George Will is apparently still obsessed with inflation and very disappointed that the Fed’s policy of quantitative easing has not led to hyperinflation thus far. This led him to write a seriously confused column condemning the Fed and its Chairman Ben Bernanke.

Will complains:

“A touch on the tiller here, a nimble reversal there — these express the fatal conceit of an institution that considers itself capable of, and responsible for, fine-tuning the nation’s $15.7 trillion economy.”

This assertion is incredibly wide of the mark, even getting the size of the economy wrong by $1 trillion. Certainly Bernanke and the Fed are not claiming the ability to fine-tune the economy. If they had this ability then the economy would not currently be operating at a level of output that is $1 trillion below its potential. That is not anywhere in the ballpark of fine-tuning.

The comment that apparently upset Will is Bernanke’s claim that the Fed would have no problem raising interest rates and slowing the economy if there was an outbreak of inflation on the horizon. It’s not clear why this comment would seem so strange. Inflation only rises very gradually and there has been no problem of inflation growing out of control for more than three decades in the United States or any other wealthy country. This would suggest that Bernanke has some reason for believing that he or his successor will continue to be able to prevent an outbreak of accelerating inflation.

Will is also convinced that the stock market has been artificially inflated by the Fed’s quantitative easing and zero interest rate policy. The S&P 500 peaked at over 1550 in the fall of 2007. If it had risen in step with the trend growth rate of GDP it would be over 1950 today, almost 20 percent higher than its current level. For some reason Will never complained about the 2007 stock market level in spite of the fact that it was markedly higher relative to the value of GDP at the time.

Note — typo corrected in first sentence.

George Will is apparently still obsessed with inflation and very disappointed that the Fed’s policy of quantitative easing has not led to hyperinflation thus far. This led him to write a seriously confused column condemning the Fed and its Chairman Ben Bernanke.

Will complains:

“A touch on the tiller here, a nimble reversal there — these express the fatal conceit of an institution that considers itself capable of, and responsible for, fine-tuning the nation’s $15.7 trillion economy.”

This assertion is incredibly wide of the mark, even getting the size of the economy wrong by $1 trillion. Certainly Bernanke and the Fed are not claiming the ability to fine-tune the economy. If they had this ability then the economy would not currently be operating at a level of output that is $1 trillion below its potential. That is not anywhere in the ballpark of fine-tuning.

The comment that apparently upset Will is Bernanke’s claim that the Fed would have no problem raising interest rates and slowing the economy if there was an outbreak of inflation on the horizon. It’s not clear why this comment would seem so strange. Inflation only rises very gradually and there has been no problem of inflation growing out of control for more than three decades in the United States or any other wealthy country. This would suggest that Bernanke has some reason for believing that he or his successor will continue to be able to prevent an outbreak of accelerating inflation.

Will is also convinced that the stock market has been artificially inflated by the Fed’s quantitative easing and zero interest rate policy. The S&P 500 peaked at over 1550 in the fall of 2007. If it had risen in step with the trend growth rate of GDP it would be over 1950 today, almost 20 percent higher than its current level. For some reason Will never complained about the 2007 stock market level in spite of the fact that it was markedly higher relative to the value of GDP at the time.

Note — typo corrected in first sentence.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

No one expects serious budget or economic analysis on the Washington Post’s editorial page, but endorsing a tax and spending freeze until the unemployment rate falls below 6.5 percent (bizarrely called “Jobs First”) is an embarrassment even for the Post. Incredibly, neither the Post nor their “No Labels” leaders explain what a freeze even means. Is spending frozen in nominal terms, in real terms? Does it allow for increases in spending in mandatory programs like Social Security and Medicare?

You won’t find answers to these basic questions in either the Post’s editorial or on the No Labels website. (For those folks who aren’t familiar with them, No Labels was started by a bunch of Wall Street types who think that everyone should just stop fighting and agree with them.)

Anyhow, it is hard to comment much on something that is so vague, but the irony of the “Jobs First” label should be apparent to everyone. In order to get down to 6.5 percent unemployment in a reasonable period of time we are likely to need more government spending. By freezing government spending, the No Labels crew are effectively putting jobs last. But hey, this is the Washington Post editorial page, who cares about economics, logic, or jobs?

No one expects serious budget or economic analysis on the Washington Post’s editorial page, but endorsing a tax and spending freeze until the unemployment rate falls below 6.5 percent (bizarrely called “Jobs First”) is an embarrassment even for the Post. Incredibly, neither the Post nor their “No Labels” leaders explain what a freeze even means. Is spending frozen in nominal terms, in real terms? Does it allow for increases in spending in mandatory programs like Social Security and Medicare?

You won’t find answers to these basic questions in either the Post’s editorial or on the No Labels website. (For those folks who aren’t familiar with them, No Labels was started by a bunch of Wall Street types who think that everyone should just stop fighting and agree with them.)

Anyhow, it is hard to comment much on something that is so vague, but the irony of the “Jobs First” label should be apparent to everyone. In order to get down to 6.5 percent unemployment in a reasonable period of time we are likely to need more government spending. By freezing government spending, the No Labels crew are effectively putting jobs last. But hey, this is the Washington Post editorial page, who cares about economics, logic, or jobs?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s always good to see CEPR’s research findings picked up in the NYT even if someone else had to do them. In this case, the NYT reports that the Affordable Care Act is not leading to more part-time work. Yes, we showed that two months ago. But hey, the lag is getting much shorter. After all, we warned that the collapse of the housing bubble could lead to a severe recession and serious financial consequences back in 2002. They didn’t begin to take that one seriously until the collapse was already in progress.

It’s always good to see CEPR’s research findings picked up in the NYT even if someone else had to do them. In this case, the NYT reports that the Affordable Care Act is not leading to more part-time work. Yes, we showed that two months ago. But hey, the lag is getting much shorter. After all, we warned that the collapse of the housing bubble could lead to a severe recession and serious financial consequences back in 2002. They didn’t begin to take that one seriously until the collapse was already in progress.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

If you ever wondered where all the psychics came from who hang their shingles around DC, the answer is that they are probably former Washington Post reporters. The paper again told readers what people think. In an article on how the latest battle over Obamacare has re-energized the Tea Party, the Post told readers:

“Obamacare, which seeks to extend health coverage to millions of uninsured Americans, is viewed by tea party activists as a dangerous new government intrusion. They fear it will reduce their choices of medical providers and burden the weak economy.”

Of course the Post has no clue as to how tea party activists actually view Obamacare or what they fear. Many may fear that the government will send death panels into their homes to deny them or their loved ones care since this is what many of their leaders have asserted. A real newspaper would report on what people say and leave speculation about their fears and beliefs to others.

If you ever wondered where all the psychics came from who hang their shingles around DC, the answer is that they are probably former Washington Post reporters. The paper again told readers what people think. In an article on how the latest battle over Obamacare has re-energized the Tea Party, the Post told readers:

“Obamacare, which seeks to extend health coverage to millions of uninsured Americans, is viewed by tea party activists as a dangerous new government intrusion. They fear it will reduce their choices of medical providers and burden the weak economy.”

Of course the Post has no clue as to how tea party activists actually view Obamacare or what they fear. Many may fear that the government will send death panels into their homes to deny them or their loved ones care since this is what many of their leaders have asserted. A real newspaper would report on what people say and leave speculation about their fears and beliefs to others.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

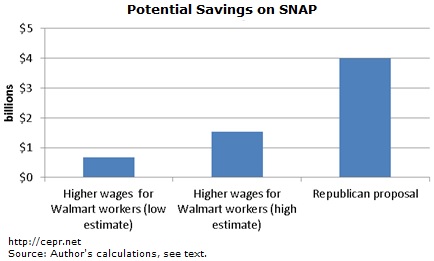

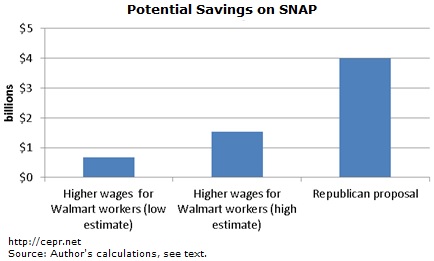

Last week I blamed the media in general and the New York Times in particular for the battle over the Republican proposal to cut food stamps. The logic is that the media routinely report that the Republicans want to cut $4 billion from the program. Undoubtedly many people hearing this number believe that it constitutes a major expense for the federal government.

The proposed cut to the program is actually equal to just 0.086 percent of federal spending. In other words, it could make a big difference to the people directly affected, but it makes almost no difference in terms of the overall budget. Very few people understand this fact because $4 billion sounds like a lot of money. The media could help to clear up this confusion by reporting the number as a share of the budget, but they don’t do that because — I don’t know.

Anyhow, for those who would like some further context for this proposed cut to the food stamp program we can consider the impact of raising wages on food stamp spending, specifically the wages of Walmart workers. The pay of many Walmart workers is not much above the minimum wage. As a result, a large percentage of Walmart workers qualify for government benefits like food stamps.

By contrast, if the wages of workers at the bottom end of the labor market had kept pace with productivity growth over the last 45 years it would be almost $17.00 an hour today. In that situation, very few Walmart workers would qualify for government benefits.

Earlier this year, the Democratic staff of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce put together calculations for the range of costs to the government through various programs of a Walmart superstore in Wisconsin that employs 300 workers. They put a range for the cost of food stamp benefits for a single store at between $96,000 and $219,500.

According to Fortune Magazine, Walmart has 2.1 million employees nationwide, which means that we should multiply these numbers by 7,000 to get a national total. That puts the annual cost of food stamps for the families of Walmart workers at between $670 million and $1.54 billion. The figure below shows the potential savings to taxpayers from raising the wages of Walmart workers to a level where they don’t qualify for food stamps with the savings from the Republicans’ proposed cuts to the program.

In short, if the goal is to save taxpayers money on food stamps there are different ways of achieving it. One is to cut benefits, as the Republicans have proposed. The other is to increase wages for low-paid workers so that they no longer qualify for benefits like food stamps.

Last week I blamed the media in general and the New York Times in particular for the battle over the Republican proposal to cut food stamps. The logic is that the media routinely report that the Republicans want to cut $4 billion from the program. Undoubtedly many people hearing this number believe that it constitutes a major expense for the federal government.

The proposed cut to the program is actually equal to just 0.086 percent of federal spending. In other words, it could make a big difference to the people directly affected, but it makes almost no difference in terms of the overall budget. Very few people understand this fact because $4 billion sounds like a lot of money. The media could help to clear up this confusion by reporting the number as a share of the budget, but they don’t do that because — I don’t know.

Anyhow, for those who would like some further context for this proposed cut to the food stamp program we can consider the impact of raising wages on food stamp spending, specifically the wages of Walmart workers. The pay of many Walmart workers is not much above the minimum wage. As a result, a large percentage of Walmart workers qualify for government benefits like food stamps.

By contrast, if the wages of workers at the bottom end of the labor market had kept pace with productivity growth over the last 45 years it would be almost $17.00 an hour today. In that situation, very few Walmart workers would qualify for government benefits.

Earlier this year, the Democratic staff of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce put together calculations for the range of costs to the government through various programs of a Walmart superstore in Wisconsin that employs 300 workers. They put a range for the cost of food stamp benefits for a single store at between $96,000 and $219,500.

According to Fortune Magazine, Walmart has 2.1 million employees nationwide, which means that we should multiply these numbers by 7,000 to get a national total. That puts the annual cost of food stamps for the families of Walmart workers at between $670 million and $1.54 billion. The figure below shows the potential savings to taxpayers from raising the wages of Walmart workers to a level where they don’t qualify for food stamps with the savings from the Republicans’ proposed cuts to the program.

In short, if the goal is to save taxpayers money on food stamps there are different ways of achieving it. One is to cut benefits, as the Republicans have proposed. The other is to increase wages for low-paid workers so that they no longer qualify for benefits like food stamps.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We all should be thankful for the vigilance of the Washington Post, otherwise we might not know about an agency in Alaska that could be wasting around $1.8 million a year in federal spending. The Post decided to do a major story on the inspector general of a small development agency in Alaska who wrote a letter to Congress saying that the agency was a waste of money and should be closed.

According to the piece, the agency, the Denali Commission, was the creation of former Alaska Senator Ted Stevens. At one time more than $150 million was flowing through it to finance various projects in Alaska. This flow has been reduced to $10.6 million following Senator Steven’s defeat and subsequent death.

The immediate issue according to the inspector general is not the $10.6 million in projects, many or all of which may be worthwhile, but rather the agency itself. The inspector general complained that it was an unnecessary intermediary for these funds and therefore a waste of taxpayer dollars.

The article indicates that the agency has 12 employees. If we assume that total compensation for each, plus the indirect costs associated with running the office, come to $150,000 a year, then the implied waste would be $1.8 million a year, assuming that no equivalent supervisory structure would need to be established elsewhere in Alaska’s government.

If we go to CEPR’s incredibly spiffy budget calculator, we see that this spending qualifies as less than 0.0001 percent of the budget. Clearly this article was a good use of a Post’s reporter’s time and way to consume a large chunk of space in the newspaper.

We all should be thankful for the vigilance of the Washington Post, otherwise we might not know about an agency in Alaska that could be wasting around $1.8 million a year in federal spending. The Post decided to do a major story on the inspector general of a small development agency in Alaska who wrote a letter to Congress saying that the agency was a waste of money and should be closed.

According to the piece, the agency, the Denali Commission, was the creation of former Alaska Senator Ted Stevens. At one time more than $150 million was flowing through it to finance various projects in Alaska. This flow has been reduced to $10.6 million following Senator Steven’s defeat and subsequent death.

The immediate issue according to the inspector general is not the $10.6 million in projects, many or all of which may be worthwhile, but rather the agency itself. The inspector general complained that it was an unnecessary intermediary for these funds and therefore a waste of taxpayer dollars.

The article indicates that the agency has 12 employees. If we assume that total compensation for each, plus the indirect costs associated with running the office, come to $150,000 a year, then the implied waste would be $1.8 million a year, assuming that no equivalent supervisory structure would need to be established elsewhere in Alaska’s government.

If we go to CEPR’s incredibly spiffy budget calculator, we see that this spending qualifies as less than 0.0001 percent of the budget. Clearly this article was a good use of a Post’s reporter’s time and way to consume a large chunk of space in the newspaper.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT Room for Debate section must have caught many readers by surprise on Thursday when it posed the question of whether economic growth was essential for mobility and it held Mexico up as an example of a dynamic economy. The reason this might have been a surprise is that Mexico has mostly been a growth laggard. It’s growth rate has generally been considerably slower than the growth rate of other Latin American countries and is projected to remain slower in the foreseeable future.

The NYT Room for Debate section must have caught many readers by surprise on Thursday when it posed the question of whether economic growth was essential for mobility and it held Mexico up as an example of a dynamic economy. The reason this might have been a surprise is that Mexico has mostly been a growth laggard. It’s growth rate has generally been considerably slower than the growth rate of other Latin American countries and is projected to remain slower in the foreseeable future.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post ran an article highlighting new calculations of city pension liabilities from Moody’s, the bond rating agency. Moody’s is probably best known to most people for rating hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of subprime mortgage backed securities as investment grade during the housing bubble years. It received tens of millions of dollars in fees for these ratings from the investment banks that issued these securities.

The new pension liability figures are obtained by using a discount rate for pension liabilities that is considerably lower than the expected rate of return on pension assets. This methodology increases pension liabilities by around 50 percent compared with the traditional method.

If a pension fund was fully funded according to the new Moody’s methodology, but continued to invest in a mix of assets that gave a much higher rate of return than the discount rate used for calculating liabilities, then it would have effectively overfunded its pension. That would mean taxing current taxpayers more than necessary in order to allow future taxpayers to pay substantially less in taxes to finance public services. Usually economists believe that each generation should pay taxes that are roughly proportional to the services they receive. Moody’s methodology would not lead to this result if it became the basis for pension funding decisions.

It would have been worth highlighting this point about the Moody’s methodology. Most readers are unlikely to be aware of the strange policy implications of following the methodology and thereby assume that governments would be wrong not to accept it.

It is worth noting that public pensions did grossly exaggerate the expected returns on their assets in the stock bubble years of the late 1990s and at the market peaks hit in the last decade. Unfortunately, unlike some of us, Moody’s did not point this problem out at the time. One result was that many state and local governments raised their pensions and made additional payouts to workers which would not have been justified if they had used a discount rate that was consistent with the expected return on their assets.

The Washington Post ran an article highlighting new calculations of city pension liabilities from Moody’s, the bond rating agency. Moody’s is probably best known to most people for rating hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of subprime mortgage backed securities as investment grade during the housing bubble years. It received tens of millions of dollars in fees for these ratings from the investment banks that issued these securities.

The new pension liability figures are obtained by using a discount rate for pension liabilities that is considerably lower than the expected rate of return on pension assets. This methodology increases pension liabilities by around 50 percent compared with the traditional method.

If a pension fund was fully funded according to the new Moody’s methodology, but continued to invest in a mix of assets that gave a much higher rate of return than the discount rate used for calculating liabilities, then it would have effectively overfunded its pension. That would mean taxing current taxpayers more than necessary in order to allow future taxpayers to pay substantially less in taxes to finance public services. Usually economists believe that each generation should pay taxes that are roughly proportional to the services they receive. Moody’s methodology would not lead to this result if it became the basis for pension funding decisions.

It would have been worth highlighting this point about the Moody’s methodology. Most readers are unlikely to be aware of the strange policy implications of following the methodology and thereby assume that governments would be wrong not to accept it.

It is worth noting that public pensions did grossly exaggerate the expected returns on their assets in the stock bubble years of the late 1990s and at the market peaks hit in the last decade. Unfortunately, unlike some of us, Moody’s did not point this problem out at the time. One result was that many state and local governments raised their pensions and made additional payouts to workers which would not have been justified if they had used a discount rate that was consistent with the expected return on their assets.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

You know times are bad when people start making a big deal about finding pennies in the street. That seems to be the case these days at the European Central Bank.

According to the New York Times, Joerg Asmussen, an Executive Board member of the European Central Bank, touted the growth potential of a trade agreement between the European Union and the United States. A study by the Centre for Economic and Policy Research in the United Kingdom (no connection to CEPR) found that in a best case scenario a deal would increase GDP in the United States by 0.39 percentage points when the impact is fully felt in 2027 (Table 16). In their more likely middle scenario, the gains to the United States would be 0.21 percent. That would translate into an increase in the annual growth rate of 0.015 percentage points.

While the gains for Europe might be slightly higher, it is worth noting that this projection does not take account of ways that a deal could slow growth, for example by increasing protections for intellectual property and putting in place investment rules that increase economic rents. It reveals a great deal about current economic prospects that a top policy official in the European Union would be touting such small potential benefits to growth.

You know times are bad when people start making a big deal about finding pennies in the street. That seems to be the case these days at the European Central Bank.

According to the New York Times, Joerg Asmussen, an Executive Board member of the European Central Bank, touted the growth potential of a trade agreement between the European Union and the United States. A study by the Centre for Economic and Policy Research in the United Kingdom (no connection to CEPR) found that in a best case scenario a deal would increase GDP in the United States by 0.39 percentage points when the impact is fully felt in 2027 (Table 16). In their more likely middle scenario, the gains to the United States would be 0.21 percent. That would translate into an increase in the annual growth rate of 0.015 percentage points.

While the gains for Europe might be slightly higher, it is worth noting that this projection does not take account of ways that a deal could slow growth, for example by increasing protections for intellectual property and putting in place investment rules that increase economic rents. It reveals a great deal about current economic prospects that a top policy official in the European Union would be touting such small potential benefits to growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión