February 08, 2016

In 1996, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that unemployment would rise from 5.8 to 6.0 percent the next year and stay at that rate into the 2000s. The consensus among most economists and policy experts was that 6.0 percent unemployment was the lowest the unemployment rate could fall to before it caused inflation (this rate is known as the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment, or NAIRU), even though inflation was already very low.

In their minds, this meant the Federal Reserve (Fed), which has an obligation to pursue low unemployment, should keep interest rates as high as necessary to prevent the unemployment rate from falling much below 6.0 percent. While it might be possible to lower interest rates to reduce unemployment, as some economists and activists advocated for, the mainstream view was that this would not be worth the cost of higher inflation.

Alan Greenspan, then chair of the Fed, and Janet Yellen, the chair today, seemed to go along with that consensus. Yellen even called low interest rates to promote growth and employment “a very confused set of arguments.”

But over the next four years, Greenspan broke with orthodoxy and used his influence to keep rates relatively low, unlike during the expansion in the 1980s. In 1997, when unemployment had dipped below 6.0 percent without an uptick in inflation, Paul Krugman doubled down on his belief that this would lead to accelerating inflation. He, like many other commentators, was wrong.

The table below shows that the unemployment rate declined to 4.0 percent by 2000, and, by four measures of inflation, did not seem to result in much, if any, increase in inflation during that time period. Insofar as there was an increase in inflation in 1999 to 2000, almost all of it was due to a jump in world oil prices which cannot be blamed on Fed policy.

|

Year |

Unemployment, Actual |

Unemployment, 1996 CBO projection |

C.P.I. |

Core C.P.I. |

G.D.P. Price Index |

P.C.E. Less Food/Energy |

|

1995 |

5.6% |

5.8% |

2.5% |

3.0% |

2.1% |

2.3% |

|

1996 |

5.4% |

6.0% |

3.3% |

2.6% |

1.9% |

1.9% |

|

1997 |

4.9% |

6.0% |

1.7% |

2.2% |

1.8% |

1.9% |

|

1998 |

4.5% |

6.0% |

1.6% |

2.4% |

1.1% |

1.5% |

|

1999 |

4.2% |

6.0% |

2.7% |

1.9% |

1.5% |

1.5% |

|

2000 |

4.0% |

6.0% |

3.4% |

2.6% |

2.2% |

1.7% |

|

2001 |

4.7% |

n.a. |

1.6% |

2.7% |

2.3% |

1.8% |

Source: Adapted from The New York Times.

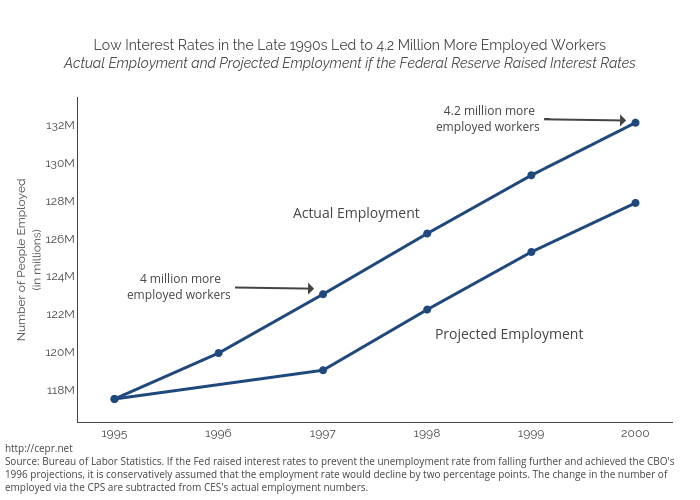

And because Greenspan kept interest rates low and allowed unemployment to fall further, it led (by a conservative estimate) to jobs for 4.2 million more people than if interest rates were raised to maintain unemployment at 6.0 percent. Whatever his reasons for doing so, Greenspan’s decision to ignore the economic consensus of the day led to large improvements in the lives of many people. The Fed should keep this in mind when debating interest rate policy today.