Do you remember back when we were worried that robots will take all of the jobs? There will be no work for any of us because we will have all been replaced by robots.

It turns out that we have even more to worry about. AP says that because of declining birth rates and increasing life expectancies, we face a huge demographic crunch. We will have hordes of retirees and no one to to do the work. Now that sounds really scary, at the same time we have no jobs because the robots took them we must also struggle with the fact that we have no one to do the work because everyone is old and retired.

Yes, these are the complete opposite arguments. It is possible for one or the other to be true, but only in Washington can both be problems simultaneously. In this case, I happen to be a good moderate and say that neither is true. There is no plausible story in which robots are going to make us all unemployed any time in the foreseeable future. Nor is there a case that the demographic will impoverish us.

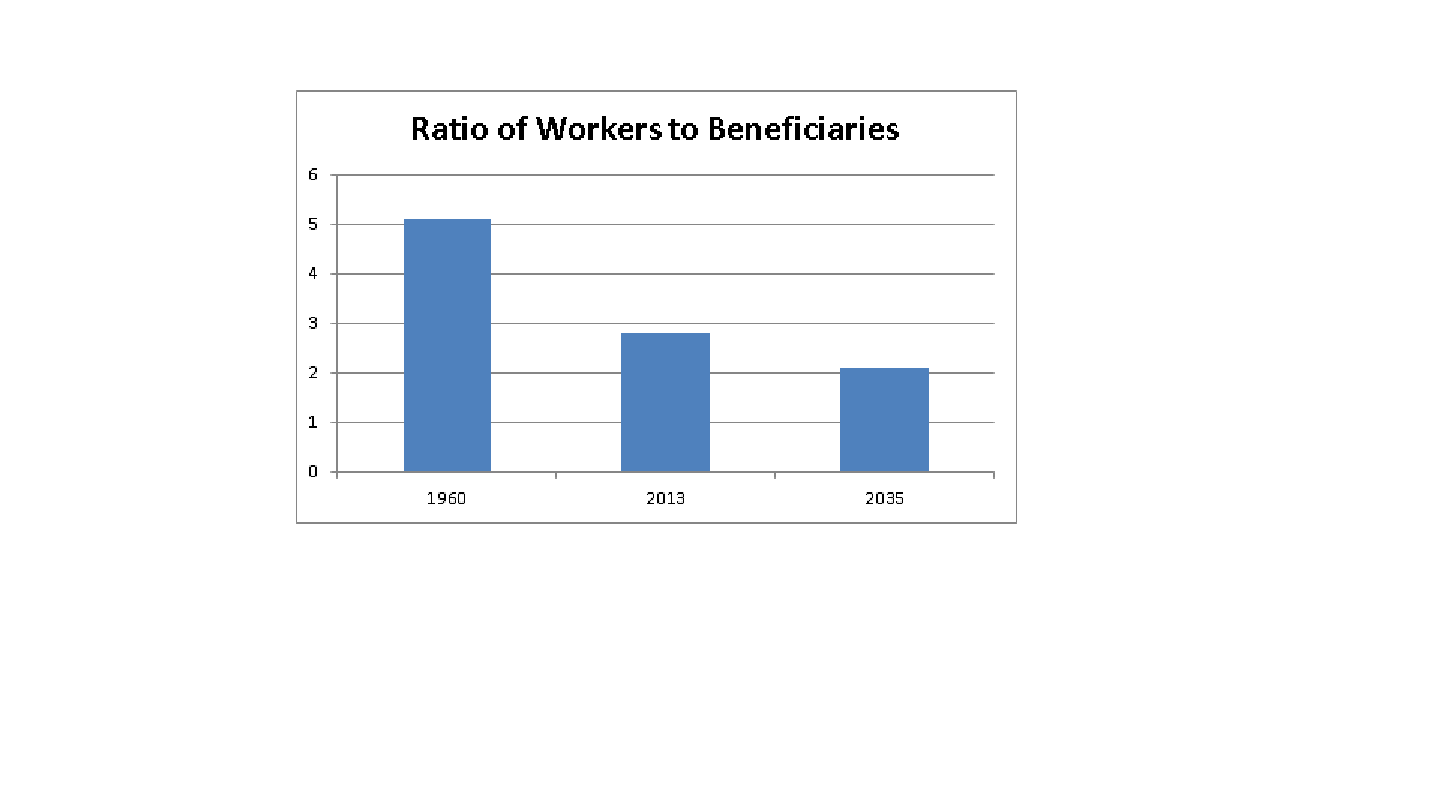

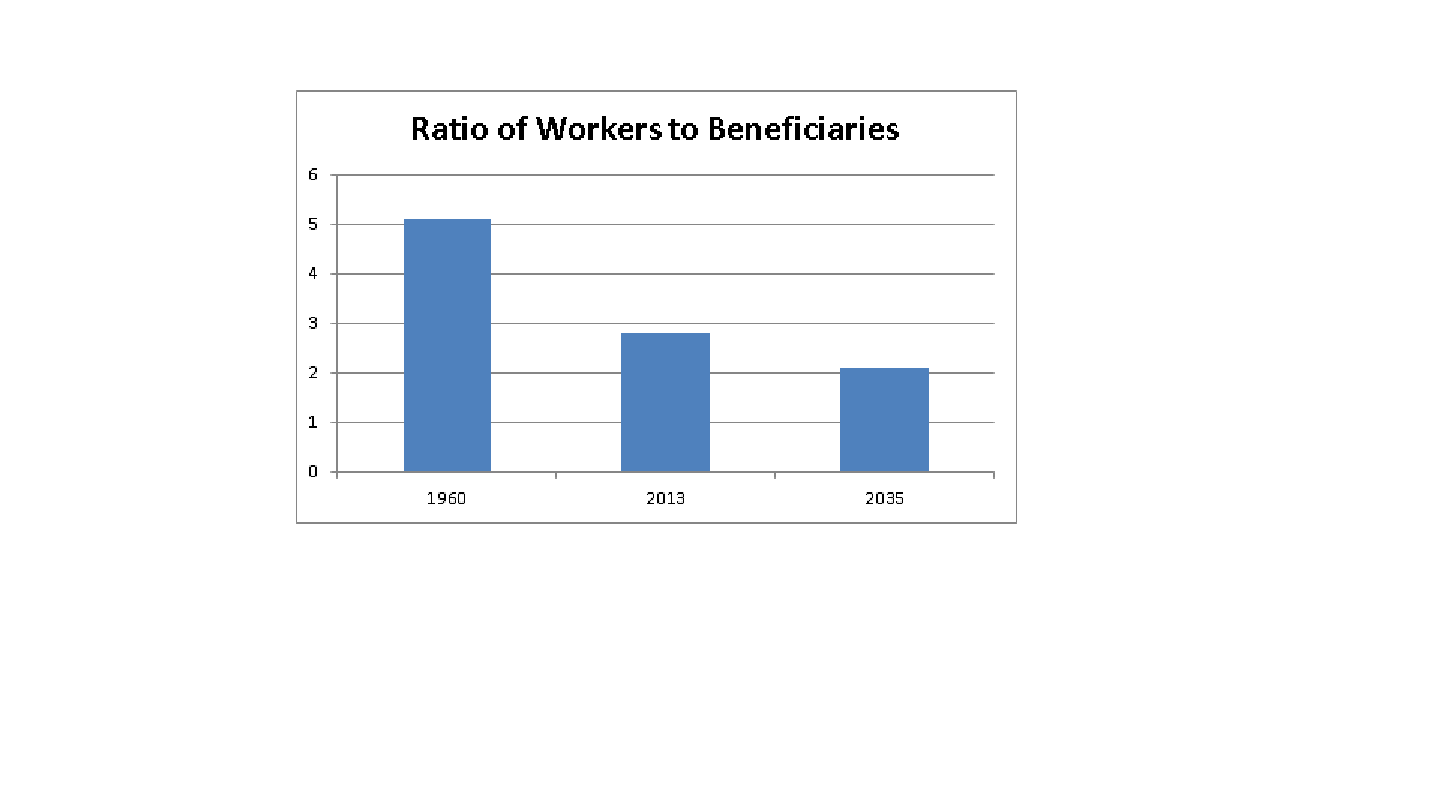

The basic story is that we have a rising ratio of retirees to workers, which should promote outraged cries of “so what?” Yes folks, we have had rising ratios of retirees to workers for a long time. In 1960 there was just one retiree for every five workers. Today there is one retiree for every 2.8 workers, and the Social Security trustees tell us that in 2035 there will be one retiree for every 2.1 workers.

Source: Social Security Trustees Report.

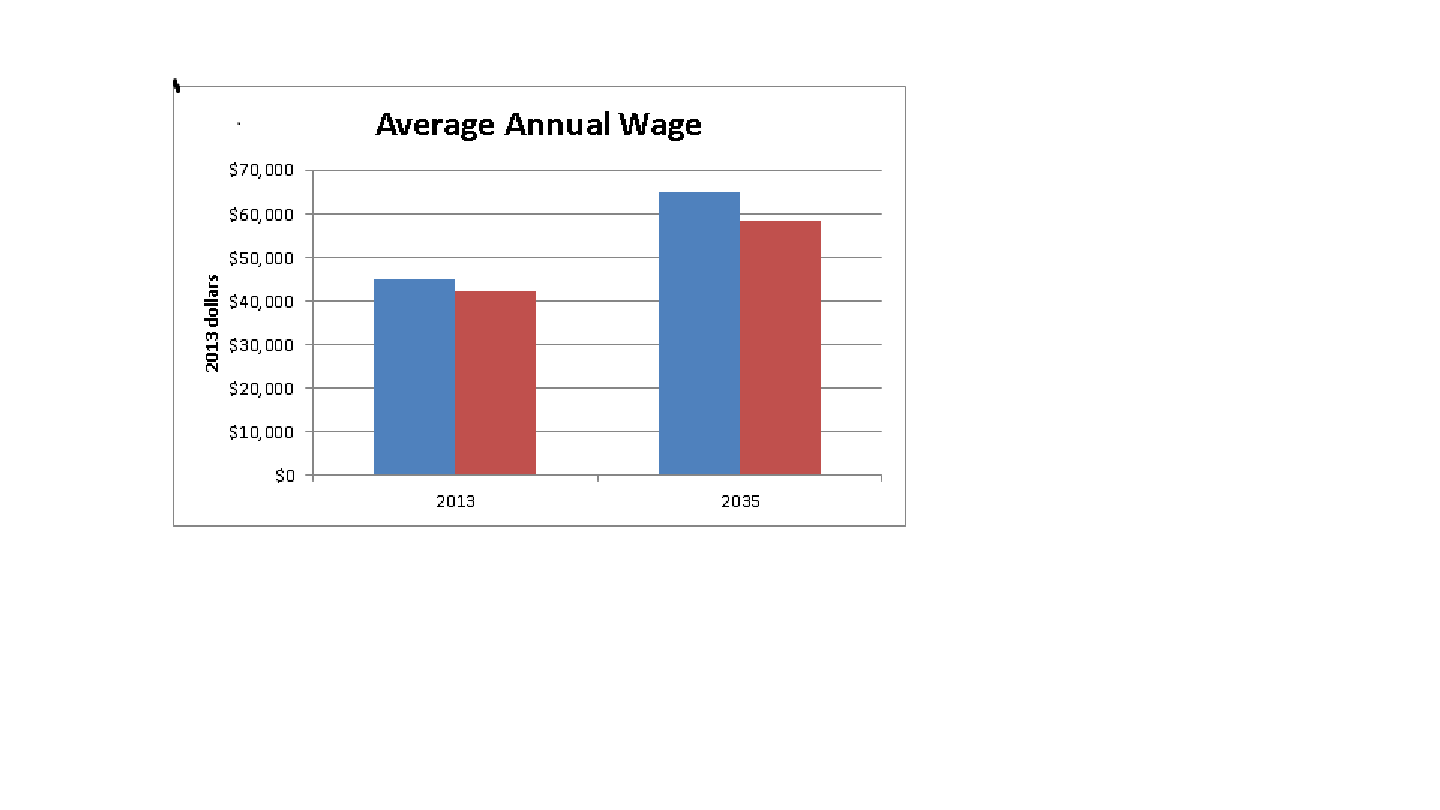

Just as the fall in the ratio of workers to retirees between 1960 and 2013 did not prevent both workers and retirees from enjoying substantially higher living standards, there is no reason to expect the further decline in the ratio to 2035 to lead to a fall in living standards.

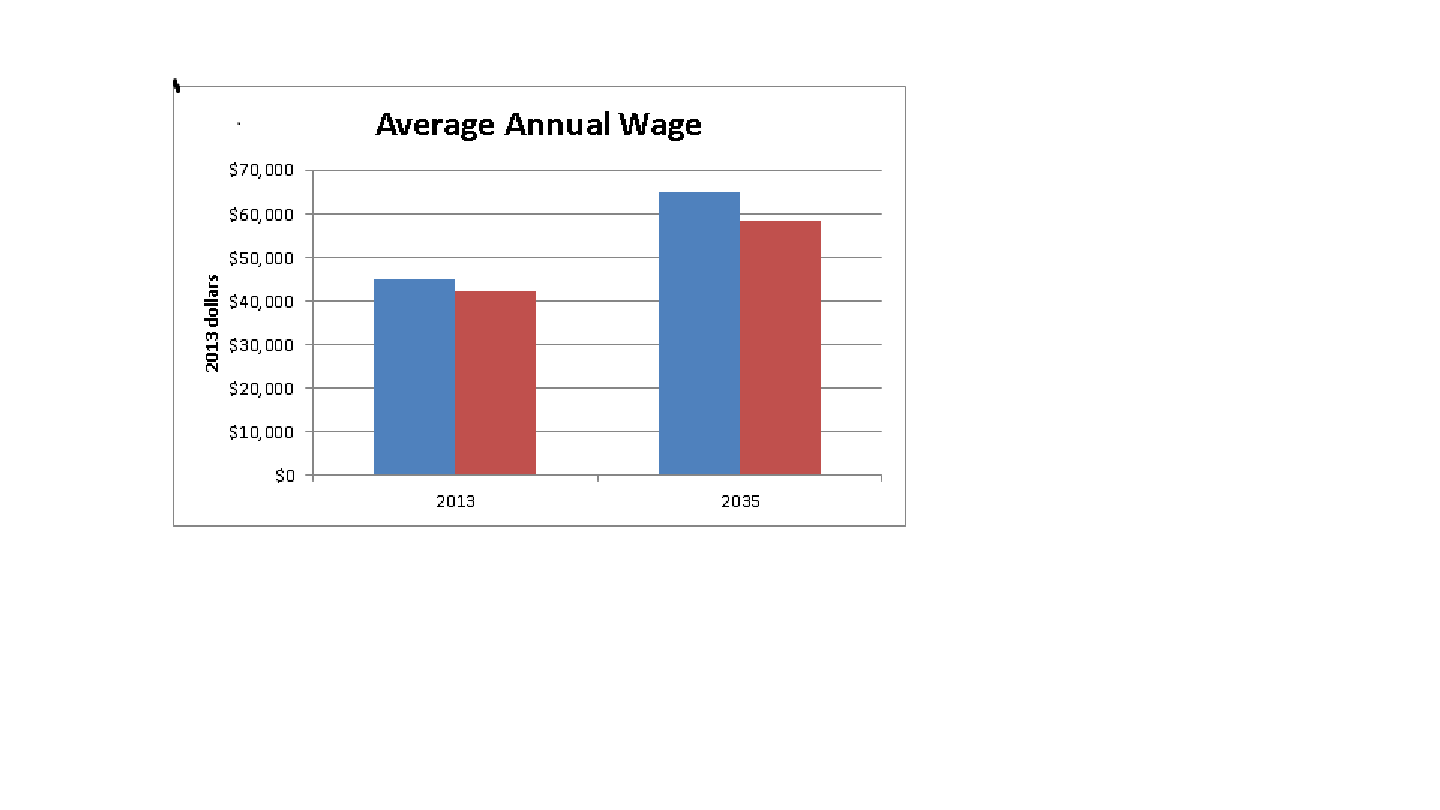

This point can be seen by comparing the average wage in 2013 with the average wage projected for 2035. The chart also includes the after-Social Security tax wage. The figure for 2035 assumes a 4.0 percentage point rise in the Social Security tax, an increase that is far larger than would be needed to keep the program fully funded under almost any conceivable circumstances. Even in this case, the average after tax wage would more than 38 percent higher than it is today.

Source: Social Security Trustees Report.

There is of course an issue of distribution. Most workers have not seen much benefit from the growth in average wages over the last three decades as most of the gains have gone to those at the top. But this points out yet again the urgency of addressing wage inequality. A continuing upward redistribution of income could make our children poor. Social Security and Medicare will not.

Finally, this AP article warns of the demographic nightmare facing China. Really?

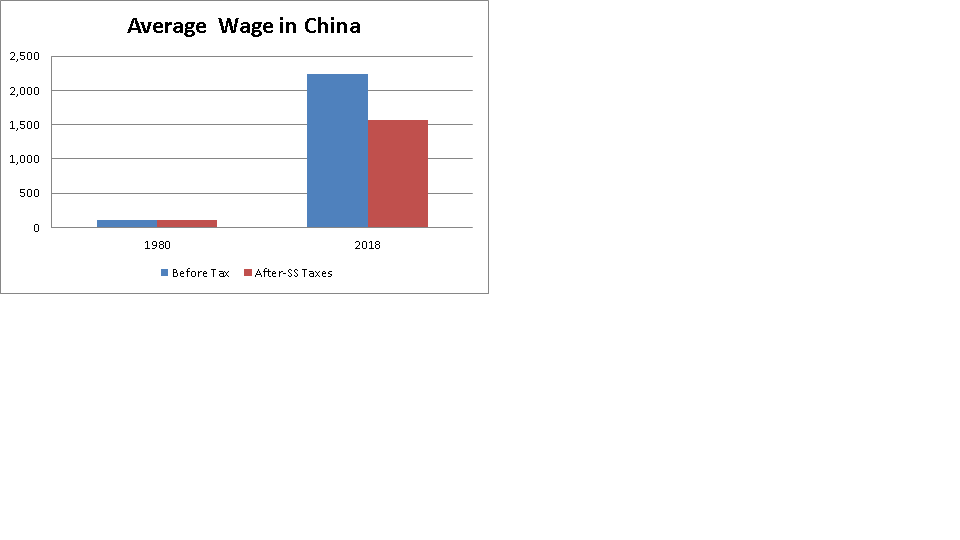

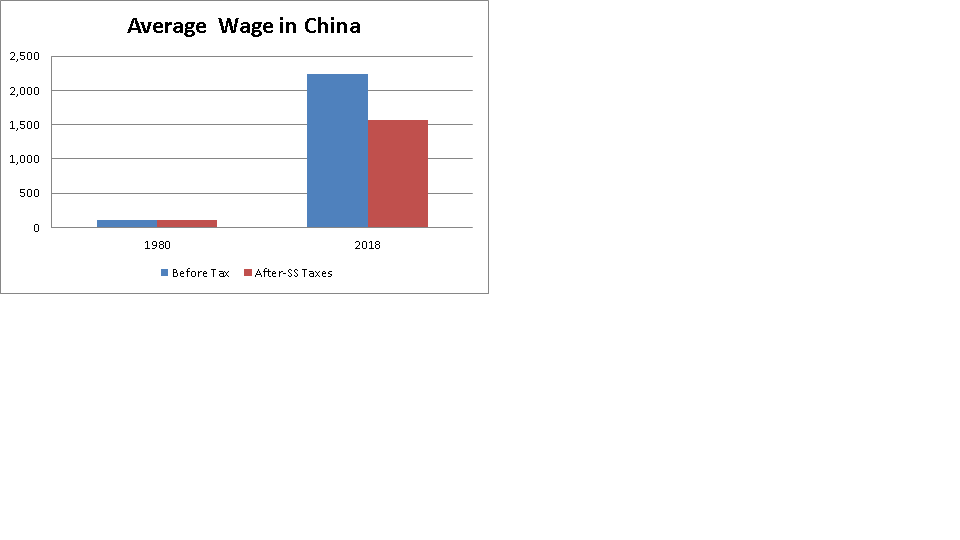

China has seen incredible economic growth over the last three decades. As a result it is hugely richer today than it was in 1980. The chart below shows the ratio of real per capita income projected by the IMF for China in 2018 compared to its 1980 level. The projection for 2018 is more than 22 times as high as the 1980 level. The chart shows average wages under the assumption that wages grew in step with per capita income and a hypothetical after Social Security tax wage. The latter is calculated under the assumption that there was zero tax in 1980 and a 30 percent tax in 2018. (These are intended to be extreme assumptions.) Even in this case the average after-Social Security tax wage in 2018 would still be 15 times as high as the wage in 1980.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

Of course in China, as with the United States, there has been an upward redistribution of income associated with a huge shift from wages to profits. As a result workers have not fully shared in the gains from growth over this period. But the limit in the gains to workers is clearly this distributional shift, not a deterioration in the country’s demographic picture.

In short, we have a seriously flawed scare story. The upward redistribution of income does pose a serious threat to the well-being of future generations of workers in the United States and elsewhere. The rise in the ratio of retirees to workers is not even an issue by comparison.

Do you remember back when we were worried that robots will take all of the jobs? There will be no work for any of us because we will have all been replaced by robots.

It turns out that we have even more to worry about. AP says that because of declining birth rates and increasing life expectancies, we face a huge demographic crunch. We will have hordes of retirees and no one to to do the work. Now that sounds really scary, at the same time we have no jobs because the robots took them we must also struggle with the fact that we have no one to do the work because everyone is old and retired.

Yes, these are the complete opposite arguments. It is possible for one or the other to be true, but only in Washington can both be problems simultaneously. In this case, I happen to be a good moderate and say that neither is true. There is no plausible story in which robots are going to make us all unemployed any time in the foreseeable future. Nor is there a case that the demographic will impoverish us.

The basic story is that we have a rising ratio of retirees to workers, which should promote outraged cries of “so what?” Yes folks, we have had rising ratios of retirees to workers for a long time. In 1960 there was just one retiree for every five workers. Today there is one retiree for every 2.8 workers, and the Social Security trustees tell us that in 2035 there will be one retiree for every 2.1 workers.

Source: Social Security Trustees Report.

Just as the fall in the ratio of workers to retirees between 1960 and 2013 did not prevent both workers and retirees from enjoying substantially higher living standards, there is no reason to expect the further decline in the ratio to 2035 to lead to a fall in living standards.

This point can be seen by comparing the average wage in 2013 with the average wage projected for 2035. The chart also includes the after-Social Security tax wage. The figure for 2035 assumes a 4.0 percentage point rise in the Social Security tax, an increase that is far larger than would be needed to keep the program fully funded under almost any conceivable circumstances. Even in this case, the average after tax wage would more than 38 percent higher than it is today.

Source: Social Security Trustees Report.

There is of course an issue of distribution. Most workers have not seen much benefit from the growth in average wages over the last three decades as most of the gains have gone to those at the top. But this points out yet again the urgency of addressing wage inequality. A continuing upward redistribution of income could make our children poor. Social Security and Medicare will not.

Finally, this AP article warns of the demographic nightmare facing China. Really?

China has seen incredible economic growth over the last three decades. As a result it is hugely richer today than it was in 1980. The chart below shows the ratio of real per capita income projected by the IMF for China in 2018 compared to its 1980 level. The projection for 2018 is more than 22 times as high as the 1980 level. The chart shows average wages under the assumption that wages grew in step with per capita income and a hypothetical after Social Security tax wage. The latter is calculated under the assumption that there was zero tax in 1980 and a 30 percent tax in 2018. (These are intended to be extreme assumptions.) Even in this case the average after-Social Security tax wage in 2018 would still be 15 times as high as the wage in 1980.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

Of course in China, as with the United States, there has been an upward redistribution of income associated with a huge shift from wages to profits. As a result workers have not fully shared in the gains from growth over this period. But the limit in the gains to workers is clearly this distributional shift, not a deterioration in the country’s demographic picture.

In short, we have a seriously flawed scare story. The upward redistribution of income does pose a serious threat to the well-being of future generations of workers in the United States and elsewhere. The rise in the ratio of retirees to workers is not even an issue by comparison.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

To the amazement of millions David Brooks had an interesting observation in his column today. He picked up an article by my friend Steve Teles which outlines the story of kludgeocracy.

Steve’s idea is that we often end up advancing policy goals in incredible indirect and inefficient ways because this is the only way to move forward. The Affordable Care Act could be the poster child for this point. We got an incredibly complicated and unnecessarily expensive system because the insurers, the drug companies, the medical equipment suppliers, and the doctors all pushed to ensure that they would get their cut of the pie on the way to getting closer to universal coverage.

Steve gives many other examples in this article. My personal favorite is flexible spending accounts, which allow people to squirrel away some amount of money on a pre-tax basis to pay for health care expenses, child care expenses, or work-related transportation expenses. The point is to have the federal government subsidize these activities.

The absurdity is that the payroll costs to employers for administering these accounts are often a substantial portion of the money being saved. A fee of $20 per employee would not be unusual. If that employee puts aside $1000 a year in an account and is in the 25 percent tax bracket, this implies the tax subsidy is a bit less than $400. (The money is also exempted from the payroll tax.) A $20 fee would imply that 5 percent of the savings are being eaten up in administrative costs.

In addition, the worker loses money not spent by the end of the year. This gives them an incentive to buy items not really needed (e.g. an extra pair of glasses) to avoid losing the money. Filling out the forms can also be very time-consuming for workers.

The shape of the subsidy is also awful from a distributional standpoint. Wealthier people stand to get the largest subsidies.

Of course the government could just subsidize health care directly, which would be far more efficient. But, all the people in the financial industry who make profits from managing flexible spending accounts would be very upset. Therefore we can expect these accounts to be around for some time. This is kludgeocracy.

To the amazement of millions David Brooks had an interesting observation in his column today. He picked up an article by my friend Steve Teles which outlines the story of kludgeocracy.

Steve’s idea is that we often end up advancing policy goals in incredible indirect and inefficient ways because this is the only way to move forward. The Affordable Care Act could be the poster child for this point. We got an incredibly complicated and unnecessarily expensive system because the insurers, the drug companies, the medical equipment suppliers, and the doctors all pushed to ensure that they would get their cut of the pie on the way to getting closer to universal coverage.

Steve gives many other examples in this article. My personal favorite is flexible spending accounts, which allow people to squirrel away some amount of money on a pre-tax basis to pay for health care expenses, child care expenses, or work-related transportation expenses. The point is to have the federal government subsidize these activities.

The absurdity is that the payroll costs to employers for administering these accounts are often a substantial portion of the money being saved. A fee of $20 per employee would not be unusual. If that employee puts aside $1000 a year in an account and is in the 25 percent tax bracket, this implies the tax subsidy is a bit less than $400. (The money is also exempted from the payroll tax.) A $20 fee would imply that 5 percent of the savings are being eaten up in administrative costs.

In addition, the worker loses money not spent by the end of the year. This gives them an incentive to buy items not really needed (e.g. an extra pair of glasses) to avoid losing the money. Filling out the forms can also be very time-consuming for workers.

The shape of the subsidy is also awful from a distributional standpoint. Wealthier people stand to get the largest subsidies.

Of course the government could just subsidize health care directly, which would be far more efficient. But, all the people in the financial industry who make profits from managing flexible spending accounts would be very upset. Therefore we can expect these accounts to be around for some time. This is kludgeocracy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That would have been a reasonable headline for a NYT article on India’s resistance to U.S.-type patent rights on expensive drugs. The focus of the piece is Herceptin, a cancer drug that costs $18,000 for a single round of treatment, which makes it unaffordable to almost anyone suffering from cancer in India. A generic version of this drug would likely cost two or three percent of this price.

As a result of the enormous price difference between patent protected drugs and free market drugs the Indian government is taking a very critical view of many patents. In this case, the manufacturer, Roche Holdings, has decided not to challenge the production of generics in Indian court since it believes it would lose the case.

The piece presents this issue as a problem because the widespread availability of low cost generics in India and elsewhere will reduce the returns to innovation and will mean that drug companies will have less incentive to invest in developing new drugs. While this is true if we rely exclusively on government granted monopolies to finance research, this is far from the only mechanism that could be or is used to finance research.

There are other more modern mechanisms for financing research than this relic from the feudal guild system. For example, Nobel laureate Joe Stiglitz has advocated a prize system whereby innovators are compensated for breakthroughs from a public prize fund and then the patent is placed in the public domain so that the drug can be freely produced as a generic. It is also possible to simply fund the research up front, as is already done to a substantial extent with the $30 billion a year provided to the National Institutes of Health.

If we eliminated monopolies it would both reduce the cost of drugs and also likely lead to better medicine. The enormous mark-ups provided by these government monopolies gives drug companies an incentive to mislead the public about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs. It is a standard practice to conceal or even misrepresent research findings (e.g. Vioxx). This leads to bad health outcomes, the cost of which likely exceeds the money invested in research and development by the drug companies by an order of magnitude.

For these reasons, a piece like this in the NYT should be highlighting the increasing difficulty that the United States and Europe are facing in imposing patent monopolies on prescription drugs in the developing world. It is wrong to imply that there is some inherent tension between affordable drugs and innovation. This tension only arises with the archaic patent system.

That would have been a reasonable headline for a NYT article on India’s resistance to U.S.-type patent rights on expensive drugs. The focus of the piece is Herceptin, a cancer drug that costs $18,000 for a single round of treatment, which makes it unaffordable to almost anyone suffering from cancer in India. A generic version of this drug would likely cost two or three percent of this price.

As a result of the enormous price difference between patent protected drugs and free market drugs the Indian government is taking a very critical view of many patents. In this case, the manufacturer, Roche Holdings, has decided not to challenge the production of generics in Indian court since it believes it would lose the case.

The piece presents this issue as a problem because the widespread availability of low cost generics in India and elsewhere will reduce the returns to innovation and will mean that drug companies will have less incentive to invest in developing new drugs. While this is true if we rely exclusively on government granted monopolies to finance research, this is far from the only mechanism that could be or is used to finance research.

There are other more modern mechanisms for financing research than this relic from the feudal guild system. For example, Nobel laureate Joe Stiglitz has advocated a prize system whereby innovators are compensated for breakthroughs from a public prize fund and then the patent is placed in the public domain so that the drug can be freely produced as a generic. It is also possible to simply fund the research up front, as is already done to a substantial extent with the $30 billion a year provided to the National Institutes of Health.

If we eliminated monopolies it would both reduce the cost of drugs and also likely lead to better medicine. The enormous mark-ups provided by these government monopolies gives drug companies an incentive to mislead the public about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs. It is a standard practice to conceal or even misrepresent research findings (e.g. Vioxx). This leads to bad health outcomes, the cost of which likely exceeds the money invested in research and development by the drug companies by an order of magnitude.

For these reasons, a piece like this in the NYT should be highlighting the increasing difficulty that the United States and Europe are facing in imposing patent monopolies on prescription drugs in the developing world. It is wrong to imply that there is some inherent tension between affordable drugs and innovation. This tension only arises with the archaic patent system.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Morning Edition picked up the theme of patent protection for prescription drugs providing a trade-off between affordability and innovation seen in the NYT today. This is an inaccurate description of the issues, since there are other more efficient mechanisms for financing research. The patent system for financing drug research both leads to bad health outcomes and is a substantial drag on growth and job creation since it pulls hundreds of billions of dollars out of consumers’ pockets every year. It would be good if NPR would stop getting the framing for such pieces from the drug industry.

Morning Edition picked up the theme of patent protection for prescription drugs providing a trade-off between affordability and innovation seen in the NYT today. This is an inaccurate description of the issues, since there are other more efficient mechanisms for financing research. The patent system for financing drug research both leads to bad health outcomes and is a substantial drag on growth and job creation since it pulls hundreds of billions of dollars out of consumers’ pockets every year. It would be good if NPR would stop getting the framing for such pieces from the drug industry.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s the calculation for those of you who didn’t know offhand whether $24 billion is a big deal to the federal government. It takes about two seconds to do this sort of calculation on CEPR’s nifty keep Responsible Budget Reporting Calculator.

That’s the calculation for those of you who didn’t know offhand whether $24 billion is a big deal to the federal government. It takes about two seconds to do this sort of calculation on CEPR’s nifty keep Responsible Budget Reporting Calculator.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Paul Sullivan gave NYT readers some pretty bizarre investment advice in his “Wealth Matters” column. He noted the Fed’s announcement that it would begin to cut back on its quantitative easing (QE) program, telling readers:

“Bonds are one area of concern. Since interest rates on fixed income, particularly benchmarks like 10-year United States Treasury notes, fell so much over the last few years, the view is they will begin to rise as the Fed ends its bond-buying program and the economy improves. As that happens, the value of bonds that people already own decreases.”

The problem with this story is that bond prices have already fallen, a lot. The yield on 10-year Treasury bonds fell as low as 1.5 percent last year. It is now at 3.0 percent. While it is possible, if not likely, that yields will rise further in the year ahead, the risk of big losses in value is much smaller now than it was in 2012.

The basic story here is a simple one. The markets anticipated the ending of QE and have largely incorporated it into bond prices. Other events could push bond yields higher and prices lower, but the ending of QE is not going to be one of them.

Note: Original said bond prices have risen — this was corrected.

Paul Sullivan gave NYT readers some pretty bizarre investment advice in his “Wealth Matters” column. He noted the Fed’s announcement that it would begin to cut back on its quantitative easing (QE) program, telling readers:

“Bonds are one area of concern. Since interest rates on fixed income, particularly benchmarks like 10-year United States Treasury notes, fell so much over the last few years, the view is they will begin to rise as the Fed ends its bond-buying program and the economy improves. As that happens, the value of bonds that people already own decreases.”

The problem with this story is that bond prices have already fallen, a lot. The yield on 10-year Treasury bonds fell as low as 1.5 percent last year. It is now at 3.0 percent. While it is possible, if not likely, that yields will rise further in the year ahead, the risk of big losses in value is much smaller now than it was in 2012.

The basic story here is a simple one. The markets anticipated the ending of QE and have largely incorporated it into bond prices. Other events could push bond yields higher and prices lower, but the ending of QE is not going to be one of them.

Note: Original said bond prices have risen — this was corrected.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a good piece explaining how some of the financial industry’s biggest defenders in academia are paid by the industry for their work.

The NYT had a good piece explaining how some of the financial industry’s biggest defenders in academia are paid by the industry for their work.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yes, the investigative team at the Washington Post is back on the trail. Today’s front page expose highlights a government program that uses 0.00008 percent of the federal budget to promote the health benefits of walnuts. The piece tells readers that this program is a “hard not to crack.” It explained that even though Representative Tom McClintock pushed to kill the program; Congress voted 322-98 to keep it, claiming that it provided benefits to farmers.

Of course this is not the only example of a wasteful program uncovered by the Post’s investigative team. They also highlight the “Christopher Columbus Fellowship Foundation,” a program that runs an essay contest for middle schoolers interested in science. This one takes up 0.00001 percent of the federal budget. Then we have the Lake Murray State Park Airport in Oklahoma on which the government wastes 0.000004 percent of its budget each year.

And, the Post reminds us of its earlier investigative work, like when it exposed the fact that 0.006 percent of Social Security benefits are sent to dead people in an earlier front page story. The Post adds to this that each month Social Security mistakenly identifies 0.00003 percent of its covered population as being dead even though they are still alive.

After going through a number of very small programs that the Post has decided are wasteful, the article implies that somehow spending has not actually been cut.

“Three years after deficit-driven Republicans took the House, Washington’s experiment with budget-cutting has produced mixed results. Politicians have, indeed, had historic success cutting numbers — the abstract, friend-less figures at the bottom of the federal balance sheet.

“In the next fiscal year, for instance, the government’s “discretionary” spending will be limited to $1.012 trillion. That figure was set by the budget deal agreed to last week. That’s down about 13 percent from 2010, adjusting for inflation.

“There has been very little change in ‘mandatory’ spending programs, which account for the vast majority of federal spending.”

Of course spending has actually been cut. The result has been that growth has been stunted. Hundreds of thousands more people are unemployed. This means that the spending cuts demanded by the Post in both its editorial and news sections has thrown the parents of our children out of work. These cuts have also made it much more difficult for young people just leaving school to find jobs.

The Post’s complaint about the fact that mandatory spending has not been cut reflects the fact that people across the political spectrum overwhelming support Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, as well as the other programs that account for the overwhelming majority of mandatory spending. The Post and its chosen sources, in this case the Concord Coalition, a Peter Peterson creation, are relatively lonely in pushing for cuts to these programs.

It is also worth noting that mandatory spending actually is now projected to be considerably lower as a result of a sharp slowdown in the rate of growth of health care costs. Spending for Medicare and Medicaid in 2020 is now projected to be about 10 percent less than was projected in 2010. The projected savings in later years are even larger.

Addendum:

I see from comments that some folks think it is appropriate to make a big deal about items that might be less than 0.0001 percent of the budget. That’s great if you want to spend your time on these relatively small amounts of spending, but it means that your efforts will have no noticeable impact on overall spending and deficits. If you want to have an impact on overall spending then you have spend your time on items that actually involve a big share of the budget. That’s just arithmetic.

My guess is that the vast majority of readers of the WaPo have no idea how insignificant the items it chose to highlight were to the overall budget because it never provided this information. Since most people have relatively little time to concern themselves with such issues, my guess is that they would rather focus on items that actually do have a noticeable impact on spending and deficits rather ones that the paper chose to highlight in an effort to make the government seem wasteful.

Correction made on projections for Medicare, thanks ltr.

Yes, the investigative team at the Washington Post is back on the trail. Today’s front page expose highlights a government program that uses 0.00008 percent of the federal budget to promote the health benefits of walnuts. The piece tells readers that this program is a “hard not to crack.” It explained that even though Representative Tom McClintock pushed to kill the program; Congress voted 322-98 to keep it, claiming that it provided benefits to farmers.

Of course this is not the only example of a wasteful program uncovered by the Post’s investigative team. They also highlight the “Christopher Columbus Fellowship Foundation,” a program that runs an essay contest for middle schoolers interested in science. This one takes up 0.00001 percent of the federal budget. Then we have the Lake Murray State Park Airport in Oklahoma on which the government wastes 0.000004 percent of its budget each year.

And, the Post reminds us of its earlier investigative work, like when it exposed the fact that 0.006 percent of Social Security benefits are sent to dead people in an earlier front page story. The Post adds to this that each month Social Security mistakenly identifies 0.00003 percent of its covered population as being dead even though they are still alive.

After going through a number of very small programs that the Post has decided are wasteful, the article implies that somehow spending has not actually been cut.

“Three years after deficit-driven Republicans took the House, Washington’s experiment with budget-cutting has produced mixed results. Politicians have, indeed, had historic success cutting numbers — the abstract, friend-less figures at the bottom of the federal balance sheet.

“In the next fiscal year, for instance, the government’s “discretionary” spending will be limited to $1.012 trillion. That figure was set by the budget deal agreed to last week. That’s down about 13 percent from 2010, adjusting for inflation.

“There has been very little change in ‘mandatory’ spending programs, which account for the vast majority of federal spending.”

Of course spending has actually been cut. The result has been that growth has been stunted. Hundreds of thousands more people are unemployed. This means that the spending cuts demanded by the Post in both its editorial and news sections has thrown the parents of our children out of work. These cuts have also made it much more difficult for young people just leaving school to find jobs.

The Post’s complaint about the fact that mandatory spending has not been cut reflects the fact that people across the political spectrum overwhelming support Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, as well as the other programs that account for the overwhelming majority of mandatory spending. The Post and its chosen sources, in this case the Concord Coalition, a Peter Peterson creation, are relatively lonely in pushing for cuts to these programs.

It is also worth noting that mandatory spending actually is now projected to be considerably lower as a result of a sharp slowdown in the rate of growth of health care costs. Spending for Medicare and Medicaid in 2020 is now projected to be about 10 percent less than was projected in 2010. The projected savings in later years are even larger.

Addendum:

I see from comments that some folks think it is appropriate to make a big deal about items that might be less than 0.0001 percent of the budget. That’s great if you want to spend your time on these relatively small amounts of spending, but it means that your efforts will have no noticeable impact on overall spending and deficits. If you want to have an impact on overall spending then you have spend your time on items that actually involve a big share of the budget. That’s just arithmetic.

My guess is that the vast majority of readers of the WaPo have no idea how insignificant the items it chose to highlight were to the overall budget because it never provided this information. Since most people have relatively little time to concern themselves with such issues, my guess is that they would rather focus on items that actually do have a noticeable impact on spending and deficits rather ones that the paper chose to highlight in an effort to make the government seem wasteful.

Correction made on projections for Medicare, thanks ltr.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had a good investigative piece on how for profit hospice-care providers are increasing their profits by admitting people for hospice care who are not actually dying. These people are far more profitable for the companies since they are likely to be receiving hospice care for a longer period of time and require less care than someone who is actually dying. Medicare and Medicaid pick up most of the cost of this care.

In the accounts of spending on the elderly that the Washington Post and others routinely cite to make arguments about generational inequity, the money ripped-off from the government by these hospice providers count as payments to the elderly.

The Washington Post had a good investigative piece on how for profit hospice-care providers are increasing their profits by admitting people for hospice care who are not actually dying. These people are far more profitable for the companies since they are likely to be receiving hospice care for a longer period of time and require less care than someone who is actually dying. Medicare and Medicaid pick up most of the cost of this care.

In the accounts of spending on the elderly that the Washington Post and others routinely cite to make arguments about generational inequity, the money ripped-off from the government by these hospice providers count as payments to the elderly.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Morning Edition had a segment on the Trans-Pacific Partnership and EU-U.S. trade agreement today. The piece began with a speech by President Obama in which he asserted that exports have been one of the fastest growing sectors of the economy. This is not true in any meaningful sense.

What matters for the economy is net exports, not exports alone. If GM shuts down an auto assembly plant in Ohio and replaces it with one in Mexico, which then ships the cars back to the United States, this would show up as an increase in exports. However, it would be associated with a loss of jobs and output in the United States since it means that imports will have grown by even more.

Much of our trade has this character. If we look at net exports, trade has actually been a drag on growth in 2013. Presumably President Obama understands this fact and was simply trying to deceive his audience to promote his trade agenda. NPR should have exposed this deception rather than assisting President Obama in accomplishing this goal.

The piece also repeatedly refers to these deals as “free trade” agreements. This is inaccurate. Many of the provisions in the proposed agreements have little to do with trade, as was explained in the segment, and some will actually increase barriers, as is the case with rules that will lead to strengthened copyright and patent protection.

Morning Edition had a segment on the Trans-Pacific Partnership and EU-U.S. trade agreement today. The piece began with a speech by President Obama in which he asserted that exports have been one of the fastest growing sectors of the economy. This is not true in any meaningful sense.

What matters for the economy is net exports, not exports alone. If GM shuts down an auto assembly plant in Ohio and replaces it with one in Mexico, which then ships the cars back to the United States, this would show up as an increase in exports. However, it would be associated with a loss of jobs and output in the United States since it means that imports will have grown by even more.

Much of our trade has this character. If we look at net exports, trade has actually been a drag on growth in 2013. Presumably President Obama understands this fact and was simply trying to deceive his audience to promote his trade agenda. NPR should have exposed this deception rather than assisting President Obama in accomplishing this goal.

The piece also repeatedly refers to these deals as “free trade” agreements. This is inaccurate. Many of the provisions in the proposed agreements have little to do with trade, as was explained in the segment, and some will actually increase barriers, as is the case with rules that will lead to strengthened copyright and patent protection.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión