February 09, 2012

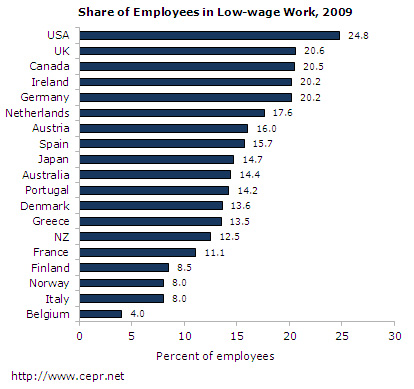

As I write in a new CEPR briefing paper (pdf), the United States leads the wealthy world in the share of its workforce in low-wage jobs. According to the commonly used international definition of low-wage work –earning less than two-thirds of the median hourly wage– about one-fourth of US workers are low-wage.

The report draws five lessons from the experience of the United States and other rich countries over the last several decades:

- Lesson 1: Economic Growth is not a Solution to the Problem of Low-wage Work

- Lesson 2: More “Inclusive” Labor-market Institutions Lead to Lower Levels of Low-wage Work

- Lesson 3: The United States is a Poor Model for Combating Low-wage Work

- Lesson 4: Low-wage Work is Not a Clear-cut Stepping Stone to Higher-wage Work

- Lesson 5: In the United States, Low Wages are among the Least of the Problems Facing Low-wage Workers

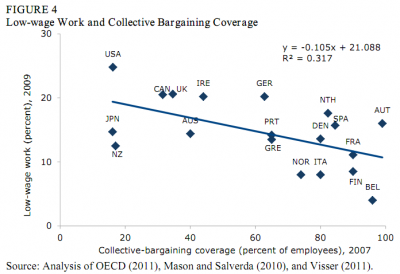

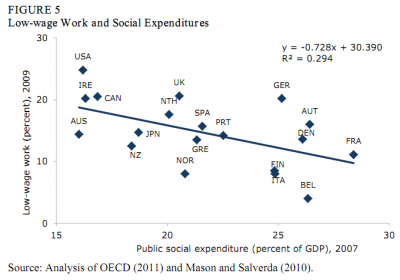

The countries that have been most successful in reducing the share of their population in low-wage work have typically done so by having widespread collective bargaining or by funding a reasonable and reliable safety net (which, among other things, raises the bargaining power of low-wage workers). See, for example, Figures 4 and 5 from the paper:

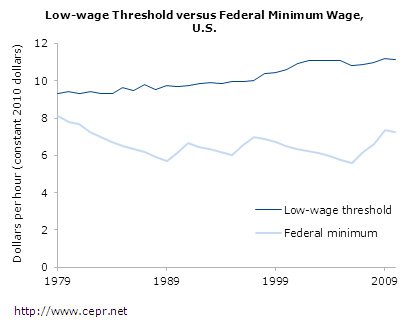

The United States, meanwhile, has relied primarily on the minimum wage and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Both could dramatically reduce the share of the workforce on low pay (see, for example, this excellent paper by Jeannette Wicks-Lim and Jeffrey Thompson), but the US minimum wage and EITC have both been set too low to have a meaningful impact on low-wage work. This figure, for example, shows the gap between the low-wage threshold (what a worker would have to earn to rise above “low-pay”) and the federal minimum wage, in each year from 1979 through 2010.

But as the paper also emphasizes, low-pay isn’t even the worst of it. Low-wage workers are also much less likely to have health insurance (of any kind, employer-provided or from other sources), paid sick days, paid parental leave, or paid vacation. Not to mention very little in the way of job security.

This post originally appeared on John Schmitt’s blog, No Apparent Motive.