Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Last week This American Life had a piece on the increase in the number of people on Social Security disability. While the segment had many interesting stories, and presented useful background, it got some of the basics wrong.

While the story did note the impact of the economic downturn on disability claims, it failed to recognize the actual importance of the economic collapse. Instead the piece turned to a variety of other explanations, for example citing the 1996 welfare reform bill.

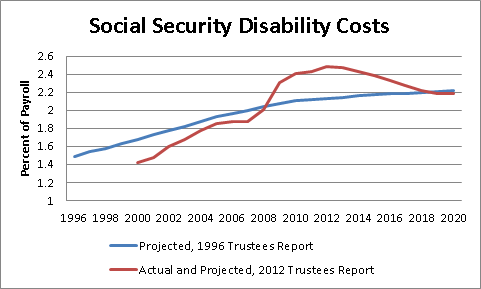

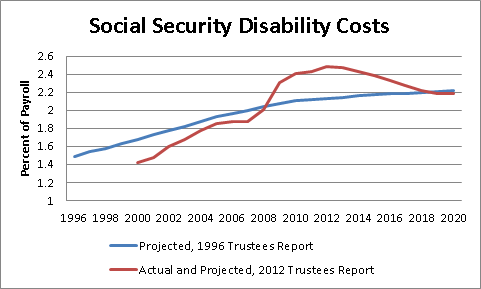

If we go back to the projections in the 1996 Social Security trustees report, the disability program was projected to cost 1.93 percent of payroll in 2005. As it turned out, the program cost just 1.85 percent of payroll in 2005, about 4 percent less than the trustees had projected in 1996. The program’s cost did explode in the downturn, rising to 2.43 percent of payroll in 2011, with a projection of 2.48 percent of payroll for last year.

Social Security Trustees Reports, 1996 and 2012.

However the explanation for this increase seems pretty clear — the economy is down almost 9 million jobs from its trend growth path. People who would have otherwise been employed find themselves desperate for any means of support due to the inept economic policy that sank the economy. This is a simple explanation that doesn’t require examining the moral turpitude of beneficiaries or evidence of corrupt or negligent administrators. Fix the economy and you would remove much of the burden on the program. It is also striking that the projections in the 2012 Trustees Report show the costs again falling below the level projected in 1996 once the unemployment rate gets back down to a more normal level.

Of course that doesn’t mean the program was working perfectly before the economic collapse. There were undoubtedly many people getting disability payments who should not have been and also many people who were wrongly denied benefits. The system is grossly understaffed. As a result, many claims take way too long to be processed and often the wrong decision is made.

However, it seems more than a bit of a reach to explain expanding disability roles on some of the items covered in the segment. For example, the welfare reform bill was passed after the projections in the 1996 Trustees report were made. Yet, in 1996 the trustees still projected that disability would cost more a decade later than turned out to be the case. If welfare reform had the effect discussed in the segment, the error should have been in the other direction.

As we say here in the nation’s capitol, it’s the economy, stupid.

Last week This American Life had a piece on the increase in the number of people on Social Security disability. While the segment had many interesting stories, and presented useful background, it got some of the basics wrong.

While the story did note the impact of the economic downturn on disability claims, it failed to recognize the actual importance of the economic collapse. Instead the piece turned to a variety of other explanations, for example citing the 1996 welfare reform bill.

If we go back to the projections in the 1996 Social Security trustees report, the disability program was projected to cost 1.93 percent of payroll in 2005. As it turned out, the program cost just 1.85 percent of payroll in 2005, about 4 percent less than the trustees had projected in 1996. The program’s cost did explode in the downturn, rising to 2.43 percent of payroll in 2011, with a projection of 2.48 percent of payroll for last year.

Social Security Trustees Reports, 1996 and 2012.

However the explanation for this increase seems pretty clear — the economy is down almost 9 million jobs from its trend growth path. People who would have otherwise been employed find themselves desperate for any means of support due to the inept economic policy that sank the economy. This is a simple explanation that doesn’t require examining the moral turpitude of beneficiaries or evidence of corrupt or negligent administrators. Fix the economy and you would remove much of the burden on the program. It is also striking that the projections in the 2012 Trustees Report show the costs again falling below the level projected in 1996 once the unemployment rate gets back down to a more normal level.

Of course that doesn’t mean the program was working perfectly before the economic collapse. There were undoubtedly many people getting disability payments who should not have been and also many people who were wrongly denied benefits. The system is grossly understaffed. As a result, many claims take way too long to be processed and often the wrong decision is made.

However, it seems more than a bit of a reach to explain expanding disability roles on some of the items covered in the segment. For example, the welfare reform bill was passed after the projections in the 1996 Trustees report were made. Yet, in 1996 the trustees still projected that disability would cost more a decade later than turned out to be the case. If welfare reform had the effect discussed in the segment, the error should have been in the other direction.

As we say here in the nation’s capitol, it’s the economy, stupid.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

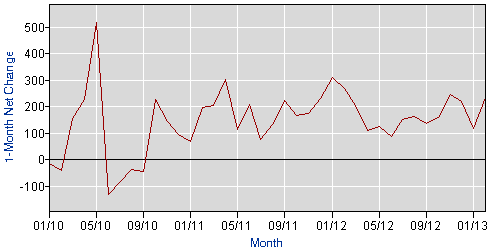

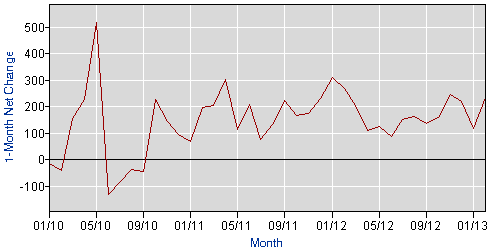

That would seem to be the case based on much of the news coverage of the Fed’s decision to continue its quantitative easing program. Many pieces have highlighted relatively positive economic reports in recent months, most notably job creation numbers. Fortunately the Fed seems to have a much better knowledge of the data than the reporters who cover it. While job growth over the last few months has been somewhat higher than the average for the recovery, it does not stand out as being especially strong.

In the last three months jobs growth has averaged 192,000. By contrast, it averaged 271,000 for the same three months a year ago. Apparently the Fed has access to this data, which it used in its decision on continuing its quantitative easing policy.

Monthly Job Growth

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Note: First sentence corrected in response to comment.

That would seem to be the case based on much of the news coverage of the Fed’s decision to continue its quantitative easing program. Many pieces have highlighted relatively positive economic reports in recent months, most notably job creation numbers. Fortunately the Fed seems to have a much better knowledge of the data than the reporters who cover it. While job growth over the last few months has been somewhat higher than the average for the recovery, it does not stand out as being especially strong.

In the last three months jobs growth has averaged 192,000. By contrast, it averaged 271,000 for the same three months a year ago. Apparently the Fed has access to this data, which it used in its decision on continuing its quantitative easing policy.

Monthly Job Growth

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Note: First sentence corrected in response to comment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT tells us that economists are struggling with cultural explanations for the fact that men’s college enrollment rates have been lagging so far behind those of women. The issue is that we have seen a sharp increase in the gap between the wages of college and high school graduates over the last three decades. What economics tells us it that this rising return to a college education should cause more people to go to college.

This is exactly what has happened with women as their rate of college enrollment and completion has increased rapidly over this period. However that has not been the case with men, who now have much lower enrollment and completion rates.

That would seem to pose somewhat of a mystery. Why do women respond to price signals but not men? M.I.T. economist David Autor seeks to find the answer in cultural differences. While there may be some truth to his explanations, there is a more simple and obvious explanation.

My colleague John Schmitt and former colleague Heather Boushey looked at this issue a couple of years ago. They noted that there was a far larger dispersion in the wages of men with college degrees than was the case with women. In fact, there was a substantial overlap between the distribution of wages of men without college degrees and men with college degrees.

This means that while on average men will have higher earnings with a college degree than without one, for a substantial portion of men this is not true. Presumably the marginal college student (the one who is deliberating over going to college versus starting their career) is more likely to be in this group of losers among college grads than the typical college student who never contemplated not attending college.

Since there is a much greater risk for men than women (who don’t have the same dispersion of wages among college grads) of ending up as losers by going to college, it should not be surprising that fewer men than women would opt to go to college. So the story is really simple, you just need a bit of economics and statistics to get there.

The NYT tells us that economists are struggling with cultural explanations for the fact that men’s college enrollment rates have been lagging so far behind those of women. The issue is that we have seen a sharp increase in the gap between the wages of college and high school graduates over the last three decades. What economics tells us it that this rising return to a college education should cause more people to go to college.

This is exactly what has happened with women as their rate of college enrollment and completion has increased rapidly over this period. However that has not been the case with men, who now have much lower enrollment and completion rates.

That would seem to pose somewhat of a mystery. Why do women respond to price signals but not men? M.I.T. economist David Autor seeks to find the answer in cultural differences. While there may be some truth to his explanations, there is a more simple and obvious explanation.

My colleague John Schmitt and former colleague Heather Boushey looked at this issue a couple of years ago. They noted that there was a far larger dispersion in the wages of men with college degrees than was the case with women. In fact, there was a substantial overlap between the distribution of wages of men without college degrees and men with college degrees.

This means that while on average men will have higher earnings with a college degree than without one, for a substantial portion of men this is not true. Presumably the marginal college student (the one who is deliberating over going to college versus starting their career) is more likely to be in this group of losers among college grads than the typical college student who never contemplated not attending college.

Since there is a much greater risk for men than women (who don’t have the same dispersion of wages among college grads) of ending up as losers by going to college, it should not be surprising that fewer men than women would opt to go to college. So the story is really simple, you just need a bit of economics and statistics to get there.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

From reading the newspapers and blogs you would think everything must be great in the country. Hey, no problems of mass unemployment, poverty, folks losing their homes, etc. How else can we explain the obsession with an aging population?

Yes, the population is aging, just as it has been aging over the last century. Yeah, we’re living longer. You got any bad news for me?

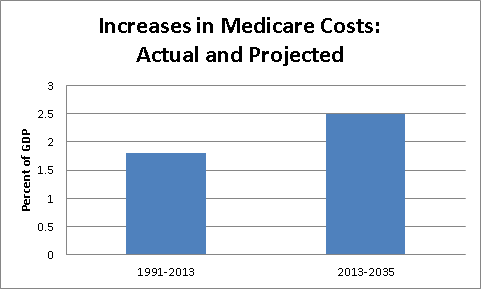

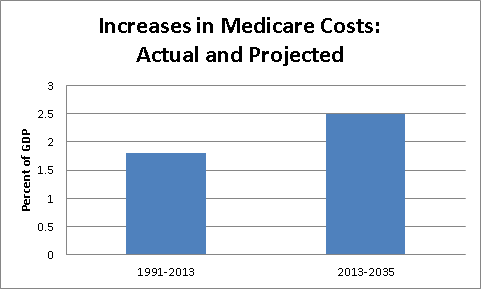

Today we have Kevin Drum and Ezra Klein giving us the bad news. It seems Medicare’s costs are projected to increase by 2.5 percentage points of GDP over the next 22 years and most of this (1.7 percentage points) is due to aging, not excess health care cost growth. Should we be worried?

Let’s look at a somewhat different graph than the one they highlight.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

What this graph tells us is that Medicare’s costs, measured as a share of GDP, increased as much in the last 22 years as they are projected to increase due to aging in the next 22 years. The rest of the increase (0.8 percentage points) is due to projected excess health care cost growth. In other words, the impact of aging alone is no more of a problem going forward than the increase in Medicare costs was for us in the last 22 years. The reason that the total cost growth is projected to be greater is entirely due to the projections of excess health care cost growth.

There are a couple of other points to be made. We would cut our health care costs roughly in half if we paid as much for our health care as any other wealthy country. This would seem to argue for increased trade in health care services. Currently the Obama administration is negotiating major trade agreements with both the European Union and with Asian countries in the Trans Pacific Partnership. How much do you want to bet that more trade in health care services is not on the list of items being addressed? When it comes to doctors and other health care providers our Washington elite types are as hard core Neanderthal protectionist as they come.

The other point is that if workers got their share of projected productivity growth over this period, wages would be around 40 percent higher in 2035 than they are today. How much do you want to bet that workers would prefer before-tax wages that are 40 percent higher with another 2 percentage points pulled out for Medicare, than stagnant wages and no tax increases?

In other words, why are serious people wasting time over this nonsense? There is much more at stake in controlling health care costs and ensuring that workers get their share of productivity growth than there is with aging.

From reading the newspapers and blogs you would think everything must be great in the country. Hey, no problems of mass unemployment, poverty, folks losing their homes, etc. How else can we explain the obsession with an aging population?

Yes, the population is aging, just as it has been aging over the last century. Yeah, we’re living longer. You got any bad news for me?

Today we have Kevin Drum and Ezra Klein giving us the bad news. It seems Medicare’s costs are projected to increase by 2.5 percentage points of GDP over the next 22 years and most of this (1.7 percentage points) is due to aging, not excess health care cost growth. Should we be worried?

Let’s look at a somewhat different graph than the one they highlight.

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

What this graph tells us is that Medicare’s costs, measured as a share of GDP, increased as much in the last 22 years as they are projected to increase due to aging in the next 22 years. The rest of the increase (0.8 percentage points) is due to projected excess health care cost growth. In other words, the impact of aging alone is no more of a problem going forward than the increase in Medicare costs was for us in the last 22 years. The reason that the total cost growth is projected to be greater is entirely due to the projections of excess health care cost growth.

There are a couple of other points to be made. We would cut our health care costs roughly in half if we paid as much for our health care as any other wealthy country. This would seem to argue for increased trade in health care services. Currently the Obama administration is negotiating major trade agreements with both the European Union and with Asian countries in the Trans Pacific Partnership. How much do you want to bet that more trade in health care services is not on the list of items being addressed? When it comes to doctors and other health care providers our Washington elite types are as hard core Neanderthal protectionist as they come.

The other point is that if workers got their share of projected productivity growth over this period, wages would be around 40 percent higher in 2035 than they are today. How much do you want to bet that workers would prefer before-tax wages that are 40 percent higher with another 2 percentage points pulled out for Medicare, than stagnant wages and no tax increases?

In other words, why are serious people wasting time over this nonsense? There is much more at stake in controlling health care costs and ensuring that workers get their share of productivity growth than there is with aging.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The medical device industry is pushing hard to repeal a tax imposed as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The NYT had an article on its massive bipartisan lobbying effort. While the piece notes in passing that, “the White House argues that demand for new devices will offset the economic impact of the tax,” the piece doesn’t explain what this means.

The marginal cost of producing most medical devices is very low relative to their price. The companies are in effect collecting a big premium because of their patent monopolies. The ACA meant that they would sell many more devices and therefore collect a much higher dividend from their patents, even though the amount spent on research had not changed.

To see the logic here, imagine that it costs a medical company nothing to produce a scanner that it will sell for $1 million apiece. (Again, the high price is allowing it to recover development costs.) Before the ACA it would have expected to sell 1000 scanners, netting it $1 billion. After the ACA the company can expect to sell 1100 scanners, netting it $1.1 billion.

The tax is intended to recoup this additional $100 million. While the tax hit will not be exactly offsetting to the increased profit to the industry in every case, on average this will be the case. In other words, the White House is not making a bizarre argument, they are presenting the facts. The industry is trying to pocket extra profits as a dividend from the ACA and does not want the government to tax back part, or all, of this dividend.

The medical device industry is pushing hard to repeal a tax imposed as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The NYT had an article on its massive bipartisan lobbying effort. While the piece notes in passing that, “the White House argues that demand for new devices will offset the economic impact of the tax,” the piece doesn’t explain what this means.

The marginal cost of producing most medical devices is very low relative to their price. The companies are in effect collecting a big premium because of their patent monopolies. The ACA meant that they would sell many more devices and therefore collect a much higher dividend from their patents, even though the amount spent on research had not changed.

To see the logic here, imagine that it costs a medical company nothing to produce a scanner that it will sell for $1 million apiece. (Again, the high price is allowing it to recover development costs.) Before the ACA it would have expected to sell 1000 scanners, netting it $1 billion. After the ACA the company can expect to sell 1100 scanners, netting it $1.1 billion.

The tax is intended to recoup this additional $100 million. While the tax hit will not be exactly offsetting to the increased profit to the industry in every case, on average this will be the case. In other words, the White House is not making a bizarre argument, they are presenting the facts. The industry is trying to pocket extra profits as a dividend from the ACA and does not want the government to tax back part, or all, of this dividend.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post has a piece puzzling over the fact that:

“Builders started work on 27.7 percent more homes in February than they did a year earlier. Yet the number of construction jobs in the United States was only 2.9 percent higher, year-over-year.”

The Post turned to analysts at Goldman Sachs who concluded that the answer was labor hoarding. They make a case that firms are changing the length of the workweek to meet the increased demand for labor rather than adding more workers. This one doesn’t fly.

First, residential construction is a comparatively low-paying sector with casual labor relations. This is not General Motors with union contracts that make layoffs difficult. In other words, it is not a sector where we would expect to see a lot of labor hoarding.

The data on hours shown in the piece also do not support the labor hoarding story. While the average workweek has increased by roughly 3 hours since the trough of the downturn in 2009, it is up by only about 0.5 hours since 2011, which means that it would be equivalent to an increase in employment of less than 2 percent. That will not fill much of the gap identified in the piece.

So, what’s the real story? First, total construction is up by much less than residential construction. The Commerce Department reported that total nominal construction was 7.1 percent higher in January of 2013 than January of 2012. In real terms this would be a rise of around 5.0 percent, not too different from the increase in employment.

The other big issue is that many of the workers employed in residential construction are undocumented and may not show up in the payroll data. In fact, there was a sharp decline in residential construction in 2006 and 2007 even as employment in construction was still growing. From its peak in 2005 to the end of 2007 housing starts fell by almost 40 percent, while construction employment was little changed. Given this history, there is no reason to expect a big upturn in employment in response to the relatively small rise in starts that we have seen in the last year.

Click for larger version

The Washington Post has a piece puzzling over the fact that:

“Builders started work on 27.7 percent more homes in February than they did a year earlier. Yet the number of construction jobs in the United States was only 2.9 percent higher, year-over-year.”

The Post turned to analysts at Goldman Sachs who concluded that the answer was labor hoarding. They make a case that firms are changing the length of the workweek to meet the increased demand for labor rather than adding more workers. This one doesn’t fly.

First, residential construction is a comparatively low-paying sector with casual labor relations. This is not General Motors with union contracts that make layoffs difficult. In other words, it is not a sector where we would expect to see a lot of labor hoarding.

The data on hours shown in the piece also do not support the labor hoarding story. While the average workweek has increased by roughly 3 hours since the trough of the downturn in 2009, it is up by only about 0.5 hours since 2011, which means that it would be equivalent to an increase in employment of less than 2 percent. That will not fill much of the gap identified in the piece.

So, what’s the real story? First, total construction is up by much less than residential construction. The Commerce Department reported that total nominal construction was 7.1 percent higher in January of 2013 than January of 2012. In real terms this would be a rise of around 5.0 percent, not too different from the increase in employment.

The other big issue is that many of the workers employed in residential construction are undocumented and may not show up in the payroll data. In fact, there was a sharp decline in residential construction in 2006 and 2007 even as employment in construction was still growing. From its peak in 2005 to the end of 2007 housing starts fell by almost 40 percent, while construction employment was little changed. Given this history, there is no reason to expect a big upturn in employment in response to the relatively small rise in starts that we have seen in the last year.

Click for larger version

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A Morning Edition piece on the housing market blamed difficulties in the housing market in part on people being unable to get mortgages because of inaccurate appraisals. In fact, this should not on average reduce sales. While some sales will be prevented by an appraisal that wrongly comes in too low, some sales will go through that should not because an inaccurate appraisal comes in too high. Unless there is some reason there is a low side bias to the appraisals, inaccuracy by itself should not affect total sales.

A Morning Edition piece on the housing market blamed difficulties in the housing market in part on people being unable to get mortgages because of inaccurate appraisals. In fact, this should not on average reduce sales. While some sales will be prevented by an appraisal that wrongly comes in too low, some sales will go through that should not because an inaccurate appraisal comes in too high. Unless there is some reason there is a low side bias to the appraisals, inaccuracy by itself should not affect total sales.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión