March 20, 2023

New data from the Census and Department of Housing and Urban Development on housing permits and starts show an uptick in activity. But caution is warranted, as recent news about the banking industry and the Federal Reserve’s upcoming meeting could potentially throw a wrench in any rebound in housing construction.

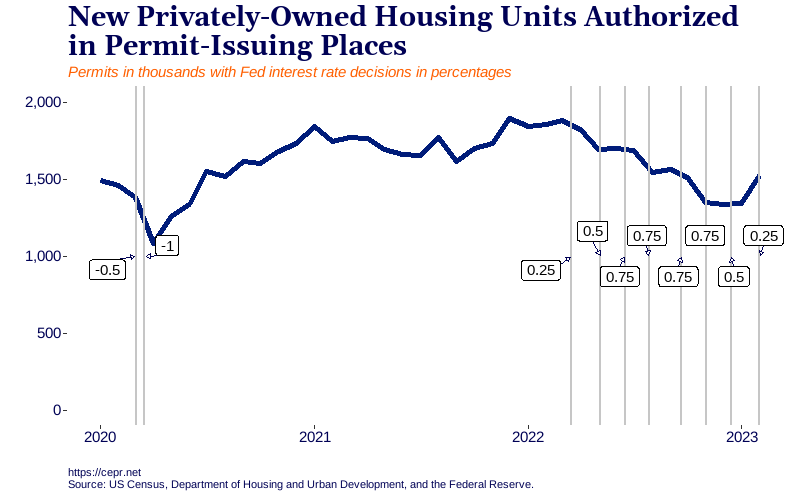

Let’s start with the good news. According to the latest data, the number of new privately-owned housing permits authorized and housing projects started increased in February 2022. For permits, 1,524,000 were issued in February, 13.8 percent above the revised January rate of 1,339,000. And 1,450,000 construction projects were started in February, 9.8 percent (±15.5 percent) above the revised January estimate of 1,321,000. For permits issued, it’s the first increase since the Federal Reserve started raising interest rates a year ago on March 17, 2022.

Now, the cautionary news. First, the data released are preliminary estimates and can be revised upward or downward in the coming months. Second, while the numbers appear impressive, HUD notes both permits and starts are 17.9 percent and 18.4 percent below the February 2022 rates, respectively. Finally, the Fed meets on March 22 and is expected to increase interest rates by another 0.25 percentage points. The Fed has used raising interest rates as a tool for fighting inflation. However, the Fed is also tasked with maintaining the banking system’s stability. There’s a chance the Fed’s response to inflation might be muted in the wake of the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, in which the rapid increase in interest rates played a role. But if the Fed raises rates anyway, this could hurt housing construction even more.

To understand why interest rates have a depressing effect on residential housing construction, we must look at housing from multiple angles. First, developers rely on financing to build homes. This financing can come from debt, such as money from lenders, or equity, such as money from investors. In the case of debt, this is typically a loan from a bank. These loans often do not cover the project’s entire cost, requiring developers to partially cover expenses to minimize risk to the bank. An investor can cover the gap completely or partially, sharing expenses with the developer. Either way, the developer shoulders quite a bit of risk. When you add increasing interest rates, the costs that fall on the developer rise, making a project riskier.

On the consumer side, lower interest rates benefit home buyers and sellers. A lower interest rate reduces monthly mortgage payments, and increased demand raises the prices of homes on the market. As interest rates increase, demand decreases as new mortgages become prohibitively pricey for home buyers. While this decrease in demand lowers home prices, the cost of entering the market becomes too high for some.

All of this is to say that we can expect housing permits to fall with higher interest rates as risks increase for developers and higher mortgage rates scare buyers away. The February data buck that trend. But housing is an issue that differs by region, state, and even locality. A decline in housing permits in Huntington Beach, CA, is a very different issue from an increase in permits in the drought-stricken Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise metro area, where a growing population is placing demand on water management efforts. A macro view only tells us so much.

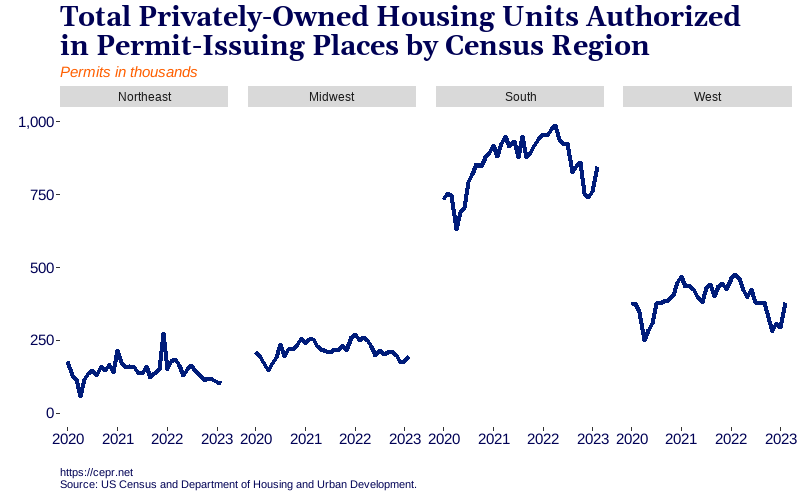

Looking at the data by Census region, permits issued in the Northeast and Midwest are far below the South and West, with the Northeast experiencing a continued decline in February. This phenomenon aligns with Census data that found eight of the 15 fastest-growing large cities or towns by percentage change were in the West and South. Many of these cities are in Texas, Arizona, and Florida, which places more and more of the US population in areas prone to climate-related disasters. Many parts of Arizona and Texas remain in extreme long-term drought conditions, and Florida (as well as the rest of the Gulf Coast) continues to tackle the double threat of stronger hurricanes and sea-level rise.

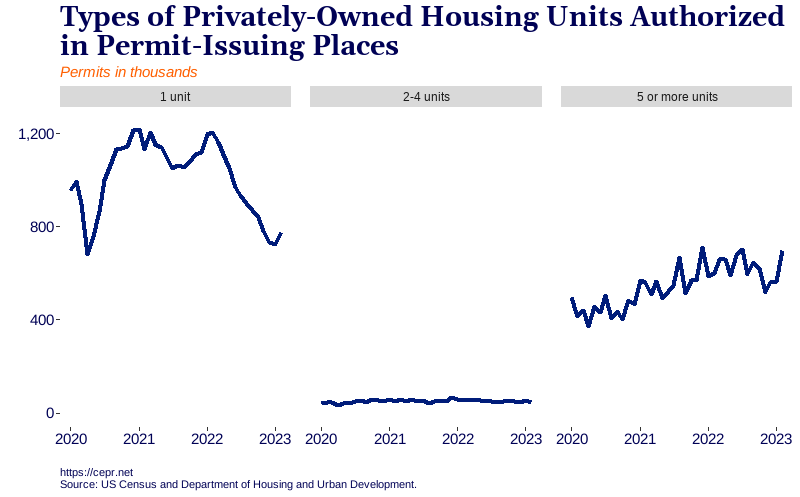

Breaking the data down by housing type shows that while permits for middle- to high-density housing, represented as five units or more, are increasing, more permits for single-family units are being issued. In major cities across the US, single-family zoning, which has its origins in the practice of redlining, has prevented access to affordable housing. Housing advocates have pushed for zoning reform, particularly encouraging more middle-density housing in the form of accessory dwelling units, duplexes, and medium-sized apartment and condo buildings. According to a report by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation, building more of this missing middle housing would increase the availability of more affordable “starter homes,” allowing new buyers to enter the housing market. Other research has found that in the Bay Area, a region of California unaffordable for most middle- to low-income families, single-family homes are approximately 2.7 times more expensive than 2-4 unit buildings. But as the figure below shows, permits issued for projects containing 2-4 units across the US continue to decline.

As noted above, developers must consider the risk of losing money on a project. This risk-averseness helps explain why developers choose projects in regions where there is a prospect of higher returns and projects with little to no regulatory obstacles. This risk-averseness is also why single-family homes are more popular with developers. If interest rates continue to climb, we may see this pattern continue, jeopardizing affordable housing goals.

While it is essential to watch for rate increases coming out of the Fed meeting, another potential issue is the prospect of banks issuing fewer loans after the Silicon Valley Bank collapse. That move would affect developers and home buyers, but it’s too early for the data to pick up any effects from what’s happening right now. The most current data we have are the responses of permits and starts to increasing interest rates. Over the past year, politicians and activists have warned how continuing to raise interest rates will hurt workers. We may have to add affordable housing to that list.