That is undoubtedly what readers are asking after seeing the headline, “Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg struggles to balance truth and free speech.” The headline is for the recording of a remarkably uncritical interview of Zuckerberg.

In the interview, Zuckerberg presents himself as struggling to deal with the trade-off between banning ads that are untrue and allowing free speech. If a reporter had been conducting the interview, they would have pointed out that every newspaper in the country faces the same problem and, unlike Zuckerberg, seem capable of dealing with it.

They will not print ads that they know to be untrue and, if they are shown evidence that an ad is untruthful after it runs, they typically will run a correction. It would have been useful to point this out to readers.

That is undoubtedly what readers are asking after seeing the headline, “Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg struggles to balance truth and free speech.” The headline is for the recording of a remarkably uncritical interview of Zuckerberg.

In the interview, Zuckerberg presents himself as struggling to deal with the trade-off between banning ads that are untrue and allowing free speech. If a reporter had been conducting the interview, they would have pointed out that every newspaper in the country faces the same problem and, unlike Zuckerberg, seem capable of dealing with it.

They will not print ads that they know to be untrue and, if they are shown evidence that an ad is untruthful after it runs, they typically will run a correction. It would have been useful to point this out to readers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It made this assertion in two different articles last week, without attributing it to a source. The budget data from the I.M.F. do not seem to support this claim. (The numbers are all percent of GDP.)

While the deficits run in 2015 and 2016 were unsustainable, the deficit came down sharply in the next two years. The deficit run in 2018 and projected for 2019 could be sustained indefinitely. (Ecuador uses the dollar as its currency, so it must be able to borrow the money needed to finance its deficit in financial markets.)

|

Subject Descriptor |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

General government net lending/borrowing |

-6.119 |

-8.232 |

-4.533 |

-0.949 |

0.022 |

|

General government structural balance |

-6.714 |

-6.783 |

-4.020 |

-1.676 |

-0.012 |

|

General government primary net lending/borrowing |

-4.688 |

-6.670 |

-2.415 |

1.541 |

2.659 |

|

General government gross debt |

33.798 |

43.166 |

44.617 |

46.132 |

49.199 |

It made this assertion in two different articles last week, without attributing it to a source. The budget data from the I.M.F. do not seem to support this claim. (The numbers are all percent of GDP.)

While the deficits run in 2015 and 2016 were unsustainable, the deficit came down sharply in the next two years. The deficit run in 2018 and projected for 2019 could be sustained indefinitely. (Ecuador uses the dollar as its currency, so it must be able to borrow the money needed to finance its deficit in financial markets.)

|

Subject Descriptor |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

|

General government net lending/borrowing |

-6.119 |

-8.232 |

-4.533 |

-0.949 |

0.022 |

|

General government structural balance |

-6.714 |

-6.783 |

-4.020 |

-1.676 |

-0.012 |

|

General government primary net lending/borrowing |

-4.688 |

-6.670 |

-2.415 |

1.541 |

2.659 |

|

General government gross debt |

33.798 |

43.166 |

44.617 |

46.132 |

49.199 |

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That seemed to be what Zuckerberg was saying in an interview with the Washington Post. Zuckerberg responding to complaints that Facebook was allowing people to lie in political ads:

“‘People worry, and I worry deeply, too, about an erosion of truth,’ Zuckerberg told The Washington Post ahead of a speech Thursday at Georgetown University. ‘At the same time, I don’t think people want to live in a world where you can only say things that tech companies decide are 100 percent true. And I think that those tensions are something we have to live with.'”

Zuckerberg apparently feels tech companies lack the competence to determine the truth of claims that people make in ads and elsewhere. Traditional publishers make this determination all the time. They refuse ads that they believe to be false and issue corrections for ads that they run and then later are presented with proof that the ads are false.

It may well be the case that Facebook is run by incompetents, but that is an argument for improving the quality of its staffing, not allowing it to be a medium for spreading lies.

That seemed to be what Zuckerberg was saying in an interview with the Washington Post. Zuckerberg responding to complaints that Facebook was allowing people to lie in political ads:

“‘People worry, and I worry deeply, too, about an erosion of truth,’ Zuckerberg told The Washington Post ahead of a speech Thursday at Georgetown University. ‘At the same time, I don’t think people want to live in a world where you can only say things that tech companies decide are 100 percent true. And I think that those tensions are something we have to live with.'”

Zuckerberg apparently feels tech companies lack the competence to determine the truth of claims that people make in ads and elsewhere. Traditional publishers make this determination all the time. They refuse ads that they believe to be false and issue corrections for ads that they run and then later are presented with proof that the ads are false.

It may well be the case that Facebook is run by incompetents, but that is an argument for improving the quality of its staffing, not allowing it to be a medium for spreading lies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

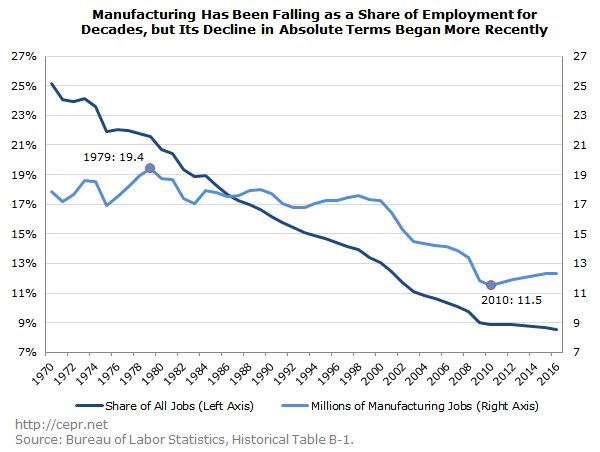

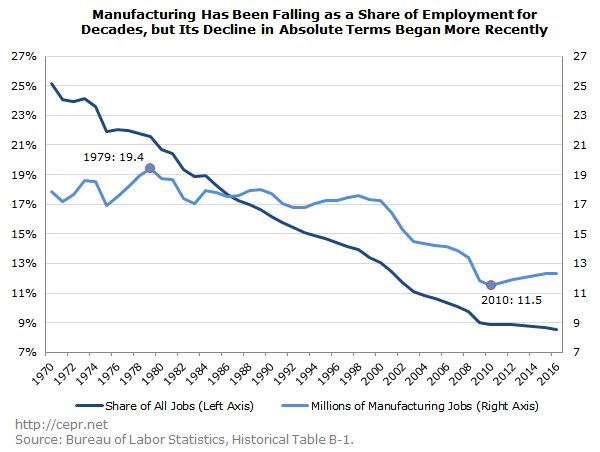

It is amazing how reporters and many economists feel the need to deceive the public about the reason for the loss of manufacturing jobs in the last decade. The number of manufacturing jobs was little changed from 1970 to 2000. From 2000 to the end of 2007 (before the Great Recession) we lost 3.4 million manufacturing jobs as the trade deficit exploded.

Fans of logic and arithmetic might think there is a connection there, the AP’s Fact Checker apparently does not. It tells readers:

“On trade

ELIZABETH WARREN: “The data show that we’ve had a lot of problems with losing jobs, but the principal reason has been bad trade policy. The principal reason has been a bunch of corporations, giant multinational corporations who’ve been calling the shots on trade.”

THE FACTS: Economists mostly blame those job losses on automation and robots, not trade deals.

So the Massachusetts senator is off.”

Here’s the picture as of a few years ago (sorry, I’m too lazy to update it).

Apart from the huge falloff in the years from 2000 to 2007, which continued with the Great Recession, it is also interesting to note that manufacturing employment stabilized, and has risen modestly in the years since the Great Recession. So the economists AP relies on as sources much believe that robots and automation stopped displacing workers in manufacturing some time in 2010. Alternatively, we might note that the trade deficit has stabilized in the last nine years.

It is amazing how reporters and many economists feel the need to deceive the public about the reason for the loss of manufacturing jobs in the last decade. The number of manufacturing jobs was little changed from 1970 to 2000. From 2000 to the end of 2007 (before the Great Recession) we lost 3.4 million manufacturing jobs as the trade deficit exploded.

Fans of logic and arithmetic might think there is a connection there, the AP’s Fact Checker apparently does not. It tells readers:

“On trade

ELIZABETH WARREN: “The data show that we’ve had a lot of problems with losing jobs, but the principal reason has been bad trade policy. The principal reason has been a bunch of corporations, giant multinational corporations who’ve been calling the shots on trade.”

THE FACTS: Economists mostly blame those job losses on automation and robots, not trade deals.

So the Massachusetts senator is off.”

Here’s the picture as of a few years ago (sorry, I’m too lazy to update it).

Apart from the huge falloff in the years from 2000 to 2007, which continued with the Great Recession, it is also interesting to note that manufacturing employment stabilized, and has risen modestly in the years since the Great Recession. So the economists AP relies on as sources much believe that robots and automation stopped displacing workers in manufacturing some time in 2010. Alternatively, we might note that the trade deficit has stabilized in the last nine years.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a piece on U.S. Internet regulations, and efforts to apply them to other countries, that may have left some readers confused. The piece focused on Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which protects Internet intermediaries from many of the liabilities faced by conventional publishers.

Perhaps the most important one of these liabilities is exposure to libel law. In the case of standard publishers, if a publisher helps to spread a third party’s libelous claim, then they can be sued for libel. For example, if Rudy Giuliani writes a column in the NYT saying that Joe Biden killed his neighbor, it can be held responsible if Biden presents it with clear evidence that he didn’t kill his neighbor and it makes no effort to correct the libelous information.

By contrast, under Section 230, if Giuliani makes and spreads this claim through Facebook, Biden has no ability to sue Mark Zuckerberg, even if he introduces Zuckerberg to his still living neighbor. It is not clear why an Internet intermediary should enjoy immunity for spreading libelous claims that neither a print nor broadcast outlet have.

The NYT had a piece on U.S. Internet regulations, and efforts to apply them to other countries, that may have left some readers confused. The piece focused on Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which protects Internet intermediaries from many of the liabilities faced by conventional publishers.

Perhaps the most important one of these liabilities is exposure to libel law. In the case of standard publishers, if a publisher helps to spread a third party’s libelous claim, then they can be sued for libel. For example, if Rudy Giuliani writes a column in the NYT saying that Joe Biden killed his neighbor, it can be held responsible if Biden presents it with clear evidence that he didn’t kill his neighbor and it makes no effort to correct the libelous information.

By contrast, under Section 230, if Giuliani makes and spreads this claim through Facebook, Biden has no ability to sue Mark Zuckerberg, even if he introduces Zuckerberg to his still living neighbor. It is not clear why an Internet intermediary should enjoy immunity for spreading libelous claims that neither a print nor broadcast outlet have.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I was struck by a New York Times article on the disruptions within the corporate hierarchy at Nissan, the huge Japanese automaker. The article begins:

“An outside law firm investigating problems at Nissan, the troubled Japanese automaker, this summer discovered some potentially explosive information.

“Hari Nada, a powerful Nissan insider who was behind the ouster last year of Nissan’s chairman, Carlos Ghosn, over compensation issues, had been improperly overpaid himself, the firm found. A second insider involved in the corporate coup was responsible, the firm said, and had briefed Mr. Nada on what he had done.”

Reading on we discover:

“Mr. Nada, the head of Nissan’s legal department and security office, had in 2017 received about $280,000 in ‘unjust enrichment,’ the firm found.”

It also turns out that Hiroto Saikawa, the successor to Ghosn as CEO, had gotten $440,000 in compensation to which he was not entitled.

It is hard not to be struck by the small size of the payments that form the basis of this scandal. To be clear, this is real money, and in any case, top executives should not be stealing from the companies they manage.

But for comparison, consider the case of John Stumpf, the CEO of Wells Fargo. Mr. Stumpf was at the center of a fake account scandal where the bank created millions of fake accounts, presumably as part of an effort to boost its stock price. In spite of being the person overseeing this massive scandal, Stumpf walked away with $130 million, an amount that is almost 300 times the size of the improper payments that got Mr. Saikawa fired and more than 400 times the payments to Mr. Nada.

Clearly there are some differences between the United States and Japan on the accountability of CEOs and top management.

I was struck by a New York Times article on the disruptions within the corporate hierarchy at Nissan, the huge Japanese automaker. The article begins:

“An outside law firm investigating problems at Nissan, the troubled Japanese automaker, this summer discovered some potentially explosive information.

“Hari Nada, a powerful Nissan insider who was behind the ouster last year of Nissan’s chairman, Carlos Ghosn, over compensation issues, had been improperly overpaid himself, the firm found. A second insider involved in the corporate coup was responsible, the firm said, and had briefed Mr. Nada on what he had done.”

Reading on we discover:

“Mr. Nada, the head of Nissan’s legal department and security office, had in 2017 received about $280,000 in ‘unjust enrichment,’ the firm found.”

It also turns out that Hiroto Saikawa, the successor to Ghosn as CEO, had gotten $440,000 in compensation to which he was not entitled.

It is hard not to be struck by the small size of the payments that form the basis of this scandal. To be clear, this is real money, and in any case, top executives should not be stealing from the companies they manage.

But for comparison, consider the case of John Stumpf, the CEO of Wells Fargo. Mr. Stumpf was at the center of a fake account scandal where the bank created millions of fake accounts, presumably as part of an effort to boost its stock price. In spite of being the person overseeing this massive scandal, Stumpf walked away with $130 million, an amount that is almost 300 times the size of the improper payments that got Mr. Saikawa fired and more than 400 times the payments to Mr. Nada.

Clearly there are some differences between the United States and Japan on the accountability of CEOs and top management.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Wall Street Journal ran a lengthy piece on how bond rating agencies are again giving inflated ratings, in this case to collateralized loan obligations that include tranches of a variety of bonds and loans. Inflated ratings were a major problem in the housing bubble years, with the major rating agencies giving investment-grade ratings to mortgage-backed securities that were filled with subprime mortgages.

The piece notes the basic incentive problem that the issuer pays the rating agency. This gives rating agencies an incentive to give higher ratings as a way to attract business.

There actually is a simple solution to this incentive problem: have a third party pick the rating agency. Senator Al Franken proposed an amendment to the Dodd-Frank bill that would have had the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) pick rating agencies rather than issuers. The amendment passed the Senate with 65 votes, getting strong bi-partisan support.

Under this provision, if JP Morgan wanted to have a new issue rated, instead of calling Moody’s or Standard and Poor, it would call the SEC, which would then decide which agency should do the rating. This means that rating agencies would have no incentive to inflate ratings to gain customers.

In spite of the strong bipartisan support in the Senate, then-Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner did not want the provision to be included in the bill. As he boasts in his autobiography, he arranged to have it killed in the House-Senate conference.

So, when we see the problem of inflated bond ratings re-emerging, we should all be saying “Thank you, Secretary Geithner.”

The Wall Street Journal ran a lengthy piece on how bond rating agencies are again giving inflated ratings, in this case to collateralized loan obligations that include tranches of a variety of bonds and loans. Inflated ratings were a major problem in the housing bubble years, with the major rating agencies giving investment-grade ratings to mortgage-backed securities that were filled with subprime mortgages.

The piece notes the basic incentive problem that the issuer pays the rating agency. This gives rating agencies an incentive to give higher ratings as a way to attract business.

There actually is a simple solution to this incentive problem: have a third party pick the rating agency. Senator Al Franken proposed an amendment to the Dodd-Frank bill that would have had the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) pick rating agencies rather than issuers. The amendment passed the Senate with 65 votes, getting strong bi-partisan support.

Under this provision, if JP Morgan wanted to have a new issue rated, instead of calling Moody’s or Standard and Poor, it would call the SEC, which would then decide which agency should do the rating. This means that rating agencies would have no incentive to inflate ratings to gain customers.

In spite of the strong bipartisan support in the Senate, then-Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner did not want the provision to be included in the bill. As he boasts in his autobiography, he arranged to have it killed in the House-Senate conference.

So, when we see the problem of inflated bond ratings re-emerging, we should all be saying “Thank you, Secretary Geithner.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión