July 17, 2019

July 18, 2019

Sen. Elizabeth Warren

Hart Senate Office Building, 317

Washington, DC 20510

Re: Stop Wall Street Looting Act

Dear Senator Warren,

I am writing regarding your proposed Stop Wall Street Looting Act which would prevent private funds from imposing all the costs of their risky investments on investors, workers, and communities while profiting from all the gains. Private equity investments are exploding — the net asset value has septupled since 2007 and the value of new private equity deals in 2018 was $1.4 trillion, surpassing the pre-crisis peak.[1] Americans in every community are affected by the industry — today, more than 11 million people are employed by private equity-owned businesses and millions more have their pensions invested in private funds.

Over the last decade, an increasing number of private equity and other private funds have taken controlling interests in hundreds of viable companies, using their assets to secure unsustainable loads of debt, and then stripping them of their wealth, preventing them from investing in the products and people that will allow the companies to thrive in the future. The funds charge investors high fees without providing them visibility or control into their activities and feed a growing market for risky corporate debt that is reaching dangerous levels. Your proposal would address the worst abuses of this business model while preserving productive investments by requiring PE firms to face accountability for their management decisions, limiting their ability to loot the companies they take over, empowering investors to fully understand private equity and other private funds, and protecting workers, customers, and other stakeholders or businesses across the country.

The Leveraged Buyout Model

Leveraged buyouts are a central feature of the private equity business model, but have also been used by hedge funds (ESL and Sears) and real estate investment trusts (Vornado and Toys ‘R Us). In a leveraged buyout, a private equity firm sponsors an investment fund that acquires a target company for its portfolio using capital supplied by investors as the down payment or equity contribution to the deal. It finances the balance of the purchase using large amounts of debt (“leverage”) that the acquired company — not the PE firm or the PE investment fund — is responsible to repay. The PE firm, via the General Partner (a committee of principals in the PE firm), contributes very little to the transaction — typically 2 cents to the private equity fund for every dollar contributed by the Limited Partner investors, which are pension funds, endowments, sovereign wealth funds, and wealthy individuals. For example, if a private fund finances the acquisition of the target company with 50 percent debt, the private equity firm has just 1 percent (.02*.5 = .01) of the purchase price of the business at risk.

Thus, the PE firm is playing with other people’s money while facing little accountability for its decisions. Despite putting up only 2 percent of the equity used to purchase the target company for its PE fund’s portfolio, the PE firm typically collects 20 percent of any profit from the subsequent resale of the company. Debt boosts returns from a successful exit from the company. Meanwhile, through fees and other forms of asset stripping, PE firms drain value from target companies, hurting their workforce, customers, suppliers, and creditors and forcing cuts to research, training, and other important investments that facilitate long-term success for a company and its stakeholders. With little to lose, but much to gain by loading the target company with debt, the PE firm is in a low risk, high return situation. A high debt burden puts the target company, its employees and its creditors at increased risk of bankruptcy.[2]

Your bill would align the incentives of the PE firm and the target company by requiring the PE firms to share liability with the target company for debt. PE funds will still make money from deals that provide investment in target companies that allows them to grow and thrive, but deals that rely on financial engineering and aggressive asset stripping of companies will no longer be viable. This critical reform will end the most abusive practices of the industry while preserving economically valuable transactions.

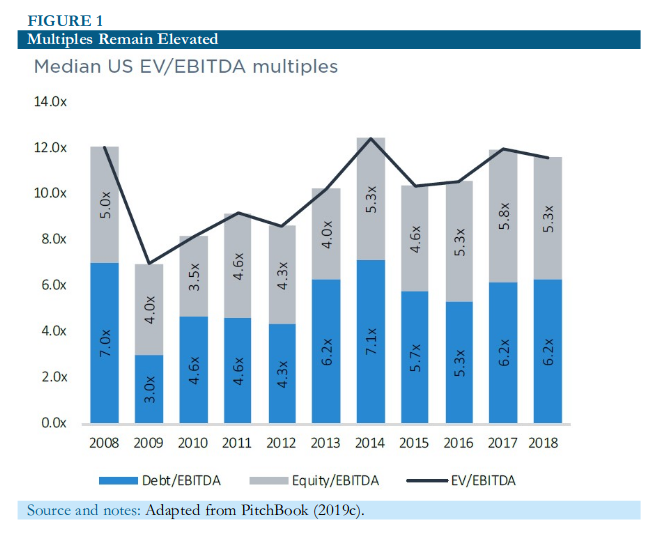

Financial Leverage Is In Record High Territory

During the 2008–09 financial crisis, highly leveraged firms experienced a disproportionate share of bankruptcies.[3] In March 2013, banking regulators made clear their concerns that debt in excess of 6 times company earnings increased the risk of bankruptcy to unacceptably high levels[4]. Leverage declined during and in the immediate aftermath of the crisis, but as we see in Figure 1, it soon began rising to high levels again. [5]

One way to observe this trajectory is by looking at the median price paid to acquire a company in a given year. Half of the deals for companies are priced above the median price, and half are priced below. As can be seen in Figure 1 (blue section of the bar graph), debt on the median-priced company was 7X EBITDA in 2008, fell to between 3 and 4.6 X EBITDA in 2009 to 2012, reached 7.1X in 2014, and was 6.2X in both 2017 and 2018. It rose to 6.96 in the first quarter of 2019. These are very large amounts of debt loaded onto acquired companies. In 2017 and 2018 median prices paid to acquire them rose to 11.9X and 11.5X EBITDA, respectively. The proportion of deals priced above 10.0X EBITDA in 2018 was 61.4 percent, the highest share ever recorded. Looking forward, a pickup in high-priced transactions is likely as PE funds need to spend down high levels of “dry powder” — commitments from limited partners in the fund that have not yet been deployed.[6]

The leveraged lending market has grown rapidly — 20 percent in 2018 and now stands at $1.2 trillion, double its peak of $600 billion at the time of the financial crisis — which has drawn the attention of financial markets regulators. Comptroller of the Currency Joseph Otting, FDIC Chair Jelena McWilliams, and Federal Reserve Vice Chairman Randal Quarles — like doctors observing a slow-growing cancer — are in ‘watchful waiting’ mode as they try to determine whether this risky debt will grow to create systemic risk. They have acknowledged concerns about the increasing volume of leveraged loans. However, low interest rates in the years since the financial crisis have kept payments on corporate debt as a share of profits from spiking; a 2008-style financial crisis does not appear to be on the horizon.[7]

Still, high leverage poses a threat to target companies, investors and workers, even if it doesn’t yet threaten the financial system. The recent spate of bankruptcies, store closings, and even liquidations in what has been termed the ‘retail apocalypse’ makes it clear that a slowdown in the economy or a change in market dynamics as a result of a trade war or other disruption threatens the viability of highly leveraged firms, financial crisis or not. Private equity firms own only a fraction of U.S. retail chains, for example, but they are behind a disproportionate share—financial news service Debtwire calculates 40 percent[8]—of retail bankruptcies: Toys ‘R Us, Payless Shoes, Gymboree, Claire’s Stores, PetSmart, Radio Shack, Staples, Sports Authority, Shopko, The Limited, Charlotte Russe, Rue 21, Nine West, Aeropostale. PE funds also have major positions in other industries. Between 2011 and 2017, private funds bought more than 200,000 homes, mostly after foreclosure.[9] More than 1,500 small-city daily and weekly newspapers have been purchased by private equity,[10] as has the nation’s second largest nursing home chain.[11] The list goes on.

By aligning the interests of Wall Street investment funds with those of the Main Street businesses that produce and distribute goods and services, your proposal reduces the risky use of financial leverage by private equity and other investment funds and brings the debt of target companies into line with their business requirements. Your proposal also restores risk-retention requirements from the Dodd-Frank Act on corporate debt, requiring securitizers to have skin in the game so that they don’t make dangerous loans and immediately pass the risk on to unknowing investors.

Private Equity’s Extraction of Wealth from Portfolio Companies Disadvantages Workers and Creditors

PE firms often recoup their own outlay on the acquisition of a target company by a PE fund it sponsors within the first few years of owning it by requiring payments from the company. Many PE firms sign agreements with target companies that require the companies to pay monitoring and transaction fees. In 2018, 58.0 percent of private equity firms required their portfolio companies to pay them monitoring fees; 85.8 percent required payment of transactions fees.[12] These payments deplete resources that the companies could use to make competitive investments in technology and workers’ skills. The agreements lack transparency. Neither PE fund investors nor the company’s creditors know how much the PE firm is collecting.

In addition to paying fees, the funds may require a portfolio company to take on more debt by issuing junk bonds and using the proceeds to pay a dividend to its private equity owners — a so-called dividend recapitalization. It is not unusual for PE owners to pay themselves a dividend in the first year or two after acquiring a company. In a dividend recapitalization so large that it shocked even seasoned PE observers (who are used to a world where PE firms routinely extract large sums from their portfolio companies), Sycamore Partners had Staples, a company it acquired in 2017, refinance its debt in April 2019 and pay its PE owners a $1 billion dividend. In combination with a payment it took in January 2019, in less than two years Sycamore has extracted more than 80 percent of the equity its PE fund originally contributed to the deal.[13]

Sales of real estate or other portfolio company assets are another way private equity owners can extract wealth prior to a resale of the company. Proceeds of these sales repay any loans for which the asset was collateral. Typically, the asset sells for more than the loan, with the difference going to the portfolio company’s PE owners. The portfolio company now has to lease the real estate (or other assets) that it previously owned, and is saddled with rent payments. This differs from the sale-leaseback transaction in which the company gets the proceeds from the sale and can use the funds to improve business operations. In September 2006, Sun Capital Partners acquired Marsh Supermarkets, with 116 groceries and 154 convenience stores, in a leveraged buyout. Soon after it acquired the chain, Sun did a sale-leaseback deal for the real estate of many of Marsh’s stores, raising tens of millions of dollars for itself and obligating the supermarket stores to pay rent on locations they had previously owned. Sun also sold Marsh’s headquarters building and saddled the grocery company with a 20-year lease to 2026 at an annual rent of $2.8 million, scheduled to increase 7 percent five years later. In 2017, with just 44 stores remaining, Marsh went bankrupt.[14] While not all private equity sale-leaseback deals drive portfolio companies into bankruptcy, they do extract wealth and hollow out the companies, reducing their ability to make necessary investments to remain competitive.

Provisions of the Stop Wall Street Looting Act address the negative consequences of these transfers of resources from the portfolio company to its PE owners and protect the interests of the company and its workers both directly and indirectly. In addition to requiring PE firms to share liability for target firm obligations, your legislation confronts the most egregious looting by prohibiting dividend payments in the first two years post-acquisition, taxing private equity firms for the full value of the monitoring fees they charge, allowing creditors to claw back other transfers to the firm in bankruptcy, and ending the tax code’s favorable treatment of debt in highly leveraged companies. These steps to limit actions that strip value from target companies, regardless of their long-term success, would force private equity firms to focus on what they claim to prioritize in the first place—making improvements to the target firm’s business model to better position it for medium- and long-term growth, benefitting workers, customers, investors, and creditors in the process. The legislation would also end the federal policy that currently encourages companies to load up on risky, unsustainable levels of debt by allowing them to deduct interest on that debt from their taxes.

While a portfolio company’s PE owners may not wish it to become bankrupt and most PE deals do not involve bankruptcy, the PE firms often have little or no skin in the game after collecting these dividends and fees. The costs of bankruptcy are borne by the portfolio company, its workers and its creditors. Many provisions of the Stop Wall Street Looting Act protect the interests of workers and creditors in bankruptcy, while also reducing the incentives for PE owners to drive companies into bankruptcy in the first place, such as by extending liability for the portfolio company’s debt to the PE owners themselves. It would also ensure that workers receive legally required payments owed to them such as the 60 days’ pay and benefits required by the WARN Act in the event of a plant closing or mass layoff by making the PE firm jointly liable for those obligations. Under current law, workers do not receive these benefits if the portfolio company cannot afford the payments. Similarly, it holds the PE firm jointly liable with the bankrupt portfolio company for any pension obligations and severance payments.

Since the Financial Crisis, Private Equity Funds Have Failed to Beat the Stock Market

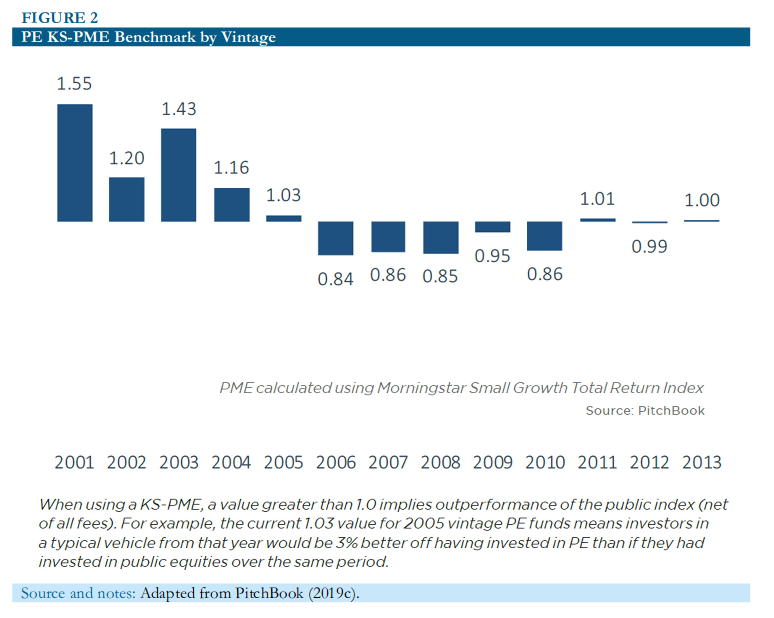

Private equity firms contend that their freewheeling behavior results in returns that beat the stock market by a wide margin and help fund retirees pensions. They caution against killing the goose that lays the golden eggs. This is an argument that might once have made sense, but no longer. Since 2006, the median private equity fund has just tracked the market.[15]

The internal rate of return (IRR), a widely used measure of fund performance and investor returns, has well-known flaws that make it easy to manipulate and inappropriate for this purpose. A major problem with the IRR is that distributions from a PE fund to investors made early in the life of the fund raises the IRR but not the financial returns an investor receives. For example, the sale of a highly successful portfolio company early in the lifespan of a PE fund, which is typically 10 years, can raise the fund’s IRR more than a sale of the same firm a few years later, even if would have brought a higher price if sold later. Similarly, dividend recapitalizations in the early years boost the fund’s IRR even if this transfer of resources to the PE owners weakens the company and leads later to a lower resale price. A higher IRR does not always mean higher returns to pension funds and other investors.

These well-known flaws led finance economists Steven Kaplan and Antoinette Schoar to develop an alternative method for calculating PE fund returns, the public market equivalent (PME). The PME compares returns from investing in PE with returns from comparable and comparably timed investments in the stock market, as measured by an appropriate stock market index. This measure better tracks the priorities of pension funds and other investors in private equity funds: their return by the end of the PE fund’s life span and how that return compares to the amount they would have earned in the stock market. A PME equal to 1 means that the return from investing in the buyout fund exactly matches the return from an equivalent investment in the stock market. A PME greater than 1 indicates that the return from investing in the PE fund was greater than the stock market return; a PME less than 1 means that the investor would have been better off in the stock market. A PME of 1.27, for example, means that the PE fund outperformed the stock market by 27% over the life of the fund. For a PE fund that lasts 10 years — the typical lifespan of PE funds — the cumulative outperformance implies an average annual outperformance just over 2.4%. The PME is the preferred metric of finance economists for evaluating fund performance and investor returns.

Writing in 2015, finance economists Robert S. Harris, Tim Jenkinson, and Steven N. Kaplan observed,[16]

“Buyout fund returns have exceeded those from public markets in almost all vintage years before 2006. Since 2006, buyout fund performance has been roughly equal to those of public markets.”

We can see this decline in performance in Figure 2, which shows cumulative performance of the median fund launched in each year from the year it was launched (its vintage year) to the fourth quarter of 2016. [17]

When comparing returns in private and public equities, it’s important to acknowledge that investing in private equity funds is riskier than investing in the stock market. The investments are illiquid — investors tie up their money for 10 years in a PE fund. A risk premium of 3 percent additional return above the stock market is necessary to compensate investors for this and other risks.[18]

The median fund launched in 2001 out-performed the market by an impressive cumulative 55 percent over the life of the fund. If the fund’s lifespan was 10 years, this is an average annual out-performance of 4.48%. This means that on average, the median PE firm beat the stock market by more than 4 percent each year. Half the funds launched that year did even better. The median PE fund launched in 2001 not only beat the stock market, but provided a return to investors that more than compensated them for the additional risk.

Cumulative out-performance of the median fund launched in 2005 was just 3 percent over 10 years, which implies a risk premium of just 0.3% each year on average. This is far below the 3 percent risk premium these investments should earn to compensate investors for their added riskiness. Since 2006, PE funds performed even more poorly. They just about matched the stock market — some vintages a little higher and some a little lower than the stock market. PE investors in the median fund received no risk premium at all and could have earned the same returns with far less risk by investing in a stock market index. Indeed, half the funds launched since 2006 have failed even to match the performance of a stock market index. Many others failed to provide a risk premium sufficient to account for the lack of liquidity and added risk of private equity investments.

For more than a decade, most retirees could have benefited more from passive investments by pension funds in stock market indexes than from the investments pension funds have made in private equity. Looking only at the absolute returns from investing in private equity misses the point that these riskier investments have failed to provide even higher returns than could have been earned with much less risk in the stock market. Yet limited partners continue to invest in private equity under the illusion — promoted by reliance on the IRR to measure performance — that these investments beat the market.[19]

As for the argument made by some limited partners, including pension trustees, that they only invest in top performing funds — outside of Lake Woebegone, this is clearly not possible for all investors. More importantly, the persistence that existed in the early years of private equity investing — in which a General Partner who had a top-performing fund had a high probability that the follow-on fund would also be top performing — disappeared more than 15 years ago.[20] The persistence of GP performance has declined substantially as the PE industry has matured and competition has increased. Today, past performance of a fund managed by a particular GP is no longer a good predictor of how that GP will perform in the future.

Your proposal will empower investors by increasing transparency around the true return of private equity investments so that investments professionals can make accurate comparisons. The legislation includes new annual reporting requirements, which require private equity funds to make public information about the amount of debt held by portfolio companies and information about the fees charged and actual return on investment. It would also require marketing materials for new funds to include information about historic performance, past bankruptcies of portfolio companies, workers hired and laid off by those companies, and past exit strategies from portfolio companies, which will allow investors like pension funds to determine whether those investments are consistent with their values. Finally, the legislation will end the increasingly prominent practice among the private investment firms of forcing limited partners to waive the fiduciary duties that require the investment firms to work in the best interest of their investors.

Conclusion

Companies owned by private funds touch millions of workers, tenants, students, borrowers, consumers, and families all across the country — and their reach is growing. In their quest to make money, many private equity firms have employed exploitive practices that not only hobble their portfolio companies, but also hurt the people who rely on them. The Stop Wall Street Looting Act will, for the first time, create sensible rules for the private equity industry that will allow productive investment to continue while halting the kinds of abusive practices that wipe out jobs and cripple strong companies.

Eileen Appelbaum, PhD

Co-Director and Senior Economist

[email protected]

[1] 2019 “Private markets come of age.” McKinsey & Company, https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Private%20Equity%20and%20Principal%20Investors/Our%20Insights/Private%20markets%20come%20of%20age/Private-markets-come-of-age-McKinsey-Global-Private-Markets-Review-2019-vF.ashx.

[2] Eileen Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt. 2014. Private Equity at Work: When Wall Street Manages Main Street, NY: Russell Sage Press.

[3] Edith Hotchkiss, David C. Smith and Per J. Str?mberg. 2012. “Private Equity and the Resolution of Financial Distress.” Working Paper. www.law.uchicago.edu/files/files/Stromberg.pdf

[4] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Board, Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. 2013. “Interagency Guidance on Leveraged Lending.” Washington, DC: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Board. https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/srletters/sr1303a1.pdf

[5] PitchBook. 2019. “2018 Annual US PE Breakdown.” Seattle, WA: PitchBook, p. 4. https://pitchbook.com/news/reports/2018-annual-us-pe-breakdown

[6] Ibid, p. 4.

[7] Kristen Haunss. 2019. “Update 1 – Leveraged loan credit risk warrants attention, regulators testify,” Loan Pricing Corporation, Reuters, May 15. https://www.reuters.com/article/levloan-risk/update-1-leveraged-loan-credit-risk-warrants-attention-regulators-testify-idUSL2N22R0XP; Jesse Hamilton. 2019. “Fed Challenged Over View that Leveraged Loans Won’t Cause Crisis,” Bloomberg, May 15. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-05-15/fed-s-quarles-challenged-over-view-of-leveraged-lending-s-threat; Dean Baker. 2018. “Corporate Debt Scares,” CEPR, October 11. https://cepr.net/blogs/beat-the-press/corporate-debt-scares

[8] John McNellis, 2019. “Retail’s Existential Threat is Private Equity,” The Registry, April 15. https://news.theregistrysf.com/mcnellis-retails-existential-threat-is-private-equity/

[9] Alana Semuels, 2019 “When Wall Street is Your Landlord,” The Atlantic, February 13. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2019/02/single-family-landlords-wall-street/582394/.

[10] Robert Kuttner and Hildy Zenger. 2017. “Saving the Free Press From Private Equity,” The American Prospect, December 27, https://prospect.org/article/saving-free-press-private-equity.

[11] Tracy Rucinski, 2018 “HCR ManorCare files for bankruptcy with $7.1 billion in debt,” Reutters, March 5, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-hcrmanorcare-bankruptcy-quality-care/hcr-manorcare-files-for-bankruptcy-with-7-1-billion-in-debt-idUSKBN1GH2BU.

[12] PitchBook. 2018. “2018 Annual Global PE Deal Multiples.” Seattle, WA: PitchBook, p. 3. https://files.pitchbook.com/website/files/pdf/PitchBook_2018_Annual_Global_PE_Deal_Multiples.pdf

[13] Eliza Ronalds-Hannon and David Scigliuzzo. 2019. “”Sycamore Pockets $1 Billion from Deal that Amazed Wall Street,” Bloomberg, April 11. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-04-11/sycamore-pockets-1-billion-from-deal-that-amazed-wall-street

[14] Rosemary Batt and Eileen Appelbaum. 2018. “Private Equity Pillage: Grocery Stores and Workers at Risk,” The American Prospect, October 26. https://prospect.org/article/private-equity-pillage-grocery-stores-and-workers-risk

[15] Eileen Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt. 2018. “Are Lower Private Equity Returns the New Normal?” in Michael Wright et al. (editors), The Routledge Companion to Management Buyouts, Routledge.

[16] Robert S. Harris, Tim Jenkinson, and Steven N. Kaplan.2015. “How Do Private Equity Investments Perform Compared to Public Equity?” Journal of Investment Management. Darden Business School Working Paper No. 2597259, June 15. Available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2597259.

[17] PitchBook. 2017. PE and VC Fund Performance. Data through Q4 2016.

[18] Risks specific to private equity include: leverage risk (potential for default and bankruptcy of portfolio company); business risk (some portfolio companies may face special risks as when Energy Future Holdings’ PE investors bet on price of natural gas rising and instead it collapsed); liquidity risk (investments by LPs are typically for a 10-year period and cannot be withdrawn if economic conditions change); commitment risk (uncertain timing of capital calls and distributions means that LPs may face difficulties if capital is called on short notice or distributions they are counting on are delayed); structural risk (potential for misalignment of GP and LP interests as when GP collects monitoring fees from a portfolio company that later reduces resale price of the company). See Appelbaum and Batt. 2018. “Are Lower Private Equity Returns the New Normal?” p. 254

[19] Rosemary Batt and Eileen Appelbaum. 2019. “The Agency Costs of Private Equity: Why do Limited Partners Funds Still Invest?” Academy of Management Perspectives. Forthcoming

[20] Robert S. Harris, Tim Jenkinson, Steven N. Kaplan and Ruediger Stucke. 2014. “Has Persistence Persisted in Private Equity? Evidence from Buyout and Venture Capital Funds.” SSRN Working Paper. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2304808; Reiner Braun, Tim Jenkinson, and Ingo Stoff. 2017. “How Persistent Is Private Equity Performance? Evidence from Deal-Level Data.” Journal of Financial Economics 123(2) (Feb.): 273-291.