July 25, 2017

Binyamin Appelbaum had an interesting discussion of inflation in the NYT yesterday. As he notes, it has been below the Fed’s target throughout the recovery and, contrary to expectations, it has been falling in recent months. This suggests that the economy could be operating at a higher level of output with more employment. That would put more upward pressure on wages and lead to somewhat higher inflation. That suggests that the Fed may have been wrong in its recent interest rates hikes which were intended to slow growth.

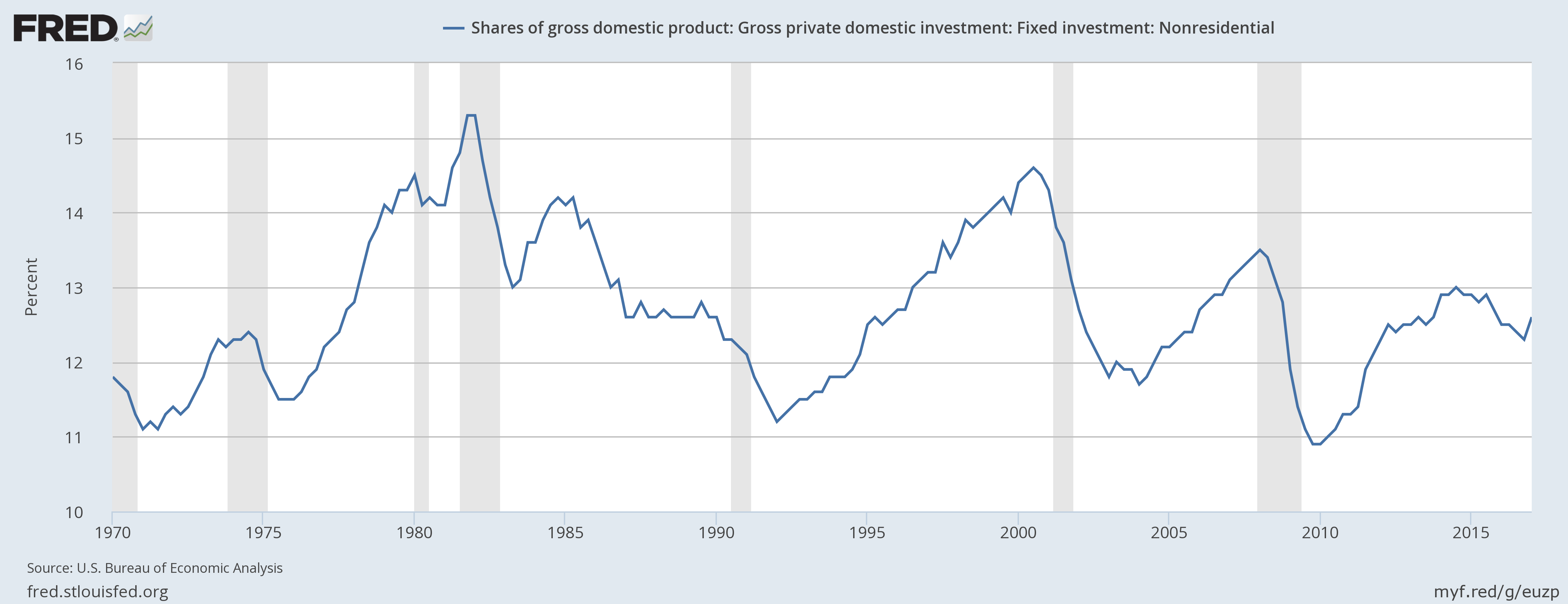

There are a few other points worth noting about inflation while we are on the topic. While it is common to say that inflation hurts investment, at least in the U.S. this does not appear to have been the case.

As can be seen the investment share of GDP peaked in the late 1970s and early 1980s when inflation was also running at its most rapid pace in the post-World War II era. Investment has been considerably lower as a share of GDP in the last three decades of moderate inflation. The one exception when investment got close to its peak of the high inflation era was at the end of the 1990s during the stock bubble.

While it would probably be wrong to say that the high inflation of the late 1970s and early 1980s was the cause of high investment, it seems difficult to make the case that it was a serious impediment to investment. It is also worth noting that we saw inflation that crossed into the double-digits in those years. If that pace of inflation didn’t slow investment, it is difficult to believe that a modest increase in the inflation rate in the current period, say to 3 or 4 percent, could have a negative impact on investment.

One reason inflation accelerated quickly in that era was that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) had an error in housing component that caused it to overstate the annual rate of inflation by as much as 2.0 percentage points. At a time when many contracts were indexed to the CPI, this error in measurement was passed on in the form of higher wages, rents, and other prices.

Flipping the issue over, there remains considerable confusion about the potential problems of deflation. First of all, back at the bottom of the recession, there was concern about the risk of a deflationary spiral. The idea was that deflation would discourage investment and consumption. This would lead to less demand, which would mean more downward pressure on prices. There are several reasons this problem did not arise.

First, wages are sticky downward. This means that we never saw substantial declines in nominal wages. This was true even in Japan, which did have several years of deflation. There was no real tendency for the rate of deflation to increase, with deflation peaking at roughly -1.0 percent.

However, the concern about delayed purchases due to falling prices is also misplaced. It is important to remember that the inflation indexes are averages. Some prices increase more rapidly and some less rapidly than the overall index. When the inflation rate is very low it means that many prices are falling. If the inflation rate tips from being just above zero to just below zero it only means that the percentage of items with falling prices has risen. That hardly seems like a disaster story.

Furthermore, it is important to remember that these are quality-adjusted prices. Many consumers may fail to recognize quality improvements in the same way as the statistical agencies. For years, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) was reporting the price of computers falling by more than 30 percent annually even as the price of a new computer was little changed one year to the next. The reason for the difference was that BLS was picking up huge rates of quality change. If consumers did not recognize these quality improvements, they would see an item that was changing little in price, rather than one where the price was falling by 30 percent every year.

Again, it is difficult to see how the economy can somehow face a serious problem if its computers and the quality of other items are improving year-by-year, compared with a situation where they are not. But this would be the case if we took deflation concerns very seriously.

Comments