November 05, 2012

Robert Samuelson sounds like he is really angry at American voters since it doesn’t look like they are following his advice. He therefore pulls out all the stops in misrepresenting the country’s economic situation in his column today.

He starts quickly, telling us in the second paragraph:

“There’s a triple threat to stronger economic growth. The first stems from the legacy of the 2007-09 financial crisis, which induced households and companies to shed debt and, more important, made both more cautious spenders. The second is an aging population that stunts expansion of the labor force. Finally, chronic deficits — caused increasingly by a surge of promised benefits — imply future spending cuts and/or tax increases, which might dampen economic growth.”

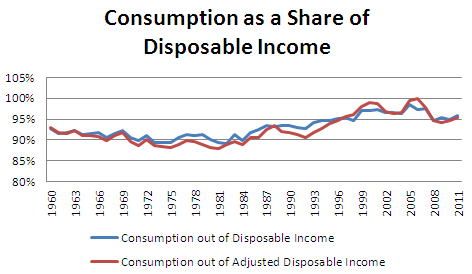

Okay, on the first point those with access to the Internet know that neither households nor businesses are especially cautious spenders at the moment. Here’s the consumption story brought to you by our friends at the Commerce Department.

Source; Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The story here is that while consumers are not spending as large a share of their income as they were at the peaks of the stock or housing bubbles, they are spending a larger share of their income today than they were on average in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, or even 1990s. (The adjusted consumption measure has to do with a technical issue, the statistical discrepancy in national income accounts.) So consumers are not being overly cautious, contrary to Samuelson’ assertion.

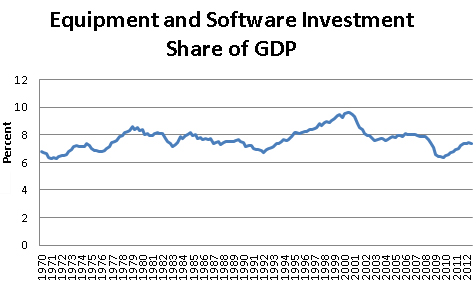

The Commerce Department’s data say the same about businesses. Here’s spending on equipment and software as a share of GDP.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Investment in equipment and software is down from the peaks of the Internet bubble, but pretty much back to its pre-recession share of GDP. It’s also pretty much back to Reagan’s Morning in America days. That’s pretty impressive given the large amounts of excess capacity in many sectors of the economy. It sure doesn’t look like businesses are being especially cautious.

What then explains the current weak economy? We had bubbles that led to enormous overbuilding in both the residential and non-residential sectors. As a result, construction continues to be depressed and will remain depressed until vacancy rates fall back to more normal levels.

The other reason is our large trade deficit. It is currently close to 4.0 percent of GDP ($600 billion a year) and would be near 5 percent of GDP ($750 billion a year) if the economy were near full employment. In the late 90s and the last decade the lost demand from the trade deficit was filled by demand generated by the stock and housing bubbles, respectively. There is nothing other than the budget deficit to fill the demand at present.

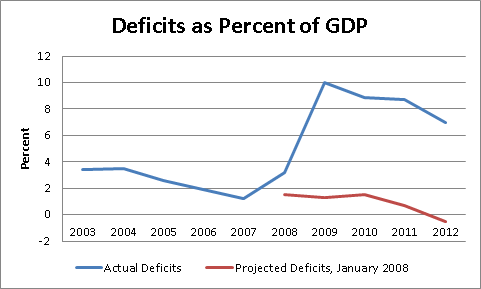

This gives us the opportunity to correct Samuelson’s third assertion. There were no big new unfunded spending programs or permanent tax cuts that led to the jump in deficits in recent years. It was entirely the result of the collapse of the economy. This caused tax collections to plummet and spending on items like unemployment insurance to rise. In addition, there were temporary stimulus measures, like the payroll tax cut, intended to provide a boost to the economy. However if the unemployment rate fell back to its pre-recession level, deficits would again be very modest as shown below.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

The deficits of just over 1.0 percent of GDP that we were seeing before the economy collapsed could have been sustained indefinitely even if the projected expiration of the Bush tax cuts did not push the budget into surplus. The debt to GDP ratio was falling at the time. Contrary to Samuelson’s assertion about the deficits being fueled by a “surge in promised benefits,” they were caused by a collapse of the economy, end of story.

Samuelson’s second point is also misleading. Insofar as most people are concerned about economic growth, it would be per capita growth that matters, not total growth. Insofar as growth slows because population growth is slowing, this is not in any obvious way an economic problem. In fact, since slower population means that the country will be less crowded, this slower growth is likely to provide benefits in ways not picked up in GDP data, such as less pollution.

Samuelson gets several other important items wrong in his piece. He tells us:

“Even before the financial crisis, the U.S. economy was decelerating. From 1991 to 2001, growth averaged 3.2 percent a year; from 2002 to 2011, the pace slipped to 2.3 percent.”

Of course 2011 was not before the financial crisis. (Actually, we should be focused on the collapse of the housing bubble, but that might be too technical for the Post’s opinion page.) Furthermore, it’s not clear what sort of comparison Samuelson thinks he is making. It is common for economists to look at growth comparisons between business cycle peaks. In this case, he has looked at the growth between the trough of a recession (1991) and the trough of a relatively mild recession (2001) and the near trough of a very severe recession (2011). This tells us much more about the depths of the recession than it does about the growth in the expansion.

Samuelson then gets supply and demand confused, telling readers:

“For Americans, the global nature of the political challenge means that we can’t rely on strong demand from Europe and Japan — buyers of 27 percent of U.S. exports in 2011 — for faster growth. Just the opposite: Their weakness threatens ours.”

Note that this is a demand story. The problem is that Europe and Japan are not buying our stuff. We actually know how to create demand, run budget deficits. It is very simple. Now Samuelson and his friends like to yell that budget deficits will create inflation — but wait boys and girls — that is a supply problem. Inflation is the story of too much money chasing too few goods and services.

Now you get an idea of how bad things will be in the future. According to Samuelson we will both be suffering from a lack of demand because there will be no one to buy our goods and services and we will also be suffering from a lack of supply as chronic budget deficits cause too much money to be chasing too few goods and services. Now that is a dire situation.

Maybe if people vote for Samuelson’s candidates in the future he will spare us from such mind-twisting conundrums.

Comments