George Will, who likes to mock any and everything the government does, has apparently decided that it is very good at supporting scientific research. He is outraged over the sequester, which is bringing a halt to several major research projects at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

This is truly a fascinating line of argument from Will. He says that we need the government to do this research because it will not produce near term benefits:

“In the private sector, where investors expect a quick turnaround, it is difficult to find dollars for a 10-year program.”

Okay, but this argument implies that the government is not necessarily run by a bunch of bozos. If it were then giving money to NIH would be the same thing as throwing it in the toilet. This means that Will thinks that money spent at NIH actually has useful benefits.

Now let’s carry this logic one step further. Suppose we gave additional funding, not just for basic research, but for actually developing drugs and bringing them through the clinical testing and FDA approval process. We already have Will on record saying that NIH is not run by bozos, so this means that he must think that we can in principle replace the patent supporting research by Pfizer, Merck and the other drug companies with funding from the government. (This doesn’t mean the government does the research. It could contract out the research, possibly even with Pfizer and Merck.) Let’s even hypothesize for the sake of argument, that a dollar of research funding supported by patent monopolies is more efficient than a dollar of funding that passes through the government.

In order to compare the publicly funded route with the patent supported route we would have to weigh the relative efficiency of the research dollars under the two systems with the enormous waste associated with patent monopolies. If a drug was developed through a publicly supported system then it could immediately be sold as a generic for $5 to $10 per prescription instead of selling for hundreds or even thousands of dollars per prescription. No drug company would have an incentive to lie about its effectiveness or hype the drug for inappropriate uses. Also, nearly everyone would be able to get access to the drug without haggling with insurers or government agencies.

In fact, the public system would have advantages in the research process itself. A condition of public support could be that all research findings are publicly posted on the web as soon as practical. This would allow researchers to learn from each others’ successes and failures and to avoid unnecessary duplication. That will not happen with patent supported research where all the findings are proprietary information.

These are the sorts of questions about drug research that serious people would ask if they acknowledge that the government can usefully fund research. But don’t expect to see such follow up questions posed either by Will or anyone else in the Washington Post (except in Wonkblog).

George Will, who likes to mock any and everything the government does, has apparently decided that it is very good at supporting scientific research. He is outraged over the sequester, which is bringing a halt to several major research projects at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

This is truly a fascinating line of argument from Will. He says that we need the government to do this research because it will not produce near term benefits:

“In the private sector, where investors expect a quick turnaround, it is difficult to find dollars for a 10-year program.”

Okay, but this argument implies that the government is not necessarily run by a bunch of bozos. If it were then giving money to NIH would be the same thing as throwing it in the toilet. This means that Will thinks that money spent at NIH actually has useful benefits.

Now let’s carry this logic one step further. Suppose we gave additional funding, not just for basic research, but for actually developing drugs and bringing them through the clinical testing and FDA approval process. We already have Will on record saying that NIH is not run by bozos, so this means that he must think that we can in principle replace the patent supporting research by Pfizer, Merck and the other drug companies with funding from the government. (This doesn’t mean the government does the research. It could contract out the research, possibly even with Pfizer and Merck.) Let’s even hypothesize for the sake of argument, that a dollar of research funding supported by patent monopolies is more efficient than a dollar of funding that passes through the government.

In order to compare the publicly funded route with the patent supported route we would have to weigh the relative efficiency of the research dollars under the two systems with the enormous waste associated with patent monopolies. If a drug was developed through a publicly supported system then it could immediately be sold as a generic for $5 to $10 per prescription instead of selling for hundreds or even thousands of dollars per prescription. No drug company would have an incentive to lie about its effectiveness or hype the drug for inappropriate uses. Also, nearly everyone would be able to get access to the drug without haggling with insurers or government agencies.

In fact, the public system would have advantages in the research process itself. A condition of public support could be that all research findings are publicly posted on the web as soon as practical. This would allow researchers to learn from each others’ successes and failures and to avoid unnecessary duplication. That will not happen with patent supported research where all the findings are proprietary information.

These are the sorts of questions about drug research that serious people would ask if they acknowledge that the government can usefully fund research. But don’t expect to see such follow up questions posed either by Will or anyone else in the Washington Post (except in Wonkblog).

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post ran an article on Bill Daley’s decision to run for the Democratic nomination for governor in Illinois. The piece notes that Daley is the son of former Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley and the brother of another former mayor, Richard M. Daley.

It probably would have been worth noting that latter connection is not likely to play especially well right now. Richard M. Daley failed to make the required contributions to the city’s pension funds for his last decade in office, leaving them underfunded by more than $27 billion. (This includes the teacher’s fund, which comes from a separate budget.) The current mayor, Rahm Emmanual claims that this is an unpayable burden and want to default on the city’s debt to these funds. (The workers and their unions strongly object to this plan and will fight any default in court.)

Regardless of the outcome of this dispute, allowing pensions to become as underfunded as Chicago’s was remarkably irresponsible, especially in a city such as Chicago with a relatively healthy economy. There are few big city mayors who have been more reckless with public finances in recent decades.

It is probably also worth noting that Emanual has claimed that the city’s schools were a disaster when he came into office. The schools had been under Daley’s direct control for most of his 22 years in office.

The Washington Post ran an article on Bill Daley’s decision to run for the Democratic nomination for governor in Illinois. The piece notes that Daley is the son of former Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley and the brother of another former mayor, Richard M. Daley.

It probably would have been worth noting that latter connection is not likely to play especially well right now. Richard M. Daley failed to make the required contributions to the city’s pension funds for his last decade in office, leaving them underfunded by more than $27 billion. (This includes the teacher’s fund, which comes from a separate budget.) The current mayor, Rahm Emmanual claims that this is an unpayable burden and want to default on the city’s debt to these funds. (The workers and their unions strongly object to this plan and will fight any default in court.)

Regardless of the outcome of this dispute, allowing pensions to become as underfunded as Chicago’s was remarkably irresponsible, especially in a city such as Chicago with a relatively healthy economy. There are few big city mayors who have been more reckless with public finances in recent decades.

It is probably also worth noting that Emanual has claimed that the city’s schools were a disaster when he came into office. The schools had been under Daley’s direct control for most of his 22 years in office.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Paul Krugman devotes his column today to the unreality of the debate in Washington on the budget and the deficit. Towards the end of the piece he refers Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson the co-chairs of President Obama’s deficit commission:

“People like Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles, the co-chairmen of President Obama’s deficit commission, did a lot to feed public anxiety about the deficit when it was high. Their report was ominously titled ‘The Moment of Truth.'”

While Krugman is correct in referring to the report as “their report,” Simpson and Bowles were not so honest. The website for the commission refers to the report as the “report of the national commission on fiscal responsibility and reform.” However, this is not true.

Those who prefer truth to truthiness might notice that the bylaws say:

“The Commission shall vote on the approval of a final report containing a set of recommendations to achieve the objectives set forth in the Charter no later than December 1, 2010. The issuance of a final report of the Commission shall require the approval of not less than 14 of the 18 members of the Commission.”

There in fact is no record of an official vote of the commisssion and certainly not by the December 1, 2010 deadline. There was an informal vote of December 3rd, in which 11 of the commission’s members, 3 fewer than required under the by-laws, voted in favor of the final report.

Therefore under the bylaws that govern the operation of the commission, there was no final report. In other words, the “moment of truth” was a lie. The report that appears as the commission’s “report” is not in fact a report of the commission.

Paul Krugman devotes his column today to the unreality of the debate in Washington on the budget and the deficit. Towards the end of the piece he refers Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson the co-chairs of President Obama’s deficit commission:

“People like Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles, the co-chairmen of President Obama’s deficit commission, did a lot to feed public anxiety about the deficit when it was high. Their report was ominously titled ‘The Moment of Truth.'”

While Krugman is correct in referring to the report as “their report,” Simpson and Bowles were not so honest. The website for the commission refers to the report as the “report of the national commission on fiscal responsibility and reform.” However, this is not true.

Those who prefer truth to truthiness might notice that the bylaws say:

“The Commission shall vote on the approval of a final report containing a set of recommendations to achieve the objectives set forth in the Charter no later than December 1, 2010. The issuance of a final report of the Commission shall require the approval of not less than 14 of the 18 members of the Commission.”

There in fact is no record of an official vote of the commisssion and certainly not by the December 1, 2010 deadline. There was an informal vote of December 3rd, in which 11 of the commission’s members, 3 fewer than required under the by-laws, voted in favor of the final report.

Therefore under the bylaws that govern the operation of the commission, there was no final report. In other words, the “moment of truth” was a lie. The report that appears as the commission’s “report” is not in fact a report of the commission.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Readers might think that they would after reading Wonkblog’s piece, “Five facts about household debt in the United States.” The piece begins by telling readers:

“The U.S. economy has been growing glacially for the last four years. And, by almost all tellings, the overhang of debt from the pre-crisis years is a big part of the reason why.”

Is that so? There seems to be a very simple story that does not hinge on debt overhang. When the housing bubble collapsed it destroyed $8 trillion iin housing wealth. This bubble wealth was driving the economy in two ways.

First, record high house prices led to an extraordinary construction boom. Residential construction, which is normally around 3.5 percent of GDP, surged to more than 6.0 percent of GDP at its peak in 2005. After the collapse of the bubble, the overbuilding led to a period of well-below-normal levels, with construction falling to less than 2.0 percent of GDP. The difference of more than 4 percentage points of GDP implies a loss in annual demand of around $640 billion in today’s economy. (Residential construction is now recovering and is currently a bit more than 3.0 percent of GDP.)

The other way that the housing bubble was driving the economy was through the housing wealth effect. Economists estimate that homeowners increase their consumption by 5-7 cents for each additional dollar of home equity. This would imply that bubble wealth increased annual consumption by $400 to $560 billion a year. When the bubble wealth disappeared, so did this excess consumption.

The question then is where does debt figure into this picture? The answer is it doesn’t really. People will spend based on their equity, net of debt. This means that we would expect a person with a $300,000 home and a $100,000 mortgage to spend roughly the same amount as a result of her housing equity as a person with a $200,000 home and no mortgage. It is the amount of equity that matters, not the amount of debt.

This doesn’t mean that there may not be some differences across households. If the value of Bill Gates’ home rises by $10 million, it would probably have less effect on consumption than if 100 miiddle income homeowners saw the price of their homes increase by an average of $100,000. But this has nothing directly to do with debt. It is a question of the distribution of wealth.

In fact, it is just wrong to imply that consumption is currently depressed. It isn’t. The saving rate in the first half of 2013 was less than 4.3 percent. This is less than half of the average saving rate in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. It is lower than the saving rate at any points in the post-ware era except the peaks of the stock and housing bubbles. Unless we see a return of a bubble, there is no reason to expect consumption to increase further relative to income.

The reality is, consumption is high, not low. This is yet another which way is up problem in economics.

We still see a slump because of the unmentionable trade deficit. We need a source of demand to replace the demand lost to this deficit, as widely recognized by fans of national income accounting everywhere.

Readers might think that they would after reading Wonkblog’s piece, “Five facts about household debt in the United States.” The piece begins by telling readers:

“The U.S. economy has been growing glacially for the last four years. And, by almost all tellings, the overhang of debt from the pre-crisis years is a big part of the reason why.”

Is that so? There seems to be a very simple story that does not hinge on debt overhang. When the housing bubble collapsed it destroyed $8 trillion iin housing wealth. This bubble wealth was driving the economy in two ways.

First, record high house prices led to an extraordinary construction boom. Residential construction, which is normally around 3.5 percent of GDP, surged to more than 6.0 percent of GDP at its peak in 2005. After the collapse of the bubble, the overbuilding led to a period of well-below-normal levels, with construction falling to less than 2.0 percent of GDP. The difference of more than 4 percentage points of GDP implies a loss in annual demand of around $640 billion in today’s economy. (Residential construction is now recovering and is currently a bit more than 3.0 percent of GDP.)

The other way that the housing bubble was driving the economy was through the housing wealth effect. Economists estimate that homeowners increase their consumption by 5-7 cents for each additional dollar of home equity. This would imply that bubble wealth increased annual consumption by $400 to $560 billion a year. When the bubble wealth disappeared, so did this excess consumption.

The question then is where does debt figure into this picture? The answer is it doesn’t really. People will spend based on their equity, net of debt. This means that we would expect a person with a $300,000 home and a $100,000 mortgage to spend roughly the same amount as a result of her housing equity as a person with a $200,000 home and no mortgage. It is the amount of equity that matters, not the amount of debt.

This doesn’t mean that there may not be some differences across households. If the value of Bill Gates’ home rises by $10 million, it would probably have less effect on consumption than if 100 miiddle income homeowners saw the price of their homes increase by an average of $100,000. But this has nothing directly to do with debt. It is a question of the distribution of wealth.

In fact, it is just wrong to imply that consumption is currently depressed. It isn’t. The saving rate in the first half of 2013 was less than 4.3 percent. This is less than half of the average saving rate in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. It is lower than the saving rate at any points in the post-ware era except the peaks of the stock and housing bubbles. Unless we see a return of a bubble, there is no reason to expect consumption to increase further relative to income.

The reality is, consumption is high, not low. This is yet another which way is up problem in economics.

We still see a slump because of the unmentionable trade deficit. We need a source of demand to replace the demand lost to this deficit, as widely recognized by fans of national income accounting everywhere.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is standard practice in elite circles to blame U.S. workers for their lack of jobs and low wages. The problem is they lack the right skills to compete in the global economy. The NYT gave us another example of this complaint with Stephan Richter’s column today.

While it would be desirable to have a better trained and educated workforce, the reason why our manufacturing workers lose out to international competition, while highly educated workers like doctors and lawyers don’t, is that the latter are highly protected. By contrast, it has been explicit policy to put manufacturing workers in direct competition with the lowest paid workers in the developing world.

If we had free traders directing policy, our trade deals would have been as focused on removing the barriers that make it difficult for smart and ambituous kids in the developing world from becoming doctors, dentists, and lawyers in the United States. This would have driven down wages in these fields and led to enormous savings to consumers on health care, legal fees and other professional services. However trade policy in the United States has been dominated by protectionists who want to limit competition for the most highly paid workers, while using international competition to drive down the wages for those workers at the middle and bottom of the pay ladder.

It is standard practice in elite circles to blame U.S. workers for their lack of jobs and low wages. The problem is they lack the right skills to compete in the global economy. The NYT gave us another example of this complaint with Stephan Richter’s column today.

While it would be desirable to have a better trained and educated workforce, the reason why our manufacturing workers lose out to international competition, while highly educated workers like doctors and lawyers don’t, is that the latter are highly protected. By contrast, it has been explicit policy to put manufacturing workers in direct competition with the lowest paid workers in the developing world.

If we had free traders directing policy, our trade deals would have been as focused on removing the barriers that make it difficult for smart and ambituous kids in the developing world from becoming doctors, dentists, and lawyers in the United States. This would have driven down wages in these fields and led to enormous savings to consumers on health care, legal fees and other professional services. However trade policy in the United States has been dominated by protectionists who want to limit competition for the most highly paid workers, while using international competition to drive down the wages for those workers at the middle and bottom of the pay ladder.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

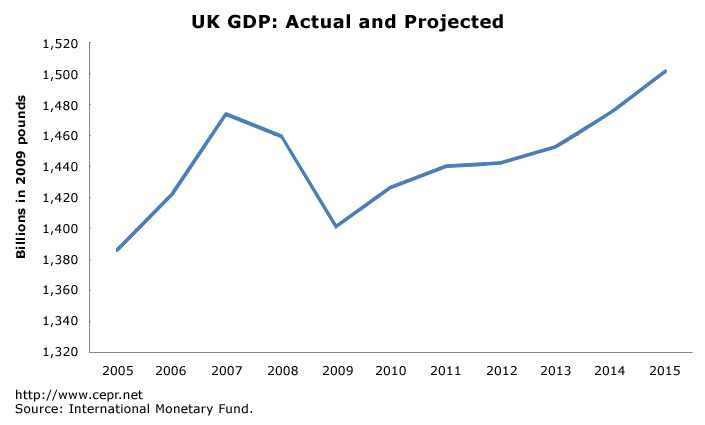

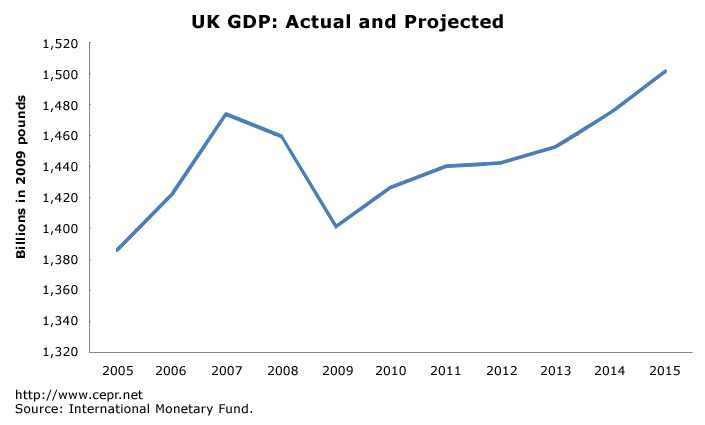

The NYT ran a Reuters piece touting the UK’s return to growth after enduring a prolonged period of recession and stagnation. It would have been worth mentioning that even on its current path, the UK will just be passing its 2008 level of output in 2014. Even with the return to growth, the IMF projects that per capita GDP in the UK will not pass its 2007 level until 2018.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

The NYT ran a Reuters piece touting the UK’s return to growth after enduring a prolonged period of recession and stagnation. It would have been worth mentioning that even on its current path, the UK will just be passing its 2008 level of output in 2014. Even with the return to growth, the IMF projects that per capita GDP in the UK will not pass its 2007 level until 2018.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s a good question, but this Washington Post article probably won’t help people answer it. A 0.3 percent growth rate sounds depressingly close to zero, but in fact this number refers to the quarterly growth, not the annual growth rate, which is the standard way of reporting growth numbers in the United States.

This one should be really simple. GDP growth data in the U.S. is always reported as an annual rate. Did anyone see a report that the U.S. economy grew 0.4 percent in the second quarter? Multiplying by four will quickly transform these quarterly growth numbers into annual rates. (Okay, to be precise you want to take the growth to the fourth power, as in 1.003^4.) There is no excuse for not reporting GDP growth numbers in a way that would make their meaning clear to most readers.

FWIW, I can’t tell you whether the euro zone should be happy or mourning its 1.2 percent growth rate in the second quarter. Given the severity of its downturn, it’s not much of a bounceback. On the other hand, it is certainly better than seeing another fall in output.

That’s a good question, but this Washington Post article probably won’t help people answer it. A 0.3 percent growth rate sounds depressingly close to zero, but in fact this number refers to the quarterly growth, not the annual growth rate, which is the standard way of reporting growth numbers in the United States.

This one should be really simple. GDP growth data in the U.S. is always reported as an annual rate. Did anyone see a report that the U.S. economy grew 0.4 percent in the second quarter? Multiplying by four will quickly transform these quarterly growth numbers into annual rates. (Okay, to be precise you want to take the growth to the fourth power, as in 1.003^4.) There is no excuse for not reporting GDP growth numbers in a way that would make their meaning clear to most readers.

FWIW, I can’t tell you whether the euro zone should be happy or mourning its 1.2 percent growth rate in the second quarter. Given the severity of its downturn, it’s not much of a bounceback. On the other hand, it is certainly better than seeing another fall in output.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Neil Irwin has a discussion of the growth potential of the U.S. economy that follows the work of two JP Morgan economists. The basic story is quite pessimistic, arguing that we will see rapid declines in labor force participation and much slower productivity growth in the future. I won’t comment on these points at length here (the evidence presented is limited in the piece and weak), but will rather focus on the conclusion.

The piece ends by warning readers:

“And if the analysis is right, and we have downshifted to a slower pace of potential growth, we will hit the speed limit of this recovery — the point at which inflation becomes a risk — sooner than forecasters are commonly thinking.”

The standard theory about the causes of inflation is based on the unemployment rates. Folks have probably heard of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU). The logic of this theory is that at lower rates of unemployment there is more upward pressure on wages and prices, meaning that the inflation rate increases. At higher rates of unemployment there is less upward pressure on wages and prices, which means the rate of inflation decreases.

The NAIRU is that wonderful level of unemployment at which the inflation rate will stay constant. For true believers, it is the unemployment rate that the Fed would target since it is the lowest unemployment consistent with a stable rate of inflation.

There are lots of good criticisms of this view, but some permutation of it dominates the vast majority of mainstream thinking about the economy. Note that it does not say anything about growth. The non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment is a story about unemployment, as the name implies.

Growth can enter into the picture if the unemployment rate is actually at the NAIRU. In this situation, if the economy grows at a rate faster than its potential (it can do this for short periods of time), then the unemployment rate would fall below the NAIRU and we would then see accelerating inflation. But the key variable in this picture is still unemployment, not growth.

This is important for two reasons. First, there is no limit on the economy’s ability to acheive rapid growth as long as we have an unemployment rate above the NAIRU. Even if the rate of growth of potential GDP is just 2.0 percent, the economy can still have a spurt of 6 percent, 7 percent, or even 8 percent, as long as there is large amounts of slack in the economy, as is the case today.

The other point is that unemployment is something that people see and experience. Growth is not. The key economic debate is how low the unemployment rate can go — how many people can have jobs — not how fast the economy can grow. We will find that out when we get the unemployment rate as low as possible without serious problems with inflation.

Neil Irwin has a discussion of the growth potential of the U.S. economy that follows the work of two JP Morgan economists. The basic story is quite pessimistic, arguing that we will see rapid declines in labor force participation and much slower productivity growth in the future. I won’t comment on these points at length here (the evidence presented is limited in the piece and weak), but will rather focus on the conclusion.

The piece ends by warning readers:

“And if the analysis is right, and we have downshifted to a slower pace of potential growth, we will hit the speed limit of this recovery — the point at which inflation becomes a risk — sooner than forecasters are commonly thinking.”

The standard theory about the causes of inflation is based on the unemployment rates. Folks have probably heard of the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU). The logic of this theory is that at lower rates of unemployment there is more upward pressure on wages and prices, meaning that the inflation rate increases. At higher rates of unemployment there is less upward pressure on wages and prices, which means the rate of inflation decreases.

The NAIRU is that wonderful level of unemployment at which the inflation rate will stay constant. For true believers, it is the unemployment rate that the Fed would target since it is the lowest unemployment consistent with a stable rate of inflation.

There are lots of good criticisms of this view, but some permutation of it dominates the vast majority of mainstream thinking about the economy. Note that it does not say anything about growth. The non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment is a story about unemployment, as the name implies.

Growth can enter into the picture if the unemployment rate is actually at the NAIRU. In this situation, if the economy grows at a rate faster than its potential (it can do this for short periods of time), then the unemployment rate would fall below the NAIRU and we would then see accelerating inflation. But the key variable in this picture is still unemployment, not growth.

This is important for two reasons. First, there is no limit on the economy’s ability to acheive rapid growth as long as we have an unemployment rate above the NAIRU. Even if the rate of growth of potential GDP is just 2.0 percent, the economy can still have a spurt of 6 percent, 7 percent, or even 8 percent, as long as there is large amounts of slack in the economy, as is the case today.

The other point is that unemployment is something that people see and experience. Growth is not. The key economic debate is how low the unemployment rate can go — how many people can have jobs — not how fast the economy can grow. We will find that out when we get the unemployment rate as low as possible without serious problems with inflation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Readers of the Financial Times will undoubtedly be looking for this headline in future editions after seeing that:

“Berlin and Brussels credit fiscal discipline and reform for euro zone recovery.”

As predicted by non-members of the flat earth society everywhere, the “fiscal discipline” pushed by Berlin and Brussels has led to severe recessions across much of Europe.The story is very simple. In the middle of a severe downturn, cutting back government spending and/or raising taxes lowers demand. There is no reason to think that firms will invest more or consumers will buy more simply because the government is spending less. Recent research from the IMF has confirmed this to be the case.

But just as any non-fatal beating eventually ends, the decline in GDP due to government cutbacks may finally have reached an endpoint.

Apparently in Berlin and Brussels they consider it cause for celebration that their policies did not lead to a permanently declining economy. This is known as the soft bigotry of incredibly low expectations.

Readers of the Financial Times will undoubtedly be looking for this headline in future editions after seeing that:

“Berlin and Brussels credit fiscal discipline and reform for euro zone recovery.”

As predicted by non-members of the flat earth society everywhere, the “fiscal discipline” pushed by Berlin and Brussels has led to severe recessions across much of Europe.The story is very simple. In the middle of a severe downturn, cutting back government spending and/or raising taxes lowers demand. There is no reason to think that firms will invest more or consumers will buy more simply because the government is spending less. Recent research from the IMF has confirmed this to be the case.

But just as any non-fatal beating eventually ends, the decline in GDP due to government cutbacks may finally have reached an endpoint.

Apparently in Berlin and Brussels they consider it cause for celebration that their policies did not lead to a permanently declining economy. This is known as the soft bigotry of incredibly low expectations.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT devoted an article to Germany’s declining population, which it warns may lead to a “major labor shortage” according to unnamed experts. The piece warns that this is not only a potential crisis for Germany, but in fact all of Europe, telling readers:

“There is little doubt about the urgency of the crisis for Europe.”

The piece is confused throughout, apparently misunderstanding the way markets work. At one point it tells readers that German employers have “hundreds of thousands of skilled jobs unfilled.” In fact this just means that these employers are unwilling to pay the market wage for these jobs.

That happens all the time as economies evolve. The reason that half of the U.S. workforce does not work in agriculture is that farmers had millions of jobs unfilled because workers could get better paying jobs in cities. The farmers that went out of business were undoubtedly made unhappy by being unable to get low cost labor for their farms, but it’s unlikely the NYT called it a crisis as it was happening.

If the labor market tightens in response to a declining population then low productivity jobs will go unfilled. For example, there will be fewer clerks in retail stores to assist customers and many restaurants will close since restaurant workers will be able to get higher wages. If the jobs that are unfilled are important to the economy, then presumably employers will offer higher wages and be able to pull workers away from other jobs or persuade more workers to get the skills necessary for the positions.

The other misleading fear story in this picture is the idea that a declining working age population will not be able to support a larger population of retirees:

“There are about four workers for every pensioner in the European Union. By 2060, the average will drop to two, according to the European Union’s 2012 report on aging.”

This is bizarre for several reasons. First, right now Europe is suffering enormously because it has way too many workers to support its population of retirees, which is why countries like Spain and Italy have double-digit unemployment (25 percent in the case of Spain). It’s understandable that labor shortages would not figure prominently as a concern to many Europeans just now.

However, the underlying arithmetic here is also misleading. Countries have dealt with declining ratios of workers to retirees for close to a century, and for the most part without much difficulty. In the United States the ratio fell from 5 to 1 in 1960 to just 2.8 to 1 in 2012. This did not prevent large improvements in living standards for both workers and retirees. It is hard to see why a comparable drop in the next 50 years in the European Union would lead to serious disruptions. (Actually it is surprising that the ratio of workers to retirees is so much higher in Europe than the United States since the EU does have an older population.)

Simple arithmetic shows that the impact of productivity growth will swamp the impact of demographics. If a retiree gets 80 percent of the income of an average worker, then it is necessary to have a tax rate (or its equivalent) of just under 17 percent on workers when the ratio of workers to retiree is 4 to 1. The necessary tax rate would be a bit less than 29 percent if the ratio is just 2 to 1.

If the country is able to maintain just a 1.5 percent rate of productivity growth over this 50 year period (the pace of growth during the slowdown period in the United States) and wages keep pace with productivity growth, then before tax wages will be 110 percent higher in 2062 than they are today. This would leave after-tax wages more than 80 percent higher than today. It’s difficult to see why Europeans should be viewing this as a crisis.

The NYT devoted an article to Germany’s declining population, which it warns may lead to a “major labor shortage” according to unnamed experts. The piece warns that this is not only a potential crisis for Germany, but in fact all of Europe, telling readers:

“There is little doubt about the urgency of the crisis for Europe.”

The piece is confused throughout, apparently misunderstanding the way markets work. At one point it tells readers that German employers have “hundreds of thousands of skilled jobs unfilled.” In fact this just means that these employers are unwilling to pay the market wage for these jobs.

That happens all the time as economies evolve. The reason that half of the U.S. workforce does not work in agriculture is that farmers had millions of jobs unfilled because workers could get better paying jobs in cities. The farmers that went out of business were undoubtedly made unhappy by being unable to get low cost labor for their farms, but it’s unlikely the NYT called it a crisis as it was happening.

If the labor market tightens in response to a declining population then low productivity jobs will go unfilled. For example, there will be fewer clerks in retail stores to assist customers and many restaurants will close since restaurant workers will be able to get higher wages. If the jobs that are unfilled are important to the economy, then presumably employers will offer higher wages and be able to pull workers away from other jobs or persuade more workers to get the skills necessary for the positions.

The other misleading fear story in this picture is the idea that a declining working age population will not be able to support a larger population of retirees:

“There are about four workers for every pensioner in the European Union. By 2060, the average will drop to two, according to the European Union’s 2012 report on aging.”

This is bizarre for several reasons. First, right now Europe is suffering enormously because it has way too many workers to support its population of retirees, which is why countries like Spain and Italy have double-digit unemployment (25 percent in the case of Spain). It’s understandable that labor shortages would not figure prominently as a concern to many Europeans just now.

However, the underlying arithmetic here is also misleading. Countries have dealt with declining ratios of workers to retirees for close to a century, and for the most part without much difficulty. In the United States the ratio fell from 5 to 1 in 1960 to just 2.8 to 1 in 2012. This did not prevent large improvements in living standards for both workers and retirees. It is hard to see why a comparable drop in the next 50 years in the European Union would lead to serious disruptions. (Actually it is surprising that the ratio of workers to retirees is so much higher in Europe than the United States since the EU does have an older population.)

Simple arithmetic shows that the impact of productivity growth will swamp the impact of demographics. If a retiree gets 80 percent of the income of an average worker, then it is necessary to have a tax rate (or its equivalent) of just under 17 percent on workers when the ratio of workers to retiree is 4 to 1. The necessary tax rate would be a bit less than 29 percent if the ratio is just 2 to 1.

If the country is able to maintain just a 1.5 percent rate of productivity growth over this 50 year period (the pace of growth during the slowdown period in the United States) and wages keep pace with productivity growth, then before tax wages will be 110 percent higher in 2062 than they are today. This would leave after-tax wages more than 80 percent higher than today. It’s difficult to see why Europeans should be viewing this as a crisis.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión