Haiti: Relief and Reconstruction Watch is a blog that tracks multinational aid efforts in Haiti with an eye towards ensuring they are oriented towards the needs of the Haitian people, and that aid is not used to undermine Haitians' right to self-determination.

• HaitiHaitiJovenel MoïseJovenel MoïseUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

• HaitiHaitiLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

• HaitiHaitiLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

• HaitiHaitiPras MichelRandall ToussaintRudy MoiseWyclef Jean

• HaitiHaitiLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

In late March, Wesley Clark, a retired four-star US military general and one-time Democratic presidential candidate, reached out to Haiti’s de facto prime minister, Ariel Henry. Clark was writing as chairman of the Studebaker Defense Group, a multinational security contractor that includes many former Pentagon and CIA officials among its ranks, and invited Henry to join him for a business meeting at the Haitian Embassy in DC on March 31, 2023.

“I invite you to join me at the event and hope to have discussions regarding potential Security Sector Reform initiatives in Haiti,” the retired general wrote in the letter, obtained by HRRW. “We would also like to host you for a private dinner in the evening of the 31st should you be available.”

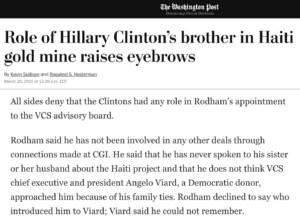

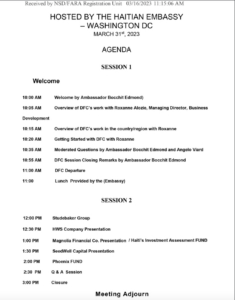

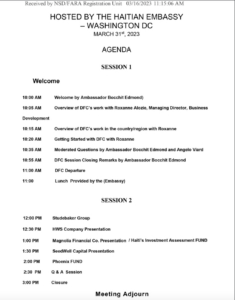

Henry did not travel to DC, but the embassy did host an event on March 31 where Studebaker officials and other private sector actors were present, according to a draft agenda contained in a Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA) disclosure. The registered lobbyist, Angelo Viard, filed the paperwork in mid-March, stating that he had been authorized to work on behalf of Prime Minister Henry. The documents indicate that Viard, a Haitian-American businessman and the former CEO of VCS mining, is performing the work on a volunteer basis and that he had also helped organize a meeting between Henry and private sector actors last year in Miami.

First on the agenda for the March 31 meeting was a presentation and Q and A session with Roxanne Alozie, director of business development at the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), a government entity that “partners with the private sector to finance solutions to the most critical challenges facing the developing world today,” according to its website. Later in the day, there were presentations from the Studebaker Group as well as HWS, Magnolia Financial Co., Seedwell Capital, and the Phoenix Fund.

“DFC staff regularly conducts presentations to interested business communities, including diaspora and affinity groups, to explain how DFC works,” Pooja Jhunjhunwala, a spokesperson for DFC, explained in a written statement. “The March 31 event was hosted and managed by the Embassy of Haiti.” Bocchit Edmond, Haiti’s ambassador, did not respond to a request for comment.

Though neither Clark nor Henry ended up personally attending the embassy event, five days later, Clark and other Studebaker officials traveled to Port-au-Prince where they met with the de facto prime minister in the airport’s diplomatic salon. The meeting was confirmed by both Studebaker and a spokesperson for the prime minister. “The purpose of the discussion was to discuss potential Haiti security reform initiatives,” a Studebaker official explained. “We currently have no formal relationship with the government of Haiti or with Mr. Angelo Viard,” they added. The prime minister’s spokesperson did not provide any further details of the meeting or what was discussed.

The meeting occurred roughly seven months after Henry formally asked the international community to lead a military intervention in Haiti. Those calls, however, have thus far failed to translate into any concrete action, despite public support from the US and UN. Earlier this month, media outlets reported on leaked US intelligence documents that claimed the Russian state-affiliated Wagner Group “planned to discreetly travel to Haiti to assess the potential for contracts with the Haitian government to fight against local gangs.” A Haitian government official told the Miami Herald that there had been no meetings with the Wagner Group, and the leaked documents contain no actual evidence of their presence in Haiti.

Interestingly, in 2021, Studebaker Defense Group formed a partnership with a notorious South African mercenary group, Executive Outcomes. The group, founded by Eeben Barlow, a former Colonel in the Apartheid-era South African Defense Forces, was active across the African continent, as well as in South America and Asia, until they closed in the late ‘90s. Barlow reconstituted Executive Outcomes in 2020. He now sits on the board of Studebaker Defense Group, where he is listed as “Strategic Advisor Africa.” According to Intelligence Online, the partnership was intended to create a rival to the Wagner Group, which is also present in Africa.

This is not Clark’s first foray into Haiti as part of the private sector. Less than a month after the 2010 earthquake, Clark traveled to Haiti and met with then-president René Préval in order to give “a sales presentation on a hurricane/earthquake resistant foam core house designed for low income residents,” according to a diplomatic cable released by Wikileaks. Clark sat on the board of the company, InnoVida Holdings, which eventually received a $10 million loan from the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation, the predecessor of the DFC. The company, however, never built any houses. In 2012, InnoVida’s CEO, Claudio Osorio, was arrested on fraud charges. He eventually plead guilty and was sentenced to 12 years in prison for bilking investors of some $40 million and making false representations in the OPIC loan application.

Years later, Clark told the press that, despite being listed as a board member of InnoVida, he had only been recruited to join the board before eventually declining. “I’ve learned that when it smells, get away,” Clark said at the time.

In late March, Wesley Clark, a retired four-star US military general and one-time Democratic presidential candidate, reached out to Haiti’s de facto prime minister, Ariel Henry. Clark was writing as chairman of the Studebaker Defense Group, a multinational security contractor that includes many former Pentagon and CIA officials among its ranks, and invited Henry to join him for a business meeting at the Haitian Embassy in DC on March 31, 2023.

“I invite you to join me at the event and hope to have discussions regarding potential Security Sector Reform initiatives in Haiti,” the retired general wrote in the letter, obtained by HRRW. “We would also like to host you for a private dinner in the evening of the 31st should you be available.”

Henry did not travel to DC, but the embassy did host an event on March 31 where Studebaker officials and other private sector actors were present, according to a draft agenda contained in a Foreign Agent Registration Act (FARA) disclosure. The registered lobbyist, Angelo Viard, filed the paperwork in mid-March, stating that he had been authorized to work on behalf of Prime Minister Henry. The documents indicate that Viard, a Haitian-American businessman and the former CEO of VCS mining, is performing the work on a volunteer basis and that he had also helped organize a meeting between Henry and private sector actors last year in Miami.

First on the agenda for the March 31 meeting was a presentation and Q and A session with Roxanne Alozie, director of business development at the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), a government entity that “partners with the private sector to finance solutions to the most critical challenges facing the developing world today,” according to its website. Later in the day, there were presentations from the Studebaker Group as well as HWS, Magnolia Financial Co., Seedwell Capital, and the Phoenix Fund.

“DFC staff regularly conducts presentations to interested business communities, including diaspora and affinity groups, to explain how DFC works,” Pooja Jhunjhunwala, a spokesperson for DFC, explained in a written statement. “The March 31 event was hosted and managed by the Embassy of Haiti.” Bocchit Edmond, Haiti’s ambassador, did not respond to a request for comment.

Though neither Clark nor Henry ended up personally attending the embassy event, five days later, Clark and other Studebaker officials traveled to Port-au-Prince where they met with the de facto prime minister in the airport’s diplomatic salon. The meeting was confirmed by both Studebaker and a spokesperson for the prime minister. “The purpose of the discussion was to discuss potential Haiti security reform initiatives,” a Studebaker official explained. “We currently have no formal relationship with the government of Haiti or with Mr. Angelo Viard,” they added. The prime minister’s spokesperson did not provide any further details of the meeting or what was discussed.

The meeting occurred roughly seven months after Henry formally asked the international community to lead a military intervention in Haiti. Those calls, however, have thus far failed to translate into any concrete action, despite public support from the US and UN. Earlier this month, media outlets reported on leaked US intelligence documents that claimed the Russian state-affiliated Wagner Group “planned to discreetly travel to Haiti to assess the potential for contracts with the Haitian government to fight against local gangs.” A Haitian government official told the Miami Herald that there had been no meetings with the Wagner Group, and the leaked documents contain no actual evidence of their presence in Haiti.

Interestingly, in 2021, Studebaker Defense Group formed a partnership with a notorious South African mercenary group, Executive Outcomes. The group, founded by Eeben Barlow, a former Colonel in the Apartheid-era South African Defense Forces, was active across the African continent, as well as in South America and Asia, until they closed in the late ‘90s. Barlow reconstituted Executive Outcomes in 2020. He now sits on the board of Studebaker Defense Group, where he is listed as “Strategic Advisor Africa.” According to Intelligence Online, the partnership was intended to create a rival to the Wagner Group, which is also present in Africa.

This is not Clark’s first foray into Haiti as part of the private sector. Less than a month after the 2010 earthquake, Clark traveled to Haiti and met with then-president René Préval in order to give “a sales presentation on a hurricane/earthquake resistant foam core house designed for low income residents,” according to a diplomatic cable released by Wikileaks. Clark sat on the board of the company, InnoVida Holdings, which eventually received a $10 million loan from the US Overseas Private Investment Corporation, the predecessor of the DFC. The company, however, never built any houses. In 2012, InnoVida’s CEO, Claudio Osorio, was arrested on fraud charges. He eventually plead guilty and was sentenced to 12 years in prison for bilking investors of some $40 million and making false representations in the OPIC loan application.

Years later, Clark told the press that, despite being listed as a board member of InnoVida, he had only been recruited to join the board before eventually declining. “I’ve learned that when it smells, get away,” Clark said at the time.

• HaitiHaitiLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

Six weeks after Haiti’s de facto government requested a foreign military intervention amid unprecedented levels of insecurity and the United States began work on a UN Security Council resolution authorizing a “rapid action force,” regional leaders are speaking out in opposition to the plan. Over the past few weeks, multiple countries, including Canada, which the US had hoped would lead such a mission, have said that political changes are a necessary first step. At the same time, as the weeks pass, the mandate and scope of a possible foreign military intervention appears to be changing.

“The security situation cannot be divorced from the political situation,” Ralph Gonsalves, prime minister of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, told the press following a meeting between US, Canadian, and CARICOM leaders in mid-November. He said that first, Haitian actors would need to come together and define the path forward.

“Unless you address that political question of a national dialogue bringing about this government of national unity, an inclusive government, you’re not going to be able to solve properly the security question because any security force which goes in there would be looked at with suspicion as though they’re propping up the current Haitian government,” the Western Hemisphere’s longest-serving political leader explained.

Gonsalves said that some countries instead favor a rapid response, not contingent on any political accord, and, he explained, those countries have been heavily lobbying CARICOM nations to get their support for such a mission. “Well, one thing I’ll tell you, St. Vincent and the Grenadines will not be sending any police in that situation because I don’t want anybody to interpret us as going to send the police there to help to prop up the government,” he said.

Though he did not mention any other countries by name, the reference is likely to the United States, which has remained a steadfast ally to Haiti’s de facto prime minister, Ariel Henry. While the US has been the most vocal proponent of a foreign-led security mission in Haiti, it has thus far refused to contribute its own personnel and has been persistently reaching out to other nations in the hope of finding a third party to take the lead. Those efforts have focused primarily on Canada, and included a visit to Ottawa by Secretary of State Antony Blinken last month.

Canada, while not explicitly rejecting the idea that it could lead such an intervention, has said it is considering its options. But, last week, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau publicly backed Gonsalves’s analysis.

“It is not enough for Haiti’s government to ask for it,” Trudeau said. “There needs to be a consensus across political parties in Haiti before we can move forward on more significant steps.” The Canadian leader once again said his country was open to participating in a military intervention, but that “we must have a Haitian consensus” first.

The US has approached a number of other countries about participating in such a mission, including Brazil, which led the last United Nations military force in Haiti, MINUSTAH, from 2004 to 2017. Diplomatic cables published by WikiLeaks reveal that, at the time, the US sought to find a third-party country to lead the UN mission as a way to save money and outsource its control over Haiti. “Without a UN-sanctioned peacekeeping and stabilization force, we would be getting far less help from our hemispheric and European partners in managing Haiti,” the then ambassador wrote in 2008.

But it appears Brazil has little appetite in returning to Haiti now. “Any Brazilian participation would be difficult, overall in a multinational force,” Celso Amorim, Brazil’s former foreign minister and a top advisor to president elect Lula da Silva, told Reuters. “We made an enormous effort that brought us a lot of problems, even internally,” he said.

Of course, obtaining UN authorization at all remains a question mark. China and Russia, who both hold veto power at the Security Council, have expressed skepticism. Last month, the Miami Herald reported that the US was “planning contingencies for a multilateral force that would enter Haiti without formal U.N. authorization,” though it is unclear if that could mean the deployment of US military assets.

What is clear, however, is that the US appears committed to at least some sort of foreign security intervention in Haiti. In closed-door meetings in recent weeks, US officials have repeatedly indicated their optimism that something will be done.

“No Strategic Clarity”

“We’re very supportive of something to be done for Haitian people,” Gonsalves, the St. Vincent & the Grenadines prime minister said. “But you have to learn properly the humanitarian, the security and the political. You can’t just link humanitarian and security and forget the political and there is a lot of tactical confusion because there is no strategic clarity.”

The military intervention was initially framed as a “rapid action force” that would help unblock the country’s main fuel terminal in Port-au-Prince and help to resolve the immediate humanitarian situation. “This resolution will propose a limited, carefully scoped” mission, Linda Thomas Greenfield, the US Ambassador to the UN, told the security council in mid-October.

However, more than a month has passed and the fuel terminal has been operational for two weeks. Meanwhile, the scope of a possible mission appears to have expanded.

“There continue to be longer-term challenges that an enabling force authorized by the UN Security Council would be able to help address,” State Department spokesperson Ned Price said, in response to a question about if the resumption of fuel deliveries had lessened the need for an intervention. Thomas Shannon, a former high ranking US diplomat, suggested that what Haiti really needs is a long-term “state-building” mission akin to U.S. efforts in Afghanistan.

After initially saying the plan would be ready by early November, last week, the Miami Herald reported that the US sees little hope for progressing its UN resolution over the holidays — pushing a potential timeline out until early in 2023. “A second U.S. official said that the plan is not dead, but that the formation of such an ambitious military mission would take time,” the Herald reported.

Nobody, it seems, has any idea what this military endeavor would actually look like. A spokesperson from the French embassy told Politico: “To date, the contours of this possible intervention force have yet to be specified.”

“The problem is that nobody really believes that you can restore order and leave quickly,” Richard Gowan of the International Crisis Group said earlier this month.

In 2004, following the February coup d’etat against Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the de facto government requested urgent foreign military assistance. The same day as Aristide was flown into exile, the Security Council authorized the deployment of a three-month multinational force led by the US and Canada. That, however, was always just a stop gap measure while longer-term preparations for the arrival of the UN Blue Helmets took place. That mission stayed for 13 years.

Though pitched to the world as a fine-tuned intervention only to help address a dire humanitarian situation, the US’ failure to find immediate support has revealed what has likely been the case all along: any military intervention is likely to morph into yet another long-term, foreign-led attempt at nation building in Haiti.

Six weeks after Haiti’s de facto government requested a foreign military intervention amid unprecedented levels of insecurity and the United States began work on a UN Security Council resolution authorizing a “rapid action force,” regional leaders are speaking out in opposition to the plan. Over the past few weeks, multiple countries, including Canada, which the US had hoped would lead such a mission, have said that political changes are a necessary first step. At the same time, as the weeks pass, the mandate and scope of a possible foreign military intervention appears to be changing.

“The security situation cannot be divorced from the political situation,” Ralph Gonsalves, prime minister of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, told the press following a meeting between US, Canadian, and CARICOM leaders in mid-November. He said that first, Haitian actors would need to come together and define the path forward.

“Unless you address that political question of a national dialogue bringing about this government of national unity, an inclusive government, you’re not going to be able to solve properly the security question because any security force which goes in there would be looked at with suspicion as though they’re propping up the current Haitian government,” the Western Hemisphere’s longest-serving political leader explained.

Gonsalves said that some countries instead favor a rapid response, not contingent on any political accord, and, he explained, those countries have been heavily lobbying CARICOM nations to get their support for such a mission. “Well, one thing I’ll tell you, St. Vincent and the Grenadines will not be sending any police in that situation because I don’t want anybody to interpret us as going to send the police there to help to prop up the government,” he said.

Though he did not mention any other countries by name, the reference is likely to the United States, which has remained a steadfast ally to Haiti’s de facto prime minister, Ariel Henry. While the US has been the most vocal proponent of a foreign-led security mission in Haiti, it has thus far refused to contribute its own personnel and has been persistently reaching out to other nations in the hope of finding a third party to take the lead. Those efforts have focused primarily on Canada, and included a visit to Ottawa by Secretary of State Antony Blinken last month.

Canada, while not explicitly rejecting the idea that it could lead such an intervention, has said it is considering its options. But, last week, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau publicly backed Gonsalves’s analysis.

“It is not enough for Haiti’s government to ask for it,” Trudeau said. “There needs to be a consensus across political parties in Haiti before we can move forward on more significant steps.” The Canadian leader once again said his country was open to participating in a military intervention, but that “we must have a Haitian consensus” first.

The US has approached a number of other countries about participating in such a mission, including Brazil, which led the last United Nations military force in Haiti, MINUSTAH, from 2004 to 2017. Diplomatic cables published by WikiLeaks reveal that, at the time, the US sought to find a third-party country to lead the UN mission as a way to save money and outsource its control over Haiti. “Without a UN-sanctioned peacekeeping and stabilization force, we would be getting far less help from our hemispheric and European partners in managing Haiti,” the then ambassador wrote in 2008.

But it appears Brazil has little appetite in returning to Haiti now. “Any Brazilian participation would be difficult, overall in a multinational force,” Celso Amorim, Brazil’s former foreign minister and a top advisor to president elect Lula da Silva, told Reuters. “We made an enormous effort that brought us a lot of problems, even internally,” he said.

Of course, obtaining UN authorization at all remains a question mark. China and Russia, who both hold veto power at the Security Council, have expressed skepticism. Last month, the Miami Herald reported that the US was “planning contingencies for a multilateral force that would enter Haiti without formal U.N. authorization,” though it is unclear if that could mean the deployment of US military assets.

What is clear, however, is that the US appears committed to at least some sort of foreign security intervention in Haiti. In closed-door meetings in recent weeks, US officials have repeatedly indicated their optimism that something will be done.

“No Strategic Clarity”

“We’re very supportive of something to be done for Haitian people,” Gonsalves, the St. Vincent & the Grenadines prime minister said. “But you have to learn properly the humanitarian, the security and the political. You can’t just link humanitarian and security and forget the political and there is a lot of tactical confusion because there is no strategic clarity.”

The military intervention was initially framed as a “rapid action force” that would help unblock the country’s main fuel terminal in Port-au-Prince and help to resolve the immediate humanitarian situation. “This resolution will propose a limited, carefully scoped” mission, Linda Thomas Greenfield, the US Ambassador to the UN, told the security council in mid-October.

However, more than a month has passed and the fuel terminal has been operational for two weeks. Meanwhile, the scope of a possible mission appears to have expanded.

“There continue to be longer-term challenges that an enabling force authorized by the UN Security Council would be able to help address,” State Department spokesperson Ned Price said, in response to a question about if the resumption of fuel deliveries had lessened the need for an intervention. Thomas Shannon, a former high ranking US diplomat, suggested that what Haiti really needs is a long-term “state-building” mission akin to U.S. efforts in Afghanistan.

After initially saying the plan would be ready by early November, last week, the Miami Herald reported that the US sees little hope for progressing its UN resolution over the holidays — pushing a potential timeline out until early in 2023. “A second U.S. official said that the plan is not dead, but that the formation of such an ambitious military mission would take time,” the Herald reported.

Nobody, it seems, has any idea what this military endeavor would actually look like. A spokesperson from the French embassy told Politico: “To date, the contours of this possible intervention force have yet to be specified.”

“The problem is that nobody really believes that you can restore order and leave quickly,” Richard Gowan of the International Crisis Group said earlier this month.

In 2004, following the February coup d’etat against Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the de facto government requested urgent foreign military assistance. The same day as Aristide was flown into exile, the Security Council authorized the deployment of a three-month multinational force led by the US and Canada. That, however, was always just a stop gap measure while longer-term preparations for the arrival of the UN Blue Helmets took place. That mission stayed for 13 years.

Though pitched to the world as a fine-tuned intervention only to help address a dire humanitarian situation, the US’ failure to find immediate support has revealed what has likely been the case all along: any military intervention is likely to morph into yet another long-term, foreign-led attempt at nation building in Haiti.

• HaitiHaitiInequalityLa DesigualdadLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.

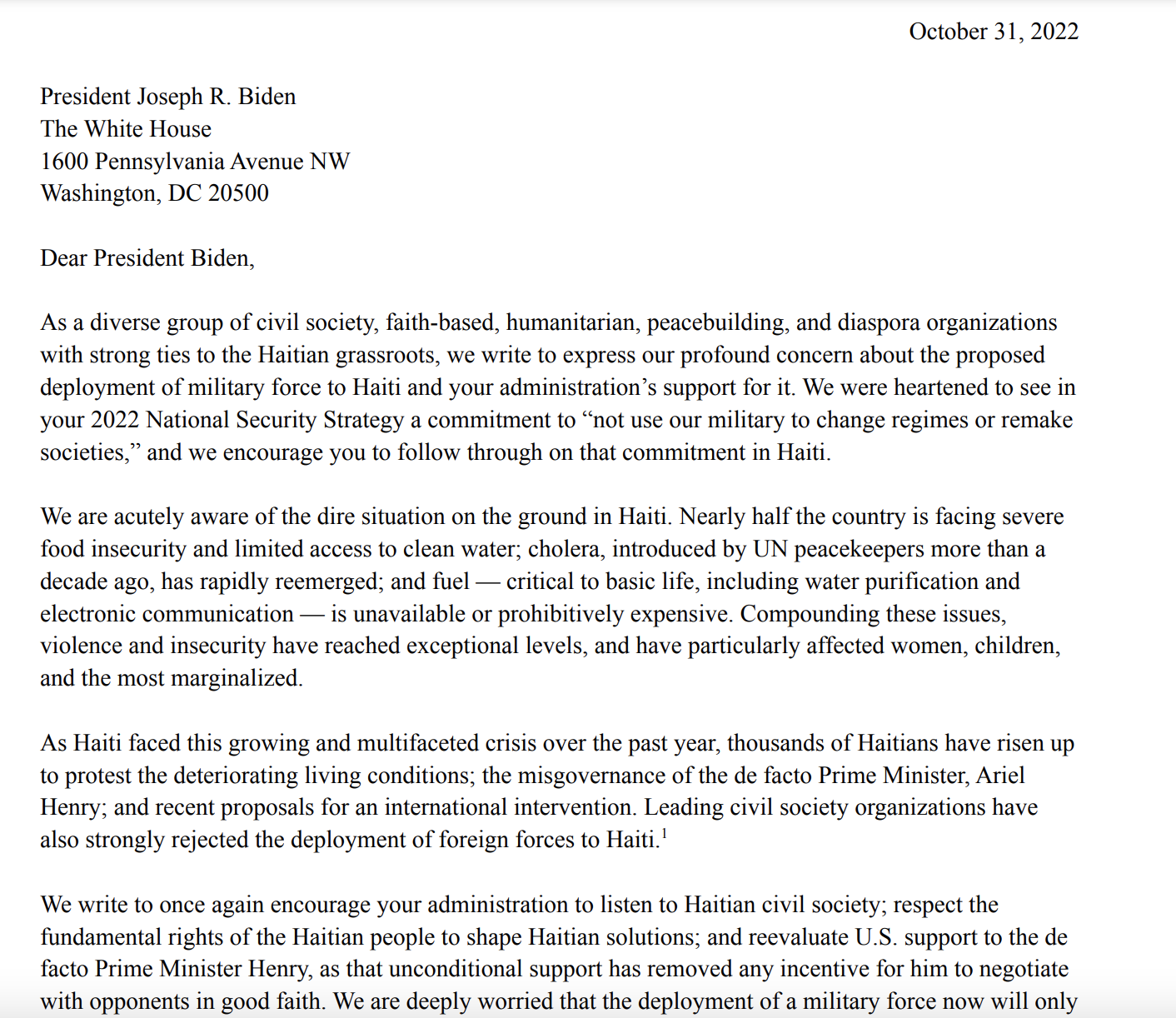

Today, more than 90 organizations sent a letter to US President Joe Biden expressing “profound concern about the proposed deployment of military force to Haiti.” The signers include faith-based, human rights, diaspora, and other civil society organizations with long-standing ties to Haiti. Prominent members of the peacebuilding community, including Win Without War and the Friends Committee on National Legislation, are also among the signers.*

Noting that many leading civil society organizations in Haiti have opposed calls for military intervention and that thousands of people have taken to the streets to denounce such a plan, the organizations urged the administration to “to reflect on the long history of international interventions in Haiti, and how those actions have served to undermine state institutions, democratic norms, and the rule of law.” The letter also notes that prior interventions had a costly human toll, resulting in rapes, sexual abuse, and extrajudicial killings.

The letter calls on the administration to listen to Haitian civil society, respect the rights of Haitians to shape their own solutions, and “reevaluate” its ongoing support for the de facto prime minister, Ariel Henry. “We are deeply worried that the deployment of a military force now will only perpetuate and strengthen Henry’s grasp on power, while doing little to ameliorate the root causes of today’s crisis.”

Rather than another military intervention, the groups urge the US administration to use “robust diplomacy” and to go beyond sanctions by pursuing criminal investigations into those actors — many of whom have interests in the US — that are stoking the violence in Haiti.

The signers also urged the administration, which had pushed the de facto Haitian authorities to remove fuel subsidies earlier this year, to reverse that decision. The elimination “deprived the most marginalized Haitians of the only concrete support their government had provided.”

“At the heart of the insecurity plaguing Haiti is the continuation of a political and economic system that excludes the vast majority of its citizenry. A long-term solution can only be achieved by addressing these underlying dynamics of inequality and exclusion and by providing for the population as a whole,” the organizations wrote.

To read the full text of the letter and the list of endorsing organizations, click here.

*The Center for Economic and Policy Research is one of the signing organizations.

Today, more than 90 organizations sent a letter to US President Joe Biden expressing “profound concern about the proposed deployment of military force to Haiti.” The signers include faith-based, human rights, diaspora, and other civil society organizations with long-standing ties to Haiti. Prominent members of the peacebuilding community, including Win Without War and the Friends Committee on National Legislation, are also among the signers.*

Noting that many leading civil society organizations in Haiti have opposed calls for military intervention and that thousands of people have taken to the streets to denounce such a plan, the organizations urged the administration to “to reflect on the long history of international interventions in Haiti, and how those actions have served to undermine state institutions, democratic norms, and the rule of law.” The letter also notes that prior interventions had a costly human toll, resulting in rapes, sexual abuse, and extrajudicial killings.

The letter calls on the administration to listen to Haitian civil society, respect the rights of Haitians to shape their own solutions, and “reevaluate” its ongoing support for the de facto prime minister, Ariel Henry. “We are deeply worried that the deployment of a military force now will only perpetuate and strengthen Henry’s grasp on power, while doing little to ameliorate the root causes of today’s crisis.”

Rather than another military intervention, the groups urge the US administration to use “robust diplomacy” and to go beyond sanctions by pursuing criminal investigations into those actors — many of whom have interests in the US — that are stoking the violence in Haiti.

The signers also urged the administration, which had pushed the de facto Haitian authorities to remove fuel subsidies earlier this year, to reverse that decision. The elimination “deprived the most marginalized Haitians of the only concrete support their government had provided.”

“At the heart of the insecurity plaguing Haiti is the continuation of a political and economic system that excludes the vast majority of its citizenry. A long-term solution can only be achieved by addressing these underlying dynamics of inequality and exclusion and by providing for the population as a whole,” the organizations wrote.

To read the full text of the letter and the list of endorsing organizations, click here.

*The Center for Economic and Policy Research is one of the signing organizations.

• HaitiHaitiLatin America and the CaribbeanAmérica Latina y el CaribeUS Foreign PolicyPolítica exterior de EE. UU.WorldEl Mundo

After nearly seven weeks of nationwide protests and amid a “catastrophic” humanitarian crisis, de facto prime minister Ariel Henry has officially requested the help of international military forces. If it were to happen, it would be only the latest in a long line of foreign military interventions in Haiti — interventions that, in many ways, helped to contribute to the current situation.

Crises have always been the ostensible impetus for military interventions in Haiti. In 1915, following a period of political instability and the assassination of President Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, US Marines landed in Haiti. They stayed for 19 years, instituting forced labor, choosing political leaders, drastically reshaping the nation, and killing those that resisted, like the peasantry.

Demonstrations against Henry’s rule, which had been building for some time already, were given new life after the early September announcement that the government was ending fuel subsidies, sending the already high cost of living up even further. At the same time, armed groups affiliated with Jimmy Chérizier, a former police officer and leader of the G9 Family and Allies, blockaded the Varreux Terminal in downtown Port-au-Prince, where the vast majority of the country’s fuel imports arrive. Since mid-September, there has been no distribution of fuel or other goods from Varreux, contributing to massive shortages. The cost of a gallon of gasoline has skyrocketed to $30 or $40, and in many parts of rural Haiti, it is even higher.

The lack of fuel has caused hospitals to close or ration care, banks, and supermarkets to limit their hours, and even the police to lessen their operations to unblock the terminal. In many of the popular neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince, clean drinking water is impossible to find — local shops that purify water cannot operate given, again, the lack of fuel. On top of all this, cholera — which killed tens of thousands of people after its 2010 introduction by United Nations troops and personnel (the last such foreign military intervention) — has reemerged, with Haiti registering its first case in nearly three years.

Violence and insecurity have reached unprecedented levels, with residents in many parts of not only the capital but across the country, unable to even leave their homes. Schools are closed. In addition to the G9 blockade of the fuel terminal, an ostensible rival conglomeration of armed groups known as G-Pep has seized territory in the south and north of Port-au-Prince, effectively choking the capital off from the rest of the country. Days after the Canadian ambassador suggested opening negotiations with the G9 on a humanitarian truce to allow fuel deliveries, a member of the G-Pep attacked and seized another port. Both groups are believed to have strong ties to members of Haiti’s political and economic elite.

Citing the humanitarian crisis, on October 6 de facto prime minister Henry formally requested the assistance of unspecified foreign militaries. The de facto authorities solicited “the immediate deployment of a specialized armed force, in sufficient quantity, to stop throughout the territory the humanitarian crisis caused by, among other things, the insecurity resulting from the criminal actions of armed gangs and their sponsors.”

The civil society-led Montana Group, which has been advocating for a transitional government to replace Henry, restore basic state functions, and eventually hold elections, quickly rejected the request, labeling it an act of “treason” and disavowing all forms of foreign intervention. The group claimed that Henry’s request was simply a desperate attempt by the leader to stay in power amid growing calls for his resignation.

Some aid groups have also raised concerns. “Our immediate reaction, as a medical organisation, is that this means more bullets, more injuries and more patients,” Benoît Vasseur, the director of Doctors Without Borders, whose clinics in Haiti serve many of those in areas controlled by armed groups, told The Guardian. “We are afraid there will be a lot of bloodshed.”

De facto prime minister Henry took office just weeks after last year’s assassination of President Jovenel Moïse — a crime he was later implicated in. The Core Group (made up of foreign embassies and international organizations) issued a public statement urging Henry, who was not in office during the assassination, to form a government. Within days, he did just that. However, after more than a year in office and with thousands taking to the streets protesting in favor of his resignation, his hold on power is tenuous at best. Yet he has retained the support of those same international actors.

Throughout September, high-level political negotiations were taking place, brokered by the UN office in Haiti, BINUH, on a “political accord” that could provide some legitimacy to the government. On October 3, an advisor to Henry went on local radio and declared that a deal was imminent and would be signed in the next couple of days. In only a matter of hours, that prospect dimmed, with opposition leaders publicly denouncing it before anything had even been signed. Notably, the Montana Group said it had been excluded from the negotiations altogether. The deal that had been on the table, backed by the international community, would have kept Henry in his position as prime minister.

Foreign diplomats hoped that the accord, despite keeping Henry in power, would at least provide a temporary reprieve and allow for the resumption of deliveries of basic goods like fuel. But, as the deal fell apart, the calls for foreign intervention quickly got louder.

On October 4, Canada’s ambassador to Haiti, Sébastien Carrière, tweeted that foreign embassies, the UN, and the OAS were “concerned” about the “humanitarian impact” of the blockade of Terminal Varreux and called “for an immediate humanitarian truce to allow the release of fuel for urgent needs.” The next day, BINUH issued an official statement calling “for the immediate opening of a humanitarian corridor to allow the release of fuel.”

On October 6, after meeting with the de facto Haitian government’s foreign minister and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken at the OAS General Assembly in Peru, the secretary general of the OAS, Luis Almagro, “called on Haiti to request urgent support from the international community to help solve [the] security crisis and determine [the] characteristics of the international security force.”

Within hours of Almagro’s tweet, the Miami Herald reported that Henry had asked his council of ministers to approve a formal request for foreign military assistance. That request was made official on October 7.

On October 9, Antonio Guterres, the secretary general of the United Nations, issued a statement urging “the international community, including the members of the Security Council, to consider as of matter of urgency the request by the Haitian Government for the immediate deployment of an international specialized armed force to address the humanitarian crisis.”

In Guterres’ letter to the Security Council, which outlined various security measures that could be taken, the UN leader suggested that such a force could be led by “one or several member states.” However, it also stated that “a return to a more robust United Nations engagement in the form of peacekeeping remains a last resort if no decisive action is urgently taken by the international community in line with the outlined options and national law enforcement capacity proves unable to reverse the deteriorating security situation.”

Two days later, on October 11, Haiti’s de facto ambassador to the US, Bocchit Edmond, made clear what they were really asking for. “We would … like to see a better and deeper involvement of the US in giving leadership to a strike force that will confront the armed gangs and work together with the Haitian National Police to restore law and order,” he told Bloomberg. “We wish to see our neighbors like the United States, like Canada, take the lead and move fast,” he told Reuters in a separate interview.

On October 12, the US dispatched its top diplomat for the Western Hemisphere, Brian Nichols, along with a high-ranking military official, to Haiti to meet with various stakeholders. At the request of the de facto authorities in Haiti, it also sent a Coast Guard cutter to patrol the waters off Port-au-Prince. The Biden administration has said it is “considering” the request from Henry but has offered no clear public support for a military intervention. “It’s premature to start thinking whether the United States is going to have a physical presence inside of Haiti,” an official told the press.

There are two points to consider about the Biden administration’s response to Henry’s request for troops. First, the US has made it clear that its preference is for another country (or group of countries) to be the face of any possible military intervention in Haiti. This was the strategy behind the largely Latin American composition of MINUSTAH — a force of 10,000 or so troops that was in Haiti following the US-backed 2004 coup up until 2017 — and remains the preference today. Second, the Biden administration is extremely unlikely to embark on any such military adventure in Haiti with just under four weeks before the US midterm elections.

Rather, the US strategy over the last month appears to have been to try and buy time with the threat of sanctions against those behind the violence in Haiti. The Biden administration, early on in the nationwide uprising, placed the blame on “economic actors who stand to lose money” from recent changes the de facto government made regarding customs. “These are people that often don’t even live in Haiti, who have mansions in different parts of the world, and are paying for people to go into the streets,” Juan Gonzalez, the National Security Council’s senior director for the Western Hemisphere, said at a September 19 public event. The comments set off a firestorm in Haiti, with activists and civil society leaders lambasting the remarks as undermining the legitimate peaceful protests taking place all over the country.

But Gonzalez was telegraphing where the administration was headed on its Haiti policy. “I don’t think anybody, including Haitians, wants to get to the point of having a return of a” United Nations peacekeeping force, he said. “So the question, short of that, is what is something we can do?”

The answer to that question came just a few days later. Nichols, the State Department diplomat, told the Miami Herald that the US was working on a UN Security Council resolution that would sanction “gang leaders” and others behind the violence. They “are in the crosshairs, and their actions to destabilize Haiti will be met with international travel and financial sanctions,” he said. Though the administration did not name any specific individuals, those familiar with the administration’s thinking explained that the hope was that raising the threat of sanctions would be enough to unblock the terminal, lessen the unrest, and convince perceived “bad actors” to stop working to undermine negotiations over a political accord.

After three-plus weeks, however, the situation had only deteriorated further — leading to the breakdown in political negotiations and Henry’s request for troops. Given the US’s public position, and the knowledge that the administration would be loath to take on such an effort in the run-up to elections, the actions of OAS Secretary General Almagro and the de facto Haitian authorities begin to look like a coordinated attempt to force a begrudging US into sending troops — or, perhaps more likely, to get the US to find some other country to do so.

The same day that Nichols and a top Defense Department official traveled to Haiti, the US announced it was placing visa restrictions on “Haitian officials and former government officials, and other individuals involved in the operation of street gangs and other Haitian criminal organizations that have threatened the livelihoods of the Haitian people and are blocking lifesaving humanitarian support.” In a background briefing for the press, an anonymous State Department official added that the US had also introduced its UN Security Council resolution on sanctions and were “negotiating with [council] members right now ahead of a vote.”

The US delegation also held meetings with both de facto prime minister Henry and with the leaders of the Montana Group, urging “political leaders in Haiti to put aside their differences to find a path toward sustainable peace.” With visas pulled, sanctions looming, and a possible military invasion being planned, however, any negotiations will be taking place with — as is so often the case — the heavy hands of the US and the international community looming over them.

On October 17, the UN Security Council is scheduled to meet to discuss the situation in Haiti; the meeting was actually moved up four days from its initial date. It is expected that topics will include both Henry’s request for troops and the US-drafted sanctions resolution. At a prior meeting, the council had also set mid-October as a deadline for the de facto Haitian authorities to report back on their efforts to reach a political accord. There will be tremendous pressure to reach such a deal in the coming days.

The rejection of Henry’s appeal for foreign troops extended far beyond the Montana Group. The 10 remaining Haitian senators (the rest of the parliamentarians’ terms expired years ago, and the body itself is not functional), also denounced it, as did many leading political figures and civil society organizations. There have also been large protests explicitly rejecting Henry’s request.

However, despite the long and negative history of foreign interventions in Haiti, it is not hard to find support for such an effort today. I asked a friend, a school teacher in Cité Soleil, what they thought about foreign troops. “It would be good for the people even though military interventions in Haiti haven’t ever given us good results,” he responded. It’s not hard to understand the sentiment.

With no security, no clean water, no fuel, and food that, even if available, is often too expensive for most to even purchase, there is no denying the magnitude of the situation on the ground. Even before the latest shutdown, more than four million Haitians were facing severe hunger. Now, stories of families going days without eating or drinking anything have become common. “Nou bezwen yon souf” has become a common refrain in Haiti — “We need a breath.” With a state that has abandoned and excluded the majority of the population, and who many see as ultimately behind the violence perpetrated by armed groups, many have little faith in a short-term local solution led by their own government or others among the traditional political class.

But, when I asked my friend if his opinion would change if the military intervened and Henry remained in power, his answer was just as clear. That, he explained, would be problematic. “Anything and everything bad could happen if they kept Henry in power,” he said.

While the talk of foreign troops has been framed almost exclusively as a response to the humanitarian situation, it is impossible to divorce such a mission from the nation’s politics. And while there is no doubt that government officials and members of the elite are funding much of the insecurity throughout the country, not all are working toward the same objective. Comments like those of the NSC’s Juan Gonzalez make it seem as if such actions are meant to undermine Henry, but in many ways, the violence and humanitarian crisis are playing right into the hands of Henry and other factions of the elite who also see their interests as threatened by the popular uprising. It would be naïve to think that certain actors are not stoking the crisis in order to justify a foreign intervention that, they believe, would protect the status quo — a brutally unequal status quo that lies at the root of the current situation.

It is during times of great upheaval that foreign powers have historically intervened in Haiti, in 1915, 1994, 2004, and 2010. But in each instance, the intervention ended up serving the interests of the US and a small local elite. Security is necessary, but security for whom? “Every time there’s intervention the same system stays in place,” Louis-Henri Mars, who runs a peacebuilding organization in Port-au-Prince, told The Guardian.

Now, if the international community does send troops to Haiti, the “legitimacy” of such an operation would stem from the authorization of Henry, making him an indispensable part of any political negotiation. Meanwhile, the urgency of the situation on the ground is putting added pressure on Henry’s opponents to make concessions part of any deal.

On October 13, the Associated Press obtained a copy of the US-backed resolution to be discussed in the coming days at the UN. In addition to sanctioning Chérizier, the G9 leader — who has already been under US sanctions since 2020 — the resolution “encourages ‘the immediate deployment of a multinational rapid action force’ to support the Haitian National Police.”

There are already conversations taking place about who would lead such a force and what its composition, mandate, and timing would really be. The specifics of the latest foreign military intervention in Haiti remain to be seen, but even putting it on the table appears to be serving the interests of those seeking to prop up an inherently unsustainable status quo.

After nearly seven weeks of nationwide protests and amid a “catastrophic” humanitarian crisis, de facto prime minister Ariel Henry has officially requested the help of international military forces. If it were to happen, it would be only the latest in a long line of foreign military interventions in Haiti — interventions that, in many ways, helped to contribute to the current situation.

Crises have always been the ostensible impetus for military interventions in Haiti. In 1915, following a period of political instability and the assassination of President Jean Vilbrun Guillaume Sam, US Marines landed in Haiti. They stayed for 19 years, instituting forced labor, choosing political leaders, drastically reshaping the nation, and killing those that resisted, like the peasantry.

Demonstrations against Henry’s rule, which had been building for some time already, were given new life after the early September announcement that the government was ending fuel subsidies, sending the already high cost of living up even further. At the same time, armed groups affiliated with Jimmy Chérizier, a former police officer and leader of the G9 Family and Allies, blockaded the Varreux Terminal in downtown Port-au-Prince, where the vast majority of the country’s fuel imports arrive. Since mid-September, there has been no distribution of fuel or other goods from Varreux, contributing to massive shortages. The cost of a gallon of gasoline has skyrocketed to $30 or $40, and in many parts of rural Haiti, it is even higher.

The lack of fuel has caused hospitals to close or ration care, banks, and supermarkets to limit their hours, and even the police to lessen their operations to unblock the terminal. In many of the popular neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince, clean drinking water is impossible to find — local shops that purify water cannot operate given, again, the lack of fuel. On top of all this, cholera — which killed tens of thousands of people after its 2010 introduction by United Nations troops and personnel (the last such foreign military intervention) — has reemerged, with Haiti registering its first case in nearly three years.

Violence and insecurity have reached unprecedented levels, with residents in many parts of not only the capital but across the country, unable to even leave their homes. Schools are closed. In addition to the G9 blockade of the fuel terminal, an ostensible rival conglomeration of armed groups known as G-Pep has seized territory in the south and north of Port-au-Prince, effectively choking the capital off from the rest of the country. Days after the Canadian ambassador suggested opening negotiations with the G9 on a humanitarian truce to allow fuel deliveries, a member of the G-Pep attacked and seized another port. Both groups are believed to have strong ties to members of Haiti’s political and economic elite.

Citing the humanitarian crisis, on October 6 de facto prime minister Henry formally requested the assistance of unspecified foreign militaries. The de facto authorities solicited “the immediate deployment of a specialized armed force, in sufficient quantity, to stop throughout the territory the humanitarian crisis caused by, among other things, the insecurity resulting from the criminal actions of armed gangs and their sponsors.”

The civil society-led Montana Group, which has been advocating for a transitional government to replace Henry, restore basic state functions, and eventually hold elections, quickly rejected the request, labeling it an act of “treason” and disavowing all forms of foreign intervention. The group claimed that Henry’s request was simply a desperate attempt by the leader to stay in power amid growing calls for his resignation.

Some aid groups have also raised concerns. “Our immediate reaction, as a medical organisation, is that this means more bullets, more injuries and more patients,” Benoît Vasseur, the director of Doctors Without Borders, whose clinics in Haiti serve many of those in areas controlled by armed groups, told The Guardian. “We are afraid there will be a lot of bloodshed.”

De facto prime minister Henry took office just weeks after last year’s assassination of President Jovenel Moïse — a crime he was later implicated in. The Core Group (made up of foreign embassies and international organizations) issued a public statement urging Henry, who was not in office during the assassination, to form a government. Within days, he did just that. However, after more than a year in office and with thousands taking to the streets protesting in favor of his resignation, his hold on power is tenuous at best. Yet he has retained the support of those same international actors.

Throughout September, high-level political negotiations were taking place, brokered by the UN office in Haiti, BINUH, on a “political accord” that could provide some legitimacy to the government. On October 3, an advisor to Henry went on local radio and declared that a deal was imminent and would be signed in the next couple of days. In only a matter of hours, that prospect dimmed, with opposition leaders publicly denouncing it before anything had even been signed. Notably, the Montana Group said it had been excluded from the negotiations altogether. The deal that had been on the table, backed by the international community, would have kept Henry in his position as prime minister.

Foreign diplomats hoped that the accord, despite keeping Henry in power, would at least provide a temporary reprieve and allow for the resumption of deliveries of basic goods like fuel. But, as the deal fell apart, the calls for foreign intervention quickly got louder.

On October 4, Canada’s ambassador to Haiti, Sébastien Carrière, tweeted that foreign embassies, the UN, and the OAS were “concerned” about the “humanitarian impact” of the blockade of Terminal Varreux and called “for an immediate humanitarian truce to allow the release of fuel for urgent needs.” The next day, BINUH issued an official statement calling “for the immediate opening of a humanitarian corridor to allow the release of fuel.”

On October 6, after meeting with the de facto Haitian government’s foreign minister and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken at the OAS General Assembly in Peru, the secretary general of the OAS, Luis Almagro, “called on Haiti to request urgent support from the international community to help solve [the] security crisis and determine [the] characteristics of the international security force.”

Within hours of Almagro’s tweet, the Miami Herald reported that Henry had asked his council of ministers to approve a formal request for foreign military assistance. That request was made official on October 7.

On October 9, Antonio Guterres, the secretary general of the United Nations, issued a statement urging “the international community, including the members of the Security Council, to consider as of matter of urgency the request by the Haitian Government for the immediate deployment of an international specialized armed force to address the humanitarian crisis.”

In Guterres’ letter to the Security Council, which outlined various security measures that could be taken, the UN leader suggested that such a force could be led by “one or several member states.” However, it also stated that “a return to a more robust United Nations engagement in the form of peacekeeping remains a last resort if no decisive action is urgently taken by the international community in line with the outlined options and national law enforcement capacity proves unable to reverse the deteriorating security situation.”

Two days later, on October 11, Haiti’s de facto ambassador to the US, Bocchit Edmond, made clear what they were really asking for. “We would … like to see a better and deeper involvement of the US in giving leadership to a strike force that will confront the armed gangs and work together with the Haitian National Police to restore law and order,” he told Bloomberg. “We wish to see our neighbors like the United States, like Canada, take the lead and move fast,” he told Reuters in a separate interview.

On October 12, the US dispatched its top diplomat for the Western Hemisphere, Brian Nichols, along with a high-ranking military official, to Haiti to meet with various stakeholders. At the request of the de facto authorities in Haiti, it also sent a Coast Guard cutter to patrol the waters off Port-au-Prince. The Biden administration has said it is “considering” the request from Henry but has offered no clear public support for a military intervention. “It’s premature to start thinking whether the United States is going to have a physical presence inside of Haiti,” an official told the press.

There are two points to consider about the Biden administration’s response to Henry’s request for troops. First, the US has made it clear that its preference is for another country (or group of countries) to be the face of any possible military intervention in Haiti. This was the strategy behind the largely Latin American composition of MINUSTAH — a force of 10,000 or so troops that was in Haiti following the US-backed 2004 coup up until 2017 — and remains the preference today. Second, the Biden administration is extremely unlikely to embark on any such military adventure in Haiti with just under four weeks before the US midterm elections.

Rather, the US strategy over the last month appears to have been to try and buy time with the threat of sanctions against those behind the violence in Haiti. The Biden administration, early on in the nationwide uprising, placed the blame on “economic actors who stand to lose money” from recent changes the de facto government made regarding customs. “These are people that often don’t even live in Haiti, who have mansions in different parts of the world, and are paying for people to go into the streets,” Juan Gonzalez, the National Security Council’s senior director for the Western Hemisphere, said at a September 19 public event. The comments set off a firestorm in Haiti, with activists and civil society leaders lambasting the remarks as undermining the legitimate peaceful protests taking place all over the country.

But Gonzalez was telegraphing where the administration was headed on its Haiti policy. “I don’t think anybody, including Haitians, wants to get to the point of having a return of a” United Nations peacekeeping force, he said. “So the question, short of that, is what is something we can do?”

The answer to that question came just a few days later. Nichols, the State Department diplomat, told the Miami Herald that the US was working on a UN Security Council resolution that would sanction “gang leaders” and others behind the violence. They “are in the crosshairs, and their actions to destabilize Haiti will be met with international travel and financial sanctions,” he said. Though the administration did not name any specific individuals, those familiar with the administration’s thinking explained that the hope was that raising the threat of sanctions would be enough to unblock the terminal, lessen the unrest, and convince perceived “bad actors” to stop working to undermine negotiations over a political accord.

After three-plus weeks, however, the situation had only deteriorated further — leading to the breakdown in political negotiations and Henry’s request for troops. Given the US’s public position, and the knowledge that the administration would be loath to take on such an effort in the run-up to elections, the actions of OAS Secretary General Almagro and the de facto Haitian authorities begin to look like a coordinated attempt to force a begrudging US into sending troops — or, perhaps more likely, to get the US to find some other country to do so.

The same day that Nichols and a top Defense Department official traveled to Haiti, the US announced it was placing visa restrictions on “Haitian officials and former government officials, and other individuals involved in the operation of street gangs and other Haitian criminal organizations that have threatened the livelihoods of the Haitian people and are blocking lifesaving humanitarian support.” In a background briefing for the press, an anonymous State Department official added that the US had also introduced its UN Security Council resolution on sanctions and were “negotiating with [council] members right now ahead of a vote.”

The US delegation also held meetings with both de facto prime minister Henry and with the leaders of the Montana Group, urging “political leaders in Haiti to put aside their differences to find a path toward sustainable peace.” With visas pulled, sanctions looming, and a possible military invasion being planned, however, any negotiations will be taking place with — as is so often the case — the heavy hands of the US and the international community looming over them.

On October 17, the UN Security Council is scheduled to meet to discuss the situation in Haiti; the meeting was actually moved up four days from its initial date. It is expected that topics will include both Henry’s request for troops and the US-drafted sanctions resolution. At a prior meeting, the council had also set mid-October as a deadline for the de facto Haitian authorities to report back on their efforts to reach a political accord. There will be tremendous pressure to reach such a deal in the coming days.

The rejection of Henry’s appeal for foreign troops extended far beyond the Montana Group. The 10 remaining Haitian senators (the rest of the parliamentarians’ terms expired years ago, and the body itself is not functional), also denounced it, as did many leading political figures and civil society organizations. There have also been large protests explicitly rejecting Henry’s request.

However, despite the long and negative history of foreign interventions in Haiti, it is not hard to find support for such an effort today. I asked a friend, a school teacher in Cité Soleil, what they thought about foreign troops. “It would be good for the people even though military interventions in Haiti haven’t ever given us good results,” he responded. It’s not hard to understand the sentiment.

With no security, no clean water, no fuel, and food that, even if available, is often too expensive for most to even purchase, there is no denying the magnitude of the situation on the ground. Even before the latest shutdown, more than four million Haitians were facing severe hunger. Now, stories of families going days without eating or drinking anything have become common. “Nou bezwen yon souf” has become a common refrain in Haiti — “We need a breath.” With a state that has abandoned and excluded the majority of the population, and who many see as ultimately behind the violence perpetrated by armed groups, many have little faith in a short-term local solution led by their own government or others among the traditional political class.

But, when I asked my friend if his opinion would change if the military intervened and Henry remained in power, his answer was just as clear. That, he explained, would be problematic. “Anything and everything bad could happen if they kept Henry in power,” he said.

While the talk of foreign troops has been framed almost exclusively as a response to the humanitarian situation, it is impossible to divorce such a mission from the nation’s politics. And while there is no doubt that government officials and members of the elite are funding much of the insecurity throughout the country, not all are working toward the same objective. Comments like those of the NSC’s Juan Gonzalez make it seem as if such actions are meant to undermine Henry, but in many ways, the violence and humanitarian crisis are playing right into the hands of Henry and other factions of the elite who also see their interests as threatened by the popular uprising. It would be naïve to think that certain actors are not stoking the crisis in order to justify a foreign intervention that, they believe, would protect the status quo — a brutally unequal status quo that lies at the root of the current situation.

It is during times of great upheaval that foreign powers have historically intervened in Haiti, in 1915, 1994, 2004, and 2010. But in each instance, the intervention ended up serving the interests of the US and a small local elite. Security is necessary, but security for whom? “Every time there’s intervention the same system stays in place,” Louis-Henri Mars, who runs a peacebuilding organization in Port-au-Prince, told The Guardian.

Now, if the international community does send troops to Haiti, the “legitimacy” of such an operation would stem from the authorization of Henry, making him an indispensable part of any political negotiation. Meanwhile, the urgency of the situation on the ground is putting added pressure on Henry’s opponents to make concessions part of any deal.

On October 13, the Associated Press obtained a copy of the US-backed resolution to be discussed in the coming days at the UN. In addition to sanctioning Chérizier, the G9 leader — who has already been under US sanctions since 2020 — the resolution “encourages ‘the immediate deployment of a multinational rapid action force’ to support the Haitian National Police.”

There are already conversations taking place about who would lead such a force and what its composition, mandate, and timing would really be. The specifics of the latest foreign military intervention in Haiti remain to be seen, but even putting it on the table appears to be serving the interests of those seeking to prop up an inherently unsustainable status quo.