A Morning Edition segment on the Fed’s likely actions included a comment from Karen Dynan, the co-director of economic studies at the Brookings Institution saying:

“our housing market remains in very poor shape. It may have turned the corner, but conditions still look pretty bleak.”

Actually house prices are pretty much back on their long-term trend path. The current sales rate is also at or above its trend level. It is true that house prices are still well below their bubble peaks, but that should be expected. It would be unreasonable to expect the Nasdaq to return to the prices it reached at the peak of the stock bubble. Similarly, there is no reason to expect (or want) house prices to return to their bubble peak.

A Morning Edition segment on the Fed’s likely actions included a comment from Karen Dynan, the co-director of economic studies at the Brookings Institution saying:

“our housing market remains in very poor shape. It may have turned the corner, but conditions still look pretty bleak.”

Actually house prices are pretty much back on their long-term trend path. The current sales rate is also at or above its trend level. It is true that house prices are still well below their bubble peaks, but that should be expected. It would be unreasonable to expect the Nasdaq to return to the prices it reached at the peak of the stock bubble. Similarly, there is no reason to expect (or want) house prices to return to their bubble peak.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT article reports that one of the background issues in the strike of Chicago public school teachers is the increased use of charter schools, which is advocated by Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel. It would have been worth reminding readers that charter schools do not on average outperform the public schools they replace. If Emanuel is advocating increased use of charter schools he is either unfamiliar with recent research in education or has some motive other than improving student performance.

A NYT article reports that one of the background issues in the strike of Chicago public school teachers is the increased use of charter schools, which is advocated by Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel. It would have been worth reminding readers that charter schools do not on average outperform the public schools they replace. If Emanuel is advocating increased use of charter schools he is either unfamiliar with recent research in education or has some motive other than improving student performance.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In his column today George Will notes the Fed’s responsibility to maintain price stability and high employment and tells readers:

“Achieving the former is the best thing the Fed can do for the latter.”

Apparently Will has not been following what has happened in the economy recently. While inflation has remained low and relatively stable, unemployment has soared. He also apparently does not recognize how the Fed hopes to boost economic growth through quantitative easing.

The biggest impact from lower interest rates is probably from mortgage refinancing. This both directly generates economic activity through people employed in the process (e.g. banking staff, appraisers etc.) and indirectly by reducing payments and freeing up money for other consumption.

The second biggest impact is on lowering the value of the dollar relative to other currencies, which will reduce the trade deficit. Anyone who does not want a large budget deficit and/or negative private savings (like we had at the peak of the housing bubble) must want to see the trade deficit move closer to balance. This is an accounting identity — there is no way around it. And, there is no plausible mechanism to get the trade deficit closer to balance except by reducing the value of the dollar.

For some reason Will fails to mention either the impact of quantitative easing on mortgage refinancing or the impact on the trade deficit. There is also zero evidence of the hyper-inflation that he and other opponents of more aggressive Fed actions have been warning about for years.

In his column today George Will notes the Fed’s responsibility to maintain price stability and high employment and tells readers:

“Achieving the former is the best thing the Fed can do for the latter.”

Apparently Will has not been following what has happened in the economy recently. While inflation has remained low and relatively stable, unemployment has soared. He also apparently does not recognize how the Fed hopes to boost economic growth through quantitative easing.

The biggest impact from lower interest rates is probably from mortgage refinancing. This both directly generates economic activity through people employed in the process (e.g. banking staff, appraisers etc.) and indirectly by reducing payments and freeing up money for other consumption.

The second biggest impact is on lowering the value of the dollar relative to other currencies, which will reduce the trade deficit. Anyone who does not want a large budget deficit and/or negative private savings (like we had at the peak of the housing bubble) must want to see the trade deficit move closer to balance. This is an accounting identity — there is no way around it. And, there is no plausible mechanism to get the trade deficit closer to balance except by reducing the value of the dollar.

For some reason Will fails to mention either the impact of quantitative easing on mortgage refinancing or the impact on the trade deficit. There is also zero evidence of the hyper-inflation that he and other opponents of more aggressive Fed actions have been warning about for years.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I’ve heard many folks complain that Chicago’s teachers are only concerned about their wages and benefits and not over the education received by the children. As my friend Larry Mishel reminds me, there is an important reason that the teachers’ union is only talking about wages and benefits in the context of the strike: it’s the law.

These are mandatory topics for negotiation under U.S. labor law. Issues about how the schools are run fall under management prerogatives. While the union and management are free to discuss these issues, the union cannot legally strike over them. Therefore if the union were to explicitly put forward conditions that directly related to the quality of education as a reason for the strike, the city could pursue legal action against the union and its officers for conducting an illegal strike.

It would be appropriate for reporters to point out this fact in discussing the strike. Those unhappy that the union is not making demands on behalf of students should be complaining about labor law, not the teachers’ union.

Those interested in how Chicago’s teachers envision ways to improve the quality of education might look at this pamphlet they published earlier this year, as cited in a blogpost by Dylan Matthews. Matthews acknowledges that the measures listed are backed up by research showing their effectiveness, but notes that the plan comes with a $713 million price tag.

That’s not trivial, but if we assume that Chicago’s per capita GDP is equal to the national average, then it amounts to less than 0.5 percent of its annual income. The union also proposed ways to raise the money, all of which focus on getting more money from the wealthy.

My personal favorite is a tax on financial transactions. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange is the largest exchange for commodities and futures trading in the country. The union proposed a tax of 6 cents per transactions, which they calculate would raise about $110 million a year.

Matthews seems to view this tax as impractical suggesting that trading would just move to New York. He cites the example of a tax on stock trades in Sweden which led trading volume to quickly migrate to London.

This is an especially inappropriate example. The tax in Sweden was large (1.0 percent of the value of the trade) and almost seems to have been designed to be evaded. Brokerage houses could open up shops in Sweden for trades done in the U.K.. It is a bit more difficult to imagine all of Chicago’s traders shutting down over a tax of 6 cents per transactions.

This is not the way I would impose the tax (I would take it as a percent of the trade), but based on past calculations, this tax rate would correspond to roughly one hundredth of a basis point (0.0001 percent) of the nominal value of trades. It’s hard to envision the Chicago market shutting down over a tax of this magnitude.

As with the other tax proposals, Matthews is quite right that there will be enormous political obstacles. But if we have a plan on the table that we have good reason to believe will improve the education of our children, and the people with money and power in Chicago don’t want to foot the tab, why are we blaming the teachers for the poor educational outcomes?

I’ve heard many folks complain that Chicago’s teachers are only concerned about their wages and benefits and not over the education received by the children. As my friend Larry Mishel reminds me, there is an important reason that the teachers’ union is only talking about wages and benefits in the context of the strike: it’s the law.

These are mandatory topics for negotiation under U.S. labor law. Issues about how the schools are run fall under management prerogatives. While the union and management are free to discuss these issues, the union cannot legally strike over them. Therefore if the union were to explicitly put forward conditions that directly related to the quality of education as a reason for the strike, the city could pursue legal action against the union and its officers for conducting an illegal strike.

It would be appropriate for reporters to point out this fact in discussing the strike. Those unhappy that the union is not making demands on behalf of students should be complaining about labor law, not the teachers’ union.

Those interested in how Chicago’s teachers envision ways to improve the quality of education might look at this pamphlet they published earlier this year, as cited in a blogpost by Dylan Matthews. Matthews acknowledges that the measures listed are backed up by research showing their effectiveness, but notes that the plan comes with a $713 million price tag.

That’s not trivial, but if we assume that Chicago’s per capita GDP is equal to the national average, then it amounts to less than 0.5 percent of its annual income. The union also proposed ways to raise the money, all of which focus on getting more money from the wealthy.

My personal favorite is a tax on financial transactions. The Chicago Mercantile Exchange is the largest exchange for commodities and futures trading in the country. The union proposed a tax of 6 cents per transactions, which they calculate would raise about $110 million a year.

Matthews seems to view this tax as impractical suggesting that trading would just move to New York. He cites the example of a tax on stock trades in Sweden which led trading volume to quickly migrate to London.

This is an especially inappropriate example. The tax in Sweden was large (1.0 percent of the value of the trade) and almost seems to have been designed to be evaded. Brokerage houses could open up shops in Sweden for trades done in the U.K.. It is a bit more difficult to imagine all of Chicago’s traders shutting down over a tax of 6 cents per transactions.

This is not the way I would impose the tax (I would take it as a percent of the trade), but based on past calculations, this tax rate would correspond to roughly one hundredth of a basis point (0.0001 percent) of the nominal value of trades. It’s hard to envision the Chicago market shutting down over a tax of this magnitude.

As with the other tax proposals, Matthews is quite right that there will be enormous political obstacles. But if we have a plan on the table that we have good reason to believe will improve the education of our children, and the people with money and power in Chicago don’t want to foot the tab, why are we blaming the teachers for the poor educational outcomes?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

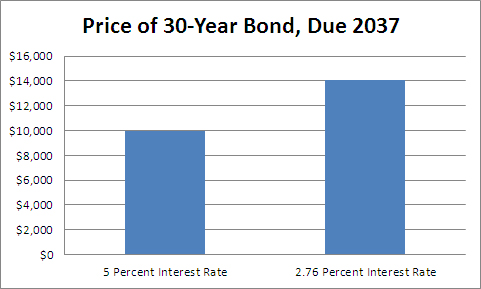

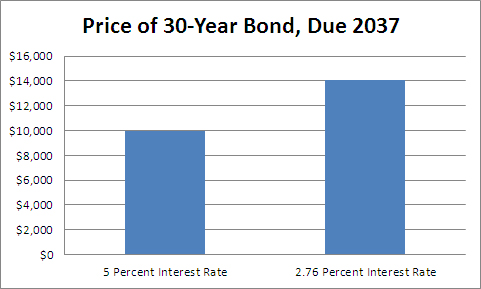

As the Fed has attempted to push interest rates down with the purpose of boosting the economy, there have been numerous stories mourning the situation of savers who see little return on their money. The NYT gave us such a piece on Tuesday.

While those who have all their savings in short-term assets like savings accounts and money market funds are seeing low returns, the low return story does not apply to all savers. Of course those who have money in the stock market have done quite well, with prices nearly double their lows from 2009.

However, even people who do not have money in the stock market would have done well if they had put money in long-term bonds. The graph below shows the price of a 30-year bond that comes due in 2037, assuming that it was bought in 2007 with a 5 percent yield (roughly the interest rate at the time).

Source: Smart Money Bond Calculator.

The bond that our troubled saver purchased in 2007 for $10,000 would be worth a bit more than $14,000 in today’s low interest rate environment. That isn’t exactly the sort of situation that would normally call for violin music.

As a practical matter, there are people who are losing in this story, but realistically there are not a lot of people who both have substantial savings (enough that the interest makes up a big share of their income) and who kept it exclusively in short-term assets.

There are no policies to increase growth that leave no one harmed. (If you think you know of one, then you haven’t thought through the implications of the policy carefully enough.) The winners from a policy to boost growth through lower interest rates vastly outnumber the losers. The biggest grounds for complaint is that the Fed did not go far enough.

As the Fed has attempted to push interest rates down with the purpose of boosting the economy, there have been numerous stories mourning the situation of savers who see little return on their money. The NYT gave us such a piece on Tuesday.

While those who have all their savings in short-term assets like savings accounts and money market funds are seeing low returns, the low return story does not apply to all savers. Of course those who have money in the stock market have done quite well, with prices nearly double their lows from 2009.

However, even people who do not have money in the stock market would have done well if they had put money in long-term bonds. The graph below shows the price of a 30-year bond that comes due in 2037, assuming that it was bought in 2007 with a 5 percent yield (roughly the interest rate at the time).

Source: Smart Money Bond Calculator.

The bond that our troubled saver purchased in 2007 for $10,000 would be worth a bit more than $14,000 in today’s low interest rate environment. That isn’t exactly the sort of situation that would normally call for violin music.

As a practical matter, there are people who are losing in this story, but realistically there are not a lot of people who both have substantial savings (enough that the interest makes up a big share of their income) and who kept it exclusively in short-term assets.

There are no policies to increase growth that leave no one harmed. (If you think you know of one, then you haven’t thought through the implications of the policy carefully enough.) The winners from a policy to boost growth through lower interest rates vastly outnumber the losers. The biggest grounds for complaint is that the Fed did not go far enough.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Since the Chicago school teachers went out on strike Monday, many political figures have tried to convince the public that their $70,000 average annual pay is excessive. This is peculiar, since many of the same people had been arguing that the families earning over $250,000, who would be subject to higher tax rates under President Obama’s tax proposal, are actually part of the struggling middle class. They now want to convince us that a household with two Chicago public school teachers, who together earn less than 60 percent of President Obama’s cutoff, have more money than they should.

Anyhow, if we want to assess whether someone is getting too much money, we always have to ask the follow-up question, compared to what? Here are a few comparisons that I have found useful.

Source: Author’s calculations, see text.

The first comparison number is the annualized pay that Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel got for a 14-month stint as a director at Freddie Mac. President Clinton appointed him as a director shortly after he left the administration. It’s not clear exactly what Mr. Emanuel did as a director, he was not appointed to any board committees. While Emanuel’s stint ended just as the housing bubble was building up steam, Freddie Mac was involved in an accounting scandal during this period for which it was forced to pay several million dollars in fines.

The second comparison is the compensation that Emanuel received for his day job after leaving the White House, working for Wasserstein Perella, an investment bank. According to Wikipedia, he earned $16.5 million for two and a half years of work.

The third comparison is the compensation that Erskine Bowles received as a director of Morgan Stanley, the huge Wall Street investment bank in 2008. Erskine Bowles has been mentioned in the news frequently as the co-chair of President Obama’s deficit commission. The plan that he co-authored with former Senator Alan Simpson, the other co-chair, is often held up as providing a basis for a “grand bargain” on the budget.

The year 2008 is noteworthy because this was the year that the bank was driven to the edge of bankruptcy. It was saved from imminent bankruptcy by a bailout from the Federal Reserve Board, which allowed it to change its status to become a bank holding company on an emergency basis. This gave it the protection of the Federal Reserve Board and the FDIC. Morgan Stanley also received tens of billions of dollars in below market loans and guarantees from the government. (Bowles continues to serve as a director of Morgan Stanley as well as several other companies. Here is a fuller discussion of his record as a director.)

These pay packages might be useful information for those trying to decide whether $70,000 a year is too much to pay a teacher working in inner city schools in Chicago. On the same topic, Catherine Rampell provides a useful comparison of the pay of teachers in the United States relative to the pay of teachers in other countries, most of which have better student performance on standardized exams.

Since the Chicago school teachers went out on strike Monday, many political figures have tried to convince the public that their $70,000 average annual pay is excessive. This is peculiar, since many of the same people had been arguing that the families earning over $250,000, who would be subject to higher tax rates under President Obama’s tax proposal, are actually part of the struggling middle class. They now want to convince us that a household with two Chicago public school teachers, who together earn less than 60 percent of President Obama’s cutoff, have more money than they should.

Anyhow, if we want to assess whether someone is getting too much money, we always have to ask the follow-up question, compared to what? Here are a few comparisons that I have found useful.

Source: Author’s calculations, see text.

The first comparison number is the annualized pay that Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel got for a 14-month stint as a director at Freddie Mac. President Clinton appointed him as a director shortly after he left the administration. It’s not clear exactly what Mr. Emanuel did as a director, he was not appointed to any board committees. While Emanuel’s stint ended just as the housing bubble was building up steam, Freddie Mac was involved in an accounting scandal during this period for which it was forced to pay several million dollars in fines.

The second comparison is the compensation that Emanuel received for his day job after leaving the White House, working for Wasserstein Perella, an investment bank. According to Wikipedia, he earned $16.5 million for two and a half years of work.

The third comparison is the compensation that Erskine Bowles received as a director of Morgan Stanley, the huge Wall Street investment bank in 2008. Erskine Bowles has been mentioned in the news frequently as the co-chair of President Obama’s deficit commission. The plan that he co-authored with former Senator Alan Simpson, the other co-chair, is often held up as providing a basis for a “grand bargain” on the budget.

The year 2008 is noteworthy because this was the year that the bank was driven to the edge of bankruptcy. It was saved from imminent bankruptcy by a bailout from the Federal Reserve Board, which allowed it to change its status to become a bank holding company on an emergency basis. This gave it the protection of the Federal Reserve Board and the FDIC. Morgan Stanley also received tens of billions of dollars in below market loans and guarantees from the government. (Bowles continues to serve as a director of Morgan Stanley as well as several other companies. Here is a fuller discussion of his record as a director.)

These pay packages might be useful information for those trying to decide whether $70,000 a year is too much to pay a teacher working in inner city schools in Chicago. On the same topic, Catherine Rampell provides a useful comparison of the pay of teachers in the United States relative to the pay of teachers in other countries, most of which have better student performance on standardized exams.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That might be a good question for reporters to pose to Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel given his strong stand against Chicago’s public school teachers. (It is appropriate to refer to this as a battle between Emanuel and the teachers. Almost 90 percent of the members of the bargaining unit voted to authorize a strike. This is clearly not a case of a union imposing its will on its members.) Emanuel has insisted that the schools need a major overhaul because they are badly failing Chicago’s students.

Emanual’s position is striking because Chicago’s schools had been run for seven and half years, from June of 2001 until January of 2009, by Arne Duncan. Duncan then went on to become education secretary for President Obama, based on his performance as head of the Chicago public school system. Apparently Emanuel does not believe that Duncan was very successful in improving Chicago’s schools since he claims that they are still in very bad shape.

There is no dispute that students in Chicago public schools are not faring well. Only a bit over 60 percent graduate high school in five years or less. However, this doesn’t mean that the reforms that Emanuel wants to impose will improve outcomes, just as Duncan’s reforms apparently did not have much impact, if Emanuel is to be believed.

Diana Ravitch, a one-time leading school “reformer” and assistant education secretary in the Bush administration, argues that charter schools on average perform no better than the public schools they replace. The main determinants of children’s performance continues to be the socioeconomic conditions of their parents. Those unwilling to take the steps necessary to address the latter (e.g. promote full employment) are the ones who do not care about our children.

That might be a good question for reporters to pose to Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel given his strong stand against Chicago’s public school teachers. (It is appropriate to refer to this as a battle between Emanuel and the teachers. Almost 90 percent of the members of the bargaining unit voted to authorize a strike. This is clearly not a case of a union imposing its will on its members.) Emanuel has insisted that the schools need a major overhaul because they are badly failing Chicago’s students.

Emanual’s position is striking because Chicago’s schools had been run for seven and half years, from June of 2001 until January of 2009, by Arne Duncan. Duncan then went on to become education secretary for President Obama, based on his performance as head of the Chicago public school system. Apparently Emanuel does not believe that Duncan was very successful in improving Chicago’s schools since he claims that they are still in very bad shape.

There is no dispute that students in Chicago public schools are not faring well. Only a bit over 60 percent graduate high school in five years or less. However, this doesn’t mean that the reforms that Emanuel wants to impose will improve outcomes, just as Duncan’s reforms apparently did not have much impact, if Emanuel is to be believed.

Diana Ravitch, a one-time leading school “reformer” and assistant education secretary in the Bush administration, argues that charter schools on average perform no better than the public schools they replace. The main determinants of children’s performance continues to be the socioeconomic conditions of their parents. Those unwilling to take the steps necessary to address the latter (e.g. promote full employment) are the ones who do not care about our children.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

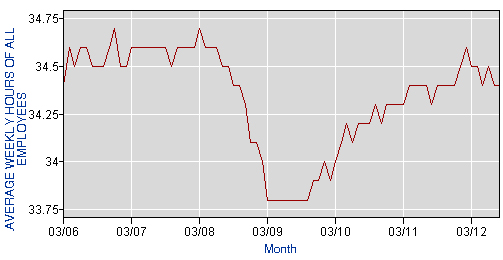

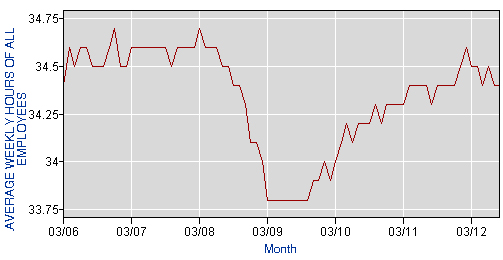

The Romney campaign has picked up a theme pushed by Republicans ever since President Obama entered the White House, employers are reluctant to hire because they are scared by regulations and taxes. Robert Samuelson picks up this line in his column assessing whether the economy can actually create 12 million jobs over the next 4 years.

There is a simple way to prove that employers have no reluctance to hire. We can look at average weekly hours. If employers are seeing increased demand but don’t want to hire because they fear an attack from the regulation monster or higher taxes, then they would work their existing work force more hours. That one should be pretty painless even for our fearful job creators. After all, do we really think that they would turn away customers from their stores, restaurants, and factories rather than have workers put in a few extra hours each week?

Here’s what the Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us about weekly hours:

Average Weekly Hours: All Employees

Source Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In short, there is no story of reluctant employers, the problem is inadequate demand pure and simple. If employers saw more demand, they would likely hire more workers.

There is one other point worth mentioning in reference to Samuelson’s evaluation of the 12 million jobs claim. Samuelson is a skeptic, noting that the economy has rarely added 3 million jobs a year in the past. That is not terribly relevant because the labor force was smaller in the past. The question is the rate of growth.

The economy did add 12 million jobs from 1996 to 2000, at a time when the labor force was almost 20 percent smaller than it is today. The 12 million jobs number is a very reasonable target. There is of course no guarantee that the economy will add this many jobs, but if we are to get back close to full employment by 2016 (8 years after the beginning of the recession) this sort of job growth will be necessary.

Addendum: The title of the graph was corrected. Also, the story here is that hours are still somewhat below their pre-recession average. That was presumably a period in which employees were not reluctant to hire because they feared taxes, regulation or whatever else. If the Romney-Samuelson story were true then hours should be above the pre-recession average. The idea is that employers would otherwise be hiring, but because of their fears about the future, they are opting not to.

The Romney campaign has picked up a theme pushed by Republicans ever since President Obama entered the White House, employers are reluctant to hire because they are scared by regulations and taxes. Robert Samuelson picks up this line in his column assessing whether the economy can actually create 12 million jobs over the next 4 years.

There is a simple way to prove that employers have no reluctance to hire. We can look at average weekly hours. If employers are seeing increased demand but don’t want to hire because they fear an attack from the regulation monster or higher taxes, then they would work their existing work force more hours. That one should be pretty painless even for our fearful job creators. After all, do we really think that they would turn away customers from their stores, restaurants, and factories rather than have workers put in a few extra hours each week?

Here’s what the Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us about weekly hours:

Average Weekly Hours: All Employees

Source Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Source Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In short, there is no story of reluctant employers, the problem is inadequate demand pure and simple. If employers saw more demand, they would likely hire more workers.

There is one other point worth mentioning in reference to Samuelson’s evaluation of the 12 million jobs claim. Samuelson is a skeptic, noting that the economy has rarely added 3 million jobs a year in the past. That is not terribly relevant because the labor force was smaller in the past. The question is the rate of growth.

The economy did add 12 million jobs from 1996 to 2000, at a time when the labor force was almost 20 percent smaller than it is today. The 12 million jobs number is a very reasonable target. There is of course no guarantee that the economy will add this many jobs, but if we are to get back close to full employment by 2016 (8 years after the beginning of the recession) this sort of job growth will be necessary.

Addendum: The title of the graph was corrected. Also, the story here is that hours are still somewhat below their pre-recession average. That was presumably a period in which employees were not reluctant to hire because they feared taxes, regulation or whatever else. If the Romney-Samuelson story were true then hours should be above the pre-recession average. The idea is that employers would otherwise be hiring, but because of their fears about the future, they are opting not to.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Post had a good article reminding people that the jobs numbers are subject to large revisions. It is always important not to make too much of a single release.

I was among those surprised by the August numbers. I expected something like the July report, with 160,000 jobs. Even that is far from great (how does full employment in 2028 sound?), but at least we would be making up some lost ground. The 96,000 jobs reported for August is just treading water, keeping pace with the growth of the labor market.

Anyhow, other data would seem to support a stronger pace of job growth. Most importantly the number of weekly unemployment claims remains near its low point for the recovery. In addition, the number of job openings reported by employers is up by more than 500,000 from year ago levels, a period in which they were adding well over 100,000 a month. Car sales and chain store sales were both pretty strong in August.

My guess is that the September number will be considerably stronger. But in any case, the Post’s warning on the monthly data is well-taken.

The Post had a good article reminding people that the jobs numbers are subject to large revisions. It is always important not to make too much of a single release.

I was among those surprised by the August numbers. I expected something like the July report, with 160,000 jobs. Even that is far from great (how does full employment in 2028 sound?), but at least we would be making up some lost ground. The 96,000 jobs reported for August is just treading water, keeping pace with the growth of the labor market.

Anyhow, other data would seem to support a stronger pace of job growth. Most importantly the number of weekly unemployment claims remains near its low point for the recovery. In addition, the number of job openings reported by employers is up by more than 500,000 from year ago levels, a period in which they were adding well over 100,000 a month. Car sales and chain store sales were both pretty strong in August.

My guess is that the September number will be considerably stronger. But in any case, the Post’s warning on the monthly data is well-taken.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

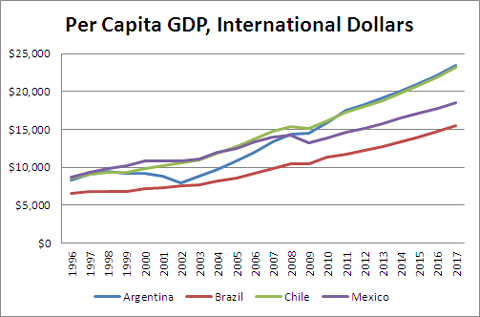

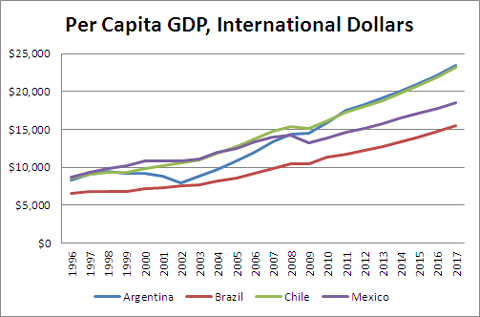

The Washington Post feels no need to observe normal journalistic standards when it comes to the NAFTA. When the trade agreement was being debated in 1993 it virtually turned the paper (both the news and opinion pages) into an advocacy organization. It continues this pattern even to this day.

As a result, when NAFTA was being debated in the Democratic primaries in 2007, it had a lead editorial in which it harshly criticized the candidates and absurdly claimed that Mexico’s GDP had quadruped since 1988. In addition to being hugely wrong (the actual growth was 83 percent according to the IMF), the choice of years was bizarre since NAFTA first took effect in 1994. To this day, the Post has never corrected this editorial.

More recently the Post has repeatedly run articles about Mexico’s fast-growing middle class. Some were published earlier this summer and it treats us to another today.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

In reality Mexico had the slowest growing economy in Latin America over the last decade, but what do you expect, it’s the Washington Post.

The Washington Post feels no need to observe normal journalistic standards when it comes to the NAFTA. When the trade agreement was being debated in 1993 it virtually turned the paper (both the news and opinion pages) into an advocacy organization. It continues this pattern even to this day.

As a result, when NAFTA was being debated in the Democratic primaries in 2007, it had a lead editorial in which it harshly criticized the candidates and absurdly claimed that Mexico’s GDP had quadruped since 1988. In addition to being hugely wrong (the actual growth was 83 percent according to the IMF), the choice of years was bizarre since NAFTA first took effect in 1994. To this day, the Post has never corrected this editorial.

More recently the Post has repeatedly run articles about Mexico’s fast-growing middle class. Some were published earlier this summer and it treats us to another today.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

In reality Mexico had the slowest growing economy in Latin America over the last decade, but what do you expect, it’s the Washington Post.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión