Those wondering why the Obama administration has not been more aggressive in pushing for stimulus got their answer today in a Washington Post article on the selection of Representative Paul Ryan as Mitt Romney’s running mate. The article includes a statement by Jim Messina, the head of President Obama’s re-election campaign:

Messina attacked Ryan by saying:

“As a member of Congress, Ryan rubber-stamped the reckless Bush economic policies that exploded our deficit and crashed our economy. Now the Romney-Ryan ticket would take us back by repeating the same, catastrophic mistakes.”

Actually, the economic policies that “exploded our deficit” helped the economy to grow. The deficit had come to down to sustainable levels by 2007. The economy crashed in 2008 because the housing bubble, which had been left to grow unchecked, collapsed and brought the economy down with it. While Bush, along with the Greenspan-Bernanke Fed, can be blamed for ignoring the growth of the housing bubble, it is blatantly absurd to blame the economic collapse on the deficit.

Presumably Messina has some knowledge of this recent economic history. That means that he is fabricating a story to attack his political opponent. Alternatively, he is completely clueless about the economy and President Obama has given his top campaign position to a person astoundingly ignorant about the economy. Either way, the Post should have corrected Messina’s statement for readers who may have been misled.

Those wondering why the Obama administration has not been more aggressive in pushing for stimulus got their answer today in a Washington Post article on the selection of Representative Paul Ryan as Mitt Romney’s running mate. The article includes a statement by Jim Messina, the head of President Obama’s re-election campaign:

Messina attacked Ryan by saying:

“As a member of Congress, Ryan rubber-stamped the reckless Bush economic policies that exploded our deficit and crashed our economy. Now the Romney-Ryan ticket would take us back by repeating the same, catastrophic mistakes.”

Actually, the economic policies that “exploded our deficit” helped the economy to grow. The deficit had come to down to sustainable levels by 2007. The economy crashed in 2008 because the housing bubble, which had been left to grow unchecked, collapsed and brought the economy down with it. While Bush, along with the Greenspan-Bernanke Fed, can be blamed for ignoring the growth of the housing bubble, it is blatantly absurd to blame the economic collapse on the deficit.

Presumably Messina has some knowledge of this recent economic history. That means that he is fabricating a story to attack his political opponent. Alternatively, he is completely clueless about the economy and President Obama has given his top campaign position to a person astoundingly ignorant about the economy. Either way, the Post should have corrected Messina’s statement for readers who may have been misled.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

There have been numerous stories about how workers don’t have the necessary skills for the available jobs. There is little evidence of this in the data. Wages are not rising rapidly in any major occupational grouping. If employers could not find workers with the necessary skills then they should be raising wages to pull away the limited group of qualified workers from competitors, unless of course the employers were too incompetent to understand that higher wages are necessary to attract workers.

Anyhow, Yahoo clearly has trouble attracting staff with the necessary skills in arithmetic and logic, since it ran a piece on Social Security which contained major errors in one or both. The piece recounts the story of Mary Ann Sorrentino, a woman who spent a career in relatively low-paying jobs, but nonetheless managed to save and invest successfully and thereby accumulate a substantial amount to support her retirement.

It then tells readers:

“Now nearly 70, Sorrentino says her mother’s admonitions saved her — especially considering that Social Security, that very American of safety nets, hasn’t quite panned out the way many had hoped. She dubs them the “reality-challenged,” referring to those who have long paid into the Social Security kitty with a blind belief they’ll see their investments, and perhaps more, kindly returned to them by the federal government.

That dream has soured, says an Associated Press study this week. The average American who retires now will receive less Social Security money than what he contributed over a working life. There are variables (retirement age and income level are two big ones), but for many, it’s clear: Social Security, she ain’t what she used to be.”

Just about every assertion in this piece is wrong. In fact, the statements are sufficiently inaccurate to be libelous. If Yahoo had mischaracterized a private corporation like Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley the same way, it is likely that it would be facing a serious lawsuit.

In fact, the study cited by Associated Press (Associated Press did not do a study) did not indicate that Social Security is paying out less than planned. The last cut in benefits was put into law 29 years. This means that if workers had looked at benefits they had been promised at any date since those cuts, they would be seeing exactly the benefits that they expected. The only “reality-challenged” folks in this story are those at Yahoo who apparently did not know this fact.

Also, the study showed that most workers would in fact get more than the standard return on the money they put into Social Security. It is only the top quarter or so of wage earners who could expect to get somewhat less than a normal return on the money they invested in Social Security. (Yahoo’s concern for these relatively well off workers is ironic, since the Bowles-Simpson plan, which is enthusiastically supported by most of the Washington establishment, calls for further cuts to these workers’ benefits.)

The Yahoo piece also badly misleads readers about the financial condition of Social Security. It told readers of a small business owner who doesn’t expect to retire until 2039:

“and that Social Security, according to the Congressional Budget Office, could be bone-dry by 2040.”

Actually the Congressional Budget Office does not say that Social Security could be bone-dry by 2040. Its projections show that it will only have enough revenue at that point to pay about 80 percent of scheduled benefits. However, the payable benefit projected for 2040 would still be larger than the average benefit that retirees receive today.

That would be the case if Congress never took any steps to address the projected shortfall. The additional funding needed to pay the full scheduled benefit would be roughly equal to half of the cost of the war in Iraq at its peak. It is likely that a voting population that has a substantially higher share of retirees than we do at present would insist that Congress find the funding to maintain full scheduled benefits.

Yahoo has been having serious management and financial problems in recent years. If this article is typical of its reporting it is a virtual certainty that the company will be out of business long before Social Security faces any real financial problems.

There have been numerous stories about how workers don’t have the necessary skills for the available jobs. There is little evidence of this in the data. Wages are not rising rapidly in any major occupational grouping. If employers could not find workers with the necessary skills then they should be raising wages to pull away the limited group of qualified workers from competitors, unless of course the employers were too incompetent to understand that higher wages are necessary to attract workers.

Anyhow, Yahoo clearly has trouble attracting staff with the necessary skills in arithmetic and logic, since it ran a piece on Social Security which contained major errors in one or both. The piece recounts the story of Mary Ann Sorrentino, a woman who spent a career in relatively low-paying jobs, but nonetheless managed to save and invest successfully and thereby accumulate a substantial amount to support her retirement.

It then tells readers:

“Now nearly 70, Sorrentino says her mother’s admonitions saved her — especially considering that Social Security, that very American of safety nets, hasn’t quite panned out the way many had hoped. She dubs them the “reality-challenged,” referring to those who have long paid into the Social Security kitty with a blind belief they’ll see their investments, and perhaps more, kindly returned to them by the federal government.

That dream has soured, says an Associated Press study this week. The average American who retires now will receive less Social Security money than what he contributed over a working life. There are variables (retirement age and income level are two big ones), but for many, it’s clear: Social Security, she ain’t what she used to be.”

Just about every assertion in this piece is wrong. In fact, the statements are sufficiently inaccurate to be libelous. If Yahoo had mischaracterized a private corporation like Goldman Sachs or Morgan Stanley the same way, it is likely that it would be facing a serious lawsuit.

In fact, the study cited by Associated Press (Associated Press did not do a study) did not indicate that Social Security is paying out less than planned. The last cut in benefits was put into law 29 years. This means that if workers had looked at benefits they had been promised at any date since those cuts, they would be seeing exactly the benefits that they expected. The only “reality-challenged” folks in this story are those at Yahoo who apparently did not know this fact.

Also, the study showed that most workers would in fact get more than the standard return on the money they put into Social Security. It is only the top quarter or so of wage earners who could expect to get somewhat less than a normal return on the money they invested in Social Security. (Yahoo’s concern for these relatively well off workers is ironic, since the Bowles-Simpson plan, which is enthusiastically supported by most of the Washington establishment, calls for further cuts to these workers’ benefits.)

The Yahoo piece also badly misleads readers about the financial condition of Social Security. It told readers of a small business owner who doesn’t expect to retire until 2039:

“and that Social Security, according to the Congressional Budget Office, could be bone-dry by 2040.”

Actually the Congressional Budget Office does not say that Social Security could be bone-dry by 2040. Its projections show that it will only have enough revenue at that point to pay about 80 percent of scheduled benefits. However, the payable benefit projected for 2040 would still be larger than the average benefit that retirees receive today.

That would be the case if Congress never took any steps to address the projected shortfall. The additional funding needed to pay the full scheduled benefit would be roughly equal to half of the cost of the war in Iraq at its peak. It is likely that a voting population that has a substantially higher share of retirees than we do at present would insist that Congress find the funding to maintain full scheduled benefits.

Yahoo has been having serious management and financial problems in recent years. If this article is typical of its reporting it is a virtual certainty that the company will be out of business long before Social Security faces any real financial problems.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT has an article on how companies in the developing world have increased production of coolants that contribute to global warming in order to get credits for destroying them. This is the outcome of some of the perverse incentives created by the Clean Development Mechanism in the Kyoto agreement.

This sort of gaming was predictable and predicted at the time. The basic problem was that there was no well-developed baseline against which to assign credits to ensure that money was only paid in situations where it actually led to emissions reductions.

The article included a comment from David Doniger, a member of the “who could have known crowd” who is cited as an expert:

“‘I was a climate negotiator, and no one had this in mind,’ said David Doniger of the Natural Resources Defense Council. ‘It turns out you get nearly 100 times more from credits than it costs to do it. It turned the economics of the business on its head.'”

It would have been worth mentioning that Doniger is wrong, people did have this in mind. It was just the case that the people in positions of authority, and who were cited as experts on the topic, apparently did not understand that this sort of gaming would inevitably result from the deal they crafted.

The NYT has an article on how companies in the developing world have increased production of coolants that contribute to global warming in order to get credits for destroying them. This is the outcome of some of the perverse incentives created by the Clean Development Mechanism in the Kyoto agreement.

This sort of gaming was predictable and predicted at the time. The basic problem was that there was no well-developed baseline against which to assign credits to ensure that money was only paid in situations where it actually led to emissions reductions.

The article included a comment from David Doniger, a member of the “who could have known crowd” who is cited as an expert:

“‘I was a climate negotiator, and no one had this in mind,’ said David Doniger of the Natural Resources Defense Council. ‘It turns out you get nearly 100 times more from credits than it costs to do it. It turned the economics of the business on its head.'”

It would have been worth mentioning that Doniger is wrong, people did have this in mind. It was just the case that the people in positions of authority, and who were cited as experts on the topic, apparently did not understand that this sort of gaming would inevitably result from the deal they crafted.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT article noted new evidence of economic weakness in Germany and Italy then told readers:

“flagging growth is complicating European leaders’ quest to restore confidence in the euro zone.”

Of course one of the main reasons that growth in Europe is weak is the austerity measures that have been imposed across Europe. The loss of demand from the government means that there is less demand in the economy and therefore less growth. Apparently those in leadership positions believe that the confidence fairy will make up for the loss demand from the public sector, but unfortunate for workers living in Europe, the confidence fairy does not exist.

A NYT article noted new evidence of economic weakness in Germany and Italy then told readers:

“flagging growth is complicating European leaders’ quest to restore confidence in the euro zone.”

Of course one of the main reasons that growth in Europe is weak is the austerity measures that have been imposed across Europe. The loss of demand from the government means that there is less demand in the economy and therefore less growth. Apparently those in leadership positions believe that the confidence fairy will make up for the loss demand from the public sector, but unfortunate for workers living in Europe, the confidence fairy does not exist.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

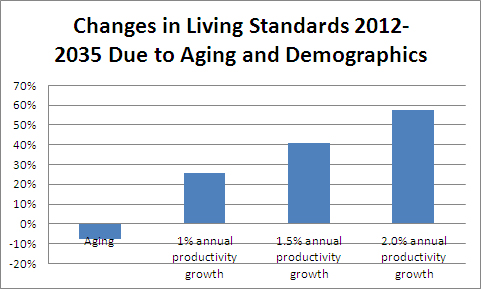

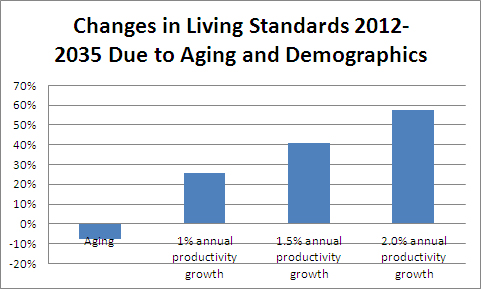

Ding, ding, ding! Robert Samuelson has just written the 1 millionth piece to appear in the Washington Post claiming that an aging population will undermine our children’s prosperity. He gets awarded a miniature golden baseball bat to symbolize his and the newspapers decades of bashing the elderly and trying to take away their Social Security and Medicare.

Arithmetic fans know that if our children and grandchildren live worse than we do it will be because the folks at the top grabbed away all the money. In any plausible scenario the gains from productivity growth will swamp any additional burdens placed on workers from a larger population of retirees.

The projections that Samuelson cites to make his point in fact demonstrate the opposite. He told readers:

“The ratio of workers to retirees, 5-to-1 in 1960 and 3-to-1 in 2010, is projected at nearly 2-to-1 by 2025.”

Yep, we have had a sharp decline in the ratio of workers to retirees from 1960 to 2010 (most of it by 1990) and yet average living standards rose substantially. This means that there is no reason that average living standards won’t continue to rise in the next several decades as the ratio of workers to retirees falls further.

The simple chart below compares the impact of the projected change in the ratio of workers to retirees on the living standards of workers assuming that an average retiree has 75 percent of the living standard of an average worker. It compares scenarios of 1.0 percent, 1.5 percent and 2.0 percent productivity growth.

Source: Author’s calculation, see text.

As can be seen, the impact of higher productivity growth in raising living standards swamps the impact of demographic change in lowering living standards. It is also important to note that the negative demographic shift ends in 2035. After that point the demographics stabilize or even improve slightly, which means that all future gains in productivity will go into the pockets of our children and grandchildren.

Of course BTP fans everywhere are jumping and down yelling that ordinary workers have not been seeing the gains of productivity growth. Real wages have been nearly stagnant for the last three decades. This is of course right, but that is exactly the point.

If our children and grandchildren do not enjoy substantially higher living standards than we do today, it will not be because they are paying for their parents or grandparents’ Social Security. It will be because the one percent have rigged the economic system so that most of the gains from growth go to the top.

The answer here is not cutting Social Security and Medicare, it is ending too big to fail insurance for huge banks and otherwise cutting a bloated financial system down to size. It is about ending trade and monetary policies that are decided to benefit the rich at the expense of the rest of us. It is about curtailing patent monopolies that has us spending $300 billion a year on drugs that would sell for $30 billion in a competitive market. And it is about fixing a corporate governance system where boards of directors are given 6-figure payoffs to look the other way as top management pillages the company. (See The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.)

In other words, the real story is not about inter-generational equality, no matter how many times the Post repeats this line. The real story is about intra-generational inequality.

Ding, ding, ding! Robert Samuelson has just written the 1 millionth piece to appear in the Washington Post claiming that an aging population will undermine our children’s prosperity. He gets awarded a miniature golden baseball bat to symbolize his and the newspapers decades of bashing the elderly and trying to take away their Social Security and Medicare.

Arithmetic fans know that if our children and grandchildren live worse than we do it will be because the folks at the top grabbed away all the money. In any plausible scenario the gains from productivity growth will swamp any additional burdens placed on workers from a larger population of retirees.

The projections that Samuelson cites to make his point in fact demonstrate the opposite. He told readers:

“The ratio of workers to retirees, 5-to-1 in 1960 and 3-to-1 in 2010, is projected at nearly 2-to-1 by 2025.”

Yep, we have had a sharp decline in the ratio of workers to retirees from 1960 to 2010 (most of it by 1990) and yet average living standards rose substantially. This means that there is no reason that average living standards won’t continue to rise in the next several decades as the ratio of workers to retirees falls further.

The simple chart below compares the impact of the projected change in the ratio of workers to retirees on the living standards of workers assuming that an average retiree has 75 percent of the living standard of an average worker. It compares scenarios of 1.0 percent, 1.5 percent and 2.0 percent productivity growth.

Source: Author’s calculation, see text.

As can be seen, the impact of higher productivity growth in raising living standards swamps the impact of demographic change in lowering living standards. It is also important to note that the negative demographic shift ends in 2035. After that point the demographics stabilize or even improve slightly, which means that all future gains in productivity will go into the pockets of our children and grandchildren.

Of course BTP fans everywhere are jumping and down yelling that ordinary workers have not been seeing the gains of productivity growth. Real wages have been nearly stagnant for the last three decades. This is of course right, but that is exactly the point.

If our children and grandchildren do not enjoy substantially higher living standards than we do today, it will not be because they are paying for their parents or grandparents’ Social Security. It will be because the one percent have rigged the economic system so that most of the gains from growth go to the top.

The answer here is not cutting Social Security and Medicare, it is ending too big to fail insurance for huge banks and otherwise cutting a bloated financial system down to size. It is about ending trade and monetary policies that are decided to benefit the rich at the expense of the rest of us. It is about curtailing patent monopolies that has us spending $300 billion a year on drugs that would sell for $30 billion in a competitive market. And it is about fixing a corporate governance system where boards of directors are given 6-figure payoffs to look the other way as top management pillages the company. (See The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive.)

In other words, the real story is not about inter-generational equality, no matter how many times the Post repeats this line. The real story is about intra-generational inequality.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

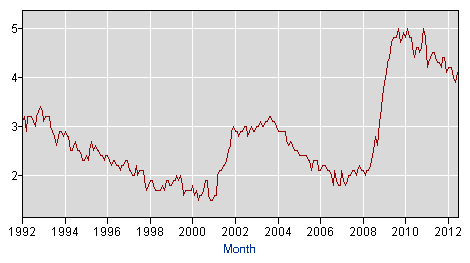

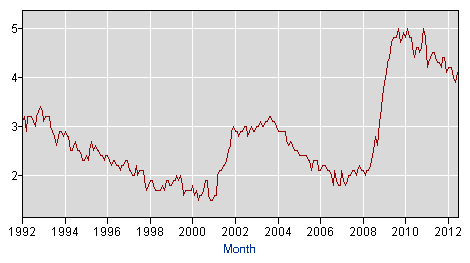

Jeffrey Sachs has played a useful role in challenging the economic orthodoxy in many areas over the last three years. However, when he tries to tell us that the current downturn is structural not cyclical he is way over his head in the quicksand of the orthodoxy.

Let’s start with his simple bold assertion:

“Consider the new U.S. unemployment announcement. If you are a college graduate, there is no employment crisis. 72.7 percent of the college-educated population age-25 and over is working. The unemployment rate is 4.1 percent. Incomes are good.”

Umm, no, that’s not right. If we go back to 2007 we would see that the unemployment rate for college grads was 1.9 percent at its low that year, less than half of the current rate. It averaged 1.6 percent in 2000.

Unemployment Rate for College Grads, 25 years and Over

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

If the current unemployment in the U.S. economy were structural than we should expect to see lower than normal for these college grads whose labor is in short supply. Instead, we see that their unemployment rate is more than twice the pre-recession level and close two and half times its 2000 level.

We should also expect to see that real wages for college grads are rising rapidly. They aren’t. They have not even kept pace with inflation for the last dozen years.

In short, Sachs does not even have the beginning of an argument here. He’d better find some new data or give up his argument that the causes of unemployment are structural. His data indicate the opposite.

Jeffrey Sachs has played a useful role in challenging the economic orthodoxy in many areas over the last three years. However, when he tries to tell us that the current downturn is structural not cyclical he is way over his head in the quicksand of the orthodoxy.

Let’s start with his simple bold assertion:

“Consider the new U.S. unemployment announcement. If you are a college graduate, there is no employment crisis. 72.7 percent of the college-educated population age-25 and over is working. The unemployment rate is 4.1 percent. Incomes are good.”

Umm, no, that’s not right. If we go back to 2007 we would see that the unemployment rate for college grads was 1.9 percent at its low that year, less than half of the current rate. It averaged 1.6 percent in 2000.

Unemployment Rate for College Grads, 25 years and Over

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

If the current unemployment in the U.S. economy were structural than we should expect to see lower than normal for these college grads whose labor is in short supply. Instead, we see that their unemployment rate is more than twice the pre-recession level and close two and half times its 2000 level.

We should also expect to see that real wages for college grads are rising rapidly. They aren’t. They have not even kept pace with inflation for the last dozen years.

In short, Sachs does not even have the beginning of an argument here. He’d better find some new data or give up his argument that the causes of unemployment are structural. His data indicate the opposite.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT ran a lengthy story on the possibilities of manufacturing electronics in the United States. Near the end of the piece it discusses divisions in the Obama administration on measures to try to bring more manufacturing back to the United States.

On the one hand, it notes the view of Ron Bloom, who had been the president’s senior advisor on manufacturing policy, that the U.S. should take steps to push down the value of the dollar in order to make manufacturing in the United States more competitive. It then contrasts this view with that of Lawrence H. Summers, formerly the top economic adviser to Obama. The piece tells readers:

“along with many economists, Mr. Summers argued that an overly aggressive trade stance could hurt manufacturing — by, for instance, pushing up the price of imported steel used by carmakers — and over time, drive companies away. “

Actually, standard economic theory would argue that a lower valued dollar is exactly the mechanism through which the trade deficit should be brought down. In a system of floating exchange rates, the excess supply of currency on world markets from a deficit country like the United States is supposed to bring down the value of its currency. This makes its goods more competitive in world markets, reducing the size of its trade deficit.

The expected drop in the value of the currency is not taking place today with the dollar because a number of countries are buying up large amounts of dollars in order to prop up its value against their own currencies. By keeping the dollar over-valued they are able to sustain their trade surpluses with the United States.

It is worth noting that by definition, if the United States has a large trade deficit then the country has large negative national savings. This means that by supporting a policy that leads to a large trade deficit, Summers was arguing for either large budget deficits and/or large negative private savings, as we saw at the peak of the housing bubble. Perhaps Mr. Summers does not understand the implications of his position, but there is no logical way around it.

It is also worth noting that the over-valued dollar policy supported by Summers acts to redistribute income from workers who are exposed to international competition, like manufacturing workers, to workers who are largely protected from international competition, like doctors, lawyers and other highly educated professionals. In other words, it can be seen as one of the policies that redistributes money from the 99 percent to the one percent.

The NYT ran a lengthy story on the possibilities of manufacturing electronics in the United States. Near the end of the piece it discusses divisions in the Obama administration on measures to try to bring more manufacturing back to the United States.

On the one hand, it notes the view of Ron Bloom, who had been the president’s senior advisor on manufacturing policy, that the U.S. should take steps to push down the value of the dollar in order to make manufacturing in the United States more competitive. It then contrasts this view with that of Lawrence H. Summers, formerly the top economic adviser to Obama. The piece tells readers:

“along with many economists, Mr. Summers argued that an overly aggressive trade stance could hurt manufacturing — by, for instance, pushing up the price of imported steel used by carmakers — and over time, drive companies away. “

Actually, standard economic theory would argue that a lower valued dollar is exactly the mechanism through which the trade deficit should be brought down. In a system of floating exchange rates, the excess supply of currency on world markets from a deficit country like the United States is supposed to bring down the value of its currency. This makes its goods more competitive in world markets, reducing the size of its trade deficit.

The expected drop in the value of the currency is not taking place today with the dollar because a number of countries are buying up large amounts of dollars in order to prop up its value against their own currencies. By keeping the dollar over-valued they are able to sustain their trade surpluses with the United States.

It is worth noting that by definition, if the United States has a large trade deficit then the country has large negative national savings. This means that by supporting a policy that leads to a large trade deficit, Summers was arguing for either large budget deficits and/or large negative private savings, as we saw at the peak of the housing bubble. Perhaps Mr. Summers does not understand the implications of his position, but there is no logical way around it.

It is also worth noting that the over-valued dollar policy supported by Summers acts to redistribute income from workers who are exposed to international competition, like manufacturing workers, to workers who are largely protected from international competition, like doctors, lawyers and other highly educated professionals. In other words, it can be seen as one of the policies that redistributes money from the 99 percent to the one percent.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Catherine Rampell had an interesting discussion of the Fed’s likely course of action at its September meeting based on the July numbers. While the piece acknowledged the July jobs number from the establishment survey was somewhat better than expected, it concludes that the Fed is likely to move based on the weakness of the data from the household survey.

I’d have to disagree with that assessment. The household survey is far more erratic than the establishment survey. For example, it shows a jump of 422,000 jobs in May. Anyone remember that boom? Last June it reported a drop of 423,000. In August and September the household survey showed a combined gain of 657,000 jobs at a time when many news accounts were debating the likelihood of a double-dip recession.

It is easy to go back and find large one or even two month jumps or plunges in employment in the household survey that correspond to nothing that can be identified in the economy at the time. The Fed is surely aware of the household survey’s erratic pattern.

This means that when they sit down at their September meeting, the major news they will be considering on the labor market front will be the establishment survey. While the July data should warrant stronger steps to boost the economy (it will take 160 months of job growth at this pace to restore full employment), since they were not prepared to move before the July report, it is unlikely that a better than expected jobs number will prompt action.

Of course they will also have the August numbers by then.

Catherine Rampell had an interesting discussion of the Fed’s likely course of action at its September meeting based on the July numbers. While the piece acknowledged the July jobs number from the establishment survey was somewhat better than expected, it concludes that the Fed is likely to move based on the weakness of the data from the household survey.

I’d have to disagree with that assessment. The household survey is far more erratic than the establishment survey. For example, it shows a jump of 422,000 jobs in May. Anyone remember that boom? Last June it reported a drop of 423,000. In August and September the household survey showed a combined gain of 657,000 jobs at a time when many news accounts were debating the likelihood of a double-dip recession.

It is easy to go back and find large one or even two month jumps or plunges in employment in the household survey that correspond to nothing that can be identified in the economy at the time. The Fed is surely aware of the household survey’s erratic pattern.

This means that when they sit down at their September meeting, the major news they will be considering on the labor market front will be the establishment survey. While the July data should warrant stronger steps to boost the economy (it will take 160 months of job growth at this pace to restore full employment), since they were not prepared to move before the July report, it is unlikely that a better than expected jobs number will prompt action.

Of course they will also have the August numbers by then.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A piece that noted the slow pace of the recovery and compared it to other recessions never once mentioned the housing bubble. The fact that this recession was brought on by the collapse of a housing bubble, as opposed to the Fed raising interest rates to slow the economy, makes it qualitatively different from prior post-war recessions with the exception of the 2001 downturn that was brought on by the collapse of the stock bubble. It would have been worth making this point instead of turning the discussion into a he said/she said that concludes:

“‘The debate is unresolvable,’ said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the American Action Forum, a center-right think tank, and the former director of the Congressional Budget Office. ‘We don’t have a lot of data points. We only have about a dozen recessions where we have a lot of data.'”

A piece that noted the slow pace of the recovery and compared it to other recessions never once mentioned the housing bubble. The fact that this recession was brought on by the collapse of a housing bubble, as opposed to the Fed raising interest rates to slow the economy, makes it qualitatively different from prior post-war recessions with the exception of the 2001 downturn that was brought on by the collapse of the stock bubble. It would have been worth making this point instead of turning the discussion into a he said/she said that concludes:

“‘The debate is unresolvable,’ said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, president of the American Action Forum, a center-right think tank, and the former director of the Congressional Budget Office. ‘We don’t have a lot of data points. We only have about a dozen recessions where we have a lot of data.'”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión