With the Fed promising to keep the overnight money rate at zero long into the future, while it throws $85 billion a month into the economy with its quantitative easing policy, many are no doubt wondering who is on watch against another outbreak of inflation.

Greg Mankiw gave us the answer to that question in his NYT column today. After noting that the job vacancy had risen to 2.8 percent, which Mankiw describes as “almost back to normal,” he tells readers;

“Data on wage inflation also suggest that the labor market has firmed up. Over the past year, average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees grew 2.2 percent, compared with 1.3 percent in the previous 12 months. Accelerating wage growth is not the sign of a deeply depressed labor market.”

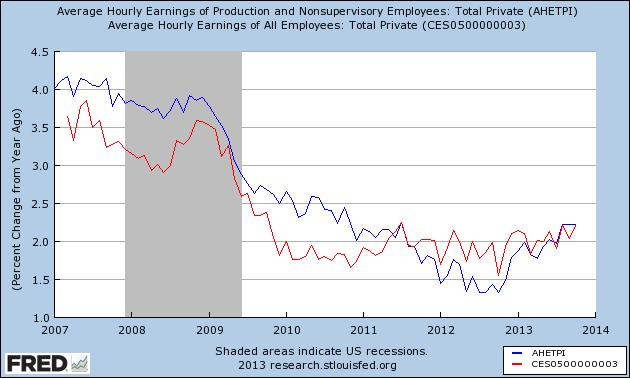

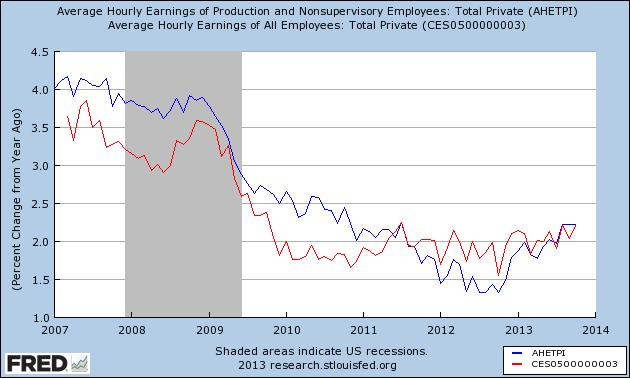

Let’s check this one out a bit more closely. The graph below shows the year over year growth in average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers (blue line) and all employees (red line). The former group comprises a bit more than 80 percent of the work force. The latter group tends to be more highly educated and is better paid on average.

If we look at the chart there is a modest acceleration in wage growth for production non-supervisory workers in 2013, but only because the rate of wage growth had continued to fall through 2012. If acceleration or deceleration is the measure of whether we have a fully utilized labor market we went quite quickly from a period of excess slack in 2012 when wages were falling to a period of tightness in the last year, even though employment growth has been rather tepid. That one seems a bit hard to accept.

Furthermore, if we use the broader measure of wage growth for all workers, we don’t see any evidence of acceleration at all. Wage growth has been hovering around 2.0 percent for the last two and a half years. It had been somewhat lower in 2010 (@ 1.6 percent), but there certainly is no upward pattern in this series.

A small upward tick in wage growth for production and non-supervisory workers, but no change in overall wage growth, is evidence of a shift in relative demand not excess aggregate demand. It would suggest that the demand for workers with more education and skills is weakening relative to the demand for less educated workers. Of course the difference is relatively modest and could easily be reversed in the months ahead, but that is how economists would ordinarily read this evidence. (It is also important to remember that with inflation running just a bit under 2.0 percent, this translates into an annual rate real wage growth of only around half a percentage point.)

It is also worth noting that Mankiw’s other measure of a fully employed labor force is also dubious. At 2.8 percent the vacancy rate is up from its low in 2010, but this is a series that does not move much. There were two months in 2012 where the vacancy rate was 2.8 percent also. In the 2001 downturn, the rate never fell below 2.3 percent. (It had been as high as 3.8 percent before the recession.) In contrast to the rise in the vacancy rate back to near pre-recession levels, the number of people looking for work is more than 50 percent higher than before the recession. That is hardly consistent with a story with the labor market being near full employment.

With the Fed promising to keep the overnight money rate at zero long into the future, while it throws $85 billion a month into the economy with its quantitative easing policy, many are no doubt wondering who is on watch against another outbreak of inflation.

Greg Mankiw gave us the answer to that question in his NYT column today. After noting that the job vacancy had risen to 2.8 percent, which Mankiw describes as “almost back to normal,” he tells readers;

“Data on wage inflation also suggest that the labor market has firmed up. Over the past year, average hourly earnings of production and nonsupervisory employees grew 2.2 percent, compared with 1.3 percent in the previous 12 months. Accelerating wage growth is not the sign of a deeply depressed labor market.”

Let’s check this one out a bit more closely. The graph below shows the year over year growth in average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers (blue line) and all employees (red line). The former group comprises a bit more than 80 percent of the work force. The latter group tends to be more highly educated and is better paid on average.

If we look at the chart there is a modest acceleration in wage growth for production non-supervisory workers in 2013, but only because the rate of wage growth had continued to fall through 2012. If acceleration or deceleration is the measure of whether we have a fully utilized labor market we went quite quickly from a period of excess slack in 2012 when wages were falling to a period of tightness in the last year, even though employment growth has been rather tepid. That one seems a bit hard to accept.

Furthermore, if we use the broader measure of wage growth for all workers, we don’t see any evidence of acceleration at all. Wage growth has been hovering around 2.0 percent for the last two and a half years. It had been somewhat lower in 2010 (@ 1.6 percent), but there certainly is no upward pattern in this series.

A small upward tick in wage growth for production and non-supervisory workers, but no change in overall wage growth, is evidence of a shift in relative demand not excess aggregate demand. It would suggest that the demand for workers with more education and skills is weakening relative to the demand for less educated workers. Of course the difference is relatively modest and could easily be reversed in the months ahead, but that is how economists would ordinarily read this evidence. (It is also important to remember that with inflation running just a bit under 2.0 percent, this translates into an annual rate real wage growth of only around half a percentage point.)

It is also worth noting that Mankiw’s other measure of a fully employed labor force is also dubious. At 2.8 percent the vacancy rate is up from its low in 2010, but this is a series that does not move much. There were two months in 2012 where the vacancy rate was 2.8 percent also. In the 2001 downturn, the rate never fell below 2.3 percent. (It had been as high as 3.8 percent before the recession.) In contrast to the rise in the vacancy rate back to near pre-recession levels, the number of people looking for work is more than 50 percent higher than before the recession. That is hardly consistent with a story with the labor market being near full employment.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It might have been worth including this piece of information in a NYT piece on a new set of regulations that Wyoming is imposing on fracking. The piece notes that companies engaged in fracking are not required to disclose the mix of chemicals they use in the process in order to avoid giving away secrets to competitors.

This is precisely the reason that we have patents. If a company has an especially innovative mix of chemicals they would be able to get it patented and prevent their competitors from using it for 20 years. The fact that companies can obtain patent protection makes it implausible that protecting secrets is the real motive for their refusal to disclose the chemicals they are using.

It might have been worth including this piece of information in a NYT piece on a new set of regulations that Wyoming is imposing on fracking. The piece notes that companies engaged in fracking are not required to disclose the mix of chemicals they use in the process in order to avoid giving away secrets to competitors.

This is precisely the reason that we have patents. If a company has an especially innovative mix of chemicals they would be able to get it patented and prevent their competitors from using it for 20 years. The fact that companies can obtain patent protection makes it implausible that protecting secrets is the real motive for their refusal to disclose the chemicals they are using.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Actually he is not upset by this fact, but he would be if he applied the logic in his column consistently. The column makes a point of highlighting how large transfers are to the elderly relative to transfers paid out to the young (e.g. food stamps and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families). Transfers to the elderly are large, but there is a good reason for this fact. People paid for their Social Security and Medicare benefits in their working years.

Samuelson wants us to ignore the fact that workers paid taxes that were designated for this purpose. That would be fair if he also thought that we should look at the billions of dollars in interest paid out on government bonds to rich people like Peter Peterson without taking account of the fact that Peterson and his billionaire friends paid for these bonds. That would be perverse but at least consistent.

As a practical matter, people pay somewhat more in Social Security taxes on average than they get back in benefits. They do get more back from Medicare than what they pay in taxes, but this is primarily because the United States pays so much more for health care than other wealthy countries. If the United States paid the same amount per person for its health care as other wealthy countries then Medicare taxes would roughly cover the cost of Medicare benefits. So this isn’t a story of the government being too generous to seniors, it’s a story of the government being too generous to doctors, drug companies, medical supply companies and others in the health care industry.

Samuelson is also badly confused when he tells readers:

“If lobbyists aim to empower the rich, they’re doing a lousy job. Democracy responds more to the mass of voters and to political crusades than to the wealthy or business interests. In the recent government shutdown, corporate America discovered that its influence on congressional Republicans was modest or nonexistent. It’s not that big companies and wealthy individuals are powerless, but their power is vastly exaggerated.

“The idea that government is routinely bought and sold by the rich is a source of widespread — but misleading — cynicism.”

Samuelson’s assertion is based on the fact that the rich don’t get many direct handouts from the government. But this is not what their lobbyists are trying to get. Instead they work to rig markets so that income will flow to their clients. This is easy to show in a large number of industries.

For example, the lobbyists have gotten drug companies patent monopolies that allow them to charge around $270 billion a year (@ 1.7 percent of GDP or 7.8 percent of the federal budget) more for their drugs than the free market price. They are currently drafting a trade deal, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, that will extend these monopolies in our trading partners thereby allowing the drug companies to charge higher prices overseas.

The financial industry has been able to arrange for too big to fail insurance that is equivalent to an annual subsidy of $80 billion a year (@ 0.5 percent of GDP or 2.0 percent of the federal budget). They are also likely to get a system under which Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will be replaced by private banks issuing mortgages with a government guarantee. This is likely to mean tens of billions of dollars in fees each year for the banks involved.

There are many other ways in which lobbyists use their power to get the government to structure markets so that the rich get richer. Samuelson is right that this is mostly not done through direct government payouts, but that is ignoring what the lobbyists are doing. (For more information read the good book on the topic.)

Actually he is not upset by this fact, but he would be if he applied the logic in his column consistently. The column makes a point of highlighting how large transfers are to the elderly relative to transfers paid out to the young (e.g. food stamps and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families). Transfers to the elderly are large, but there is a good reason for this fact. People paid for their Social Security and Medicare benefits in their working years.

Samuelson wants us to ignore the fact that workers paid taxes that were designated for this purpose. That would be fair if he also thought that we should look at the billions of dollars in interest paid out on government bonds to rich people like Peter Peterson without taking account of the fact that Peterson and his billionaire friends paid for these bonds. That would be perverse but at least consistent.

As a practical matter, people pay somewhat more in Social Security taxes on average than they get back in benefits. They do get more back from Medicare than what they pay in taxes, but this is primarily because the United States pays so much more for health care than other wealthy countries. If the United States paid the same amount per person for its health care as other wealthy countries then Medicare taxes would roughly cover the cost of Medicare benefits. So this isn’t a story of the government being too generous to seniors, it’s a story of the government being too generous to doctors, drug companies, medical supply companies and others in the health care industry.

Samuelson is also badly confused when he tells readers:

“If lobbyists aim to empower the rich, they’re doing a lousy job. Democracy responds more to the mass of voters and to political crusades than to the wealthy or business interests. In the recent government shutdown, corporate America discovered that its influence on congressional Republicans was modest or nonexistent. It’s not that big companies and wealthy individuals are powerless, but their power is vastly exaggerated.

“The idea that government is routinely bought and sold by the rich is a source of widespread — but misleading — cynicism.”

Samuelson’s assertion is based on the fact that the rich don’t get many direct handouts from the government. But this is not what their lobbyists are trying to get. Instead they work to rig markets so that income will flow to their clients. This is easy to show in a large number of industries.

For example, the lobbyists have gotten drug companies patent monopolies that allow them to charge around $270 billion a year (@ 1.7 percent of GDP or 7.8 percent of the federal budget) more for their drugs than the free market price. They are currently drafting a trade deal, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, that will extend these monopolies in our trading partners thereby allowing the drug companies to charge higher prices overseas.

The financial industry has been able to arrange for too big to fail insurance that is equivalent to an annual subsidy of $80 billion a year (@ 0.5 percent of GDP or 2.0 percent of the federal budget). They are also likely to get a system under which Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac will be replaced by private banks issuing mortgages with a government guarantee. This is likely to mean tens of billions of dollars in fees each year for the banks involved.

There are many other ways in which lobbyists use their power to get the government to structure markets so that the rich get richer. Samuelson is right that this is mostly not done through direct government payouts, but that is ignoring what the lobbyists are doing. (For more information read the good book on the topic.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Kevin Drum poses a reasonable question about the existence of a retirement crisis in a recent blog post. He notes that retirement income projections from the Social Security Administration’s MINT model show income for older households rising from 1971 to the present, while incomes for those in the age 35 to 44 were nearly stagnant. The model also shows income for older households continuing to rise over the next three decades. Kevin’s conclusion is that we are wrong to spend a lot of time worrying about retirees, and would be wrong to consider increasing Social Security taxes on the working population to maintain scheduled benefits for Social Security recipients.

While the story of rising income for retirees is correct, there are several points to keep in mind. First, the main reason that income for the over 65 group has risen is that the real value of Social Security benefits has risen. Social Security benefits are tied to average wages, not median wages. This is important. Most of the upward redistribution of the last three decades has been to higher end wage earners like doctors, Wall Street types, and CEOs, not to profits. Since the average wage includes these high end earners, benefits will rise through time, pushing up retiree incomes. For the median household over age 65, Social Security benefits are more than 70 percent of their income, so the story of rising income is largely a story of rising Social Security benefits.

However, even with this increase in Social Security benefits, replacement rates at age 67 are projected to fall relative to lifetime wages (on a wage-adjusted basis) from 98 percent for the World War II babies to 89 percent for early baby boomers, 86 percent for later baby boomers and 84 percent for GenXers. There are several reasons for this drop. The most important is the rise in the normal retirement age from 65 for people who turned 62 before 2002 to 67 for people who turn 62 after 2022. This amounts to roughly a 12 percent cut in scheduled benefits. The other reason for the drop is the decline in non-Social Security income. This is primarily due to the fact that defined benefit pensions are rapidly disappearing and defined contribution pensions are not coming close to filling the gap.

It is also important that the over 65 population on average has a considerably longer life expectancy today and in the future than was the case in 1971. In 1971 someone turning age 65 could expect to live roughly 16 more years; today their life expectancy would be over 20 more years. This is a good thing of course, but it means that when we use the same age cutoff today as we did 40 plus years ago we are looking at a population that is much healthier, and therefore also more likely to be working, and further from death. If we adjusted our view to focus on the population that was within 16 years of hitting the end of their life expectancy, the story would not be as positive.

The data from the MINT model may also be somewhat misleading because it includes owner equivalent rent (OER) as income. While not having to pay rent is clearly an important savings to an older couple or individual that has paid off their mortgage, it can give an inaccurate picture of their income. There are many older couples or single individuals that live in large houses in which they raised their families. The imputed rent on such a house can be quite large relative to their income as retirees. (Imputed rent is almost one quarter of total consumer expenditures even though only two-thirds of families are homeowners.) There are undoubtedly many retirees who live in homes that would rent for an amount that is larger than their cash income, which will be primarily their Social Security check.

In principle it might be desirable for such people to move to smaller less expensive homes or apartments, but this is often not easy to do. Government policy that hugely subsidizes homeownership and denigrates renting is also not helpful in this respect.

The other part of the income picture overlooked is that almost all middle income retirees will be paying for Medicare Part B, the premium for which is taking up a large and growing share of their cash income. That premium has risen from roughly $250 a year (in 2013 dollars) to more than $1,200 a year at present. This difference would be equal to almost 5 percent of the income (excluding OER) of the typical senior. That means that if we took a measure of income that subtracted Medicare premiums (not co-pays and deductibles) it would show a considerably smaller increase than the MINT data. The higher costs faced by seniors for health care and other expenditures is the reason that the Census Bureau’s supplemental poverty measures shows a much higher poverty rate than the official measure.

Finally, there is the need to focus on the question of how well seniors are doing. Seniors income has been rising relative to the income of the typical working household because the typical working household is seeing their income redistributed to the Wall Street crew, CEOs, doctors and other members of the one percent. However, even with the relative gains for seniors, their income is still well below that of the working age population. The median person income for people over age 65 was $20,380 in 2012 compared to a median person income of $36,800 for someone between the ages of 35 to 44. Now we can point to the fact that incomes have been rising considerably faster for the over 65 group, but this would be like saying that we should be annoyed because women’s wages have been rising more rapidly than men’s wages. Women still earn much less for their work and seniors still get by on much less money than the working age population.

The bottom line is that it takes some pretty strange glasses to see the senior population as doing well either now or in the near future based on current economic conditions. We can argue about whether young people or old people have a tougher time, but it’s clear that the division between winners and losers is not aged based, but rather class based.

Kevin Drum poses a reasonable question about the existence of a retirement crisis in a recent blog post. He notes that retirement income projections from the Social Security Administration’s MINT model show income for older households rising from 1971 to the present, while incomes for those in the age 35 to 44 were nearly stagnant. The model also shows income for older households continuing to rise over the next three decades. Kevin’s conclusion is that we are wrong to spend a lot of time worrying about retirees, and would be wrong to consider increasing Social Security taxes on the working population to maintain scheduled benefits for Social Security recipients.

While the story of rising income for retirees is correct, there are several points to keep in mind. First, the main reason that income for the over 65 group has risen is that the real value of Social Security benefits has risen. Social Security benefits are tied to average wages, not median wages. This is important. Most of the upward redistribution of the last three decades has been to higher end wage earners like doctors, Wall Street types, and CEOs, not to profits. Since the average wage includes these high end earners, benefits will rise through time, pushing up retiree incomes. For the median household over age 65, Social Security benefits are more than 70 percent of their income, so the story of rising income is largely a story of rising Social Security benefits.

However, even with this increase in Social Security benefits, replacement rates at age 67 are projected to fall relative to lifetime wages (on a wage-adjusted basis) from 98 percent for the World War II babies to 89 percent for early baby boomers, 86 percent for later baby boomers and 84 percent for GenXers. There are several reasons for this drop. The most important is the rise in the normal retirement age from 65 for people who turned 62 before 2002 to 67 for people who turn 62 after 2022. This amounts to roughly a 12 percent cut in scheduled benefits. The other reason for the drop is the decline in non-Social Security income. This is primarily due to the fact that defined benefit pensions are rapidly disappearing and defined contribution pensions are not coming close to filling the gap.

It is also important that the over 65 population on average has a considerably longer life expectancy today and in the future than was the case in 1971. In 1971 someone turning age 65 could expect to live roughly 16 more years; today their life expectancy would be over 20 more years. This is a good thing of course, but it means that when we use the same age cutoff today as we did 40 plus years ago we are looking at a population that is much healthier, and therefore also more likely to be working, and further from death. If we adjusted our view to focus on the population that was within 16 years of hitting the end of their life expectancy, the story would not be as positive.

The data from the MINT model may also be somewhat misleading because it includes owner equivalent rent (OER) as income. While not having to pay rent is clearly an important savings to an older couple or individual that has paid off their mortgage, it can give an inaccurate picture of their income. There are many older couples or single individuals that live in large houses in which they raised their families. The imputed rent on such a house can be quite large relative to their income as retirees. (Imputed rent is almost one quarter of total consumer expenditures even though only two-thirds of families are homeowners.) There are undoubtedly many retirees who live in homes that would rent for an amount that is larger than their cash income, which will be primarily their Social Security check.

In principle it might be desirable for such people to move to smaller less expensive homes or apartments, but this is often not easy to do. Government policy that hugely subsidizes homeownership and denigrates renting is also not helpful in this respect.

The other part of the income picture overlooked is that almost all middle income retirees will be paying for Medicare Part B, the premium for which is taking up a large and growing share of their cash income. That premium has risen from roughly $250 a year (in 2013 dollars) to more than $1,200 a year at present. This difference would be equal to almost 5 percent of the income (excluding OER) of the typical senior. That means that if we took a measure of income that subtracted Medicare premiums (not co-pays and deductibles) it would show a considerably smaller increase than the MINT data. The higher costs faced by seniors for health care and other expenditures is the reason that the Census Bureau’s supplemental poverty measures shows a much higher poverty rate than the official measure.

Finally, there is the need to focus on the question of how well seniors are doing. Seniors income has been rising relative to the income of the typical working household because the typical working household is seeing their income redistributed to the Wall Street crew, CEOs, doctors and other members of the one percent. However, even with the relative gains for seniors, their income is still well below that of the working age population. The median person income for people over age 65 was $20,380 in 2012 compared to a median person income of $36,800 for someone between the ages of 35 to 44. Now we can point to the fact that incomes have been rising considerably faster for the over 65 group, but this would be like saying that we should be annoyed because women’s wages have been rising more rapidly than men’s wages. Women still earn much less for their work and seniors still get by on much less money than the working age population.

The bottom line is that it takes some pretty strange glasses to see the senior population as doing well either now or in the near future based on current economic conditions. We can argue about whether young people or old people have a tougher time, but it’s clear that the division between winners and losers is not aged based, but rather class based.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what millions are asking after reading a NYT piece on the need for additional spending to maintain and improve Germany’s infrastructure. The piece referred to a report from a government commission that put the additional spending needed at 7.2 billion euros a year, or $9.7 billion.

Since most readers probably do not have a very good idea of the size of Germany’s economy, they may not have a sense of how big a burden this poses. In 2014 Germany’s economy is projected to be a bit larger than 2.5 trillion euros. This means that this spending would be a bit less than 0.3 percent of GDP. It would roughly equivalent to spending $45 billion a year in the United States or less than 9 percent of the defense budget.

That’s what millions are asking after reading a NYT piece on the need for additional spending to maintain and improve Germany’s infrastructure. The piece referred to a report from a government commission that put the additional spending needed at 7.2 billion euros a year, or $9.7 billion.

Since most readers probably do not have a very good idea of the size of Germany’s economy, they may not have a sense of how big a burden this poses. In 2014 Germany’s economy is projected to be a bit larger than 2.5 trillion euros. This means that this spending would be a bit less than 0.3 percent of GDP. It would roughly equivalent to spending $45 billion a year in the United States or less than 9 percent of the defense budget.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The United States pays roughly twice as much for its doctors as people in other wealthy countries. The reason is that physicians in the United States use their political power to limit the supply of doctors both by restricted med school enrollments and excluding foreign trained physicians. (Yes, 25 percent of U.S. physicians are foreign-trained. Without protectionist measures that number could be more than 50 percent — just like with farm workers.) As a result of this protectionism almost one-third of doctors are in the richest one percent of the income distribution and the overwhelming majority are in the top 3 percent.

The profession is so powerful that papers like the Washington Post never even point out the obvious role of protectionism in an article that discusses limited access to physicians, like this one. It would be great if the media were allowed to talk about free trade even when it hurts the interests of the rich and powerful.

The United States pays roughly twice as much for its doctors as people in other wealthy countries. The reason is that physicians in the United States use their political power to limit the supply of doctors both by restricted med school enrollments and excluding foreign trained physicians. (Yes, 25 percent of U.S. physicians are foreign-trained. Without protectionist measures that number could be more than 50 percent — just like with farm workers.) As a result of this protectionism almost one-third of doctors are in the richest one percent of the income distribution and the overwhelming majority are in the top 3 percent.

The profession is so powerful that papers like the Washington Post never even point out the obvious role of protectionism in an article that discusses limited access to physicians, like this one. It would be great if the media were allowed to talk about free trade even when it hurts the interests of the rich and powerful.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Jeff Bezos is apparently having a hard time getting good help. Yesterday his paper mistook Paul Ryan, the Chair of the House Budget Committee, for a political philosopher. It ran a lengthy article telling readers about Ryan’s philosophy on taxes and poverty.

Of course the Post has no clue about Ryan’s philosophy, it knows what the politician says and what people close to him say. It may be news to the Post, although probably not Post readers, that politicians often don’t say what they really think. The piece tells us in the headline that Ryan “sets his sights on fighting poverty.” In fact, all we know is that Ryan wants to be perceived as setting his sights on fighting poverty.

The article itself gave no clue as to anything Ryan is considering that would qualify as a poverty fighting agenda. It talks about self-help and religious groups. These have existed forever with considerable government support. Their impact on poverty is very limited. The article gives no hint as to why anyone might think they would have a greater impact in the future, especially in a context where Ryan’s proposed cuts to a wide range of government programs would likely increase poverty.

The one substantive idea mentioned in the piece is school vouchers. This is hardly a new idea and one that has not been especially successful in practice.

The piece is also somewhat misleading when it tells readers:

“Unlike Romney, Ryan is no child of privilege. His dad died when he was 16, and he paid for college with a mix of Social Security survivors checks and maxed-out student loans, according to his brother, Tobin Ryan.”

Actually Ryan was from a relatively comfortable upper middle class family which owned a small business. While his family certainly was not as wealthy as Romney’s, it is misleading to describe Ryan as facing financial hardship in his upbringing.

Jeff Bezos is apparently having a hard time getting good help. Yesterday his paper mistook Paul Ryan, the Chair of the House Budget Committee, for a political philosopher. It ran a lengthy article telling readers about Ryan’s philosophy on taxes and poverty.

Of course the Post has no clue about Ryan’s philosophy, it knows what the politician says and what people close to him say. It may be news to the Post, although probably not Post readers, that politicians often don’t say what they really think. The piece tells us in the headline that Ryan “sets his sights on fighting poverty.” In fact, all we know is that Ryan wants to be perceived as setting his sights on fighting poverty.

The article itself gave no clue as to anything Ryan is considering that would qualify as a poverty fighting agenda. It talks about self-help and religious groups. These have existed forever with considerable government support. Their impact on poverty is very limited. The article gives no hint as to why anyone might think they would have a greater impact in the future, especially in a context where Ryan’s proposed cuts to a wide range of government programs would likely increase poverty.

The one substantive idea mentioned in the piece is school vouchers. This is hardly a new idea and one that has not been especially successful in practice.

The piece is also somewhat misleading when it tells readers:

“Unlike Romney, Ryan is no child of privilege. His dad died when he was 16, and he paid for college with a mix of Social Security survivors checks and maxed-out student loans, according to his brother, Tobin Ryan.”

Actually Ryan was from a relatively comfortable upper middle class family which owned a small business. While his family certainly was not as wealthy as Romney’s, it is misleading to describe Ryan as facing financial hardship in his upbringing.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

If the goal is to increase the inflation rate, then printing more money might seem like a reasonable way to go. But not in Germany. A Reuters piece on the NYT quotes German central bank head Jens Weidmann saying:

“There are no easy and quick ways out of this crisis. The money printer is definitely not the way to solve it.”

This appears in the context of a suggestion that the European Central Bank adopt quantitative easing to raise the inflation rate. So there you have it.

If the goal is to increase the inflation rate, then printing more money might seem like a reasonable way to go. But not in Germany. A Reuters piece on the NYT quotes German central bank head Jens Weidmann saying:

“There are no easy and quick ways out of this crisis. The money printer is definitely not the way to solve it.”

This appears in the context of a suggestion that the European Central Bank adopt quantitative easing to raise the inflation rate. So there you have it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT article on the growth of the car industry in Mexico told readers:

“Around 40 percent of all auto-industry jobs in North America are in Mexico, up from 27 percent in 2000 (the Midwest has about 30 percent), and experts say the growth is accelerating, especially in Guanajuato, where state officials have been increasing incentives.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2000 the United States had roughly 1,310,000 jobs in the auto industry. Currently employment in the sector is around 800,000, implying a drop of 38.9 percent. If employment in Canada followed the same pattern, then Mexico’s share of total industry employment in North America would have risen to more than 55 percent if it had stayed constant since 2000. Since Mexico’s share of total employment is now just 40 percent, it implies that it has gained share by seeing a less rapid decline, not by adding jobs. This doesn’t fit well with the main thesis of the article which is that a middle class is rising in Mexico.

A NYT article on the growth of the car industry in Mexico told readers:

“Around 40 percent of all auto-industry jobs in North America are in Mexico, up from 27 percent in 2000 (the Midwest has about 30 percent), and experts say the growth is accelerating, especially in Guanajuato, where state officials have been increasing incentives.”

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2000 the United States had roughly 1,310,000 jobs in the auto industry. Currently employment in the sector is around 800,000, implying a drop of 38.9 percent. If employment in Canada followed the same pattern, then Mexico’s share of total industry employment in North America would have risen to more than 55 percent if it had stayed constant since 2000. Since Mexico’s share of total employment is now just 40 percent, it implies that it has gained share by seeing a less rapid decline, not by adding jobs. This doesn’t fit well with the main thesis of the article which is that a middle class is rising in Mexico.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Andrew Ross Sorkin is angry that people are upset by seeing former Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner cash in on his public service by taking a job at the private equity company Warburg Pincus. In his column he complained:

“Within 24 hours of Timothy F. Geithner’s announcement on Saturday that he would join Warburg Pincus, the private equity firm, a parade of naysayers emerged, almost like clockwork, to criticize the former Treasury secretary’s move as a prime example of the evil of the government’s revolving door.”

As a Geithner defender, Sorkin apparently had hoped that critics would refrain from commenting until Geithner’s new job was no longer news.

Sorkin seems to miss the issue here. There is little reason to believe that Geithner’s experience in government would give him the sort of expertise that would be expected from a top executive at a private equity company. His record also does not demonstrate an especially astute understanding of the economy, since he consistently underestimated the duration and severity of the downturn, after completely missing the original collapse. The latter could be seen as pretty big gaffe, since he was pretty much sitting at ground zero at the time as president of the New York Fed.

While Geithner may not have expertise in investment or economics to sell, he does have political connections. This is presumably the reason that a private equity company would be willing to pay him a 7-figure salary and give him a top position. Sorkin is also being either naive or disingenuous when he comments on Geithner’s past opposition to the carried interest tax subsidy that benefits private equity firms like Warburg Pincus:

“If he changes course now that he is in industry, he deserves a drubbing.”

If Geithner changes courses now, he will probably not send a note to Sorkin notifying him of his new views on the issue. This change will likely be exhibited in close door meetings with Geithner’s former associates.

Perhaps some of the comment on Geithner’s new job was motivated by this line from a New York Magazine article:

“Geithner says it’s ‘extremely unlikely’ he will take a job in the world of finance, but the idea that he is somehow, secretly, working hand in hand with that community persists, and every once in a while someone pulls out records of his phone calls and meetings with CEOs as evidence.”

Presumably Geithner was reflecting some of the same sentiments as the critics derided by Sorkin when he indicated that he would probably not seek a job in finance.

Sorkin actually provides a valuable service with this piece since it displays the contempt with which elites view the rest of the country. At one point he favorably notes a comment from Ben White at Politico:

“Ben White of Politico on Monday joked sarcastically in his email newsletter about the criticism of Mr. Geithner’s new role: ‘Maybe he should have joined the priesthood.'”

Among the other positions open to Geithner were the presidency of his alma mater, Dartmouth, or possibly the head of a major charity (Sorkin suggests Red Cross). These are jobs that would pay high 6-figure or low 7-figure salaries. Such pay would put Geithner at the edge of the top 0.1 percent of the workforce and give him annual earnings 30 or more times as much as the typical worker. However for elite types, this would be the same as taking a vow of poverty and joining the priesthood.

Andrew Ross Sorkin is angry that people are upset by seeing former Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner cash in on his public service by taking a job at the private equity company Warburg Pincus. In his column he complained:

“Within 24 hours of Timothy F. Geithner’s announcement on Saturday that he would join Warburg Pincus, the private equity firm, a parade of naysayers emerged, almost like clockwork, to criticize the former Treasury secretary’s move as a prime example of the evil of the government’s revolving door.”

As a Geithner defender, Sorkin apparently had hoped that critics would refrain from commenting until Geithner’s new job was no longer news.

Sorkin seems to miss the issue here. There is little reason to believe that Geithner’s experience in government would give him the sort of expertise that would be expected from a top executive at a private equity company. His record also does not demonstrate an especially astute understanding of the economy, since he consistently underestimated the duration and severity of the downturn, after completely missing the original collapse. The latter could be seen as pretty big gaffe, since he was pretty much sitting at ground zero at the time as president of the New York Fed.

While Geithner may not have expertise in investment or economics to sell, he does have political connections. This is presumably the reason that a private equity company would be willing to pay him a 7-figure salary and give him a top position. Sorkin is also being either naive or disingenuous when he comments on Geithner’s past opposition to the carried interest tax subsidy that benefits private equity firms like Warburg Pincus:

“If he changes course now that he is in industry, he deserves a drubbing.”

If Geithner changes courses now, he will probably not send a note to Sorkin notifying him of his new views on the issue. This change will likely be exhibited in close door meetings with Geithner’s former associates.

Perhaps some of the comment on Geithner’s new job was motivated by this line from a New York Magazine article:

“Geithner says it’s ‘extremely unlikely’ he will take a job in the world of finance, but the idea that he is somehow, secretly, working hand in hand with that community persists, and every once in a while someone pulls out records of his phone calls and meetings with CEOs as evidence.”

Presumably Geithner was reflecting some of the same sentiments as the critics derided by Sorkin when he indicated that he would probably not seek a job in finance.

Sorkin actually provides a valuable service with this piece since it displays the contempt with which elites view the rest of the country. At one point he favorably notes a comment from Ben White at Politico:

“Ben White of Politico on Monday joked sarcastically in his email newsletter about the criticism of Mr. Geithner’s new role: ‘Maybe he should have joined the priesthood.'”

Among the other positions open to Geithner were the presidency of his alma mater, Dartmouth, or possibly the head of a major charity (Sorkin suggests Red Cross). These are jobs that would pay high 6-figure or low 7-figure salaries. Such pay would put Geithner at the edge of the top 0.1 percent of the workforce and give him annual earnings 30 or more times as much as the typical worker. However for elite types, this would be the same as taking a vow of poverty and joining the priesthood.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión