May 02, 2014

I agree with everything Dean Baker has to say in his post on the NYT article on changes in living standards of low-income people, but have a few additional thoughts.

Reporter Annie Lowrey is mostly right to say that: “despite improved living standards, the poor have fallen further behind the middle class and the affluent in both income and consumption.” But she’s on less firm ground when she says “two broad trends account for much of the change in poor families’ consumption over the past generation: federal programs and falling prices.”

First on “federal programs”, the biggest source of income for low-income people is market income, not transfers. For example, as this EPI analysis of CBO’s comprehensive income data shows, about 56 percent of the income of households in the bottom quintile comes from wages and self-employment income. By comparison, only about 20 percent comes from cash transfers and 15 percent from in-kind income (a category that includes food stamps and public health insurance). So, ultimately, market income and the political decisions that shape the distribution of market income are the most important factors affecting low-income people’s consumption. If, as Dean notes, we had made trade and other macroeconomic policy decisions that increased the number of good jobs available to poorly compensated and unemployed workers, the income of both the working and middle classes would have not fallen so far behind that of the affluent.

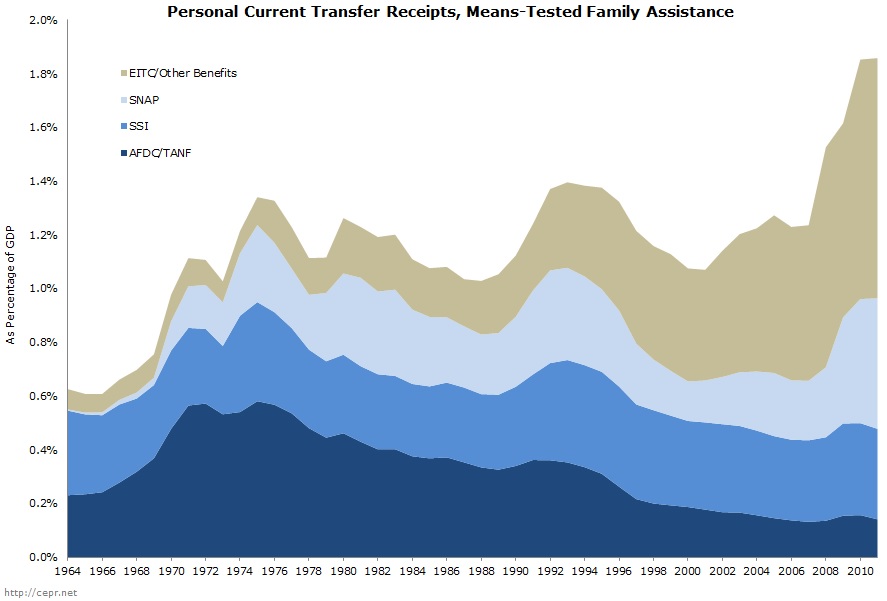

A related point here is that the nature of spending on the programs that folks like Robert Rector and Paul Ryan rail against has changed in pretty fundamental ways. The chart below shows spending on means-tested income supplement programs as a percentage of GDP since 1964, when President Johnson made his War on Poverty declaration.

Although it’s easy to get the impression that anti-poverty programs were invented in the 1960s along with sex, drugs, and rock and roll, as this chart shows we were spending about .6 percent of GDP on means-tested income support programs before Johnson’s declaration. That spending increased to about 1.3 percent of GDP in 1975-76, and then rose to just over 1.8 percent during the Great Recession period. But the most interesting thing about the trend since the mid-1970s is how much it has shifted to from benefits widely perceived to be “unearned” (AFDC/SSI/food stamps) to the EITC, which is directly linked to earnings as well as policies like the minimum wage, labor law, and trade. The expansion of the EITC that has taken place over the last several decades has made poorly compensated workers better of than they would have been in it’s absence, but it doesn’t change the fact that those would be even better off if we hadn’t let the value of the minimum wage decline in real terms or made it easier to employers to drive down union density.

Contrary to the dependency rhetoric of Ryan and Rector, the trend in spending on food stamps, SSI, and AFDC/TANF combined has been steadily downward since 1975, although there have been temporary increases during recessions.

On Lowrey’s second trend, “falling prices”, we haven’t had deflation over the last generation, so aggregate prices have risen not fallen. And, while the prices of much of the “stuff” that one can buy at places like Wal-Mart have declined, most other costs, as Lowrey goes on to note, have not. One thing I would add here is the importance of housing and transportation for low-income families. These two items account for 55 percent of consumption expenditures by households in the bottom income quintile and 64 percent of expenditures by those in the second quintile. Moreover, transportation has grown as a share of family budgets in recent decades, going from 14.7 percent of the average family’s budget in 1960 to 19 percent in 2002-2003. In fact, the average low-income family today spends as much of its budget on transportation as it does on food. Trends like sprawl likely play an important role here. Hopefully, Lowrey will take a closer look at issues like this in the future.