rather the demand for the goods and services that the economy is already completely capable of producing.

The sharp drop in demand has its roots in the collapse of the housing bubble in 2006, which devastated the construction sector and wiped out an important part of the wealth holdings of middle-class homeowners. As the housing bubble was inflating, Americans used their homes to top up their stagnating wages and slow-growing incomes. When the bubble burst –at the cost of $6 trillion dollars in housing wealth– the process ran in reverse, with families cutting back on expenses to try to cover their losses. My CEPR colleague, Dean Baker, estimates that the decline in household consumption related to the drop in household wealth totals about 3 to 4 percent of GDP per year. This decline in spending set off a chain reaction.[10] Lower household spending led to lower incomes for other households, which led to additional cuts in spending. Firms, seeing their customers disappear, cut back on investment, further reducing demand in the economy. The financial crisis in 2008, which followed the bursting of the housing bubble and the onset of the recession, reinforced this downward spiral.

The ARRA, while far too modest in size, was an important step in helping to break this negative cycle. What the economy needs now is continued efforts to sustain and restore demand. With the unemployment rate still far above full employment, government deficits are an important tool for getting the economy back on course. A large-scale jobs program would be ideal, but, short of that, several measures would go a long way to help.

- First, a further extension of unemployment insurance benefits would get incomes into the hands of a group that will spend those funds supporting the broader economy.

- Second, while less efficient as a jobs creator, an extension of the payroll tax cut would also help to support demand until the private sector is fully back on its feet.

- Third, increased federal support for state-and-local governments would help them to restore some or all of the almost half a million public-sector jobs lost in the last two years, not to mention the private-sector jobs built around supporting vital state-and-local government activities.

- Finally, at no cost to the U.S. Treasury, economic policymakers could act to restore the U.S. dollar to a more competitive level. A more sensible value for the dollar would dramatically improve the competitiveness of U.S. manufactured goods in export markets and here at home. In the long-run, a more competitive dollar could add five million manufacturing jobs to the economy.[11]

One additional policy that would help the employment picture regardless of the state of aggregate demand is “work-sharing.” Work-sharing would allow employers facing the need for layoffs to cut the average hours of their workforce rather than the total number of workers —with workers receiving partial unemployment benefits to compensate for part of their reduced income. The policy enjoys support across the political spectrum –from my colleague, Dean Baker, to American Enterprise Institute economist Kevin Hassett.[12] Work-sharing systems are currently in place in about 20 states, but for a variety of program-design reasons are only infrequently used.[13] Work-sharing does not directly address the problem of aggregate demand, but it would much more equitably share the burden of unemployment; and because employers are able to retain their existing staff, work-sharing can leave the economy better positioned for growth when consumer and investment demand do eventually return. A similar “part-time unemployment benefit” system in Germany is one reason why the unemployment rate there is actually lower today than it was before the Great Recession began.[14]

The labor market is looking brighter now than at any point in years. But, enormous challenges remain. The problems we face today are the result of a collapse in consumer and investment demand that derailed an economy that had been operating much closer to full employment. The way forward requires measures that will sustain and spur private-sector demand, including extended unemployment insurance benefits, a continuation of the payroll tax cut, renewed support for state-and-local governments, and a move toward a more competitive U.S. dollar.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

[1] Congressional Budget Office, “Estimated Impact of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on Employment and Economic Output from April 2011 Through June 2011,” Table 1. http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/123xx/doc12385/08-24-ARRA.pdf.

[2] Jackie Calmes, “Obama Advisers Offer Rosier Jobs Outlook,” New York Times, February 9, 2012, p. B9.

[3] John Schmitt and Janelle Jones, “Down and Out: Measuring Long-term Hardship in the Labor Market,” Center for Economic and Policy Research Briefing Paper, January 2012. /documents/publications/unemployment-2012-01.pdf

[4] For recent research on the impact of unemployment insurance on unemployment duration and the unemployment rate, see Rob Valetta and Katherine Kuang, “Extended Unemployment and UI Benefits,” FRBSF Economic Letters, April 19, 2010, http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/letter/2010/el2010-12.html; David Card, Raj Chetty, and Andrea Weber, “The spike at benefit exhaustion: leaving the unemployment system or starting a new job?”

[5] Jesse Rothstein, “Unemployment Insurance and Job Search in the Great Recession,” National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper No. 17534, October 2011.

[6] Unemployment insurance can lead people to continue to look for work because an active job search is a condition of receiving benefits.

[7] Lawrence Mishel and Heidi Shierholz,”Labor market will lose over half a million jobs if UI extensions expire in 2012,” Economic Policy Institute Issue Brief #318, November 4, 2011, http://www.epi.org/publication/labor-market-lose-million-jobs-ui-extensions/

[8] Heather Boushey, “Testimony Before the House Committee on Energy and Commerce, Subcommittee on Commerce, Manufacturing, and Trade,” March 3, 2011, http://democrats.energycommerce.house.gov/sites/default/files/image_uploads/Boushey.Testimony%202011-3-3.pdf

[9] For recent studies from Federal Reserve and International Monetary Fund economists that find only small increases in structural unemployment during the Great Recession, see: Mary Daly, Bart Hobijn, and Rob Valletta, “The Recent Evolution of the Natural Rate of Unemployment,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2010, http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/papers/2011/wp11-05bk.pdf; Justin Weidner and John C. Williams, “What is the New Normal Unemployment Rate?” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter, February 14, 2011, http://www.frbsf.org/publications/economics/letter/2011/el2011-05.html; Regis Barnichon and Andrew Figura, “What Drives Movements in the Unemployment Rate? A Decomposition of the Beveridge Curve,” Federal Reserve Board, Finance and Economics Discussion Paper 2010-48, 2010, http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2010/ 201048/201048pap.pdf; Aysegul Sahin, Joseph Song, Giorgio Topa, and Giovanni L. Violante, “Measuring Mismatch in the U.S. Labor Market,” New York Federal Reserve, October 2011, http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/ economists/sahin/USmismatch.pdf; Jinzhu Chen, Prakash Kannan, Prakash Loungani and Bharat Trehan, “New Evidence on Cyclical and Structural Sources of Unemployment,” International Monetary Fund Working Paper No. 11/106, May 2011, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2011/wp11106.pdf.

[10] Dean Baker, The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive, Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, 2011, Chapter 2. https://www.cepr.net/index.php/publications/books/the-end-of-loser-liberalism. Baker also estimates that the collapse in residential construction initially reduced GDP another 4 percent, further fueling the effects described here.

[11] Dean Baker, “The Necessity of a Lower Dollar and the Route There,” Center for Economic and Policy Research Briefing Paper, February 2012, /documents/publications/lower-dollar-2012-02.pdf.

[12] See, for example, Dean Baker and Kevin Hassett, “Work-sharing could work for us,” Los Angeles Times, , April 5, 2010, http://articles.latimes.com/2010/apr/05/opinion/la-oe-baker5-2010apr05; and Kevin A. Hassett, “U.S. Should Try Germany’s Unemployment Medicine,” Bloomberg.com, November 9, 2009, http://www.aei.org/article/economics/fiscal-policy/us-should-try-germanys-unemployment-medicine/.

[13] See Wayne Vroman and Vera Brusentev, “Short-Time Compensation as a Policy to Stabilize Employment,” The Urban Institute, November 2009, http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/411983_stabilize_employment.pdf.

[14] John Schmitt, “Labor Market Policy in the Great Recession: Some Lessons from Denmark and Germany,” Center for Economic and Policy Research Briefing Paper, May 2011, /documents/publications/labor-2011-05.pdf.