March 29, 2013

In both her story on disability insurance and a Wonkblog interview, reporter Chana Joffe-Walt implies that lots of people are receiving Supplemental Security who don’t deserve the help, and that large numbers of families with children have simply been shifted from Temporary Assistance to Supplemental Security. I was just sitting down to write on why Joffe-Walt’s treatment of this issue is so misleading, when I noticed that Harold Pollack, a disability expert and professor at the University of Chicago, beat me to it in this terrific blog post. (Wonkblog also has an interview with Pollack discussing this and other problematic aspects of the story.)

Some key points made by Pollack:

- “Child SSI caseloads are not exploding. Nor are large numbers of single moms transitioning from traditional welfare (Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, or TANF) to SSI. … Rising poverty rates, not lax program rules, is the critical factor.”

- “[T]he rise in the child SSI caseloads is dwarfed by the decline in the number of children receiving cash assistance after the 1996 welfare reform.”

- “Child SSI is simply a small matter when shown alongside one of the tragic policy failures of the Great Recession: TANF’s failure to remotely keep pace with macroeconomic crisis and rising child poverty.” Here Pollack points to a graph showing that the percentage of children below the poverty line receiving either Temporary Assistance or Supplemental Security has fallen by more than half since the mid-1990s.

- Two graphs juxtaposed by Joffe-Walt—one showing the decline in the number of families with children receiving Temporary Assistance and the other showing an increase in the number of low-income adults generally receiving Supplemental Security—“just don’t go together. They cover different populations, whose dynamics are influenced by different processes.”

- Pollack points to a longitudinal study that tracked particularly disadvantaged single parents receiving Temporary Assistance between 1997 and 2003: “By the end of the survey period, 37 out of 532 women ended up on SSI or SSDI. 114 others had applied for disability benefits, but were found ineligible within a supposedly lax disability system.”

A few points of my own to add to this.

Joffe-Walt says in her Wonkblog interview that “welfare reform [specifically the 1996 law that converted AFDC into the Temporary Assistance block grant] … gave states an incentive to move people who they couldn’t get into jobs into disability programs.” But this was also true of state incentives under AFDC before 1996, since states had to provide matching funds and were subject to a federal obligation to help all eligible low-income families. Under Temporary Assistance, there is no federal obligation to help all eligible families and the state match has been replaced by a loose requirement to show that the state is spending as much in nominal dollars on an extremely wide range of social services and benefits as it did on AFDC in the early 1990s.

The core incentive problem with Temporary Assistance isn’t that it gave states some new incentive to shift parents and children to disability programs, it’s that it gave states a huge new incentive to not help parents and children at all in meaningful ways, without providing any mechanism to counter this new, adverse incentive. The fundamental incentive problem here is similar to that presented when insurance companies are able to deny coverage to people with preexisting conditions.

If there had been a big shift from Temporary Assistance to disability benefits, we’d expect to have seen particularly elevated growth in the receipt of Supplemental Security by women (since adults receiving AFDC/TANF are almost all single mothers). But there doesn’t appear to have been any big shift in the gender ratio of Supplemental Security beneficiaries (in 1999, 56 percent of non-elderly adult beneficiaries were women; in 2011, it was 54 percent).

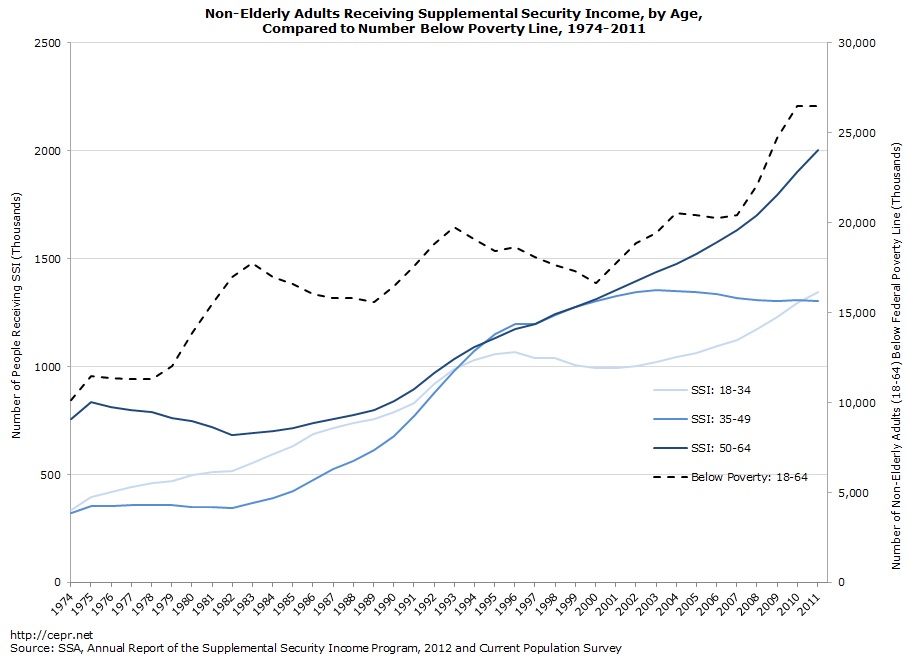

Click for a larger version

We’d also expect to have seen the greatest growth among younger adult cohorts, since roughly half of mothers receiving AFDC/TANF are under age 30 and very few are over age 50. The chart above compares the increase in the number of non-elderly adults living below the poverty line (the dotted line with the numbers on the right axis) with the number of non-elderly adults receiving SSI by age group (the other three lines with numbers on the left axis). As it shows, most of the growth in SSI happened among people age 50-64, while the trend is flat for those between 35-49. There’s an uptick for the 18-34 age group since the start of the recession, but it is less steep than the increase in adult poverty and not much different than the increase during the Reagan-Bush I years.

So for both Supplemental Security and Disability Insurance, as Pollack and my colleague Dean Baker point out, the real story is about the combination of an aging population and an economy down 9 million jobs from its growth path that isn’t providing sufficient opportunities for workers. The massive jobs gap is particularly harmful for people with disabilities, who have a tough time finding work they can do even when times are good. If we had 7 million more jobs, people with disabilities would have a much better shot at finding work they could do despite their functional limitations, and fewer of them would need to turn to disability insurance.