April 27, 2017

Dean Baker, Rebecca Vallas, Katherine Gallagher Robbins, and Rachel West have already pointed out most of the problems with Washington Post’s recent story and its subsequent editorial on Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). But I want to say a bit more about one aspect of how the Post’s framing of the story, and use of cherry-picked data, paints a misleading picture for the public.

The Post tells the story of a 39-year-old man living in a small Alabama town who is deciding whether to apply for SSDI. The accompanying data hypes two things: the increase in the number of people ages 18-64 receiving disability benefits since 1996 and the disability beneficiary rates by county since 2004. (As West and Gallagher Robbins found, the Post made several errors in their analysis, some of which they corrected, but the data errors aren’t my focus here). The editorial cites the initial story, links SSDI to the declining labor force participation (LFP) of prime-age men, and calls for cutting SSDI to “make sure work pays for all who are willing to work.”

The story and the editorial are only the most recent of elite national media pieces promoting the idea that SSDI is a de facto unemployment assistance program for prime-age men who may be “desperate” but aren’t really disabled. Reading these stories, I imagine many readers come away with the impression there has been a large increase in the number of 30- and 40-something men who are receiving disability benefits, and that this is driving a large part of the decline in prime-age men’s labor force participation over the last two decades.

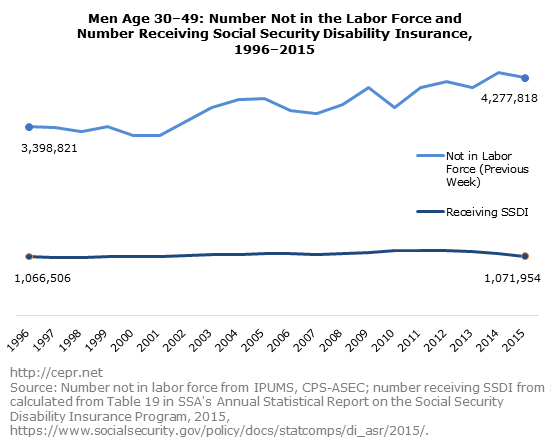

The figure below shows the number of men ages 30-49 who were not in the labor force in the week before they were surveyed and the number receiving Social Security Disability Insurance. The potential SSDI applicant the Post chose to profile is in the very middle of this age range. It’s also the same age range that AEI’s Charles Murray focused on in his book Coming Apart, consisting of, as he put it, “adults in the prime of life, with their educations usually completed, engaged in careers and raising families.” The time range in the figure, 1996 to 2015, is the same one the Post uses to estimate the national increase in working-age adults receiving disability benefits.

As the figure shows, the number of men in this age range who were not in the labor force increased by about 900,000 between 1996 and 2015, but there was hardly any increase in the number of such men receiving SSDI (about 5,500 or 0.5 percent). In short, there’s not much reason to think SSDI is a significant driver of the decline in the labor force participation of 39-year-old men like the one the Post seemed to think was representative.

What about Supplemental Security Income (SSI), a means-tested benefit for people with disabilities who have very limited or no capacity to work? The earliest SSI data by age and sex I could find on the SSA site are for 1999, so it’s not exactly comparable, but still quite close. As the table below shows, the number of men ages 30-49 receiving SSI was slightly lower in 2015 than in 1999.

Men Age 30-49

|

Year |

Not in Labor Force |

SSDI |

SSI |

|

1996 (1999 for SSI) |

3,398,821 |

1,066,506 |

749,286 |

|

2015 |

4,277,818 |

1,071,954 |

737,655 |

|

Difference: 2000-2015 (1999-2015 for SSI) |

878,997 |

5,448 |

-11,631 |

|

Percentage Difference |

26% |

.5% |

-.2% |

Source: Number not in labor force and SSDI, see figure above; SSI figures are calculated from Table 7.E3 in SSA, Annual Statistical Supplements for 2000 and 2016, https://www.socialsecurity.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2016/

There are other disability related benefits, mostly notably workers’ compensation and veterans’ disability compensation. The number of prime-age workers receiving workers’ compensation is certainly down since 2000, while the number receiving veterans’ compensation is up. But most prime-age workers receiving these benefits are in the labor force, not out of it.

In short, a newspaper that leaves readers with the impression that disability benefits are serving as an unemployment program for middle-aged men who are desperate, but not disabled, is doing its readers a grave disservice.

So why are fewer prime-age men in the labor force today than in 2000? Labor demand is a big part of the story. As Dean Baker pointed out in his earlier commentary on the Post’s article, “the most obvious way to increase employment for prime-age workers is to deal with the demand side of the story. For example, it might be a good idea if the Fed stopped trying to slow the economy by raising interest rates.”

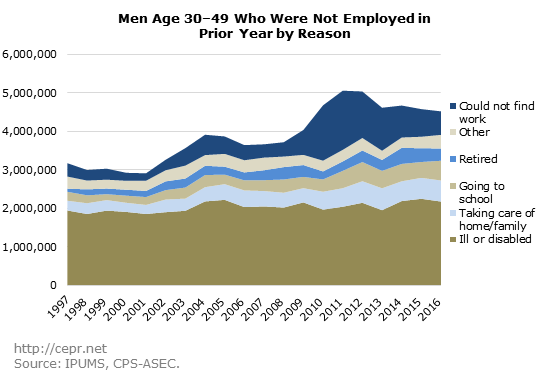

It’s also interesting to look at the reasons men give for not working in the previous year. The figure below charts the number of men ages 30-49 who were not employed in the previous year, by reason. In percentage terms, some of the largest increases are for taking care of home/family and going to school (both up by over 100 percent), compared to only a 12 percent increase in those who are ill or disabled. The percentage who report not being able to find work was about 76 percent higher in 2016 than in 1997, although it is much more cyclical than the others.

There are many working-class men and women, including the one the Post profiled, who deserve a much better deal than they’ve been getting from policymakers. But their plight has nothing to do with Social Security and related disability benefits. If policymakers want to help them, they should adopt policies that would improve the compensation and quality of working-class jobs. Policymakers should also reform programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit and Temporary Assistance in ways that help more struggling middle-aged people regardless of whether they have minor children in the home.