December 10, 2015

In late 2007, the Federal Reserve (“Fed”) began pushing down interest rates in hopes of boosting the economy and providing job opportunities for American workers. The downside to lower interest rates is the risk of higher inflation; at the time, the Fed correctly believed that inflation wasn’t a problem, given that all measures of inflation were near their stated targets and falling.

The Fed made a hard push to boost employment by lowering the Federal Funds Rate — the rate at which banks can lend to each other overnight — from 5.25 percent in early 2007 all the way to 0.16 percent in December 2008. The Fed has kept the Federal Funds Rate near zero for the last seven years.

When the Fed meets on December 15–16, it will consider raising rates despite the fact that the labor market by at least one key measure is only about halfway recovered from the 2007–2009 recession. Moreover, inflation is hardly a problem in today’s economy. By all measures inflation is low, and projections of future inflation indicate that the Federal Reserve is likely to remain below its target rate of 2.0 percent.

So when the Fed votes on whether or not to raise interest rates next week, it will be choosing between reducing the risk of a potential future problem (inflation) and a very real present one (low employment). There is substantial disagreement amongst members of the Fed about which problem is more important.

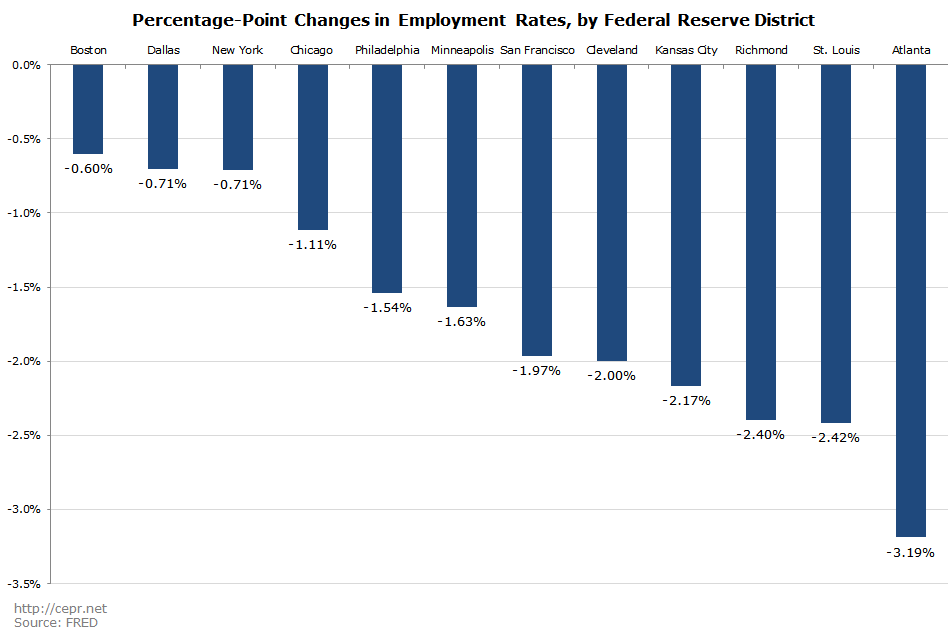

However, if the Fed were a more democratic institution — one in which Federal Reserve District Presidents were expected to respond to the needs of the people within their districts — it’s likely that they would view the trade-offs differently. This is because every single Federal Reserve district has a lower employment rate today than it did in 2007. The figure below shows the difference between the average employment rate for August to October 2015 compared to the average rate from the same three months from 2007. The figure was constructed using data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve on each region’s unemployment rate, civilian labor force, and resident population.

While there are striking differences in terms of the amount of employment each district has lost, the basic story remains the same: the employment rate is still below its pre-recession level. Any regional president who votes for higher rates will be voting to slow the recovery in his or her own district.