We thank Alexandra Spratt and Hunter Kellett at Arnold Ventures for their financial support and intellectual guidance on this project. We thank colleagues at the Center for Economic and Policy Research and Americans for Financial Reform for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

A growing body of research has focused on the social and economic determinants that lead to health inequity among different population groups in the US. People in low-income communities face daily economic challenges, “food deserts,” inadequate housing, and other conditions that undermine their health and well-being.

The structural determinants of health inequity, however, are more hidden from view and have received less attention. By structural determinants we mean health care infrastructure – hospital facilities, technologies, equipment, and other resources – that are critical for health care professionals to deliver quality care to their patients. In this report, we focus on differences in hospitals’ access to capital to finance the construction or modernization of facilities, upgrades to the latest technology, and expansion of services to additional patient populations. Access to funding for capital projects has consequences for the growth of revenue and the financial stability of hospitals and for the quality of patient care.

Central to our argument is that federal government policies and funding formulas played a critical role in fostering these inequalities across health care systems in different communities, especially low-income and rural communities. Our evidence draws on our analysis of federal legislation and IRS tax rulings that have led different types of hospitals to have differential access to public subsidies and capital markets — resources necessary for the construction and upgrading of hospital facilities needed to deliver quality care.

We begin with the 1946 passage of the Hospital Survey and Construction Act known as the “Hill-Burton Act.” The Hill-Burton Act provided extensive public funding for the construction of nonprofit hospitals and was designed to remedy shortages of hospital capacity in poor and rural communities, a goal it largely succeeded in fulfilling. But Hill-Burton also incorporated the racist views and legally and socially enforced segregation of those times into the law, funding separate facilities for Black and white patients. This practice was halted in 1964, but Hill-Burton funding was the largest infusion of public funds to build a nationwide hospital infrastructure in the country’s history. The legacy of racial segregation, inferior hospitals, and worse health outcomes on average for Black patients persists to the present day.

The 1965 Medicare and Medicaid law, which supplanted Hill-Burton, contained a different set of hidden structural inequities. The law provided subsidies to hospitals intended to facilitate their ability to generate internal funds or access financial markets. The Medicare formulas for those subsidies, however, disadvantaged smaller hospitals and those with patient populations insured by Medicaid or not insured at all — especially “safety-net” and rural hospitals. Congressional actions to reduce the federal budget deficit led to an end to those subsidies in the 1990s, and the passage of the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, which substantially cut Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates. As a result, hospitals across the country faced financial distress and uncertainty. Even those that had benefited from decades of privileged access to federal resources, such as Academic Medical Centers, faced the prospect of sharp declines in net operating income.

An IRS ruling in 1998 disproportionately helped large nonprofit health care corporations and Academic Medical Centers to access a new source of funding for capital investments. The ruling allowed nonprofit hospitals to create for-profit subsidiaries whose profits were tax-exempt and could be used to subsidize investments in facilities and technology as well as financial activities such as mergers and acquisitions. The legacy of federal funding that disproportionately benefited larger nonprofit systems also positioned them to take advantage of this new ruling. Academic Medical Centers and large nonprofit systems launched partnerships with venture capital (VC) firms, raised funds from capital markets for infrastructure expansion, expanded merger and acquisition (M&A) activity, developed corporate structures, and offered higher compensation packages to CEOs and other executives.

By contrast, rural hospitals and those serving low-income Black, Indigenous, and immigrant communities had aging infrastructure that was most in need of repair and obsolete technologies that needed upgrades; yet they often faced greater challenges in access to capital for investments. This situation was largely unchallenged in the first two decades of the twenty-first century. Passage of the Affordable Care Act and its extension of Medicaid insurance to large swaths of previously uninsured Americans in many states improved the access of millions of people to health care and shored up the finances of hospitals caring for the poorest patients. But Medicaid reimbursements were not sufficiently generous to enable hospitals serving poor urban and rural populations to build up internal resources for financing capital improvement or to improve their access to external funding via financial markets.

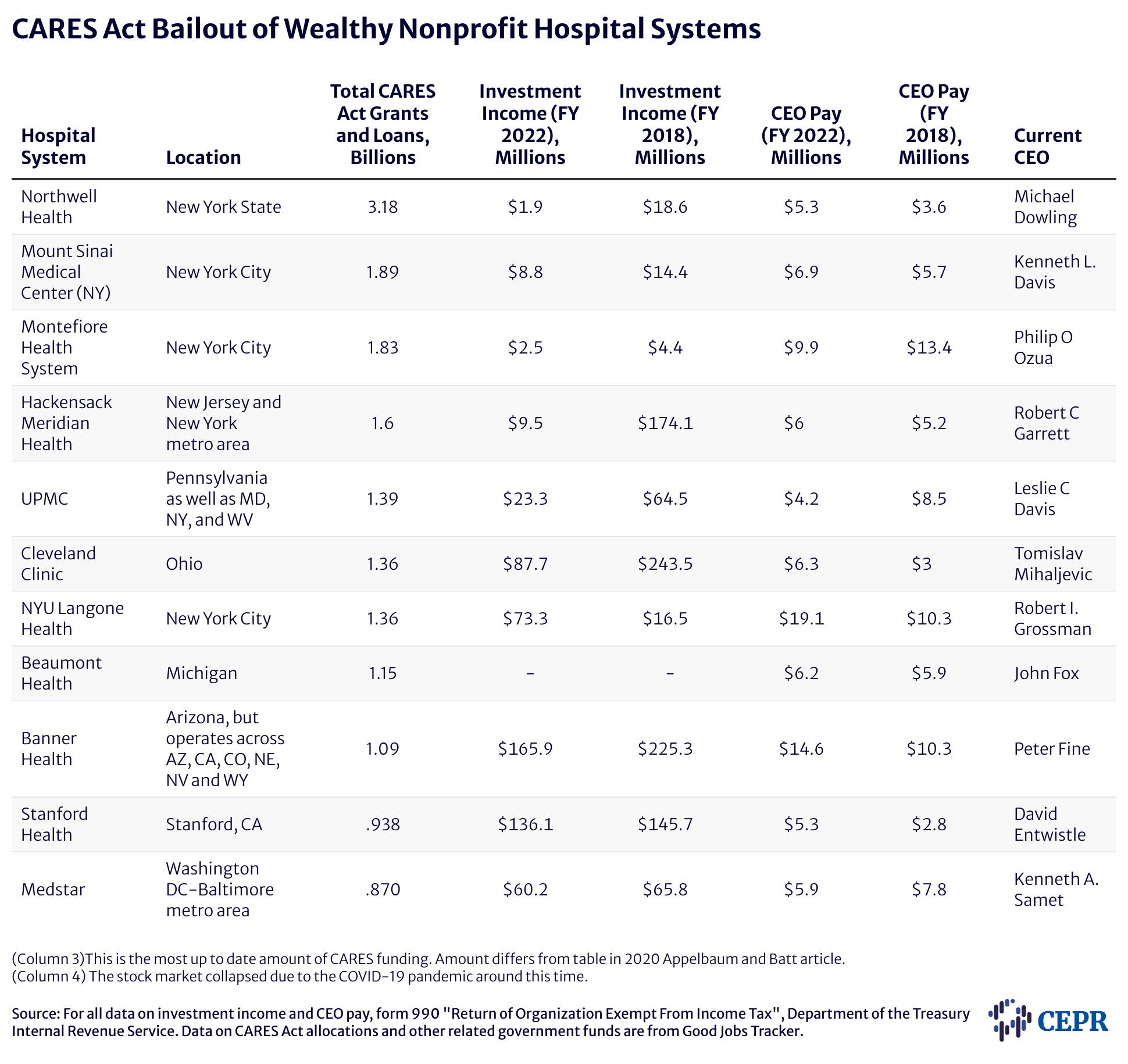

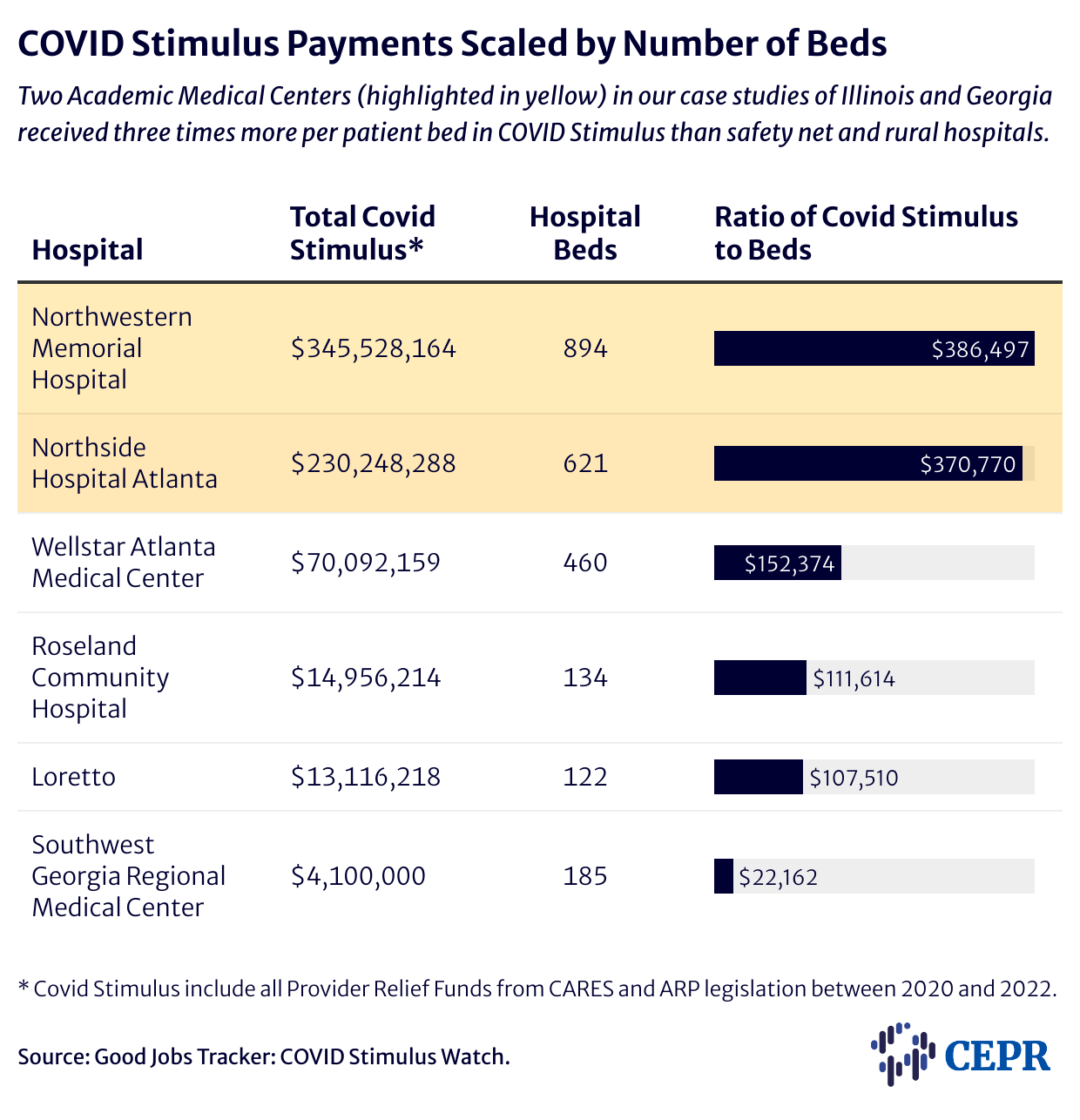

The COVID-19 pandemic particularly laid bare the inequities in facilities and technology in rural hospitals, safety-net hospitals, and the largely segregated urban hospitals that treated more Black patients and other people of color compared to white patients. Under the CARES Act of 2020, Congress allocated funds for hospitals to purchase ventilators, oxygen, remote monitoring equipment, personal protective equipment (PPE), and other safety equipment. But surprisingly, the formula for allocating these taxpayer dollars was based on the providers’ share of Medicare payments in a previous year. This disproportionately favored wealthier hospitals — those with higher Medicare reimbursements — over those with lower reimbursements or that were more dependent on Medicaid. This unequal allocation formula exacerbated the gap in the availability of equipment and supplies for rural and safety-net hospitals so vital to saving lives of COVID-19 patients and to providing quality care.

We develop each of these themes in this report.

US policymakers and regulators need to rethink the way that the government finances construction and modernization of health care facilities and technology upgrades. The first step might be a Hill-Burton Act for the twenty-first century that targets new construction, renovation, and modernization of hospitals in communities where it is most needed. Taxing profits above a threshold of for-profit subsidiaries of nonprofit hospitals could subsidize such an initiative.

Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) in 2010, the US has made significant advances in opening up access to health care for Americans. This is the result of subsidized health insurance premiums for low- to middle-income people and an expansion of Medicaid for low-income people in all but 10 states. Nevertheless, as COVID-19’s tragic effects on Black communities and communities of color showed, America’s health care system continues to provide much better health outcomes on average for white patients than for Black patients, immigrant communities, and for those in low-income urban and rural communities. Stark disparities in health outcomes remain despite improvements in the ability of Americans to access care.

A main approach to understanding differences in health outcomes is to examine the social determinants of health (Pifer 2023) — the social and economic forces that shape people’s lived experience and their health. In contrast, the focus of analysis in this paper might best be referred to as the structural determinants of health, the relationship between the quality of the physical facilities, equipment, and technology, and the safety and quality of patient care. We build on our earlier work in which we examined how health policies, financial deregulation, tax policy, and antitrust policy have interacted to shape the US health system. In particular, hospitals’ unequal access to financial resources has contributed to disparities in the quality of hospitals’ physical infrastructure. Public financing of hospital construction, renovation, and modernization that characterized the two decades following World War II gave way in the 1960s to reliance on financial markets to fund capital projects. Unequal access to financial markets has disadvantaged small hospitals and hospitals that serve poor or rural communities. Academic Medical Centers, in contrast, were able to take advantage of changes in financing that both enriched hospital leadership and provided them with the most modern facilities and cutting edge technologies. In this paper, we examine the impacts of disparities in the quality of hospitals’ physical infrastructure on patient safety and the quality of care.

Investigations into the reasons that health outcomes are so much better on average for Asian1 and white patients than for Black people, Hispanic people, American Indian and Alaska Native people, and other people of color (Hill, Ndugga and Artiga 2024) point to inequities that exist outside the health care system. Social and economic disparities — housing segregation, income inequality, unemployment, homelessness, food deserts, and lack of transportation — negatively affect health outcomes in disadvantaged communities. Black communities and communities of color also experience higher rates of exposure to environmental hazards that affect health, like water pollution, lead poisoning, smog from industrial sites, and emissions from cars. They are also less likely to have access to health care and are likely to utilize health services less frequently.

These long-standing systems of racial bias are difficult to eradicate. Disparities in rates of serious illness and death among different racial groups during the pandemic made it impossible to ignore the serious effects of these inequities on individuals’ health outcomes. “Social determinants of health” have become increasingly prominent in research on health outcomes, with the negative effects of deprivation and marginalization on individuals’ experiences of illness garnering attention. Social inequities that affect the health of women have been singled out as contributing to the stark differences in rates of maternal deaths between Black and white women. According to the Centers for Disease Control, 754 women died of maternal causes in 2019 (Hoyert 2021). Non-Hispanic Black women experienced 44 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. The rate for non-Hispanic white women was 17.9 and for Hispanic women, it was 12.6. Black women were 2.5 times as likely to die in childbirth or from related causes as white women.

Policymakers have begun to make efforts to address the social determinants of health via interventions designed to help individuals. Screening and referrals by primary care doctors to food assistance, housing programs, nonemergency medical transportation, and community-based care coordination were examined in a simulated study of the cost of these interventions (Basu et al. 2023). This study found that many resources are required to address social needs and that they are largely not included in existing federal programs. Just under half the cost of the interventions was covered by programs like SNAP or housing vouchers, due mainly to capacity constraints in those programs. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is exploring ways to improve health equity and to measure it when evaluating the quality of care provided to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries by health providers. However, CMS is limited in what it can do by the fact that it is mainly authorized to reimburse health providers. It recently launched a pilot project to increase payments to primary doctors with the added funds to be used to implement technologies that allow them to better coordinate with social service providers and medical specialists (Olsen 2023; Pifer 2023).

A recent study of racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes from the Commonwealth Fund finds wide gaps in health outcomes, with outcomes for the Asian population the best of any group and outcomes for the white population better in general than for people of color (Radley et al. 2024). The gap is largest for the Black population. A salient finding is that, nationwide, Black people are about twice as likely to die before the age of 75 from treatable causes compared with white people. The disparities are much lower in some states and generally highest in the 10 states that still have not participated in the Medicaid expansion authorized in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The Commonwealth Fund study collected data on nine measures of individuals’ health outcomes, five measures of their health access, and 11 measures of their use of health services. It is comprehensive and provides a useful guide to policy measures that can be implemented at the state and local levels to serve underserved communities and reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes. The policies address some of the most important social determinants of health and seek to improve health outcomes by increasing individuals’ access to and use of a wide array of health services.

This is an important study and the policies it reviews are likely to play a critical role in improving health outcomes. Missing in the Commonwealth Fund study, however, and in nearly all research on disparate health outcomes, is an understanding of how differences in facilities and technology — literally in the quality of the physical structures of hospitals, clinics, and offices where health care is delivered — affect the ability of health professionals to deliver quality care, and in turn, the health outcomes of their patients. That is the focus of this report.

In this report, we highlight a more hidden source of inequality in health care systems. Our focus is on differences in hospitals’ access to the capital needed to finance the construction of new facilities or modernization of buildings, heating and ventilation systems, medical equipment and devices, hardware and software technologies; and expansion of services to additional patient populations. We refer to this through the report as hospitals’ physical infrastructure. Access to funding for capital projects has consequences for the growth of revenue, the financial stability of hospitals (Hudson 2024), and the quality of patient care. The American Hospital Association (AHA) (2021) has noted the aging of hospital infrastructure. It cautioned that the hospitals most in need of infrastructure upgrades may face the greatest challenges in accessing financing for capital investments. In particular, hospitals serving what the AHA refers to as medically underserved populations find it difficult to “update their facilities and remain an access point to care in their communities” (2021:1).

Building on our prior work on the financialization of health care and our analysis of how government funds have been allocated to hospitals and other providers, we argue that unequal access to public funding and financial markets over the last 75 years has led to stark inequalities among health systems in construction and modernization of facilities and in upgrading technology and to a two-tier system of care. Financially stressed hospitals, notably those serving poor urban and rural communities, typically lack modern facilities and up-to-date technology as well as specialists, and may not have access to cutting-edge procedures that can save patients’ lives. They may lack resources even to address patient and worker safety issues. Contrast that with the level of care available at the flagship hospitals of academic medical centers (AMCs), which boast the most modern technology, surgical theaters, and intensive care units as well as a physical setting worthy of a first-class hotel. These disparities contribute to poorer health outcomes observed for Black patients and patients of color relative to white patients (Sarkar 2020; Lasser et al. 2021).

The quality of physical infrastructure affects patient safety (e.g., falls and hip fractures, ulcerated bed sores, hospital-acquired infections) and health outcomes (patients’ perceptions of care, 30-day hospital readmission rates) (Akinleye, McNutt, Lazariu, and McLaughlin 2019). The argument is that a hospital’s financial performance, including operating margins as a proxy for cash flow (Traska 1988), affects its ability to obtain funding for capital investments, hire better-qualified staff, and make costly investments in quality improvement projects (Akinleye, McNutt, Lazariu, and McLaughlin 2019). Hospitals that are profitable are able to repay debt quicker. This enables them to obtain further financing for capital projects at a lower cost than hospitals that are struggling financially. The financing also makes it possible for these hospitals to make upgrades to critical technologies and patient monitoring systems. Improvements in hospital quality and patient safety can be costly to implement and may be limited or foregone by hospitals with poorer financial performance.

An analysis of financial distress in the years 2011 to 2018 found that nearly a quarter of hospitals faced financial distress in each year of the study. For-profit hospitals and those with a higher share of Medicaid revenue were found to have increased odds of financial distress (Enumah and Chang 2021). Three earlier studies of financial distress by the American Hospital Association (AHA), AHA-Urban Institute, and the National Center for Health Services Research carried out in the 1980s found between 20 and 27 percent of hospitals nationally were experiencing financial distress and, further, that the cause of this distress, especially for distressed urban hospitals, arose because they played a large role in caring for uninsured or underinsured patients rather than because of poor or inefficient management (Brecher and Nesbitt 1985). Financial losses lead to less access to capital and higher borrowing costs, constraining investment in critical new technologies (Duffy and Friedman 1993) and in activities to improve quality and safety. Negligent injuries were highest among hospitals in financial distress, many of which served indigent populations (Burstin, Lipsitz, Udvarhelyi, and Brennan 1993). The probability of poor surgical care was higher in safety-net hospitals than in other hospitals (Mouch et al. 2013) and the incidence of immediate breast reconstruction after surgery for breast cancer was lower in hospitals serving disadvantaged patients (Richards 2014). These findings suggest that increased financial pressure leads to declines in investment in infrastructure, including technology, and in measures to improve care. The phasing out of public financing of capital improvements (discussed below in Section 2) has led to a lack of funding for investment in capital improvements or in measures that improve care in safety-net hospitals (Sherlock 1986), which can increase mortality and morbidity rates (Duffy and Friedman 1993).

Tragically, the COVID-19 pandemic provided a context in which researchers could analyze the factors that contributed to deaths from the disease. Black patients were more likely to die than white patients, but was the difference related to race, or were there other factors that determined patient outcomes? The earliest studies were based on relatively small samples of patients treated by single health systems. These studies found that differences in demographic factors (age, gender) and comorbidities (obesity, diabetes, other chronic conditions) explained the observed differences in mortality rates. Asch, Islam, and colleagues (2021) used the large population of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with COVID-19 to carry out a more comprehensive analysis of the factors contributing to the higher mortality of Black patients compared to white patients. They were interested in understanding whether the hospitals where patients were treated also impacted death rates for Black and white patients. To answer this question, the researchers analyzed a cohort of 44,212 Medicare Advantage enrollees with a diagnosis of COVID-19 who were admitted to 1188 acute care hospitals between January 1, 2020, and September 21, 2020, overcoming the sample size and single health system limitations of other studies. This sample was not only much larger, but it was also likely to be more heterogeneous than those in studies that found no role for race in explaining the observed disparity in mortality between Black and white COVID-19 patients.

The researchers first carried out the analysis of this disparity by examining the association between mortality and a wide range of personal characteristics and comorbidities. Mortality is defined in this study as death or discharge to hospice within 30 days of admission to the hospital. They adjusted the mortality rates of Black and white patients for age, sex, income level, zip code, 23 specific comorbidities, and admission to hospital from a nursing facility. They also adjusted for the number of days between January 1, 2020, and the date of admission to account for likely improvements in patient outcomes as hospitals gained experience, for census regions to account for geographic variation in care, and for COVID-19 surges over time.

To examine the association with the hospital itself, the researchers adjusted for the specific hospitals to which patients were admitted. Finally, they used simulation modeling to estimate the mortality among Black patients had they instead been admitted to the hospitals where white patients were admitted. But Black patients still had greater 30-day odds of inpatient mortality or discharge to hospice compared with white patients. Black patients had an adjusted risk of mortality that was greater than white patients, 12.32 percent compared with 11.27 percent. The difference is statistically significant. However, after further adjustment for hospital-level fixed effects (basic characteristics such as number of beds, ownership status, and others) of the admitting hospital, mortality outcomes for Black patients were not statistically different than for white patients. The hospital at which a patient was treated made a difference in their chances of dying from COVID-19.

Black patients were disproportionately treated in hospitals with higher proportions of Black patients. In the simulation exercise, the researchers found that had the Black patients been assigned to the same hospitals as white patients and in the same proportions, their risk of mortality from COVID-19 would have been significantly reduced.

The researchers conclude that differences in the mortality outcomes of Black and white patients “were partly explained by adjustment for social, demographic, and clinical factors.” But “even after adjustment for those factors, racial differences in the mortality of patients” remained. “Those differences are almost entirely explained by the hospitals to which Black and White patients were admitted.” The researchers point to “uneven resourcing and quality of hospitals that provide care to a disproportionate number of Black patients” as a key source of higher death rates for Black COVID-19 patients (Asch and Islam et al. 2021: online page 9/11).

A recent study of a large-scale intervention by the philanthropy Duke Endowment that upgraded the physical infrastructure of hospitals in North Carolina in the first half of the twentieth century demonstrates the positive effects of such investments on health outcomes. The researchers examined the effects of the modernization of hospitals’ physical facilities on the death rates of Black and white infants. They found that the upgrading of facilities made possible by Duke Endowment’s financing of hospital modernization led to a 7.5 percent reduction in the infant mortality rate — a drop of 13.6 percent for Black infants and 4.7 percent for white infants. The effects of these improvements in hospitals’ physical infrastructure led to better quality patient care that persisted for decades. They attributed this to complementarity between the quality of hospital infrastructure, attraction of higher skilled physicians, and adoption of health care innovations (Hollingsworth, Karbownik, Thomasson and Wray (2024).

Studies of the role of hospital quality rarely examine the quality of the hospital’s built environment. The exception is research on rural hospitals. Here it is more obvious that disparities in investments in renovation and modernization have left the facilities in poor physical condition and unable to meet high standards of care. Operating rooms may be too small to utilize the latest technology to perform particular surgeries for example, and the hospitals are generally less able to provide the highest quality care. A great many rural hospitals were built with public funds appropriated in the Hill-Burton Act, discussed below. This source of funding ended in 1997. Hospitals built with these funds are anywhere from 35 to 60 years old or older and face the challenge of upgrading their facilities as they receive reduced payments for their services from public and private insurance payers. The aging infrastructure of rural hospitals is a major worry for the communities they serve. Most rural hospitals operate at very low margins and may be unattractive to private lenders. They find it difficult to “qualify for loans or other types of financing to upgrade their facilities to meet the ever-changing standards of medical care” (Hawryluk 2024).

Disparities in access to funding for hospitals’ investment in facilities lie in laws and regulations dating back to at least the end of WWII and their evolution in the following decades — health policies, financial deregulation, tax rules, and the reversal in anti-trust guidelines. The legal framework is a patchwork of different laws and regulations with different incentive structures that were enacted without reference to one another (Appendix Table 1). The most important laws and regulations include health care policy (1946 Hill-Burton Act, 1965 Medicare and Medicaid Act, 2010 Affordable Care Act); tax policy (1960 Real Estate Investment Trust (REIT) Act, 1969 IRS ruling that expanded what counts as charitable purposes so that a hospital’s charity care did not need to include care of the indigent and a 1998 IRS ruling that allowed nonprofit hospitals to set up tax-exempt for-profit subsidiaries); anti-trust policy (including the reversal in antitrust guidelines during the Reagan administration that promoted consolidation); and financial deregulation (including changes in pension law) that opened large pools of capital for investment by Wall Street firms.

As we discuss in Section 2, the Hill-Burton Act of 1946 provided public funds for the construction of nonprofit hospitals, nursing homes, and clinics. The Act greatly expanded the available number of beds and increased access to such facilities by building many of them in counties that in 1945 had no hospital. The Hill-Burton Act is a story of successful investment in medical infrastructure, but it is also a tale of perpetuating segregation. It officially institutionalized structural racism by financing “separate but equal facilities” that often were not equal and spurred unequal access to funds for the construction and modernization of hospitals and facilities that served Black communities.

Public financing of hospital construction was phased out over a period of nearly three decades after the legislation authorizing Medicare and Medicaid was implemented. Medicare, as we discuss in Section 3, subsidized the costs of new construction as well as modernization of existing facilities. It provided hospitals — including, for the first time, for-profit and nonprofit hospitals — a subsidy that covered capital costs such as interest on debt, including debt incurred in acquiring other hospitals, as well as depreciation. It also included an add-on of 2 percent of these costs for the construction of new facilities. Unlike Hill-Burton funding, the subsidies did not cover the actual cost of the capital investment. What it covered was the cost of capital, mainly interest on borrowed funds and depreciation. Nonprofits were now competing directly with for-profit hospitals in financial markets for funding for the construction and modernization of facilities. Funding sources for capital projects of nonprofit hospitals, including charitable grants from wealthy donors and government grants and appropriations, fell steeply from 44 percent in 1968 to just 16 percent in 1981 of investments in hospital infrastructure. This decrease meant that nonprofit hospitals increasingly relied on borrowing in financial markets to raise funds for investment in facilities and technology. Nonprofit hospitals were held to the same underwriting standards as for-profit hospitals when borrowing in financial markets (Heshmat 1992). This disadvantaged small hospitals and hospitals serving uninsured and underinsured patients in poor urban and rural communities that could not meet the financial performance requirements to qualify for these loans.

For-profit hospitals also received a premium so that they could pay dividends to their shareholders. (Grogan 2023). These subsidies allowed for-profit hospitals, with their prior relationships with financial market actors, to obtain nearly risk-free loans for the construction of new facilities and the acquisition of existing health organizations as they built large chains (Fox and Schaffer 1991). The change in antitrust guidelines allowed these hospital mergers to proceed unchallenged.

Changes in rules on the use of tax-free bonds by nonprofit hospitals opened up their access to financial markets for construction and modernization. But the playing field wasn’t level as the legacy of structural racism denied access to financial markets for some hospitals. The Medicare subsidies provided assurances that loans could be repaid. But lenders applied the usual underwriting criteria nevertheless, and favored hospitals in more affluent neighborhoods, those with a payer mix that included commercial health insurers as well as Medicare, and those that typically served mostly white patients. Black, Brown, and poor white communities in urban and rural areas were often unable to access funds for the construction of new facilities or for upgrading existing buildings and technology (Grogan 2023).

The 1998 change in IRS guidelines allowed nonprofit hospitals to own, tax-free, for-profit subsidiaries. We examine the effects of this on disparities in physical infrastructure and patient outcomes in Section 4. The tax guidance set the stage for an alliance between academic medical centers (AMCs) or other large nonprofit hospitals with a capacity for medical research on the one hand and venture capital firms that sponsored start-ups on the other. This alliance of health care and Silicon Valley was established to create patentable medical products and processes. While initially a lifeline to cash-strapped hospitals hurt by Congressional budget balancing cuts and a shift in Medicare spending from AMCs to hospitals treating a disproportionate share of poor patients, this alliance with venture capital soon turned into a windfall. It enriched some of the most well-endowed hospitals in the US, exacerbating inequalities in facilities and their ability to treat patients. In principle, these nonprofit hospitals could afford to offer reduced cost or free care to poor patients which would mitigate the effects of disparities in the quality of facilities. But in fact many spent less on the care of indigent patients than they received in tax breaks. Some even refused to accept transfers of patients during the COVID-19 pandemic from hospitals that lacked life-saving equipment even when they had empty beds (Schorsch 2020).

The challenges facing rural hospitals with aging facilities and technology are discussed in Section 5. These hospitals play a major role in securing the health of rural populations and often are major economic anchor institutions providing stable employment to residents of their community. Maintaining these facilities, and renovating them to meet changes in patient preferences and how hospitals best treat patients, is key to the vitality of rural communities. But rural hospitals face major challenges to their ability to upgrade facilities and technology, staffing, financing, low patient volumes, and aging infrastructure. Their small size, thin margins, and heavy reliance on Medicaid as payers puts many of these hospitals at a disadvantage. Keeping up with advances in physical infrastructure including technology and equipment requires high operating margins. High margins facilitate the accumulation of internal reserves for construction as well as the ability to borrow in financial markets. Hospitals that can invest in facilities and technology are able to attract patients and doctors. They are on an upward trajectory. Less fortunate hospitals that lack access to funds for construction, renovation, and modernization will lose patients and have difficulty recruiting and retaining physicians. They will find themselves on a downward trajectory and, if something doesn’t intervene, will continue to wither and fail. In light of the important role that they play, can they be restored to health?

The disparities in access to funding came to a head during the COVID-19 pandemic, as we discuss in Section 6. The all-important first tranche of funding from the CARES Act early in the pandemic was distributed with no strings attached to health organizations based on the share of Medicare (but not Medicaid or charity care) patients the provider organization had treated in the preceding year. A nontrivial part of the explanation of higher COVID-19 death rates in Black communities compared to white communities rests with the hospitals in which Black patients were treated.

The Conclusion looks at the urgent need to address and remedy disparities in physical infrastructure and technology among hospitals. Current methods of funding hospitals’ capital investments widen the inequities in hospital infrastructure and the quality of patient care.

The Hospital Survey and Construction Act of 1946 — which came to be known as the “Hill-Burton Act” — is one of the largest federal investments in hospitals and other medical facilities in United States history. Following World War II, President Harry Truman presented five goals to improve the health of Americans. The least controversial of these was his call to construct hospitals and clinics to serve a growing population (Schumann 2016). Congress responded with the Hill-Burton Act,

The main goal of Hill-Burton was to increase the number of hospital beds available across the country from the insufficient level of 3.2 beds per 1,000 civilian population in 1945 to 4.5 beds per 1,000 (Chung, Gaynor, and Richards-Shubik 2016). Demand for hospital beds far outran supply following the end of World War II. The Hill-Burton Act provided $75 million a year for five years in grants to states for hospital construction beginning in 1947. In 2023 dollars, this is about $1.06 billion. The amount was raised to $150 million in 1949, which is $2.1 billion in 2023 dollars. Hill-Burton also provided substantial funding so that states could conduct surveys to determine how to allocate construction loans and grants. In total, between 1946 and 1971, a total of $3.7 billion in federal funding and $9.1 billion in matching funds from state and local governments was allocated (Clark et al. 1980). In the decades that followed 1946, general hospitals, mental hospitals, tuberculosis/chronic disease hospitals, public health centers, nursing homes, diagnostic and treatment centers, and rehabilitation centers were built all around the US.

Over that period, there were a total of 10,490 projects funded by the Hill-Burton program. Of these, there were 5,567 projects focused on short-term general hospitals. The program was designed to remedy perceived shortages of hospital capacity in poor and rural communities. These factors played an important role in how the funds were distributed and in the increase in the supply of hospital beds per 1,000 population. Geographic areas with a low supply of beds per 1,000 in 1947 mostly caught up with areas that had more hospital capacity by 1971. The South added more beds per 1,000 than the Northeast. Rural areas had the largest increases. Across counties, the variation in beds per 1,000 narrowed considerably; it fell by more than half between 1948 and 1975. Substantial progress was made in expanding the number of hospital beds in poor and rural areas and making access to hospitals more equal throughout the US. Hospital admissions increased in line with the increase in hospital capacity. These results suggest that the Hill-Burton program had a substantial net positive on hospital capacity and the distribution of hospital beds in the US as well as on access and utilization (Chung, Gaynor and Shubik 2016).

Until the passage of the Hill-Burton Act, there were no hospitals in many parts of the rural South. The hospitals were almost entirely racially segregated into different facilities, and there was a lack of investment in the Black facilities (Beardsley 1987). The small number that did exist were mostly small, poorly equipped private institutions concentrated in urban areas, and largely closed to Black patients (Thomas 2008). The alternative to the white facilities were the small hospitals and nurses’ training schools run by Black physicians. Before the 1930s these were often the only places where Black people could go for medical attention (Beardsley 1987, 37). In 1940 in 16 southern states, 9.7 million African Americans were served by 79 black hospitals, most of which were unaccredited, underequipped, and struggling to keep their doors open (Thomas 2006). There was also a lack of personnel, lack of training for Black medical professionals, and discrimination in their hiring.

The idea of Hill-Burton was to provide funds to communities in need so long as they could demonstrate that a hospital or other medical facility would be sustainable based on the communities’ population and per capita income. Forty percent of counties that did not have a hospital in 1945 saw construction break ground. Many of these new hospitals and other medical facilities were in the South and more grant money went to low-income states (Lave and Lave 1974, 17).

The Hill-Burton Act is a story of successful investment in medical infrastructure, but it is also a tale of perpetuating racial segregation. The legislation’s nondiscrimination clause required that hospitals built with federal Hill-Burton money admit all people regardless of “race, creed, or color.” However, there was a catch. States that already had “separate but equal facilities … for separate population groups” could ignore the nondiscrimination provision so long as they supplied Black people with enough facilities and services “of like quality” to meet the assessed need (Beardsley 1987, 178; Thomas 2006, 839). The Act institutionalized existing patterns of discrimination and enshrined “separate but equal” into the US hospital system. By legally sanctioning hospitals to continue existing patterns of discrimination, the Hill-Burton Act reinforced structural racism and appeased pro-segregation Southern lawmakers who demanded the independence of state legislatures (Largent 2018).

The nature of segregation in hospitals and other facilities went from “spatial isolation in completely separate buildings to the partitioning of racial groups within shared structures via separate entrances, floors, wards, etc.” (Thomas 2006). The federal Public Health Service (PHS), which today is part of the Department of Health and Human Services, accepted statewide hospital plans that included segregated institutions as long as the state health planning agency considered these facilities adequate for the population served. As Edward Beardsley wrote in his 1987 book, Hill-Burton “left it to Southern states (and the surgeon general as final arbiter) to decide how much blacks needed” (178).

In Congressional debates at the time, some Senators, Northerners in particular, spoke out against discrimination and argued that no federal funds should go to hospitals that practiced segregation. Southern Democratic segregationists argued for states’ rights and letting hospitals set their own policies. The compromise language prohibited outright discrimination by race but permitted separate but equal funding for hospital construction (Harvard University 2020). The provision was the only one in federal legislation of the 20th century that explicitly permitted the use of federal funds to provide racially exclusionary services (Largent 2018). By 1975, a third of all hospitals in the US had been constructed using Hill-Burton funding.

Direct federal funding of hospital and health facilities construction ended in 1997. By that time, the Hill-Burton Act had partly financed about 6,800 facilities in 4,000 communities, including hospitals, clinics, rehabilitation centers, nursing homes, and long-term care facilities (Clark et al.1980). By this point, Hill-Burton was folded into bigger legislation called the Public Health Services Act. Data from 10 years after the Hill-Burton Act’s passage showed that fully integrated hospitals where Black people were admitted to any available hospital bed were rare (Cornely 1956).

For most of the hospitals that received Hill-Burton funds, the separate Black wings that were constructed had poorer nurse staffing, fewer visiting hours for families, and the facilities were outdated and crowded. Black physicians were barred from treating patients throughout the wards. Through the 1950s, most Hill-Burton hospitals, especially in the South, remained closed to Black medical interns, refused to employ Black residents, and generally denied Black physicians the opportunity to treat Black patients (Beardsley 1987).

Black physicians were a well organized, elemental group in the movement to end hospital segregation (Beardsley 1987). There was a wide range of opinions within the Black community towards how the hospital system should progress. Black physicians in the National Medical Association promoted federal enforcement of racial parity in health care and were staunchly against the original version of Hill-Burton, whereas other groups of Black physicians and civil rights leaders were in favor of increased funding even if it came with strings attached (Meltsner 1966). The American Medical Association, one of the largest associations of physicians, was silent on the development of the Civil Rights Act and put off requests to amend Hill-Burton’s “separate but equal” provision.

Litigation over discrimination in the medical facilities was limited and received little public attention for about two decades following the 1946 Hill-Burton passage. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) led several lawsuits to eliminate discrimination in hospitals.

Finally, in the 1963 case Simkins v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, the NAACP succeeded in having a US Court of Appeals overturn the “separate but equal” part of Hill-Burton. At the time there were only nine hospitals that served Black people in all of North Carolina. The Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital and the L. Richardson Memorial Hospital in Greensboro had received funds from Hill-Burton even though they were both closed to Black patients because the state regulatory body had approved it.

The critical argument of the case was not centered around the differences in the facilities that treated Black and white patients, even though this was certainly occurring. Instead, George Simkins, along with other Black doctors in the state who were supported by the NAACP, made the argument that these private institutions were engaged in “state action” because they received Hill-Burton funds, and thus were subject to the US Constitution’s prohibition of racial discrimination under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. The court agreed and ruled that the Public Health Service Regulations set in motion by Hill-Burton of providing separate but equal services in Hill-Burton hospitals were unconstitutional. (Thomas 2006).

Legal precedent for hospital integration continued to build on a national level. A year later in 1964, the Civil Rights Act was passed. All facilities receiving federal funds like Hill-Burton were required to abide by Title VI, which said that “no person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance” (US Department of Justice). This legislation was a vital step towards preventing federal funds from going to public and private institutions open to the public that discriminated against Black Americans (US Commission on Civil Rights). Yet, the task of desegregating hospitals was enormous. Survey data showed that in early 1966 only 42 percent of hospital beds in the US were in hospitals that were compliant with Title VI.

In 1966, after being signed into law by President Johnson the year prior, the Medicare program went into effect and became a critical tool in the push toward stopping hospital facility segregation. Suddenly, the federal government would pay millions for the care of elderly and disabled people. Strategically, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare was directed by President Johnson’s Administration to require immediate integration if hospitals wanted to receive their Medicare certification and open the spigot of Medicare money.

Many Southern hospitals threatened to forego Medicare funding and deny care to seniors. A pressure campaign by members of President Lyndon Johnson’s administration averted that disaster, and hospitals all over the country, including in the South, desegregated (Harvard University Center for the History of Medicine at Countway Library 2020; Reynolds 2004). By July 1966, 2,000 hospitals integrated (Ross 2015). If not for the passage of Medicare and its strong enforcement by Johnson’s administration, lawyers and groups like the NAACP would have had to take each individual health care facility to court with resources they didn’t have (Smith 2016).

There are lasting impacts of Hill-Burton: Black patients are overwhelmingly treated in a small number of hospitals that mainly treat Black patients. A Harvard University study of the 4,455 medical and surgical hospitals in the US that treated Medicare patients in 2004 found that just 222 of these hospitals treated a disproportionate number of Black Medicare beneficiaries. These 222 hospitals, just five percent of hospitals with the highest volume of Black patients, cared for nearly 44 percent of all elderly Black Medicare patients. The top five percent with the highest share of Black patients cared for approximately 23 percent of Black seniors. In contrast, the top five percent with the highest volume of white patients provided care for 23 percent of white seniors, while the five percent with the highest share of white patients cared for just 0.7 percent of white Medicare beneficiaries (Jha, Orav, Li and Epstein (2007).

The segregation of elderly Black patients had deadly effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Black COVID-19 patients were substantially more likely than their white counterparts to die from the disease. The large-scale study of COVID-19 deaths described earlier in Section 1.2 (Asch and Islam 2021) found that Black patients were disproportionately treated in hospitals with higher proportions of Black patients (See Figure below). In the simulation exercise they conducted, the researchers found that had the Black patients been assigned to the same hospitals as white patients and in the same proportions, their risk of mortality from COVID-19 would have been significantly reduced. They point to differences in the quality of hospitals as a key source of higher death rates for Black COVID-19 patients.

The 1965 amendments to the Social Security Act established the Medicare and Medicaid programs, currently overseen by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). This legislation had a profound effect on the US health system. In addition to its familiar role of providing federal health insurance for people over age 65 and certain people with disabilities, Medicare also provided payments to hospitals to cover their capital costs. Medicare displaced Hill-Burton, which was gradually phased out, as the major source of public funding for modernization and new construction of hospitals and other health facilities. Direct funding of nonprofit hospital construction under Hill-Burton ended in 1997.

Medicare legislation had a serious impact on the delivery of health care by hospitals in two ways. First, it subsidized capital costs for both for-profit and nonprofit hospitals, the first time that for-profit health organizations received public funds. Medicare provided payments to hospitals for existing capital-related costs such as interest on debt, including debt incurred in acquiring other hospitals, insurance, and depreciation. For a time, Medicare also provided a 2 percent add-on for capital improvements. In effect, Medicare provided a subsidy to hospitals for construction of facilities by covering associated capital costs. Importantly, however, it did not cover the actual costs of construction and modernization. This was a new situation for nonprofit hospitals. Much of the costs for building and modernizing facilities had been covered under Hill-Burton, especially in the case of hospitals serving poor or rural communities. As had always been true of for-profit hospitals, nonprofit hospitals would now have to seek all of that funding in financial markets (Grogan 2023; Mayes and Berenson 2006 ).

Second, Medicare greatly increased hospital admissions by increasing access to health care among the nation’s elderly. It reimbursed hospitals for the care of beneficiaries by reimbursing the fees charged for medical care of hospitalized seniors on a cost-plus basis. This substantially reduced financial pressures on hospitals. In addition, Medicaid reduced the amount of uncompensated or charity care provided by hospitals, thus improving their bottom lines (Mayes and Berenson 2006).

Medicare’s payments to hospitals to cover the costs associated with investments in capital (interest on debt incurred in construction or acquisition of facilities as well as, depreciation, and insurance) acted as a subsidy to hospitals. These payments were larger for more successful and better-endowed hospitals as these were more likely to have engaged in expansion via new construction and acquisition and thus to have higher interest payments and depreciation. The Medicare subsidy made the issuance of tax-free municipal bonds by larger nonprofits attractive to lenders. These hospitals were able to raise funds for capital investments by issuing municipal bonds. Subsidies to smaller and/or poorer hospitals were less generous and, in the case of hospitals that were struggling financially, these payments were often used to meet operating expenses. As a result, access to financing for capital expenditures via financial markets was very uneven. It reinforced disparities among nonprofit hospitals in the quality of their physical plant. Issuing tax-free municipal bonds to finance the construction of facilities was daunting for smaller hospitals and those that served a high number of poor, uninsured, or underinsured patients. These hospitals were not seen as good credit risks, and their difficulties obtaining funding for capital investments widened the gaps among hospitals in the quality of facilities.2

But municipal bonds were not a panacea. Wall Street banks lost no time marketing risky financial instruments to hospitals to reduce their interest payments on the bonds. Rising interest rates in the 1970s and early 1980s were a challenge for hospitals. The main risk in the two and a half decades preceding the bursting of the housing bubble and the financial crisis of 2008–2009 was that interest rates would increase. Lenders demanded variable rate bonds when lending long-term, and Wall Street banks peddled derivatives to nonprofit hospitals without explaining the downside risks or offering a hedge against a decline in interest rates.

Nonprofit hospitals made use of two main financial instruments to manage the risk that interest rates might rise: interest rate swaps and auction rate securities. Interest rate swaps changed the type of interest rate they had to pay from a variable rate to a fixed rate. Many nonprofit hospitals used such swaps to exchange their variable rate bonds for fixed rates paid to a bank. If interest rates were to rise above the fixed rate, the bank would be the loser. The risk has been shifted to the bank. But if interest rates fell below the fixed rate, the hospital would be the losing party. The risks to the hospital from engaging in the swap were downplayed by banks. By 2005, swaps were used by 70 percent of large hospitals (Cleverly and Baserman 2005:364) convinced by Wall Street banks that interest rates were low and could only rise. They were lured by the false pretense that interest rates could not get any lower (Dugan 2010:1).

Unfortunately for the nonprofit hospitals, interest rates could, and would, fall. Banks were on the hook for major losses. Facing the prospect of drawn-out, unnecessarily inflated interest rate payments, hospitals were forced to pay millions of dollars to terminate these unsuccessful bets on the direction of interest rates (Dugan 2010; McDaniels 2013). Even if hospitals escaped having to pay staggering fees to cancel their swaps, many still suffered from having to allocate a sizable portion of their cash reserves to collateral for the swaps (Walker and The Baltimore Sun 2013; Evans 2010). After this experience, many hospital systems retreated from the use of interest-rate securities.

Auction rate securities (ARSs) were another financial instrument used by hospitals to manage interest on their long-term debt. ARSs became widely used among hospitals; by 2007, the market for ARSs was estimated to be as high as $330 billion. They were particularly attractive for hospitals because they allowed for the financing of long-term debt with short-term interest rates, and in many instances, broker-dealers touted ARSs as being nearly risk-free and highly liquid. In the end, the opposite proved to be true. ARS’ uniqueness lay in regular intervals whereby hospitals’ interest rates would be reset by Dutch auction, essentially creating floating rates. (D’Silva, Gregg, and Marshall 2008). Investment banks promised to be a buyer of last resort, preventing a failure in the market.

ARS bonds earned banks more than $1 billion in fees at the initial sale plus annual payments for handling the auctions of a quarter percentage point, or about $650 million a year (Stewart and Smith 2012). Later, Citigroup and UBS were investigated for misleading nonprofit hospitals. ARS made up a significant portion of many hospitals’ long-term debt (Stewart and Smith 2012).

For a period of time, ARSs functioned well for hospitals. But this ended in 2008 with the downgrading of financial institutions amid the housing and financial crisis. A loss of faith in the willingness of financial institutions to back the auctions led to high failure rates of the auctions. The investment banks that promised to be lenders of last resort backed out, citing strain from the ongoing financial crisis and mortgage lending defaults (Greene 2008). The failure of the ARS market had a drastic and scarring impact on hospitals from coast to coast, forcing hospitals to backtrack on intentions to build new facilities (Dugan 2010).

More recently, nonprofit hospital systems avoided derivatives, preferring to refinance municipal bonds if interest rates fall. But this strategy was closed off by the 2017 Trump Administration’s Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) which ruled out advance refunding of municipal bonds. Hospitals were no longer able to take advantage of a fall in interest rates (Stewart and Owhoso 2004; Rose 2012; Bannow 2019; Franklin 2020).

Tax-free municipal bonds remain an important source of funds for construction, expansion, renovation, and modernization of hospital facilities. But hospitals are more cautious in managing their debt.

While raising investment funds in capital markets proved challenging for nonprofit hospitals, the cost-plus payment arrangements by Medicare and Medicaid for reimbursing the costs of caring for eligible seniors was a boon to all hospitals. It insulated them from the vagaries of demand for hospital services and provided a buffer of reliable payments for care of a significant share of their patient populations.

But cost-plus payments also meant a lack of constraints on pricing for doctor and hospital services. Prices for procedures varied widely and health care costs trended up. This arrangement began to come under pressure in the late 1970s and early 1980s as the inflation rate began rising more steeply and medical fees increased rapidly. This began to threaten the solvency of the Medicare program. That caught the attention of Congressional policymakers and focused attention on health care prices. A number of modest measures intended to slow the rate of health care inflation were adopted but had little effect (Mayes and Berenson 2006). Bolder action would be needed to secure the solvency of Medicare.3

In 1983, Congress made drastic changes in the way that Medicare reimbursed hospitals. Instead of reimbursing hospitals on a cost-plus basis for every service the patient receives (fee-for-service payments that covered separate charges for doctors’ services, lab tests, procedures, and hospital stays), Medicare instituted a “prospective payment” system. Under this system, hospitals received a predetermined payment for treating Medicare patients depending on their particular diagnosis, referred to as diagnostically related groups or DRGs (Mayes and Berenson 2006). This change in payments to hospitals did not apply to Medicaid, which continued to use either a fee-for-service payment model or, more commonly, a Managed Care Plan (capitated payments made on a per-enrolled person in the plan) to pay for Medicaid benefits (Scott 1984).

The introduction of Medicare Severity Diagnostic Related Groups (MS-DRGs) as the basis for reimbursements for procedures and stays at acute care hospitals marked Medicare’s transition from a cost-plus reimbursement model to a prospective payments model. In this payment model, Medicare prospectively sets the rates hospitals receive for most services. If a patient can be treated at a lower cost, as a result of fewer tests or a shorter hospital stay, for example, the hospital keeps the difference. If the cost of treating a patient exceeds the Medicare payment, the hospital absorbs the extra costs (Mayes and Berenson 2006).

Medicare provides a clear description of prospective payments to hospitals for operating costs and capital costs in its online publication MLN Educational Tool/Medicare Payment Plans (2024). In-patient hospital discharges are examined and assigned to the appropriate MS-DRG category. This takes into account the severity of the patient’s illness, complexity of service, and consumption of hospital resources as well as diagnoses (up to 25), procedures performed (up to 25), sex, age, and discharge status.

Hospitals receive operating and cost-of-capital payments based on patients’ MS-DRG status. Operating costs cover labor and supplies, while capital-related costs cover depreciation, interest, rent, and property-related insurance and taxes. Payment rates are adjusted annually to reflect (1) any changes in treatment costs compared to average Medicare treatment costs and (2) any changes in local market conditions compared to national conditions (e.g., wage rates).

The changes in how hospitals are paid put a premium on hospitals’ ability to control costs related to purchasing, inventory, staffing, and scheduling. Hospital administrators also encouraged doctors to reduce the length of patient stays and move patient care outside of hospitals to facilities (out-patient surgery center, skilled nursing facilities) that had lower costs. At the time prospective payments were first introduced, outpatient care received more generous Medicare reimbursements (Mayes and Berenson 2006). Medicare responded to pressures to curb the growth of payments for MS-DRGs by ratcheting down the annual increases. By 1989, the growth in Medicare expenditures had fallen to just 1 percent a year. This improvement for Medicare translated into a substantial decline in hospital Medicare operating margins and, for some hospitals, including academic medical centers, overall operating margins declined (Henderson 2015).

Leaving financing of construction, modernization, and expansion to the tender mercies of financial markets has led to unequal funding for capital investments and unequal quality of hospitals’ physical plants. In both the original Medicare cost-plus reimbursement model and in the MS-DRG model, bigger and better-endowed hospital systems receive larger payments than smaller or poorer hospitals by virtue of having higher depreciation, interest, and other property-related payments. These payments act as subsidies to the hospitals that facilitate the issuance of tax-free municipal bonds and other borrowing in capital markets, disadvantaging smaller and poorer hospitals. The result is a two-tier hospital system with poor and/or uninsured or underinsured patients more likely to be treated in hospitals with an inferior physical plant, outdated technology, and fewer specialists. A lack of resources and physical capacity may lead these hospitals to triage patients out of necessity, treating those more likely to recover and paying less attention to those with more acute health problems.

For-profit hospitals did not begin to be a serious presence in health care until 1965 and the establishment of Medicare and Medicaid. We noted briefly that Medicare provided reimbursements to for-profit as well as nonprofit hospitals and health systems. Unlike philanthropic donations or Hill-Burton payments for capital investments, Medicare payments subsidized the upgrading of facilities by covering costs associated with capital investments. Funds to cover the actual cost of construction and modernization of hospital facilities would have to be borrowed from financial markets.

Medicare reimbursements to for-profit providers were more generous than reimbursements to nonprofit or public (government-owned) hospitals. Medicare paid for-profits a premium based on the logic that they needed additional capital payments to provide a return on shareholders’ investments. This “virtually guaranteed for-profit facilities a ‘risk-free’ investment return” (Jeurissen et al. 2021:71). For-profit hospitals also benefited from government reimbursements for their interest payments on debt from buying up additional hospitals, while tax laws permitted them to claim accelerated depreciation. With higher relative government subsidies, the for-profit chains grew at a faster rate than nonprofit hospitals, and their share of hospital beds doubled to 9 percent by the early 1980s (Jeurissen et al. 2021: 71).

This method of subsidizing hospitals had three negative outcomes that continue to plague the US health care system to this day (Grogan 2023).

The IRS was complicit in the development of a two-tier health system, having issued the regulation in 1969 that changed the definition of charity as discussed above (IRS 1969). No longer did nonprofit hospitals have to treat indigent patients to qualify for nonprofit tax status with its exemption from most income, property, and sales taxes. Health education for local communities, financial support for the education and training of medical residents, and the shortfall in Medicaid payments for procedures compared to Medicare payments, among other activities, now counted as charitable contributions.

Over the past two decades, Academic Medical Centers (AMCs) went from being on the verge of financial crisis to being the most financially stable type of nonprofit hospital. This transformation is in large part due to shifts in IRS guidelines which opened the door for nonprofit hospitals to retain tax-exempt status without caring for indigent patients and, later, to pocket profits from for-profit subsidiaries tax-free and to form partnerships with Silicon Valley venture capital firms.

AMCs are hospitals that provide patient care, educate health care providers in partnership with at least one medical school, and have a capacity for research and development of products and processes that improve patient health. AMCs have the capacity to treat the most complex health cases and to provide the highest quality medical care. They also tend to treat a wealthier and whiter population than nearby safety-net hospitals in urban areas. There is evidence that uninsured and Medicaid patients, who are disproportionately racial and ethnic minorities (KFF 2022), face barriers to obtaining care at AMCs (Tikkanen et al. 2017; Acosta and Aguilar-Gaxiola 2014).

Hospital venture capital arms typically receive investment from or partner with Silicon Valley VC firms.4 Investments by these venture capital subsidiaries have increased substantially since 2010, with major increases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Total investments by the VC arms of major hospitals went from $284.53 million in 2010 to $2.7 billion in 2021, a tenfold increase (Pifer 2022).

Nonprofit hospital systems utilize a number of financial strategies to increase their nonoperating revenue in addition to venture capital investments. They held more than $283 billion in stocks, hedge funds, private equity, venture funds, and other investment assets in 2019 (Rau 2021). Only $19 billion, or 7 percent, of their total investments, were principally devoted to their nonprofit missions rather than producing income (Rau 2021). Where does this massive amount of nonoperating revenue come from? According to Becker’s Healthcare, at least 23 hospitals now have their own investment arms (Diaz 2023). The number of dollars funneled into venture activity by large hospitals in recent years dramatically outpaces what it was a decade ago (Figure 2 in Pifer 2022). Annual venture funding round activity in 2020 was $807.41 million for Kaiser Permanente Ventures (five times its 2010 investment), $626.6 million for Ascension Ventures (five times its 2010 investment), and $269.6 million for Mayo Clinic Ventures (three times its 2011 investment) (Pifer 2022).

Across the whole health care industry, recent top priorities of venture capital are to invest in health care data infrastructure providing software, hardware, or advisory services in the space (Balasubramanian 2023), as well as digital health, mobile health, health information technology, wearable devices, telehealth and telemedicine, and personalized medicine (Gondi and Song 2019). For example, the value of investments in digital health increased by 858 percent between 2010 and 2017, outdoing the 166 percent growth in total venture capital funding in the overall economy (Gondi and Song 2019). The pandemic certainly spurred investment in this area as well as in hospitals as health systems ramped up their virtual communications (Pifer 2022). As technology’s presence in health care continues to increase, venture capital firms will be there. Hospitals are not just the customers of new venture capital-led innovations but many are major investors, contributing their own funds.

Nonprofit hospitals are granted an exemption from paying taxes in exchange for promoting health and providing free or below-cost care to those unable to pay. Free care for indigent patients has been a basic tenet of charitable hospitals for centuries and has long been the basis for the tax exemption enjoyed by today’s nonprofit hospitals. A 1956 IRS standard said hospitals had to be “operated to the extent of [their] financial ability for those not able to pay for the services rendered and not exclusively for those who are able and expected to pay” (Rev. Rul. 56-185, 1956-1 C.B. 202). Essentially, charity care for uninsured or underinsured was required for hospitals to receive an exemption from paying taxes.

This established tax-exemption definition was drastically changed by a 1969 IRS revenue rule (C.B. 117. Revenue Ruling 69-545),5 which removed the stipulation that providing charity care for the poor was the only way to satisfy the tax-exemption requirement. The definition of charity care was broadened. Now hospitals were able to provide vaguely defined community benefits to retain their tax-exempt status: “A nonprofit hospital must be organized and operated exclusively in furtherance of some purpose considered ‘charitable’ in the generally accepted legal sense of that term, and the hospital may not be operated, directly or indirectly, for the benefit of private interests” (C.B. 117. Revenue Ruling 69-545, page 2). Ambiguous language left open an important question: was it now a condition of tax exemption that a hospital accept patients covered by Medicaid and Medicare? (Fox and Schaffer 1991, 258). Although a hospital was no longer required to provide charity care, the IRS said it considers doing so to be a significant factor indicating community benefit (GAO 2023). The change was a sharp turn from the centuries-old definition (Fox and Schaffer 1991). Fox and Schaffer (1991) argue that the 1969 rule made it easier for hospitals to refuse to treat Medicaid and uninsured patients.

As a result of the 1969 IRS ruling, hospitals can satisfy the community benefit requirement by paying for health promotion activities. Some nonprofit hospitals have interpreted this to include absorbing payment-cost differentials from public programs, community health improvement services, and operations, health professionals’ education, and research (IRS Schedule H 990 2023). The majority of community benefit spending still goes to uncompensated care (Young et al. 2013), but health-promoting activities and investments are a growing share.

The 1969 IRS rule did not establish a mechanism to check on whether hospitals are actually providing benefits to the community. The IRS does not have the authority to mandate these activities and federal law does not say how much and what type of community benefit hospitals have to provide; that power resides with Congress. Between 1969 and 1989, no hospital lost its tax-exempt status for failing to provide free emergency room care or serve Medicaid patients as the IRS had no program in place to monitor compliance. Finally, in 1985, Congress passed legislation – called the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act6 – that required tax-exempt hospitals to provide emergency medical services regardless of the patient’s ability to pay. Furthermore, the IRS ruled that providing emergency services plus the acceptance of Medicaid patients were required to demonstrate charity care (Fox and Schaffer 1991:253-274).

Today, the IRS has six different factors that can satisfy the community benefit needed to maintain tax exemption (GAO 2023):

The Affordable Care Act set three further requirements for hospitals:

Nonprofit, tax-exempt hospitals are only reviewed by the IRS once every three years and have the flexibility to determine what counts as charity care and even how much they undertake to contribute to the community (GAO 2023). This ultimately means that nonprofit hospitals are technically only supposed to be sanctioned if they refuse to treat Medicaid patients or uninsured people experiencing an emergency medical situation (Fox and Schaffer 1991: 351-2). But in reality, the IRS does not follow through on sanctioning these hospitals nor does it have an organized, consistent data collection system. In a recent report, the Government Accountability Office analyzed 2020 IRS data and found 30 nonprofit hospitals that got tax breaks in 2016 despite reporting no spending on community benefits (GAO 2023).

The Kaiser Family Foundation estimated the total tax exemption for all nonprofit hospitals (including federal, state, and local taxation) was $28 billion in 2020 (Godwin, Levinson, and Hulver 2023). Federal tax exemption accounts for about half of this ($14.4 billion) while state and local tax exemption was $13.7 billion. Most nonprofit hospitals aren’t required to pay state or local sales taxes, local property taxes, or state corporate income taxes. However, there is some variation as states attempt to hold the hospitals accountable (Godwin, Levinson, and Hulver 2023).

The Lown Institute, a health care think tank, compared 1,700 nonprofit hospital systems’ spending on financial assistance and community investment to the estimated value of their tax exemption. This “fair share spending” measure puts a value on how much nonprofit hospitals are actually giving back to their communities. The report found that in 2023, 77 percent of hospitals spent less on actual care for the poor and community health investment than the estimated value of their tax breaks (Miller 2024).

Recent reporting indicates that some of the most profitable hospital markets in the country have the highest levels of patient debt (Levey 2022). Medical debt can be very high even in hospital systems that are thriving with large total margins, which begs the question of whether nonprofit hospitals are spending anywhere close to the value of their tax breaks. This charity care is vital for underinsured and uninsured people who bear a substantial part of the burden of medical debt. While the amount spent on charity care varies widely across hospitals, half of all hospitals reported that the cost of charity care represented just 1.4 percent or less of operating expenses in 2020 (Levinson, Hulver, and Neuman 2022). Additionally, research indicates that for-profit hospitals are spending just as much or more on charity care as nonprofit hospitals (as a percent of total expenses) despite the large tax breaks nonprofits receive (Bruch and Bellamy 2021).

There are a number of states modeling what federal legislative action can be taken to hold nonprofit tax-exempt hospitals accountable. We discuss the following two important case studies of Cleveland Clinic and UPMC.

When Congress passed the Balanced Budget Act in 1997, funding for nonprofit hospitals was cut so Medicare could rein in federal health care expenditures (Bazzoli et al. 2004-05). AMCs were among the recipients of this cut. The Act included large reductions in federal hospital payments (Appelbaum and Batt 2021) which reduced the revenue for hospitals that relied on Medicare reimbursements for patient care as a significant share of their income. At the same time, AMCs were also facing growing competition from large, consolidated hospital systems capable of treating mid- and high-acuity patients at lower costs.

As AMCs were struggling financially, a new possibility to raise revenue came along in 1998. An IRS ruling (Rev. Rul. 98-15) allowed nonprofit hospitals to own for-profit subsidiaries and pay no taxes on profits earned by these subsidiaries. This was an invitation for venture capital firms to partner with AMCs and other large nonprofit hospitals with a demonstrated research capability (e.g., Kaiser Permanente, Sutter Health, CommonSpirit) to develop patentable products and processes (Appelbaum and Batt 2021). The rule made it possible for nonprofit hospitals to benefit from the business activities of for-profit subsidiaries or joint ventures without paying taxes on the profit. The IRS permitted this type of alliance out of an initial concern that it was needed for AMCs to stay financially stable. Over time, however, it further enriched some of the most financially successful hospitals, exacerbating inequalities in access to resources for capital improvements and expansion. The advantages of nurturing start-ups whose profits are accrued tax-free by their AMC and Silicon Valley owners resulted in an explosive increase in investment income7 and CEO pay for the nonprofit hospitals (Liss 2019; Table 1 in Section 6 of this paper).

The large investment income of AMCs has enabled them to recruit the most skilled specialists in every field, to invest in state of the art technology, and in some cases to offer patients near luxury hotel accommodations and services. But oftentimes residents of the very poorest areas of the city with high rates of chronic disease and other health problems are unable to access AMC care, even if they live near the hospital, because it is not an emergency and they lack insurance coverage the AMC accepts. AMCs’ large nonoperating revenues have also fueled the consolidation of hospitals and health systems as these health systems have sufficient resources and/or access to borrowed funds to acquire other health providers.

When for-profit subsidiaries grow large enough to threaten the hospital’s nonprofit status, they can be spun out as for-profit, tax-paying corporations in which the hospital is a major shareholder. As a shareholder, the hospital will receive dividends. This is passive income on which the hospital is not required to pay taxes.