Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That point was missing from this NYT piece on how Trump’s trade deal gives into a number of longstanding Democratic demands on labor issues. While promoting workers’ rights in Mexico is a positive part of the new NAFTA, this is likely to have less long-term impact on both the United States and Mexico than rules that further strengthen and lengthen patent and copyright monopolies.

The new deal also limits governments’ abilities to regulate companies like Facebook and Google. Since the new NAFTA is likely to provide a framework for other trade deals, the provisions on intellectual property claims and restrictions on regulating the digital economy are the most important aspects of the new pact.

That point was missing from this NYT piece on how Trump’s trade deal gives into a number of longstanding Democratic demands on labor issues. While promoting workers’ rights in Mexico is a positive part of the new NAFTA, this is likely to have less long-term impact on both the United States and Mexico than rules that further strengthen and lengthen patent and copyright monopolies.

The new deal also limits governments’ abilities to regulate companies like Facebook and Google. Since the new NAFTA is likely to provide a framework for other trade deals, the provisions on intellectual property claims and restrictions on regulating the digital economy are the most important aspects of the new pact.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post gave readers the official story about NAFTA, diverging seriously from reality, in a piece on the status of negotiations on the new NAFTA. The piece tells readers:

“NAFTA was meant to expand trade among the United States, Canada and Mexico by removing tariffs and other barriers on products as they were shipped between countries. The pact did open up trade, but it also proved disruptive in terms of creating new manufacturing supply chains and relocating businesses and jobs.”

This implies that the disruption in terms of shifting jobs to Mexico to take advantage of low wage labor was an accidental outcome. In fact, this was a main point of the deal, as was widely noted by economists at the time. Proponents of the deal argued that it was necessary for U.S. manufacturers to have access to low-cost labor in Mexico to remain competitive internationally. No one who followed the debate at the time should have been in the least surprised by the loss of high paying union manufacturing jobs to Mexico, that is exactly the result that NAFTA was designed for.

NAFTA also did nothing to facilitate trade in highly paid professional services, such as those provided by doctors and dentists. This is because doctors and dentists are far more powerful politically than autoworkers.

It is also wrong to say that NAFTA was about expanding trade by removing barriers. A major feature of NAFTA was the requirement that Mexico strengthen and lengthen its patent and copyright protections. These barriers are 180 degrees at odds with expanding trade and removing barriers.

It is noteworthy that the new deal expands these barriers further. The Trump administration likely intends these provisions to be a model for other trade pacts, just as the rules on patents and copyrights were later put into other trade deals.

The new NAFTA will also make it more difficult for the member countries to regulate Facebook and other Internet giants. This is likely to make it easier for Mark Zuckerberg to spread fake news.

The Washington Post gave readers the official story about NAFTA, diverging seriously from reality, in a piece on the status of negotiations on the new NAFTA. The piece tells readers:

“NAFTA was meant to expand trade among the United States, Canada and Mexico by removing tariffs and other barriers on products as they were shipped between countries. The pact did open up trade, but it also proved disruptive in terms of creating new manufacturing supply chains and relocating businesses and jobs.”

This implies that the disruption in terms of shifting jobs to Mexico to take advantage of low wage labor was an accidental outcome. In fact, this was a main point of the deal, as was widely noted by economists at the time. Proponents of the deal argued that it was necessary for U.S. manufacturers to have access to low-cost labor in Mexico to remain competitive internationally. No one who followed the debate at the time should have been in the least surprised by the loss of high paying union manufacturing jobs to Mexico, that is exactly the result that NAFTA was designed for.

NAFTA also did nothing to facilitate trade in highly paid professional services, such as those provided by doctors and dentists. This is because doctors and dentists are far more powerful politically than autoworkers.

It is also wrong to say that NAFTA was about expanding trade by removing barriers. A major feature of NAFTA was the requirement that Mexico strengthen and lengthen its patent and copyright protections. These barriers are 180 degrees at odds with expanding trade and removing barriers.

It is noteworthy that the new deal expands these barriers further. The Trump administration likely intends these provisions to be a model for other trade pacts, just as the rules on patents and copyrights were later put into other trade deals.

The new NAFTA will also make it more difficult for the member countries to regulate Facebook and other Internet giants. This is likely to make it easier for Mark Zuckerberg to spread fake news.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post reported that birthrates hit their lowest level in more than three decades in 2018. It then told us why this could be bad news for the country:

“Keeping the number of births within a certain range, called the “replacement level,” ensures the population level will remain stable. A low birthrate runs the risk that the country will not be able to replace the workforce and have enough tax revenue, while a high birthrate can cause shortages of resources.”

That’s an interesting story, but productivity growth, even at slow rates, swamps the impact of demographic changes on the need for labor. Even a modest rate of productivity growth (e.g. 1.5 percent annually) means that we would need one third fewer workers to get the same output twenty years from now as we do today. This would dwarf the effect of any plausible shrinkage in the size of the workforce due to a smaller population. Such shrinkage could also be easily offset by immigration if we choose.

It is also worth noting that a regular theme in economic reporting is that robots are taking all the jobs. This is not true as the productivity data clearly show, but if it were true, then the last thing we would need to be concerned about is a shrinking workforce.

Finally, as a practical matter, a shrinking population will reduce strains on resources, as in making it easier to limit global warming, for those familiar with the issue. It is difficult to see a downside to a smaller population.

(Yes, we should have the supports to give people the option to have children. That is a different issue. They should have the right to have kids, but we don’t need their children.)

The Washington Post reported that birthrates hit their lowest level in more than three decades in 2018. It then told us why this could be bad news for the country:

“Keeping the number of births within a certain range, called the “replacement level,” ensures the population level will remain stable. A low birthrate runs the risk that the country will not be able to replace the workforce and have enough tax revenue, while a high birthrate can cause shortages of resources.”

That’s an interesting story, but productivity growth, even at slow rates, swamps the impact of demographic changes on the need for labor. Even a modest rate of productivity growth (e.g. 1.5 percent annually) means that we would need one third fewer workers to get the same output twenty years from now as we do today. This would dwarf the effect of any plausible shrinkage in the size of the workforce due to a smaller population. Such shrinkage could also be easily offset by immigration if we choose.

It is also worth noting that a regular theme in economic reporting is that robots are taking all the jobs. This is not true as the productivity data clearly show, but if it were true, then the last thing we would need to be concerned about is a shrinking workforce.

Finally, as a practical matter, a shrinking population will reduce strains on resources, as in making it easier to limit global warming, for those familiar with the issue. It is difficult to see a downside to a smaller population.

(Yes, we should have the supports to give people the option to have children. That is a different issue. They should have the right to have kids, but we don’t need their children.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That would have been worth mentioning in a piece discussing a new organization dedicated to reining in Amazon. Through much of its existence Amazon did not collect sales tax in most states.

As this became more contentious and it had a physical presence in more states, Amazon eventually agreed to start collecting sales taxes in all states. However, it still does not collect sales taxes on the sales of its affiliates, who account for more than 40 percent of the sales through Amazon’s site.

This is a massive subsidy with literally no policy rationale. In effect, the government is subsidizing purchases through Amazon at the expense of brick and mortar stores, many of which are small businesses. This policy is costing state and local governments billions of dollars in revenue and helping Amazon to grow at the expense of its competitors.

That would have been worth mentioning in a piece discussing a new organization dedicated to reining in Amazon. Through much of its existence Amazon did not collect sales tax in most states.

As this became more contentious and it had a physical presence in more states, Amazon eventually agreed to start collecting sales taxes in all states. However, it still does not collect sales taxes on the sales of its affiliates, who account for more than 40 percent of the sales through Amazon’s site.

This is a massive subsidy with literally no policy rationale. In effect, the government is subsidizing purchases through Amazon at the expense of brick and mortar stores, many of which are small businesses. This policy is costing state and local governments billions of dollars in revenue and helping Amazon to grow at the expense of its competitors.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

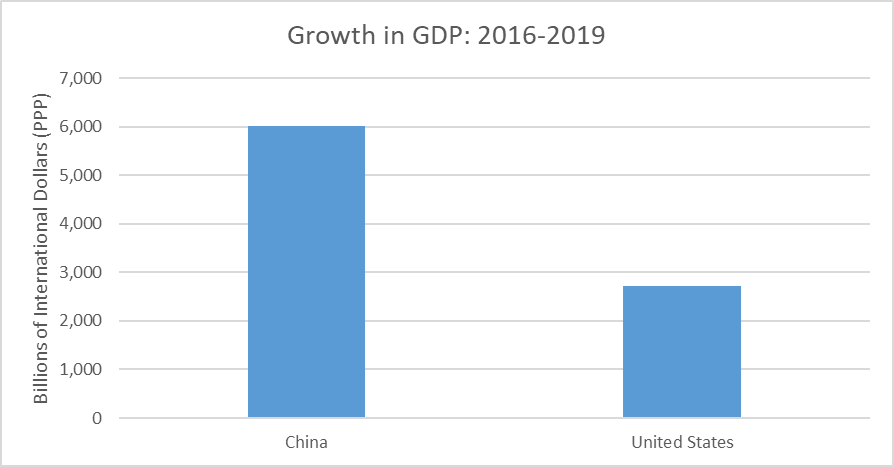

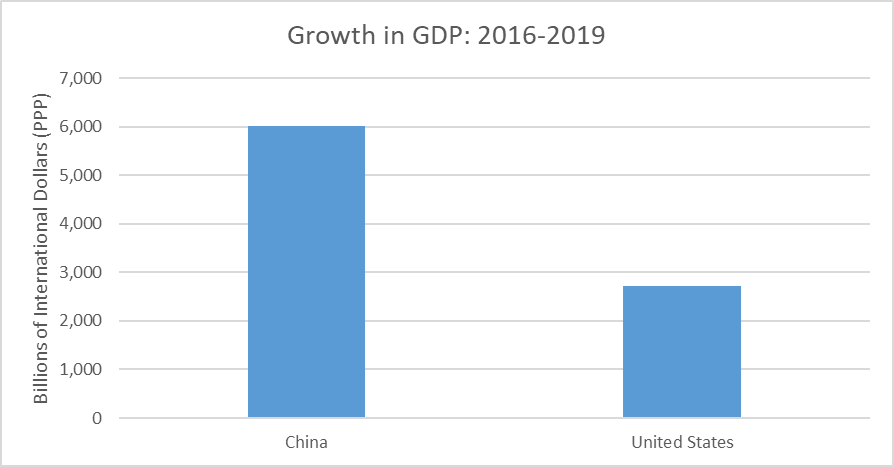

This is one in the “whose is bigger?” category; which country has added the most to their GDP over the last three years. There is not any particular reason anyone should care about this, except that Donald Trump has made a big point of touting something about how no one says China will soon be the world’s largest economy anymore.

In fact, China’s economy surpassed the U.S. economy in 2015, using the purchasing power parity measure of GDP. This measure, in principle, uses a common set of prices for all goods and services for all countries’ output. Most economists consider it the best measure of the size of a country’s economy for most purposes.

China has continued to grow much faster the United States, meaning the gap between the economies is growing. China’s economy is currently more than 25 percent larger than the U.S. economy.

The graph below shows the growth in the two countries’ economies since 2016.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

As can be seen, China’s growth has been more than twice as large as the growth in the United States since Donald Trump came into the White House. In other words, we should put Donald Trump’s claim that his policies have somehow secured the United States’ status as the world’s leading economy alongside his copy of President Obama’s Kenyan birth certificate.

This is one in the “whose is bigger?” category; which country has added the most to their GDP over the last three years. There is not any particular reason anyone should care about this, except that Donald Trump has made a big point of touting something about how no one says China will soon be the world’s largest economy anymore.

In fact, China’s economy surpassed the U.S. economy in 2015, using the purchasing power parity measure of GDP. This measure, in principle, uses a common set of prices for all goods and services for all countries’ output. Most economists consider it the best measure of the size of a country’s economy for most purposes.

China has continued to grow much faster the United States, meaning the gap between the economies is growing. China’s economy is currently more than 25 percent larger than the U.S. economy.

The graph below shows the growth in the two countries’ economies since 2016.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

As can be seen, China’s growth has been more than twice as large as the growth in the United States since Donald Trump came into the White House. In other words, we should put Donald Trump’s claim that his policies have somehow secured the United States’ status as the world’s leading economy alongside his copy of President Obama’s Kenyan birth certificate.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I have a lot of respect for Tim Wu, who has done much valuable work on concentration in the tech sector. However, when I saw his NYT piece on the death of the local hardware store I was somewhat skeptical. Most immediately, my experience with my thriving local hardware store (which gives great service, if any readers make it to Kanab) is 180 degrees at odds with his experience with his local hardware story in New York City.

So, I thought I would check the data. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment in the hardware store category (which is distinct from “home centers,” presumably stores like Lowes and Home Depot) increased from 143,600 in September of 2009 to 159,400 in September, 2019. This is an increase of 11.0 percent. That is somewhat less than the 16.6 percent overall job growth over this period, but hardly makes it appear like hardware stores are dying.

Long and short, it looks like the factors that led to the closing of the hardware store Wu patronizes are largely unique to New York City and don’t reflect the picture throughout the country.

I have a lot of respect for Tim Wu, who has done much valuable work on concentration in the tech sector. However, when I saw his NYT piece on the death of the local hardware store I was somewhat skeptical. Most immediately, my experience with my thriving local hardware store (which gives great service, if any readers make it to Kanab) is 180 degrees at odds with his experience with his local hardware story in New York City.

So, I thought I would check the data. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, employment in the hardware store category (which is distinct from “home centers,” presumably stores like Lowes and Home Depot) increased from 143,600 in September of 2009 to 159,400 in September, 2019. This is an increase of 11.0 percent. That is somewhat less than the 16.6 percent overall job growth over this period, but hardly makes it appear like hardware stores are dying.

Long and short, it looks like the factors that led to the closing of the hardware store Wu patronizes are largely unique to New York City and don’t reflect the picture throughout the country.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This was in the context of the tariffs he has imposed on imports from China. According to the Washington Post, Trump boasted:

“I like what’s happening right now. We’re taking in billions and billions of dollars.”

Tariffs, of course, are taxes on imports. The evidence is overwhelming that the vast majority of these taxes are being borne either by consumers or retailers in the United States. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the price of imports from China has fallen just 1.6 percent over the last year. This means that people in the United States are paying the overwhelming majority of the tariffs that run as high as 25 percent and apparently Donald Trump is very happy about that.

This was in the context of the tariffs he has imposed on imports from China. According to the Washington Post, Trump boasted:

“I like what’s happening right now. We’re taking in billions and billions of dollars.”

Tariffs, of course, are taxes on imports. The evidence is overwhelming that the vast majority of these taxes are being borne either by consumers or retailers in the United States. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the price of imports from China has fallen just 1.6 percent over the last year. This means that people in the United States are paying the overwhelming majority of the tariffs that run as high as 25 percent and apparently Donald Trump is very happy about that.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión