July 20, 2015

Construction employers often talk about the labor shortages they face. The Associated General Contractors of America recently released a press release lamenting that “contractors are having a hard time finding enough qualified workers to meet growing demand in many parts of the country” as unemployment rates in the construction industry declined. The Atlantic wonders, “Where Have All the Construction Workers Gone?” To bolster claims of a shortage, the industry puts out reports based on non-scientific surveys of employers.

If there were a labor shortage in the construction industry, we would also expect there to be healthy wage growth. Employers would be competing over a smaller pool of workers, and higher wages would attract construction workers to the firms offering them (or entice workers in different industries or occupations to switch to construction). But if we look at year-over-year wage growth for production and non-supervisory workers in the construction industry, we see that wage growth is not especially high, similar to findings for other major industries.

Before the 2007–2009 recession, wage growth in construction peaked at 5.4 percent. In June 2015, it stood a full 3.0 percentage points lower, at 2.4 percent.

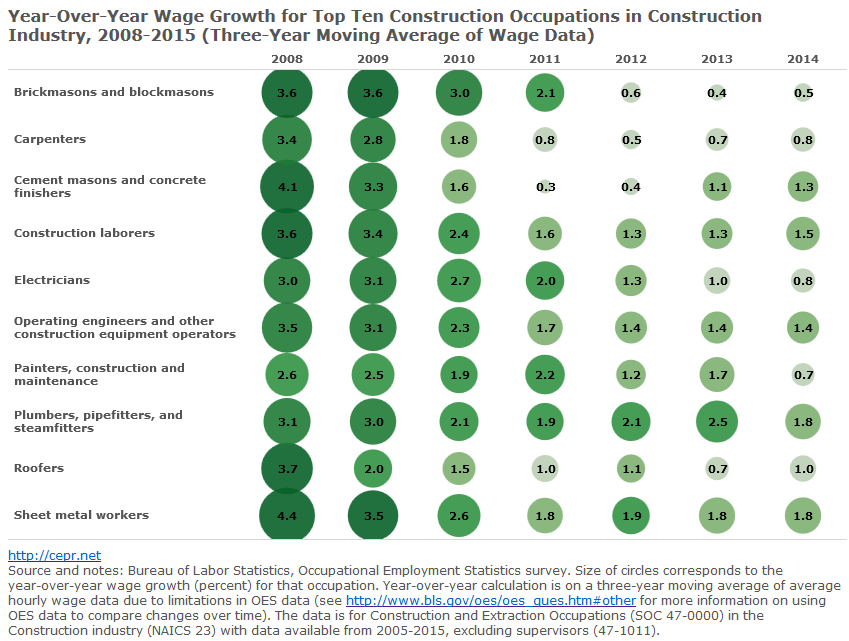

There is also yearly wage data for construction occupations. The year-over-year wage growth for the top ten construction occupations shows us that wage growth has generally declined since 2008, and growth in all ten occupations was under 2.0 percent in 2014. (See notes about the limitations of this data. Wage growth information for all occupations with data available is here.)

The two sets of wage growth data suggest that there is no labor shortage for the industry, at least nationally. So what does the construction industry’s low unemployment rate mean in context, and what explains employers’ inability to find workers?

Elise Gould at the Economic Policy Institute found in March that there were six unemployed construction workers for every construction opening. With the latest numbers, there are 140 thousand construction job openings and 674 thousand unemployed construction workers. This works out to close to five workers for every job opening—hardly a dearth of workers. But the pool of workers that the construction industry can draw from is not made up of only construction workers categorized as “unemployed” by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employers can attract employed and unemployed workers from other industries and convince workers to re-enter the labor market. And as I have recently pointed out, many workers left the labor force during the recession and the recovery. These missing workers also cause the unemployment rate to decline even if the conditions in the labor market have not improved. In the context of job openings and trends in the labor force, the industry’s low unemployment rate overstates the tightness of the labor market.

The other part of the problem might be explained by the “The Stupid Boss Theory.” Employers may not know that they need to raise wages to attract workers, or they may know, but not want to.

For the construction industry, it seems to be the latter. For example, home builders in Texas found it difficult to compete with wages in the oil and gas industry, so they decided to advocate for a construction guest worker program that will lower their labor costs by bringing in workers from other countries. (This is supported by two large industry groups.) Construction employers and industry groups also increasingly push for government training programs in and outside of our education system so that they do not need to pay for on-the-job training. If employers only look for workers that meet specific credentialing or training requirements, they may pass over workers that could learn skills on-the-job, which has historically been a way workers gain skills.

In sum, if employers are having a difficult time finding workers, they likely have unrealistic wage or skill expectations, probably because they are fixated on keeping their labor costs low.