Everyone knows the story about the two old men in a retirement home. The first one complains that, “the food here is poison.” His friend agrees with him then adds, “and the portions are so small.”

We have been getting this story the last several years in assessments of the labor market. The economy remains far below full employment by every measure. The employment to population ratio is still more than 4 percentage points below its pre-recession level. We are almost 9 million jobs below trend levels. In addition, many have pointed out that a disproportionate number of the jobs that have been created have been low-paying jobs in sectors like hotels and restaurants.

Some analysts have picked up on the latter point to argue there has been a fundamental change in the economy. They claim we are moving to an economy that produces high-paying jobs for highly skilled people (e.g. doctors, lawyers, financial engineers) and bad jobs for everyone else. I have beaten up on this one elsewhere. (The trick for doctors and lawyers is protectionism not skills.)

However there is no dispute that bad jobs seem to be growing rapidly as a share of employment at present. The question is why. An alternative explanation to the “it just happens” view is that the weak economy itself is responsible for the proliferation of bad jobs. In other words, because the economy is not generating decent jobs in any reasonable number, workers are forced to take bad jobs. In that story the proliferation of bad jobs is the direct result of a weak economy.

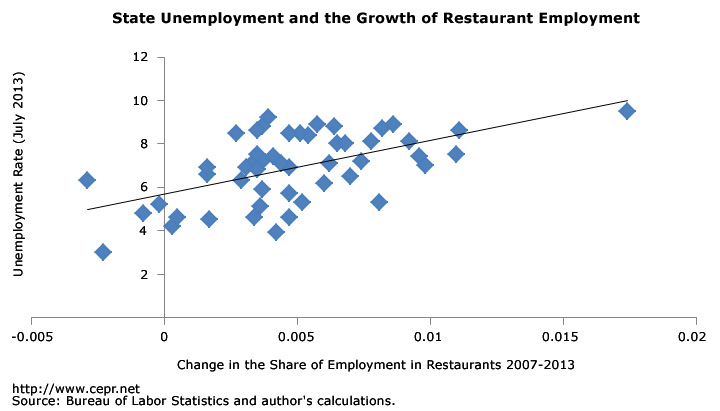

I did a very crude test of this story. I regressed the rise in the share of hotel and restuarant employment from 2007 to the first half of 2013, across states, against their unemployment rate in July of 2013. Here’s the picture.

While far from conclusive, this looks like pretty good support for the bad labor markets lead to bad jobs story. (For regression fans, the coefficient of the unemployment rate variable was 0.0013 with a t-statistic of 4.65, which is significant at the 1 percent level.) There are of course other reasons than the lack of good jobs that could cause the share of restaurant employment to grow more in states with high unemployment.

For example, if we believe that the rate of growth of restaurant employment is more or less fixed, then states with weak overall job growth would see a rising share of restaurant work. But the substatantial variation in the growth rate of restuarant employment across states would make this story less credible.

Anyhow, I wouldn’t claim this simple test seals the case, but it strongly suggest that the story of bad jobs is the story of weak labor markets. In this story the food is poison because the portions are small.

Everyone knows the story about the two old men in a retirement home. The first one complains that, “the food here is poison.” His friend agrees with him then adds, “and the portions are so small.”

We have been getting this story the last several years in assessments of the labor market. The economy remains far below full employment by every measure. The employment to population ratio is still more than 4 percentage points below its pre-recession level. We are almost 9 million jobs below trend levels. In addition, many have pointed out that a disproportionate number of the jobs that have been created have been low-paying jobs in sectors like hotels and restaurants.

Some analysts have picked up on the latter point to argue there has been a fundamental change in the economy. They claim we are moving to an economy that produces high-paying jobs for highly skilled people (e.g. doctors, lawyers, financial engineers) and bad jobs for everyone else. I have beaten up on this one elsewhere. (The trick for doctors and lawyers is protectionism not skills.)

However there is no dispute that bad jobs seem to be growing rapidly as a share of employment at present. The question is why. An alternative explanation to the “it just happens” view is that the weak economy itself is responsible for the proliferation of bad jobs. In other words, because the economy is not generating decent jobs in any reasonable number, workers are forced to take bad jobs. In that story the proliferation of bad jobs is the direct result of a weak economy.

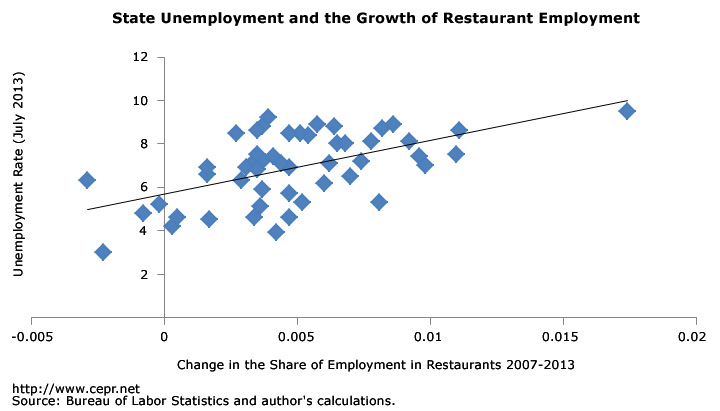

I did a very crude test of this story. I regressed the rise in the share of hotel and restuarant employment from 2007 to the first half of 2013, across states, against their unemployment rate in July of 2013. Here’s the picture.

While far from conclusive, this looks like pretty good support for the bad labor markets lead to bad jobs story. (For regression fans, the coefficient of the unemployment rate variable was 0.0013 with a t-statistic of 4.65, which is significant at the 1 percent level.) There are of course other reasons than the lack of good jobs that could cause the share of restaurant employment to grow more in states with high unemployment.

For example, if we believe that the rate of growth of restaurant employment is more or less fixed, then states with weak overall job growth would see a rising share of restaurant work. But the substatantial variation in the growth rate of restuarant employment across states would make this story less credible.

Anyhow, I wouldn’t claim this simple test seals the case, but it strongly suggest that the story of bad jobs is the story of weak labor markets. In this story the food is poison because the portions are small.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

C Fred Bergsten suggests that Obama could get some lessons from Sweden when he visits there next week. His piece emphasizes the market orientation of Sweden’s government. While the country has definitely rolled back some of its social welfare state over the last quarter century, readers could be misled by some of the items in Bergsten’s column.

For example, Bergsten tells readers:

“Swedish social security became a true insurance system, rather than a pay-as-you-go one with huge unfunded liabilities as in the United States.”

The defined benefit portion of Sweden’s reformed Social Security system is supported by a tax that is roughly 30 percent higher than the U.S. tax. (Okay, I was doing a Peter Peterson imitation.The tax rate is roughly one-third higher, but by saying “30 percent” I can get many readers to think I mean 30 percentage points.) Anyhow, even post-reform Sweden’s Social Security system is substantially more generous than the U.S. system.

It is also important to note that nearly 90 percent of Swedish workers are covered by a union contract. Unions continue to be a major force in Swedish politics which all political parties recognize.

The piece also reports that Sweden’s per capita income had fallen from one of the highest in the world in 1970 to 17th by the late 1980s. While it portrays this as a fall attributable to its over-reaching welfare state, the story is a bit more complicated.

According to the OECD, average annual hours worked fell by more than 10 percent from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. This suggests that Swedes were taking much of the benefit of productivity growth in leisure rather than income. There is no economic reason to object to workers making this choice even though it lowers per capita income.

The other factor to consider is that Sweden has a substantial grey market economy, with people doing work off the books to avoid taxes and regulations. (For example, people might paint houses and do car repairs without reporting their income.) Some conservatives economists have estimated the size of this economy as being as large one-third of Sweden’s official GDP. While such an estimate is almost certainly exaggerated, there is no doubt that the country has a larger grey market than some countries with lower tax rates.

This grey market does not get counted in GDP. Any effort to fully measure economic activity in Sweden would include these services. If the grey market is anywhere near as large as conservatives claim, then Sweden’s per capita income would still rank near the top in the world.

C Fred Bergsten suggests that Obama could get some lessons from Sweden when he visits there next week. His piece emphasizes the market orientation of Sweden’s government. While the country has definitely rolled back some of its social welfare state over the last quarter century, readers could be misled by some of the items in Bergsten’s column.

For example, Bergsten tells readers:

“Swedish social security became a true insurance system, rather than a pay-as-you-go one with huge unfunded liabilities as in the United States.”

The defined benefit portion of Sweden’s reformed Social Security system is supported by a tax that is roughly 30 percent higher than the U.S. tax. (Okay, I was doing a Peter Peterson imitation.The tax rate is roughly one-third higher, but by saying “30 percent” I can get many readers to think I mean 30 percentage points.) Anyhow, even post-reform Sweden’s Social Security system is substantially more generous than the U.S. system.

It is also important to note that nearly 90 percent of Swedish workers are covered by a union contract. Unions continue to be a major force in Swedish politics which all political parties recognize.

The piece also reports that Sweden’s per capita income had fallen from one of the highest in the world in 1970 to 17th by the late 1980s. While it portrays this as a fall attributable to its over-reaching welfare state, the story is a bit more complicated.

According to the OECD, average annual hours worked fell by more than 10 percent from the late 1960s to the early 1980s. This suggests that Swedes were taking much of the benefit of productivity growth in leisure rather than income. There is no economic reason to object to workers making this choice even though it lowers per capita income.

The other factor to consider is that Sweden has a substantial grey market economy, with people doing work off the books to avoid taxes and regulations. (For example, people might paint houses and do car repairs without reporting their income.) Some conservatives economists have estimated the size of this economy as being as large one-third of Sweden’s official GDP. While such an estimate is almost certainly exaggerated, there is no doubt that the country has a larger grey market than some countries with lower tax rates.

This grey market does not get counted in GDP. Any effort to fully measure economic activity in Sweden would include these services. If the grey market is anywhere near as large as conservatives claim, then Sweden’s per capita income would still rank near the top in the world.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Commerce Department release of revised data showing that GDP grew by more than originally reported in the second quarter was generally reported as very positive news. This is striking since the growth rate was only 2.5 percent. (One fifth of this growth was due to more rapid inventory accumulation.)

Most economists estimate the economy’s trend growth rate as 2.2 percent to 2.4 percent. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the economy is currently operating at almost 6 percentage points below its potential. This means that at the second quarter growth rate it will take between 20 and 60 years to get back to potential GDP.

The Commerce Department release of revised data showing that GDP grew by more than originally reported in the second quarter was generally reported as very positive news. This is striking since the growth rate was only 2.5 percent. (One fifth of this growth was due to more rapid inventory accumulation.)

Most economists estimate the economy’s trend growth rate as 2.2 percent to 2.4 percent. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the economy is currently operating at almost 6 percentage points below its potential. This means that at the second quarter growth rate it will take between 20 and 60 years to get back to potential GDP.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A homeowner down the street from me left his dog outside all day in the mid-summer heat. The dog died. Is this supposed to mean that homeowners are irresponsible people who can’t be trusted to keep up a neighborhood and use basic common sense? Apparently in the pages of the NYT it does.

The NYT devoted a whole article to complaints that renters who have moved in to homes that were formerly occupied by owner occupants were bringing down the quality of neighborhoods. The piece is full of anecdotes, including one about a dog being tied to a post in the hot summer sun by a renter.

Many of the comments are absurd on their face. For example, the article has a quote from one complaining homeowner:

“Who’s going to paint the outside of a rental house? You’d almost have to be crazy.”

The obvious answer to the question is the landlord. She should want to paint the outside of a rental house since her property will lose value if it is not properly protected from the elements. There are certainly many landlords who do not properly maintain properties, but there are also many homeowners who don’t properly maintain properties.

The underlying story missed in this article is that the neighborhoods being discussed have become less desirable. That is why house prices have fallen sharply.The renters who are moving in are likely to have lower incomes and less stable jobs than their neighbors. However if the homes were not rented, then they would either sit vacant, or eventually be sold to homeowners with lower incomes and less stable jobs than their neighbors. The piece wrongly implies that the problem is that the people moving in are renters. (Btw, the story about the dog dying in the heat is unfortunately true.)

A homeowner down the street from me left his dog outside all day in the mid-summer heat. The dog died. Is this supposed to mean that homeowners are irresponsible people who can’t be trusted to keep up a neighborhood and use basic common sense? Apparently in the pages of the NYT it does.

The NYT devoted a whole article to complaints that renters who have moved in to homes that were formerly occupied by owner occupants were bringing down the quality of neighborhoods. The piece is full of anecdotes, including one about a dog being tied to a post in the hot summer sun by a renter.

Many of the comments are absurd on their face. For example, the article has a quote from one complaining homeowner:

“Who’s going to paint the outside of a rental house? You’d almost have to be crazy.”

The obvious answer to the question is the landlord. She should want to paint the outside of a rental house since her property will lose value if it is not properly protected from the elements. There are certainly many landlords who do not properly maintain properties, but there are also many homeowners who don’t properly maintain properties.

The underlying story missed in this article is that the neighborhoods being discussed have become less desirable. That is why house prices have fallen sharply.The renters who are moving in are likely to have lower incomes and less stable jobs than their neighbors. However if the homes were not rented, then they would either sit vacant, or eventually be sold to homeowners with lower incomes and less stable jobs than their neighbors. The piece wrongly implies that the problem is that the people moving in are renters. (Btw, the story about the dog dying in the heat is unfortunately true.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times had an article reporting on how the two largest dialysis clinics are lobbying to increase reimbursements from the government. The issue stems from a change in the way the government paid for an anemia drug.

The government had been paying per dosage of the drug. As economic theory predicts, the huge mark-up over the free market price provided by patent monopolies encouraged the massive overuse of the drug. The government swtiched to a flat fee per treatment, which led to a sharp cutback in the drug’s usage. The government is now proposing a cutback in reimbursements based on the fact that this drug is being used in much smaller doses. If the research had been funded in advance and the drug were produced and sold in a free market, this sort of problem never would have arisen.

At one point the article includes the bizarre statement:

“The multibillion-dollar dialysis industry has been accused by medical researchers and former employees of putting a higher priority on profits than on care before ….”

Wouldn’t any reasonable person assume that a corporation will always put profit as its top priority? That is pretty much what they claim to do, so this hardly qualifies as a “accusation.” It’s sort of like accusing a linebacker of tackling quarterbacks.

It is worth noting the amount of money the government pays for dialysis. The article puts it at $32.9 billion a year. (CEPR’s really cool budget calculator shows this to be just less than 1.0 percent of federal spending.) This amount is more than 40 percent of what the federal government spends on food stamps each year.

The New York Times had an article reporting on how the two largest dialysis clinics are lobbying to increase reimbursements from the government. The issue stems from a change in the way the government paid for an anemia drug.

The government had been paying per dosage of the drug. As economic theory predicts, the huge mark-up over the free market price provided by patent monopolies encouraged the massive overuse of the drug. The government swtiched to a flat fee per treatment, which led to a sharp cutback in the drug’s usage. The government is now proposing a cutback in reimbursements based on the fact that this drug is being used in much smaller doses. If the research had been funded in advance and the drug were produced and sold in a free market, this sort of problem never would have arisen.

At one point the article includes the bizarre statement:

“The multibillion-dollar dialysis industry has been accused by medical researchers and former employees of putting a higher priority on profits than on care before ….”

Wouldn’t any reasonable person assume that a corporation will always put profit as its top priority? That is pretty much what they claim to do, so this hardly qualifies as a “accusation.” It’s sort of like accusing a linebacker of tackling quarterbacks.

It is worth noting the amount of money the government pays for dialysis. The article puts it at $32.9 billion a year. (CEPR’s really cool budget calculator shows this to be just less than 1.0 percent of federal spending.) This amount is more than 40 percent of what the federal government spends on food stamps each year.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson wrote about the recent downturn in financial markets in several major developing countries in response to the rise in long-term interest rates in the United States. While he notes that this is not likely to lead to a larger crisis given the current circumstances in the developing world, he concludes his piece by telling readers:

“Every major financial crisis of the past 20 years has begun with some relatively minor event whose significance seemed isolated: weakness of the Thai baht in the summer of 1997; trouble in the market for “subprime” U.S. mortgages in 2007; Greece’s misreporting of its budget deficit in 2009. Could this be ‘deja vu all over again’?”

It is worth making an important distinction between these crises. The subprime mortgage market was a small part of a much larger story, a serious bubble in the U.S. housing market that was driving the economy. For some bizarre reason, the Fed and most other economists did not recognize this situation even as the bubble was already rapidly deflating. (Many do not understand it even today.) The Greek situation was a story of serious imbalances in the euro zone with the southern countries running massive current account deficits that could not be corrected because of the common currency.

By contrast, the East Asian situation was largely a case of a crisis of confidence that was aggravated into something much bigger through mismanagement by the I.M.F. and folks at Treasury like Larry Summers. The current situation looks much more like the East Asian situation.

There is no inherent problem with capital flowing from rich countries to the more rapidly growing developing countries, that is what the textbooks say is supposed to happen. The real problem will be if the I.M.F.-Summers mistakes of the past are repeated.

Robert Samuelson wrote about the recent downturn in financial markets in several major developing countries in response to the rise in long-term interest rates in the United States. While he notes that this is not likely to lead to a larger crisis given the current circumstances in the developing world, he concludes his piece by telling readers:

“Every major financial crisis of the past 20 years has begun with some relatively minor event whose significance seemed isolated: weakness of the Thai baht in the summer of 1997; trouble in the market for “subprime” U.S. mortgages in 2007; Greece’s misreporting of its budget deficit in 2009. Could this be ‘deja vu all over again’?”

It is worth making an important distinction between these crises. The subprime mortgage market was a small part of a much larger story, a serious bubble in the U.S. housing market that was driving the economy. For some bizarre reason, the Fed and most other economists did not recognize this situation even as the bubble was already rapidly deflating. (Many do not understand it even today.) The Greek situation was a story of serious imbalances in the euro zone with the southern countries running massive current account deficits that could not be corrected because of the common currency.

By contrast, the East Asian situation was largely a case of a crisis of confidence that was aggravated into something much bigger through mismanagement by the I.M.F. and folks at Treasury like Larry Summers. The current situation looks much more like the East Asian situation.

There is no inherent problem with capital flowing from rich countries to the more rapidly growing developing countries, that is what the textbooks say is supposed to happen. The real problem will be if the I.M.F.-Summers mistakes of the past are repeated.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT story on how demographic change seems to be helping Democrats in Virginia noted as an offsetting factor that mining areas are increasingly Republican. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Virginia has 10.700 people employed in mining and logging. This is less than 0.3 percent of the state’s labor force. It is unlikely that this group will have much impact on the outcome of 2013 election.

A NYT story on how demographic change seems to be helping Democrats in Virginia noted as an offsetting factor that mining areas are increasingly Republican. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Virginia has 10.700 people employed in mining and logging. This is less than 0.3 percent of the state’s labor force. It is unlikely that this group will have much impact on the outcome of 2013 election.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post seems to have made it a goal to get everything possible about the housing market wrong. Its article today on the Case-Shiller June price index attributed the slower price growth in part to higher interest rates. This makes no sense.

The Case-Shiller index is an average of three months data. The June release is based on the price of houses that were closed in April, May, and June. Since there is typically 6-8 weeks between when a contract is signed and when a sale is completed these houses would have come under contract in the period from February to May. This is a period before there was any real rise in interest rates.

Interest rates first exceeded their winter levels at the end of May and then increased more in June and July. We will first begin to see a limited impact of higher interest rates in the Case Shilller index in the July data and the impact of the rise will not be fully apparent until the October index is released.

The Washington Post seems to have made it a goal to get everything possible about the housing market wrong. Its article today on the Case-Shiller June price index attributed the slower price growth in part to higher interest rates. This makes no sense.

The Case-Shiller index is an average of three months data. The June release is based on the price of houses that were closed in April, May, and June. Since there is typically 6-8 weeks between when a contract is signed and when a sale is completed these houses would have come under contract in the period from February to May. This is a period before there was any real rise in interest rates.

Interest rates first exceeded their winter levels at the end of May and then increased more in June and July. We will first begin to see a limited impact of higher interest rates in the Case Shilller index in the July data and the impact of the rise will not be fully apparent until the October index is released.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That was the missing sentence in a Washington Post article on the battle over the debt ceiling. The article referred to the 2011 battle that brought the country within days of hitting the legal limit on borrowing. It told readers:

“Many economists say that episode led to uncertainty that harmed the economy.”

It’s hard to find evidence for this assertion in the data. The economy grew at a 2.3 percent annual rate in the second and third quarters of 2011, the period most immediately affected by the crisis. This is slightly higher than its 1.9 percent rate over the last three years. Non-residential investment, the category of spending that might be most responsive to such fears, rose at a 13.3 percent annual rate over these two quarters.

There also was no evidence of a lasting effect on the credibility of the government as a debtor. The interest rate on Treasury bonds plummeted following the crisis (they should have risen if people were fearful), although this was primarily due to the euro-zone crisis. When investors became fearful about the future of the euro they turned to Treasury bonds as a safe alternative.

That was the missing sentence in a Washington Post article on the battle over the debt ceiling. The article referred to the 2011 battle that brought the country within days of hitting the legal limit on borrowing. It told readers:

“Many economists say that episode led to uncertainty that harmed the economy.”

It’s hard to find evidence for this assertion in the data. The economy grew at a 2.3 percent annual rate in the second and third quarters of 2011, the period most immediately affected by the crisis. This is slightly higher than its 1.9 percent rate over the last three years. Non-residential investment, the category of spending that might be most responsive to such fears, rose at a 13.3 percent annual rate over these two quarters.

There also was no evidence of a lasting effect on the credibility of the government as a debtor. The interest rate on Treasury bonds plummeted following the crisis (they should have risen if people were fearful), although this was primarily due to the euro-zone crisis. When investors became fearful about the future of the euro they turned to Treasury bonds as a safe alternative.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión