October 28, 2014

A post at Wonkblog earlier this month noted that a recent analysis by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) of regional well-being across its member countries found that the U.S. South was “the worst place to live in the United States.” The OECD –as diplomatic as it is– did not say this in so many words, but Wonkblog reporter Roberto Ferdman pulled together the OECD’s state-level data for the United States and it would be hard to arrive at any other conclusion.

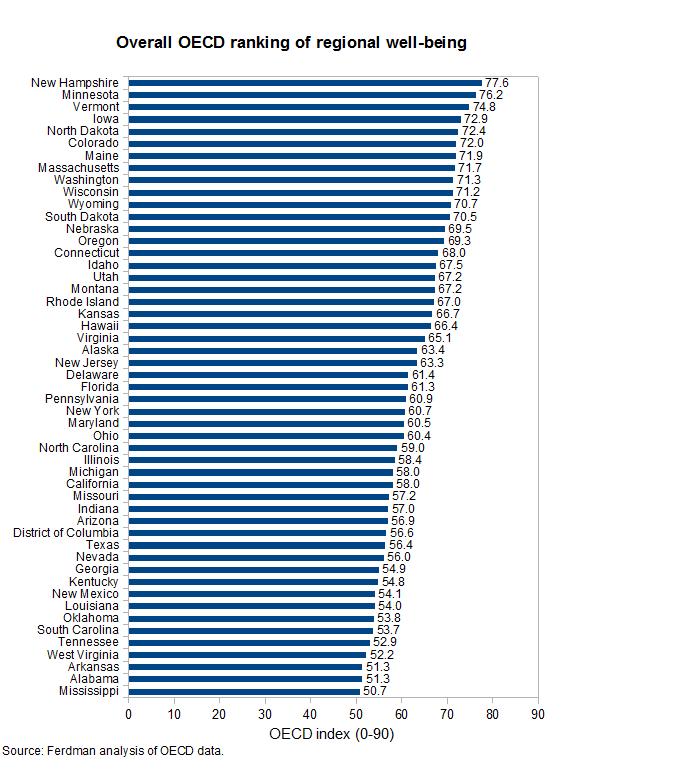

For each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, the chart below gives the OECD’s overall well-being score, which consolidates the organization’s nine separate measures, reflecting health, jobs, safety, environment, access to services, civic engagement, housing, education, and income. Possible scores ranges from a low of zero to a perfect score of 90. In the United States, the lowest recorded score was 50.7 for Mississippi and the highest was New Hampshire at 77.6.

As Wonkblog highlighted, the chart shows a heavy concentration of southern states at the bottom –and the complete absence of southern states at the top. Ferdman writes: “The South, which performed the worst of any region in the country, is home to eight of the poorest performing states. Only Virginia was in the top 25. And just barely — it placed 22nd.” A similar pattern holds in the nine subcomponents of the OECD’s overall index.

A few days later, Wonkblog ran a defense of the South –and of the OECD– written by Carol Guthrie, an OECD official in Washington, who also happens to be a die-hard daughter of the South. Guthrie emphasized that the OECD’s measures are “objective” and can’t capture the many subjective reasons that southerners love the South. The OECD, she said, was simply listing a set of “criteria that underpin economic as well as physical well-being, including things that make our regions more or less competitive and able to provide vibrant quality of life.” Quoting the OECD’s Secretary General Angel Gurria, Guthrie wrote that these indicators can be used to “offer a new way to gauge what policies work and can empower a community to act to achieve higher well-being for its citizens.”

So, what happens if we take up Guthrie and Gurria’s suggestion to use the well-being measures “to gauge what policies work”? Well, the most striking feature of the Wonkblog chart and of the OECD’s regional data more generally is how at odds the performance of the South is with long-standing policy preferences at the OECD. The South is almost certainly the region of the world that has most embraced in principle and has most embodied in practice the policies promoted by the OECD. Relative to the rest of the rich world, the states of the South have among the stingiest unemployment benefit systems, the least unionized workforces, the lowest minimum wages, the smallest public sectors, the weakest employment protection laws, and the lowest taxes. By standard OECD analysis, the South ought to be a workers’ paradise. But, based on the indicators that Guthrie decribes as “cold, hard facts” for “policymakers and citizens looking to bring about change,” the South performs disastrously.

To be fair, in recent years, the OECD has softened its stance on some of these issues, such as the minimum wage. And the OECD has long been a champion of increased investment in education, where the South also does poorly relative to the rest of the United States.

But, is it too much to hope that the OECD would use these new regional data to rethink their policy recommendations? At least when it comes to the United States?