May 06, 2020

This analysis was originally prepared for a discussion convened by the Institute for Work and the Economy, based in Chicago. Members of the Cook County Commission on Social Innovation, leaders of Chicago-area community based organizations, the head of the Chicago-Cook Workforce Partnership, local government representatives, and others were invited to and participated in the conversation.

CEPR previously released a report profiling workers in frontline industries. Workers in these industries have always been essential to our economy, and the pandemic has drawn attention to the vulnerabilities these workers face at work. The six broad industries we define as frontline include: Grocery, Convenience, and Drug Stores; Public Transit; Trucking, Warehouse, and Postal Service; Building Cleaning Services; Health Care; and, Child Care and Social Services (see our previous report for methodology). At the national level, we showed that workers in frontline industries are disproportionately women, live in low-income families, and are overrepresented by workers of color.

Illinois is one of the hardest hit states in the US by COVID-19, with more than 60,000 confirmed cases as of May 6. There are more than 1.3 million workers in frontline industries in Illinois. About 270,000 of these workers are in Chicago, while about 280,000 workers are in Chicago’s suburbs (Cook County, excluding Chicago).

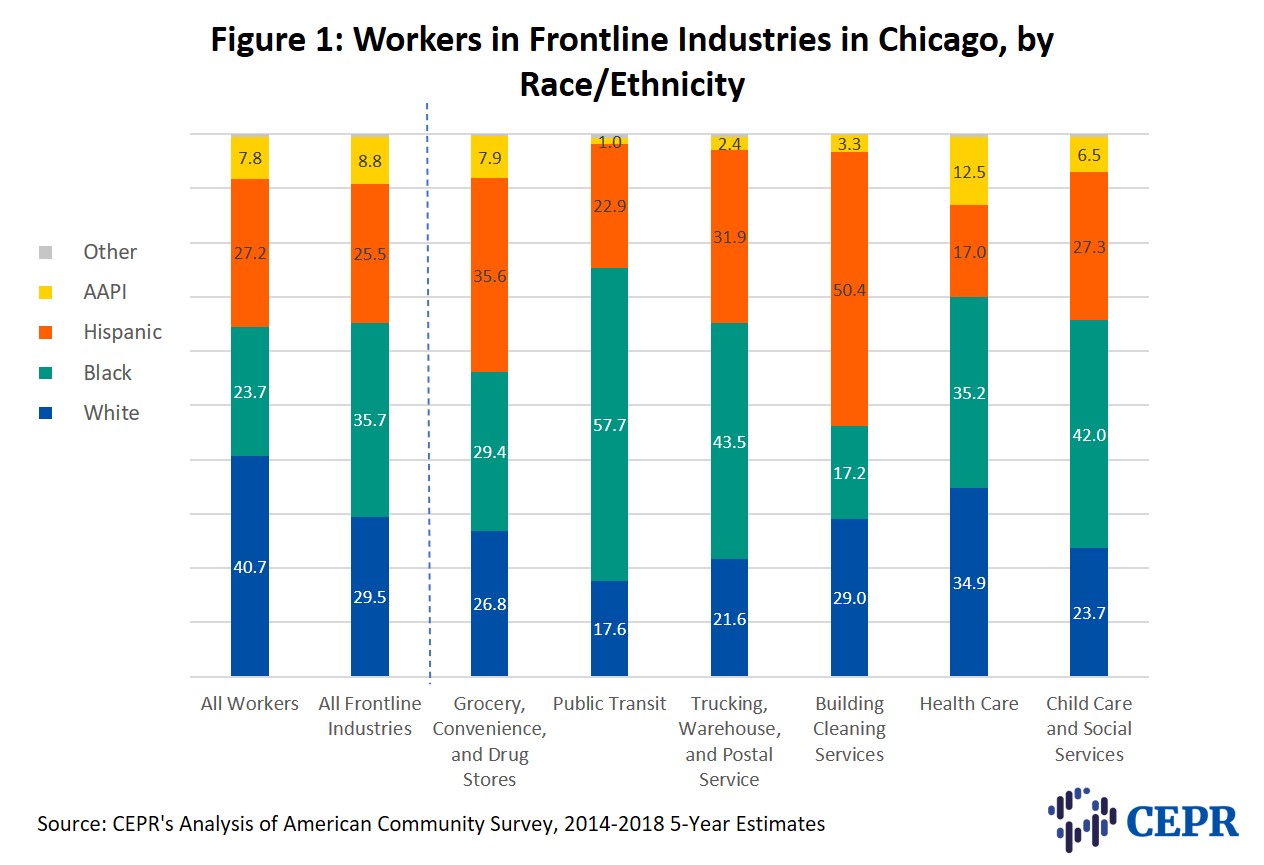

Women are far more likely to be in frontline industries than men in both Chicago and its suburbs (63.4 percent and 61.0 percent, respectively). Nonwhite workers are also overrepresented in Chicago’s frontline industries, as can be seen in Figure 1. Just under 60 percent of all workers in Chicago are nonwhite, but more than two-thirds (70.5 percent) of frontline workers in Chicago are nonwhite. Blacks are overrepresented in all frontline industries except for Building Cleaning Services, where more than half of the workforce is Hispanic (50.4 percent).

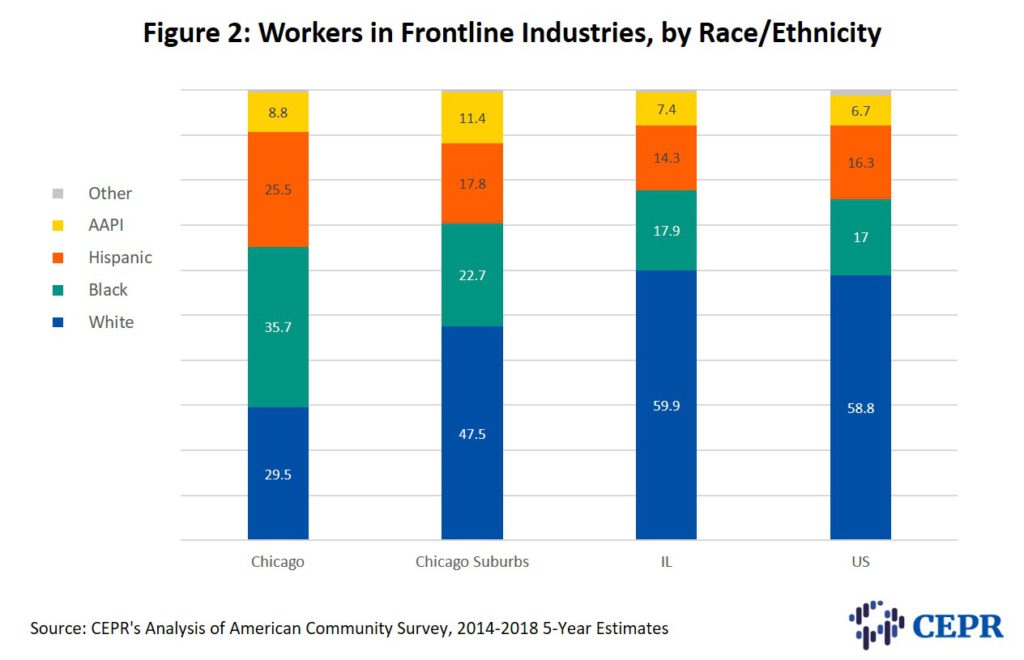

Figure 2 shows that the share of nonwhite frontline workers in the city of Chicago is far higher than those in Chicago’s suburbs, in Illinois, or in the US. In the city of Chicago, 35.7 percent of frontline workers are Black, and 25.5 percent of frontline workers are Hispanic. By comparison, Black and Hispanic workers make up 17 percent and 16.3 percent, respectively, of those workers in the frontline industries nationwide.

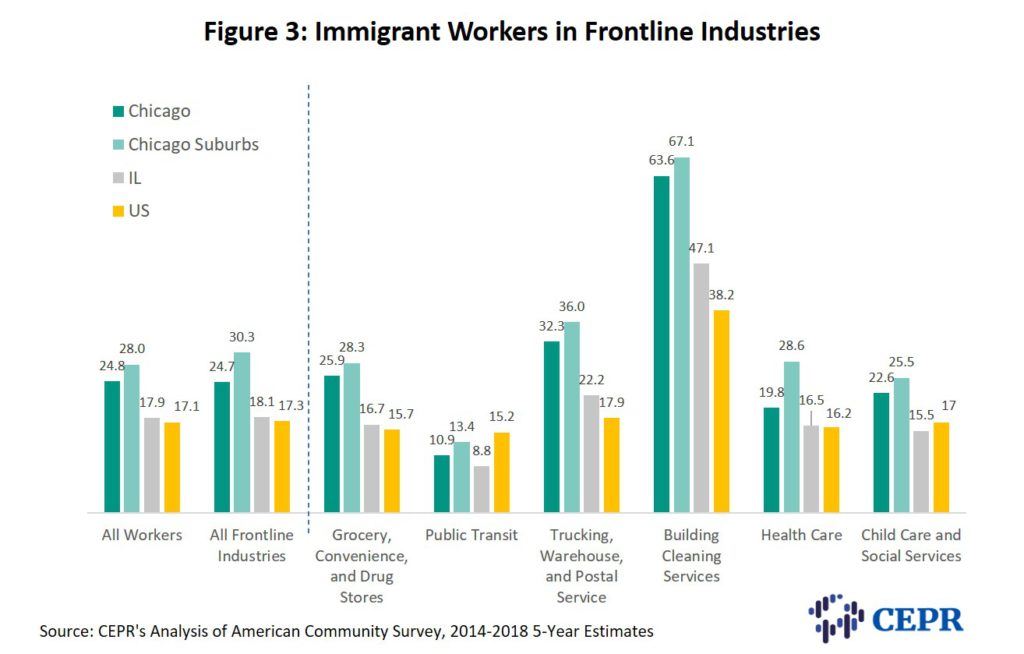

Immigrants make up a substantial portion of frontline workers in Chicago’s suburbs (30.3 percent), more than in the city of Chicago (24.7 percent), and in the US as a whole (17.3 percent). Figure 3 shows that some frontline industries employ more immigrants than others — for example, close to two-thirds of workers in Building Cleaning Services in both Chicago and its suburbs are immigrants (63.6 percent and 67.1 percent, respectively), and about a third of workers in Trucking, Warehouse, and Postal Service are immigrants (32.3 percent and 36.0 percent, respectively).

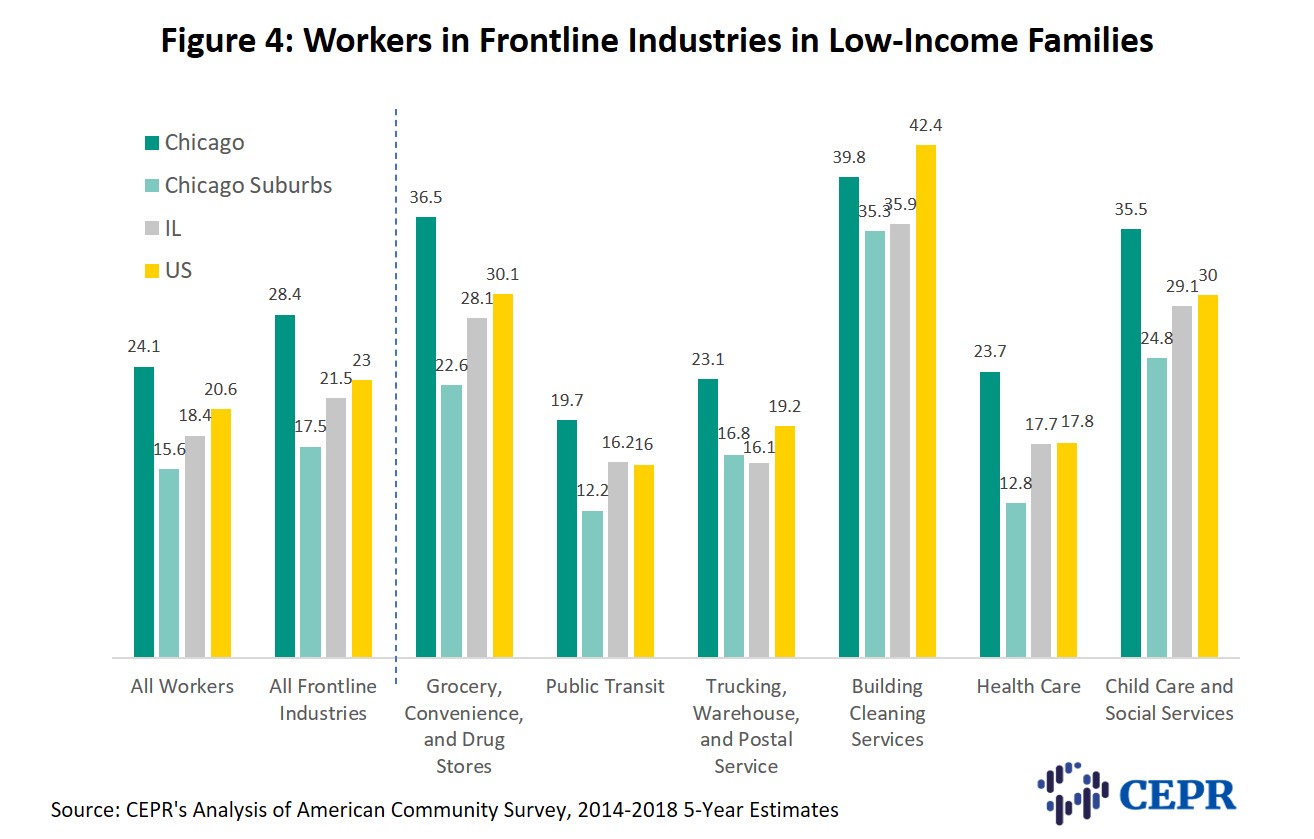

Workers in frontline industries in Chicago are disproportionately from low-income families. While 23 percent of all frontline workers in the US come from low-income families, 28.4 percent of frontline workers in Chicago do. This is also higher than the 24.1 percent of Chicago’s total workforce in low-income families. Figure 4 shows that low-income Chicago workers are overrepresented in Grocery, Convenience, and Drug Stores (36.5 percent), Building Cleaning Services (39.8 percent), and Child Care and Social Services (35.5 percent).

A higher percentage of frontline workers in Chicago’s suburbs have children or seniors at home than those in Chicago. In Chicago’s suburbs, 34.9 percent of frontline workers have one or more children at home, and 18.7 percent live with at least one senior (compared to 28.7 percent and 16.7 percent in Chicago, respectively).

While the COVID-19 legislation passed by Congress to date includes some important protections for frontline workers, too many of these workers remain under protected and under compensated. At the federal level, Senator Elizabeth Warren and Representative Ro Khanna have proposed an Essential Workers Bill of Rights that includes workplace health protections, hazard pay, paid sick days, and other protections. The New York City Council is currently considering a package of similar policies for essential workers.

In Chicago, Mayor Lori Lightfoot proposed the COVID-19 Anti-Retaliation Ordinance, which would ensure, “that employees will be able to remain at home if they have COVID-19 symptoms or are subject to a quarantine isolation order without fear of being fired.” This builds on Chicago’s Paid Sick Leave Ordinance. Cook County also has the Earned Sick Leave Ordinance that provides job protected compensated leave for specified permissible uses. This covers virtually all suburban Cook County workers except in home rule communities that have opted out. States and other large cities, including Illinois and Chicago, should expand their efforts to ensure that essential workers, those specifically on the frontlines of the pandemic, receive the compensation and protection they deserve.

A regional COVID-19 Recovery Task Force has been formed in Chicago to, in part, “conduct a ‘change study’ to gauge the full extent of economic hardship and to provide a baseline for the city as well as the business community.” From the perspective of Chicago, this study will “help prioritize growth in key industry sectors that have either seen significant losses, or which hold potential for workforce growth in a post COVID-19 economy”