March 27, 2013

As my colleague Dean Baker has noted, a controversial This American Life piece on disability insurance “got some of the basics wrong” and “failed to recognize the actual importance of the economic collapse.” Yet, in a statement to the press, Ira Glass says he knows of “no factual errors” in the story on disability and stands by it.

I won’t take on the entire story here, but I want to note one quite clear-cut and basic factual error. In the story, reporter Chana Joffe-Walt unequivocally states: “People on federal disability do not work.” This is factually incorrect. According to researchers at Mathematica and SSA, about 17 percent of disability beneficiaries worked in 2007. Their earnings were generally very low (about 4.8 percent had annual earnings of $1,000 or less), but that doesn’t justify the reporter’s unequivocal characterization of all disability beneficiaries as non-workers.

A related technical error in the story, Joffe-Walt goes on to say: “Yet because [disability beneficiaries] are not technically part of the labor force, they are not counted among the unemployed.” For unemployment rate purposes, the Bureau of Labor Statistics counts people as unemployed if they have no employment, were available for work, except for temporary illness, and made specific efforts to find employment during the last four weeks. So, while the vast majority of disability beneficiaries are not counted in the unemployment rate, that’s different than saying absolutely none of them are counted.

BLS has published regular data on the employment and unemployment status of people with disabilities since 2009. In February 2013, the unemployment rate for people with disabilities (those in the labor force looking for work, most of whom probably do not receive disability benefits) was considerably higher (12.3 percent) than the rate for people with no disability (7.9 percent). This disparity, which should get much more attention than it currently does, was not mentioned at all in the story. This is especially striking because, as Stephan Lefebvre, a research assistant at CEPR, reminded me, equal employment opportunity has been such a major focus of disability activists in recent decades.

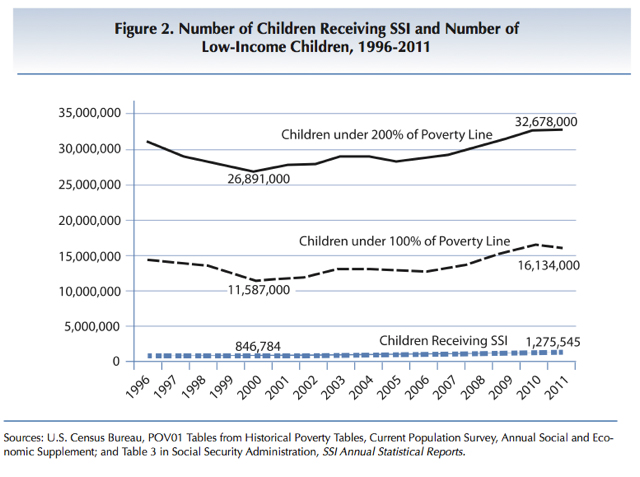

Finally, Glass takes issue with an analysis that I did with Rebecca Vallas, one cited by Media Matters, showing that the recent rise in the number of children with severe disabilities receiving Supplemental Security benefits is largely due to economic factors. Glass says: “They [Media Matters] choose data from 2000-2009 to back up that claim…. As we point out in our reporting, when you look at a longer period of time—at 30 years of economic data—you see a different story.”

But neither Glass nor Joffe-Walt say what that “different story” actually is. Vallas and I have focused—for example in this paper for the National Academy of Social Insurance —on the trends over roughly the last 15 years because Supplemental Security’s eligibility standards for children have been stable since then (the figure below is from this paper). Before that SSA’s eligibility standards for children were expanded (in 1990 by a conservative Supreme Court that ruled 7-2 that SSA’s regulations were much stricter than the underlying federal law) and then pared back somewhat (by Congress in 1996 after the Gingrich Revolution). In telling the story of Supplemental Security today, the primary focus should be on trends from recent history that represent a mature, stable program. If reporters want to also tell the story of the implementation and early history of children’s SSI, that’s fine, but they should be clear it is a much different story that has limited relevance to contemporary policy debates. They should also go back and read this 1995 Forbes Media Critic piece, “Media Crusade Gone Haywire,” detailing the role that dubious sources and anecdotes fed the last major round of media hysteria on this issue.