It’s hard to get news over at Fox on 15th Street, buried away in downtown Washington, five blocks from the White House. That presumably is why the Washington Post had a front page article discussing the extent to which young people are signing for the health care exchanges set up under Obamacare. The piece reports on the outreach effort to sign up:

“the healthy Americans in their 20s and 30s who are key to making the economics of the new health-care law work.”

In fact there is not a special need to sign up young healthy people as opposed to healthy people of all ages. Kaiser Family Foundation did an analysis last week showing that it would have relatively little impact on the cost of the program even if the number of young people enrolling fell far below their share of the population. While young people do have lower costs on average, they also pay lower premiums. While these are not completely offsetting the difference will have little impact on the costs of the program.

The conclusion of the Kaiser study is that the exchanges need healthy people of all ages. It doesn’t especially matter if they are young. (A healthy 55-year-old pays three times as much as a healthy 30-year-old.) The real concern is a skewing based on health status, not age.

It’s hard to get news over at Fox on 15th Street, buried away in downtown Washington, five blocks from the White House. That presumably is why the Washington Post had a front page article discussing the extent to which young people are signing for the health care exchanges set up under Obamacare. The piece reports on the outreach effort to sign up:

“the healthy Americans in their 20s and 30s who are key to making the economics of the new health-care law work.”

In fact there is not a special need to sign up young healthy people as opposed to healthy people of all ages. Kaiser Family Foundation did an analysis last week showing that it would have relatively little impact on the cost of the program even if the number of young people enrolling fell far below their share of the population. While young people do have lower costs on average, they also pay lower premiums. While these are not completely offsetting the difference will have little impact on the costs of the program.

The conclusion of the Kaiser study is that the exchanges need healthy people of all ages. It doesn’t especially matter if they are young. (A healthy 55-year-old pays three times as much as a healthy 30-year-old.) The real concern is a skewing based on health status, not age.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post just loves anything that is labeled as a free trade agreement. (I’m going to call my old car a “free trade agreement” and sell it to the Post for a fortune.) Today it ran a piece on the Trans-Pacific Partnership that had the sub-head:

“goal of talks with Pacific region is a freer flow of world commerce.”

While this is also asserted in the article itself, it is not true as the article makes clear. One of the main purposes of the deal is strengthening patent and copyright protection and other claims to intellectual property.

Note the word “protection.” This aspect of the deal is about obstructing the free flow of international commerce. These forms of protectionism will raise the price of many items by several thousand percent above their free market price. They will cause large amounts of resource to be wasted to legal suits, lobbying, marketing, and other forms of rent-seeking activity.

It is possible to argue for the merits of increased protection for intellectual property claims, but it is just flat wrong to describe this as creating a freer flow of international commerce. These forms of protection are 180 degrees at odds with free trade.

The Washington Post just loves anything that is labeled as a free trade agreement. (I’m going to call my old car a “free trade agreement” and sell it to the Post for a fortune.) Today it ran a piece on the Trans-Pacific Partnership that had the sub-head:

“goal of talks with Pacific region is a freer flow of world commerce.”

While this is also asserted in the article itself, it is not true as the article makes clear. One of the main purposes of the deal is strengthening patent and copyright protection and other claims to intellectual property.

Note the word “protection.” This aspect of the deal is about obstructing the free flow of international commerce. These forms of protectionism will raise the price of many items by several thousand percent above their free market price. They will cause large amounts of resource to be wasted to legal suits, lobbying, marketing, and other forms of rent-seeking activity.

It is possible to argue for the merits of increased protection for intellectual property claims, but it is just flat wrong to describe this as creating a freer flow of international commerce. These forms of protection are 180 degrees at odds with free trade.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Timothy Lee says that Paul Krugman got it wrong about the resources being wasted in the process of bitcoin mining. Krugman wrote a column based on a NYT piece about a massive bank of computers located in Iceland (low cost electricity) that is devoted to developing complex algorithms that allow the owners to get a large share of newly minted bitcoins.

Lee’s complaint against Krugman is that this mining is actually part of the Bitcoin transactions process. The correct answer to Lee is, so what?

Suppose that some of the people engaged in gold mining are actually armed guards who are there to protect any gold that is recovered. Would these mean that the labor of the armed guards is not being wasted in this totally unproductive exercise? The same applies to the banks of computers calculating algorithms. It doesn’t change anything if they are part of the processing network.

Of course when we have governments that are determined to waste resources by running budgets that leave tens of millions unemployed, even nonsense like Bitcoin mining can be a positive, as Keynes noted. But Krugman is 100 percent right, bitcoin mining is an incredible waste of potentially productive resources, and I said it first.

Timothy Lee says that Paul Krugman got it wrong about the resources being wasted in the process of bitcoin mining. Krugman wrote a column based on a NYT piece about a massive bank of computers located in Iceland (low cost electricity) that is devoted to developing complex algorithms that allow the owners to get a large share of newly minted bitcoins.

Lee’s complaint against Krugman is that this mining is actually part of the Bitcoin transactions process. The correct answer to Lee is, so what?

Suppose that some of the people engaged in gold mining are actually armed guards who are there to protect any gold that is recovered. Would these mean that the labor of the armed guards is not being wasted in this totally unproductive exercise? The same applies to the banks of computers calculating algorithms. It doesn’t change anything if they are part of the processing network.

Of course when we have governments that are determined to waste resources by running budgets that leave tens of millions unemployed, even nonsense like Bitcoin mining can be a positive, as Keynes noted. But Krugman is 100 percent right, bitcoin mining is an incredible waste of potentially productive resources, and I said it first.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Lydia DePillis warns us in the Post of 8 ways that robots will take our jobs. It is amazing how the media have managed to hype the fear of robots taking our jobs at the same time that they have built up fears over huge budget deficits bankrupting the country. You don’t see the connection? Maybe you should be an economics reporter for a leading national news outlet.

Okay, let’s get to basics. The robots taking our jobs story is a story of labor surplus, too many workers, too few jobs. Everything that needs to be done is being done by the robots. There is nothing for the rest of us to do but watch.

There can of course be issues of distribution. If the one percent are able to write laws that allow them to claim everything the robots produce then they can make most of us very poor. But this is still a story of society of plenty. We can have all the food, shelter, health care, clean energy, etc. that we need; the robots can do it for us.

Okay, now let’s flip over to the budget crisis that has the folks at the Washington Post losing sleep. This is a story of scarcity. We are spending so much money on our parents’ and grandparents’ Social Security and Medicare that there is no money left to educate our kids.

Some confused souls may say that the problem may not be an economic one, but rather a fiscal problem. The government can’t raise the tax revenue to pay for both the Social Security and Medicare for the elderly and the education of our kids. This is confused because if we are living in the world where the robots are doing all the work then the government really doesn’t need to raise tax revenue, it can just print the money it needs to back its payments.

Okay, now everyone is completely appalled. The government is just going to print trillions of dollars? That will send inflation through the roof, right? Not in the world where robots are doing all the work it won’t. If we print money it will create more demands for goods and services, which the robots will be happy to supply. As every intro econ graduate knows, inflation is a story of too much money chasing too few goods and services. But in the robots do everything story, the goods and services are quickly generated to meet the demand. Where’s the inflation, robots demanding higher wages?

In short, you can craft a story where we have huge advances in robot technology so that the need for human labor is drastically reduced. You can also craft a story where an aging population leads to too few workers being left to support too many retirees. However, you can’t believe both at the same time unless you write on economic issues for the Washington Post.

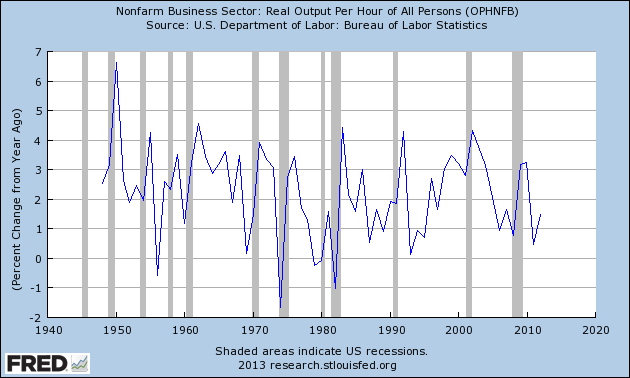

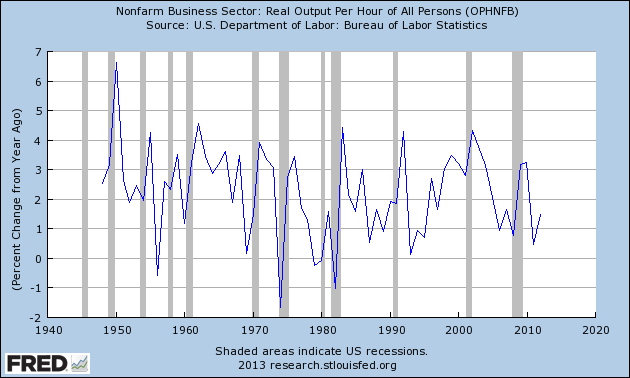

Just in case anyone cares about what the data says on these issues, the robots don’t seem to be winning out too quickly. Productivity growth has slowed sharply over the last three years and it is well below the pace of 1947-73 golden age. (Robots are just another form of good old-fashioned productivity growth.)

On the other hand, the scarcity mongers don’t have much of a case either. Even if productivity growth stays at just a 1.5 percent annual rate its impact on raising wages and living standards will swamp any conceivable tax increases associated with caring for a larger population of retirees.

Lydia DePillis warns us in the Post of 8 ways that robots will take our jobs. It is amazing how the media have managed to hype the fear of robots taking our jobs at the same time that they have built up fears over huge budget deficits bankrupting the country. You don’t see the connection? Maybe you should be an economics reporter for a leading national news outlet.

Okay, let’s get to basics. The robots taking our jobs story is a story of labor surplus, too many workers, too few jobs. Everything that needs to be done is being done by the robots. There is nothing for the rest of us to do but watch.

There can of course be issues of distribution. If the one percent are able to write laws that allow them to claim everything the robots produce then they can make most of us very poor. But this is still a story of society of plenty. We can have all the food, shelter, health care, clean energy, etc. that we need; the robots can do it for us.

Okay, now let’s flip over to the budget crisis that has the folks at the Washington Post losing sleep. This is a story of scarcity. We are spending so much money on our parents’ and grandparents’ Social Security and Medicare that there is no money left to educate our kids.

Some confused souls may say that the problem may not be an economic one, but rather a fiscal problem. The government can’t raise the tax revenue to pay for both the Social Security and Medicare for the elderly and the education of our kids. This is confused because if we are living in the world where the robots are doing all the work then the government really doesn’t need to raise tax revenue, it can just print the money it needs to back its payments.

Okay, now everyone is completely appalled. The government is just going to print trillions of dollars? That will send inflation through the roof, right? Not in the world where robots are doing all the work it won’t. If we print money it will create more demands for goods and services, which the robots will be happy to supply. As every intro econ graduate knows, inflation is a story of too much money chasing too few goods and services. But in the robots do everything story, the goods and services are quickly generated to meet the demand. Where’s the inflation, robots demanding higher wages?

In short, you can craft a story where we have huge advances in robot technology so that the need for human labor is drastically reduced. You can also craft a story where an aging population leads to too few workers being left to support too many retirees. However, you can’t believe both at the same time unless you write on economic issues for the Washington Post.

Just in case anyone cares about what the data says on these issues, the robots don’t seem to be winning out too quickly. Productivity growth has slowed sharply over the last three years and it is well below the pace of 1947-73 golden age. (Robots are just another form of good old-fashioned productivity growth.)

On the other hand, the scarcity mongers don’t have much of a case either. Even if productivity growth stays at just a 1.5 percent annual rate its impact on raising wages and living standards will swamp any conceivable tax increases associated with caring for a larger population of retirees.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

When people just start making things up it usually means that they don’t have much of an argument. That appears to be the case with the bashers of Obamacare over at the Wall Street Journal.

Robert Grady, a managing director of a private equity company and top adviser to New Jersey Governor Chris Christie told readers:

“For most of this year, the overwhelming majority of jobs added to the U.S. economy have been part-time, not full-time. Gallup’s payroll-to-population ratio, the proportion of the American population working full time, has dropped almost two full percentage points in the last year, to 43.8%.”

These are great numbers because they can be easily checked. If we go the Bureau of Labor Statistics website (Table A-8), we find that the number of people listed as part for economic reasons fell from 8,138,000 in November of last year to 7,719,000 in November of this year, a decline of 419,000.

The number of people opting to work part-time rose from 18,594,000 in November of last year to 18,876,000 in November of 2013, a gain of 282,000. If we add the drop in part-time for economic reasons to the gain in voluntary part-time, we get a drop in total part-time employment of 137,000.

By comparison, total employment (Table A-1) rose from 143,277,000 last November to 144,386,000, a gain of 1,109,000. Okay, so we have that part-time employment fell by 137,000 while total employment rose by 1.1 million, how do Grady and the WSJ get that part-time employment is exploding because of Obamacare?

Hey, night is day, black is white, up is down, meet the just make it up crew at the WSJ.

When people just start making things up it usually means that they don’t have much of an argument. That appears to be the case with the bashers of Obamacare over at the Wall Street Journal.

Robert Grady, a managing director of a private equity company and top adviser to New Jersey Governor Chris Christie told readers:

“For most of this year, the overwhelming majority of jobs added to the U.S. economy have been part-time, not full-time. Gallup’s payroll-to-population ratio, the proportion of the American population working full time, has dropped almost two full percentage points in the last year, to 43.8%.”

These are great numbers because they can be easily checked. If we go the Bureau of Labor Statistics website (Table A-8), we find that the number of people listed as part for economic reasons fell from 8,138,000 in November of last year to 7,719,000 in November of this year, a decline of 419,000.

The number of people opting to work part-time rose from 18,594,000 in November of last year to 18,876,000 in November of 2013, a gain of 282,000. If we add the drop in part-time for economic reasons to the gain in voluntary part-time, we get a drop in total part-time employment of 137,000.

By comparison, total employment (Table A-1) rose from 143,277,000 last November to 144,386,000, a gain of 1,109,000. Okay, so we have that part-time employment fell by 137,000 while total employment rose by 1.1 million, how do Grady and the WSJ get that part-time employment is exploding because of Obamacare?

Hey, night is day, black is white, up is down, meet the just make it up crew at the WSJ.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT gave readers an excellent example of how the financial sector can lead to an enormous waste of economic resources. It reported on a massive set of sophisticated computers in Iceland that is devoted to the sole purpose of “mining” bitcoins. The point is that these computers are used to carry through complex algorithms more quickly than competitors in order to lay claim to new bitcoins as they become available on the markets.

While this can be quite profitable to an individual or firm that successfully claims a substantial portion of the newly created bit coins, it provides nothing of value to the economy as a whole. It is a case of pure rent-seeking, where large amount of resources are devoted to pulling away wealth that is created in other sectors. This is the story of much of the activity in the financial sector, such as high-frequency trading or the tax gaming that is the specialty of the private equity industry, but in few cases is the rent-seeking so clear and unambiguous. The NYT did a valuable service by presenting this example.

The NYT gave readers an excellent example of how the financial sector can lead to an enormous waste of economic resources. It reported on a massive set of sophisticated computers in Iceland that is devoted to the sole purpose of “mining” bitcoins. The point is that these computers are used to carry through complex algorithms more quickly than competitors in order to lay claim to new bitcoins as they become available on the markets.

While this can be quite profitable to an individual or firm that successfully claims a substantial portion of the newly created bit coins, it provides nothing of value to the economy as a whole. It is a case of pure rent-seeking, where large amount of resources are devoted to pulling away wealth that is created in other sectors. This is the story of much of the activity in the financial sector, such as high-frequency trading or the tax gaming that is the specialty of the private equity industry, but in few cases is the rent-seeking so clear and unambiguous. The NYT did a valuable service by presenting this example.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It sure seems that way as he implies that greater patent and copyright protection are the wave of the future. He tells readers:

“The growing commitment of the American political system to intellectual-property protection and enforcement, like that in trade treaties, also hasn’t gained much explicit notice. This shift of priorities is likely to become more important as economies move toward creative production and information technology.”

Already we lose close to $270 billion in patent rents on pharmaceuticals alone. This is roughly 1.6 percent of GDP or more than three times what the government spends on food stamps each year. This is money that is wasted paying more than free market price for drugs, which would almost invariably be cheap ($5-$10 per prescription) absent these government granted monopolies.

Even worse, patents monopolies give huge incentives to drug companies to lie to the public about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs. They routinely conceal or misrepresent information, just as economic theory predicts. There are more efficient ways to finance the development of drugs, but apparently Cowen thinks the drug industry will be sufficiently powerful from having them be considered in public policy debates. (Thus far he has been right.)

Government granted patent monopolies also likely slow innovation in other areas as well, most notably in the high tech sector where companies like Apple and Samsung compete at least as much in the courtroom over patent suits as in the marketplace.

It sure seems that way as he implies that greater patent and copyright protection are the wave of the future. He tells readers:

“The growing commitment of the American political system to intellectual-property protection and enforcement, like that in trade treaties, also hasn’t gained much explicit notice. This shift of priorities is likely to become more important as economies move toward creative production and information technology.”

Already we lose close to $270 billion in patent rents on pharmaceuticals alone. This is roughly 1.6 percent of GDP or more than three times what the government spends on food stamps each year. This is money that is wasted paying more than free market price for drugs, which would almost invariably be cheap ($5-$10 per prescription) absent these government granted monopolies.

Even worse, patents monopolies give huge incentives to drug companies to lie to the public about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs. They routinely conceal or misrepresent information, just as economic theory predicts. There are more efficient ways to finance the development of drugs, but apparently Cowen thinks the drug industry will be sufficiently powerful from having them be considered in public policy debates. (Thus far he has been right.)

Government granted patent monopolies also likely slow innovation in other areas as well, most notably in the high tech sector where companies like Apple and Samsung compete at least as much in the courtroom over patent suits as in the marketplace.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Sorry, for family reasons I am seeing the Sunday morning shows. It’s amazing these things exist. David Gregory is interviewing Yuval Levin about his book Tyranny of Reason, Imagining the Future, The Great Debate: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, and the Birth of Left and Right.

The book sounds like collection of painful cliches, the left likes activist government, the right believes in leaving civil society to work things out for itself. Really? So the patents and copyrights that shift far more money to the wealthy than food stamps and TANF shift to the poor are just civil society, not activist government. Trade policies that put downward pressure on the wages of most workers, while largely protecting doctors and other highly paid professionals are also just civil society, not activist government. Bank bailouts and no cost too big to fail insurance for the big banks are just civil society, not activist government.

There is a much longer list of such policies in my book The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive (free download available). There is zero evidence that either Levin or Gregory has ever heard of any of these arguments. They are determined to just repeat tired cliches that have nothing to do with actual politics.

The cliches of course do help to advance a right-wing agenda. It sounds much better to say that the rich got really rich by the natural workings of the market rather than by paying off the ref to write the rules to benefit themselves. The reality might be much closer to the latter, but Gregory and Levin apparently don’t even want anyone to think about such possibilities.

Sorry, for family reasons I am seeing the Sunday morning shows. It’s amazing these things exist. David Gregory is interviewing Yuval Levin about his book Tyranny of Reason, Imagining the Future, The Great Debate: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, and the Birth of Left and Right.

The book sounds like collection of painful cliches, the left likes activist government, the right believes in leaving civil society to work things out for itself. Really? So the patents and copyrights that shift far more money to the wealthy than food stamps and TANF shift to the poor are just civil society, not activist government. Trade policies that put downward pressure on the wages of most workers, while largely protecting doctors and other highly paid professionals are also just civil society, not activist government. Bank bailouts and no cost too big to fail insurance for the big banks are just civil society, not activist government.

There is a much longer list of such policies in my book The End of Loser Liberalism: Making Markets Progressive (free download available). There is zero evidence that either Levin or Gregory has ever heard of any of these arguments. They are determined to just repeat tired cliches that have nothing to do with actual politics.

The cliches of course do help to advance a right-wing agenda. It sounds much better to say that the rich got really rich by the natural workings of the market rather than by paying off the ref to write the rules to benefit themselves. The reality might be much closer to the latter, but Gregory and Levin apparently don’t even want anyone to think about such possibilities.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Commerce Department released its second revision to the third quarter GDP numbers on Friday. It showed the economy growing 4.1 percent, which was better than the earlier reports and more than most analysts had expected. However, the Post got more than a bit carried away on this one, telling readers in the second sentence of its article on the report:

“The Commerce Department reported that the nation’s gross domestic product grew at a 4.1 percent annual rate during the third quarter — the best showing since 1992.”

Really? How about the 4.9 percent growth rate in the fourth quarter of 2011, less than two years ago? Then we had a 4.9 percent growth rate in the first quarter of 2006 and a 4.5 percent growth rate in the first quarter of 2005. In total I find 17 quarters since 1992 with growth rates higher than 4.1 percent. So that one seems a bit off.

Furthermore, as the article notes in passing, most of the better than expected performance was due to inventory accumulations which added 1.7 percentage points to the growth reported for the quarter. The economy reportedly accumulated inventories at annual rate of $115.7 billion in the third quarter, an absolute pace exceeded only by the $116.2 billion rate in the third quarter of 2011. In the fourth quarter, if the economy adds inventories at the same rate as it did in the prior two years, and the rest of the economy grows at the same pace as it did in the third quarter, then the growth rate will be less than 1.0 percent.

The Commerce Department released its second revision to the third quarter GDP numbers on Friday. It showed the economy growing 4.1 percent, which was better than the earlier reports and more than most analysts had expected. However, the Post got more than a bit carried away on this one, telling readers in the second sentence of its article on the report:

“The Commerce Department reported that the nation’s gross domestic product grew at a 4.1 percent annual rate during the third quarter — the best showing since 1992.”

Really? How about the 4.9 percent growth rate in the fourth quarter of 2011, less than two years ago? Then we had a 4.9 percent growth rate in the first quarter of 2006 and a 4.5 percent growth rate in the first quarter of 2005. In total I find 17 quarters since 1992 with growth rates higher than 4.1 percent. So that one seems a bit off.

Furthermore, as the article notes in passing, most of the better than expected performance was due to inventory accumulations which added 1.7 percentage points to the growth reported for the quarter. The economy reportedly accumulated inventories at annual rate of $115.7 billion in the third quarter, an absolute pace exceeded only by the $116.2 billion rate in the third quarter of 2011. In the fourth quarter, if the economy adds inventories at the same rate as it did in the prior two years, and the rest of the economy grows at the same pace as it did in the third quarter, then the growth rate will be less than 1.0 percent.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión