• Economic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperaciónEconomic PolicyInflationUnited StatesEE. UU.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Economic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperaciónIntellectual PropertyPropiedad IntelectualUnited StatesEE. UU.

The standard line in policy circles about the soaring inequality of the last four decades is that it is just an unfortunate outcome of technological change. As a result of technological developments, education is much more highly valued and physical labor has much less value. The drop in relative income for workers without college degrees is unfortunate and provides grounds for lots of hand wringing and bloviating in elite media outlets, but hey, what can you do?

Manufacturing plays a central role in this story since it has historically been the major source of high-paying jobs for workers without college degrees. Manufacturing jobs offered a pay premium of almost 17.0 percent in the 1980s. This had fallen sharply by the start of the last decade and had largely disappeared in more recent years.

This decline in the wage premium has coincided with a plunge in unionization rates in manufacturing. Approximately 20 percent of manufacturing workers were unionized at the start of the 1980s. In 2021 just 7.7 percent of manufacturing workers were in unions, only slightly higher than the average of 6.1 percent in the private sector.

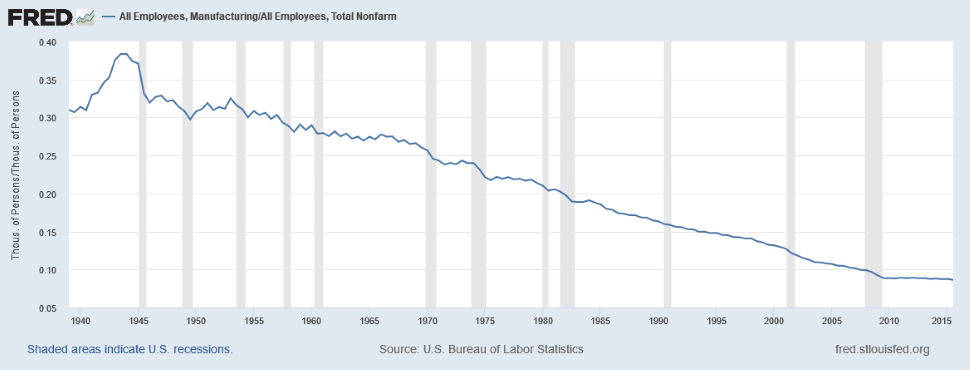

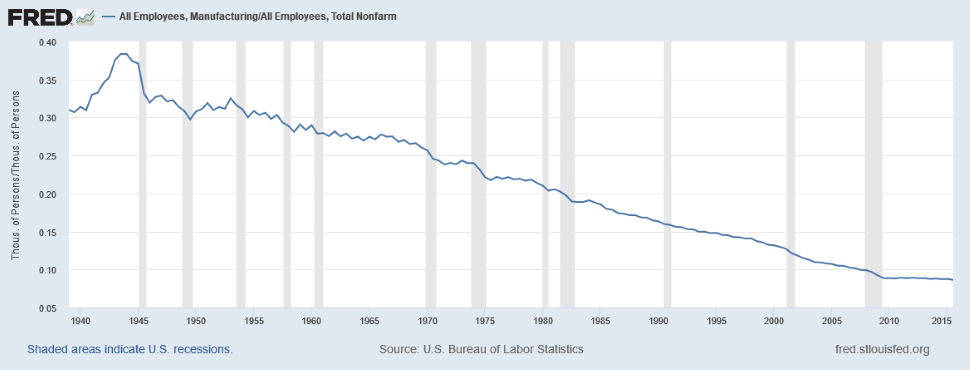

The media endlessly hits us with the line that this is just an unfortunate outcome of technological progress. Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell gives us the latest rendition this morning. The highlight is this graph showing that manufacturing had been seeing a steady decline in employment shares for the six decades from 1950 to 2010.

This is the basic “nothing to see here” story.

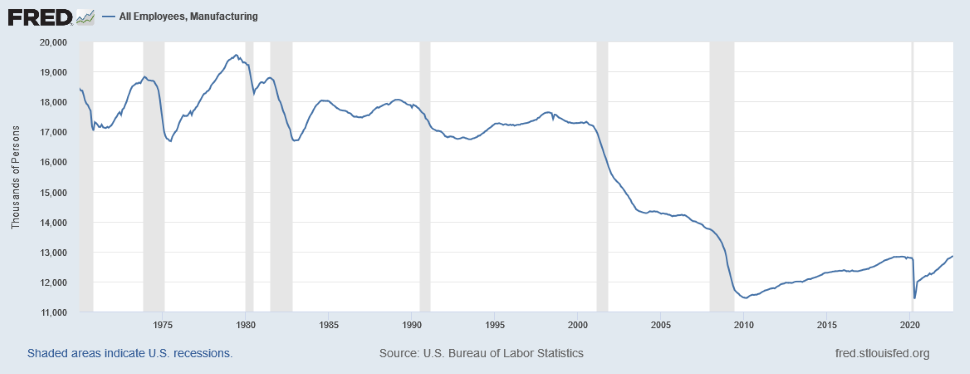

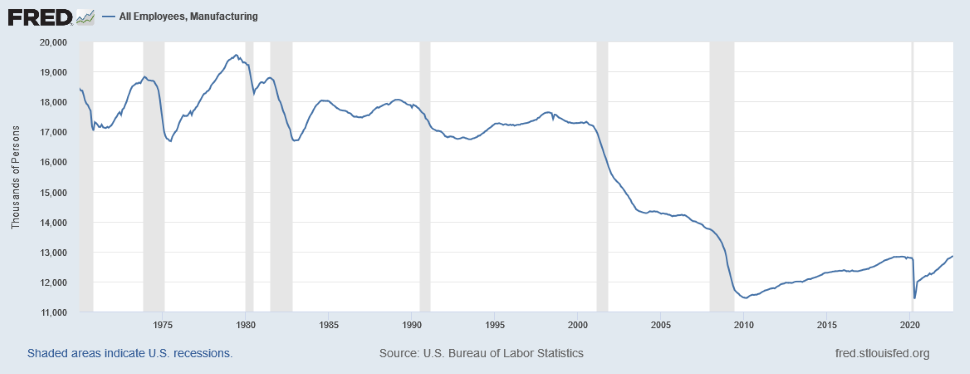

There is another graph that shows a very different story. The chart below shows employment in manufacturing not as a share of total employment but in absolute numbers. This one gives a very different picture.

From the start of 1970 to the middle of 1998, manufacturing employment has only a modest decline. There are cyclical ups and downs, but total job loss over this 28-year period was about 800,000, from 18.4 million in 1970 to 17.6 million in 1998, a decline of 4.4 percent.

However, the story becomes very different over the next decade. From the middle of 1998 to December of 2007, manufacturing lost almost 4 million jobs. This means that, after seeing a drop in employment of just 4.4 percent over 28 years, manufacturing saw a decline in employment of more than 22 percent in less than a decade. That looks like there is something to see here. (It lost another 2 million jobs in the Great Recession, which began in December 2007.)

The item to see in this graph is the explosion in the trade deficit in this decade, with the deficit on goods peaking at more than 6.0 percent of GDP during this period. In short, a huge increase in the trade deficit coincided with a massive and unprecedented loss in manufacturing jobs. Can we hear again how those workers are stupid for blaming trade for their problems?

It Took More than Trade to Screw the Country’s Workers

But trade is not the whole story of the upward redistribution of the last decade. We also made government-granted patent and copyright monopolies longer and stronger. We also encouraged the financial sector to become bloated, giving big paychecks to Wall Street types at the expense of the rest of us. And, we have a corrupt corporate governance structure that allows CEOs and other top management to line their pockets and rip off the companies they work for. And we also ensured that highly paid professionals, like doctors and dentists, are protected from the same competition that their less educated counterparts face.

This is the topic of Rigged [it’s free]. It’s also the focus of a video series I recently did with the Institute for New Economic Thinking, How to Unf*ck America. (Coming soon to a theater near you.)

Perhaps what is most striking about the inequality just happened story is how deeply ingrained it is among people in policy circles. When we make policy decisions that are virtually guaranteed to redistribute income upward, the implications for inequality do not even get raised.

The government paid Moderna $450 million to develop a coronavirus vaccine at the start of the pandemic, and it then spent another $450 million for its large-scale phase 3 testing. We then gave Moderna control over the intellectual property associated with the vaccine, and the result was that we got at least five Moderna billionaires.

More recently, Congress passed the CHIPS Act, which will involve tens of billions of dollars of subsidies to manufacturers of semiconductors and other cutting-edge products. Again, there seems to have been no debate about who will own the intellectual property.

Naturally, it will be the companies that get the contracts. This is like paying a company to build a factory and then letting them keep the factory. Oh well, as a consolation prize, we will get more opportunities for rich liberals to whine about inequality.

Rampell’s colleague, Andrew Van Dam, had a piece a couple of weeks back that inadvertently showed how inequality is taken for granted in policy circles. The highlight was where Van Dam gave us the “optimistic” view of how the increased globalization of many higher-end jobs (jobs where people can work remotely) would turn out.

“Many economists are optimistic that American workers will land on their feet amid a gradual transition from a world in which they compete with a few dozen locals for each new job to one in which they compete with a few million professionals worldwide. But economists were optimistic about Y2K-era globalization as well, and it seems wise to keep a wary eye on the possible downside.”

Okay, let’s get our eyes on the ball here. How is it “optimistic” that the pay of more educated workers is not depressed due to international competition, as when their less-educated counterparts were subjected to international competition with low-cost labor?

As Rampell rightly points out in her piece, protecting domestic manufacturing means higher prices for manufactured goods. These higher prices are paid by everyone, which is a bad story when it comes to getting people to buy electric cars and solar panels. Getting these items from lower-cost labor, whether from foreign sources, or domestic labor that has to take pay cuts due to competition, is good for consumers.

So why wouldn’t Van Dam see it as an optimistic story that we can get everything from accounting and legal services to medical consulting at a much lower cost due to increased international competition? Sure, our accountants, lawyers, and doctors would get lower pay, but this will mean lower consumer prices and more economic growth. How could any self-respecting policy wonk see this as a bad thing?

As a practical matter, I am sympathetic to many of the points Rampell makes. Since the manufacturing wage premium has largely disappeared, it doesn’t make sense to put a major focus on getting back manufacturing jobs. (The politics may argue otherwise.)

But, if we want to improve the situation of less-educated workers in our economy, we have to reverse how we have structured the market to redistribute so much income upward. Unfortunately, this topic is largely not considered suitable for discussion in the Washington Post and other elite media outlets.

The standard line in policy circles about the soaring inequality of the last four decades is that it is just an unfortunate outcome of technological change. As a result of technological developments, education is much more highly valued and physical labor has much less value. The drop in relative income for workers without college degrees is unfortunate and provides grounds for lots of hand wringing and bloviating in elite media outlets, but hey, what can you do?

Manufacturing plays a central role in this story since it has historically been the major source of high-paying jobs for workers without college degrees. Manufacturing jobs offered a pay premium of almost 17.0 percent in the 1980s. This had fallen sharply by the start of the last decade and had largely disappeared in more recent years.

This decline in the wage premium has coincided with a plunge in unionization rates in manufacturing. Approximately 20 percent of manufacturing workers were unionized at the start of the 1980s. In 2021 just 7.7 percent of manufacturing workers were in unions, only slightly higher than the average of 6.1 percent in the private sector.

The media endlessly hits us with the line that this is just an unfortunate outcome of technological progress. Washington Post columnist Catherine Rampell gives us the latest rendition this morning. The highlight is this graph showing that manufacturing had been seeing a steady decline in employment shares for the six decades from 1950 to 2010.

This is the basic “nothing to see here” story.

There is another graph that shows a very different story. The chart below shows employment in manufacturing not as a share of total employment but in absolute numbers. This one gives a very different picture.

From the start of 1970 to the middle of 1998, manufacturing employment has only a modest decline. There are cyclical ups and downs, but total job loss over this 28-year period was about 800,000, from 18.4 million in 1970 to 17.6 million in 1998, a decline of 4.4 percent.

However, the story becomes very different over the next decade. From the middle of 1998 to December of 2007, manufacturing lost almost 4 million jobs. This means that, after seeing a drop in employment of just 4.4 percent over 28 years, manufacturing saw a decline in employment of more than 22 percent in less than a decade. That looks like there is something to see here. (It lost another 2 million jobs in the Great Recession, which began in December 2007.)

The item to see in this graph is the explosion in the trade deficit in this decade, with the deficit on goods peaking at more than 6.0 percent of GDP during this period. In short, a huge increase in the trade deficit coincided with a massive and unprecedented loss in manufacturing jobs. Can we hear again how those workers are stupid for blaming trade for their problems?

It Took More than Trade to Screw the Country’s Workers

But trade is not the whole story of the upward redistribution of the last decade. We also made government-granted patent and copyright monopolies longer and stronger. We also encouraged the financial sector to become bloated, giving big paychecks to Wall Street types at the expense of the rest of us. And, we have a corrupt corporate governance structure that allows CEOs and other top management to line their pockets and rip off the companies they work for. And we also ensured that highly paid professionals, like doctors and dentists, are protected from the same competition that their less educated counterparts face.

This is the topic of Rigged [it’s free]. It’s also the focus of a video series I recently did with the Institute for New Economic Thinking, How to Unf*ck America. (Coming soon to a theater near you.)

Perhaps what is most striking about the inequality just happened story is how deeply ingrained it is among people in policy circles. When we make policy decisions that are virtually guaranteed to redistribute income upward, the implications for inequality do not even get raised.

The government paid Moderna $450 million to develop a coronavirus vaccine at the start of the pandemic, and it then spent another $450 million for its large-scale phase 3 testing. We then gave Moderna control over the intellectual property associated with the vaccine, and the result was that we got at least five Moderna billionaires.

More recently, Congress passed the CHIPS Act, which will involve tens of billions of dollars of subsidies to manufacturers of semiconductors and other cutting-edge products. Again, there seems to have been no debate about who will own the intellectual property.

Naturally, it will be the companies that get the contracts. This is like paying a company to build a factory and then letting them keep the factory. Oh well, as a consolation prize, we will get more opportunities for rich liberals to whine about inequality.

Rampell’s colleague, Andrew Van Dam, had a piece a couple of weeks back that inadvertently showed how inequality is taken for granted in policy circles. The highlight was where Van Dam gave us the “optimistic” view of how the increased globalization of many higher-end jobs (jobs where people can work remotely) would turn out.

“Many economists are optimistic that American workers will land on their feet amid a gradual transition from a world in which they compete with a few dozen locals for each new job to one in which they compete with a few million professionals worldwide. But economists were optimistic about Y2K-era globalization as well, and it seems wise to keep a wary eye on the possible downside.”

Okay, let’s get our eyes on the ball here. How is it “optimistic” that the pay of more educated workers is not depressed due to international competition, as when their less-educated counterparts were subjected to international competition with low-cost labor?

As Rampell rightly points out in her piece, protecting domestic manufacturing means higher prices for manufactured goods. These higher prices are paid by everyone, which is a bad story when it comes to getting people to buy electric cars and solar panels. Getting these items from lower-cost labor, whether from foreign sources, or domestic labor that has to take pay cuts due to competition, is good for consumers.

So why wouldn’t Van Dam see it as an optimistic story that we can get everything from accounting and legal services to medical consulting at a much lower cost due to increased international competition? Sure, our accountants, lawyers, and doctors would get lower pay, but this will mean lower consumer prices and more economic growth. How could any self-respecting policy wonk see this as a bad thing?

As a practical matter, I am sympathetic to many of the points Rampell makes. Since the manufacturing wage premium has largely disappeared, it doesn’t make sense to put a major focus on getting back manufacturing jobs. (The politics may argue otherwise.)

But, if we want to improve the situation of less-educated workers in our economy, we have to reverse how we have structured the market to redistribute so much income upward. Unfortunately, this topic is largely not considered suitable for discussion in the Washington Post and other elite media outlets.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Economic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperación

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post ran a piece last week that raised the possibility that workers who are now working remotely may see their jobs outsourced to countries with lower-cost labor. It raised the possibility that this might lead to the same sort of hit to jobs and wages that the rise in imports from China and elsewhere gave to manufacturing workers.

The piece then tells readers:

“Many economists are optimistic that American workers will land on their feet amid a gradual transition from a world in which they compete with a few dozen locals for each new job to one in which they compete with a few million professionals worldwide. But economists were optimistic about Y2K-era globalization as well, and it seems wise to keep a wary eye on the possible downside.”

While the second part of this paragraph is certainly true, most economists were very willing to ignore economics in arguing that massive imports from developing countries would not reduce the pay of manufacturing workers, and less educated workers more generally, the first sentence is a bit bizarre.

Exposing manufacturing workers to competition with their much lower-paid counterparts in the developing world is a big part of the upward redistribution of the last four decades. This had the effect of both lowering the pay of less-educated workers, and reducing the cost in the United States of a wide range of goods, from shoes and clothes, to cars and steel.

More educated workers were the beneficiaries of this reduction in costs. While their wages were not hurt by foreign competition, since they were largely protected, their money went further since they could now buy goods at a lower cost.

In this context, it is hard to imagine why anyone would consider it “optimistic” that the pay of more educated workers, who are now working remotely, will not be lowered by international competition. Such a reduction in pay should mean that a wide range of services, such as accounting, legal services, and medical services, can be provided at lower costs. This will benefit the whole country, but especially those workers who are not seeing their pay cut as a result of this competition.

The reduction in pay for more highly educated workers should also help reduce inflationary pressure in the economy. The highest 10 percent of the population takes in almost 50 percent of personal income. If we can reduce this by just 5 percent, this would be equal to 2.5 percent of total income.

To understand the economic importance of this sort of hit to the income of high-end earners, remember that many economists were going hysterical about the inflationary impact of President Biden’s student loan forgiveness program. By most estimates, loan forgiveness will reduce the amount that people are paying on student loans by roughly 0.1 percent of GDP.

This means that a 5 percent reduction in the pay of high-end earners would have 25 times as much impact in lowering inflation as the student loan forgiveness had in raising inflation. If people think student loan forgiveness is a big deal in raising inflation, then they should think that the prospect of international competition for remote workers will be an enormous deal in lowering inflation. Now, isn’t that optimistic?

Let me just add that I know that not all the people who will be hurt by increased competition for remote workers are rich. But, as the old saying goes, if you think you have a policy that does something useful, without harming some people you don’t want to see harmed, you don’t understand the policy. There is no way to lower incomes at the top without hitting some people who are not at the top.

Having said that, we can and should also pursue policies that are more directly focused on the very top, such as lowering CEO pay and eliminating the bloat in the financial sector. But if you show me a policy whose impact will be primarily to lower the pay of the top 20 percent of the workforce, I’m an optimist and I’m for it. I’d love to hear from those economists who say this is bad.

The Washington Post ran a piece last week that raised the possibility that workers who are now working remotely may see their jobs outsourced to countries with lower-cost labor. It raised the possibility that this might lead to the same sort of hit to jobs and wages that the rise in imports from China and elsewhere gave to manufacturing workers.

The piece then tells readers:

“Many economists are optimistic that American workers will land on their feet amid a gradual transition from a world in which they compete with a few dozen locals for each new job to one in which they compete with a few million professionals worldwide. But economists were optimistic about Y2K-era globalization as well, and it seems wise to keep a wary eye on the possible downside.”

While the second part of this paragraph is certainly true, most economists were very willing to ignore economics in arguing that massive imports from developing countries would not reduce the pay of manufacturing workers, and less educated workers more generally, the first sentence is a bit bizarre.

Exposing manufacturing workers to competition with their much lower-paid counterparts in the developing world is a big part of the upward redistribution of the last four decades. This had the effect of both lowering the pay of less-educated workers, and reducing the cost in the United States of a wide range of goods, from shoes and clothes, to cars and steel.

More educated workers were the beneficiaries of this reduction in costs. While their wages were not hurt by foreign competition, since they were largely protected, their money went further since they could now buy goods at a lower cost.

In this context, it is hard to imagine why anyone would consider it “optimistic” that the pay of more educated workers, who are now working remotely, will not be lowered by international competition. Such a reduction in pay should mean that a wide range of services, such as accounting, legal services, and medical services, can be provided at lower costs. This will benefit the whole country, but especially those workers who are not seeing their pay cut as a result of this competition.

The reduction in pay for more highly educated workers should also help reduce inflationary pressure in the economy. The highest 10 percent of the population takes in almost 50 percent of personal income. If we can reduce this by just 5 percent, this would be equal to 2.5 percent of total income.

To understand the economic importance of this sort of hit to the income of high-end earners, remember that many economists were going hysterical about the inflationary impact of President Biden’s student loan forgiveness program. By most estimates, loan forgiveness will reduce the amount that people are paying on student loans by roughly 0.1 percent of GDP.

This means that a 5 percent reduction in the pay of high-end earners would have 25 times as much impact in lowering inflation as the student loan forgiveness had in raising inflation. If people think student loan forgiveness is a big deal in raising inflation, then they should think that the prospect of international competition for remote workers will be an enormous deal in lowering inflation. Now, isn’t that optimistic?

Let me just add that I know that not all the people who will be hurt by increased competition for remote workers are rich. But, as the old saying goes, if you think you have a policy that does something useful, without harming some people you don’t want to see harmed, you don’t understand the policy. There is no way to lower incomes at the top without hitting some people who are not at the top.

Having said that, we can and should also pursue policies that are more directly focused on the very top, such as lowering CEO pay and eliminating the bloat in the financial sector. But if you show me a policy whose impact will be primarily to lower the pay of the top 20 percent of the workforce, I’m an optimist and I’m for it. I’d love to hear from those economists who say this is bad.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Economic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperaciónIntellectual PropertyPropiedad Intelectual

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Intellectual PropertyPropiedad Intelectual

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Economic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperación

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Economic PolicyInequalityLa DesigualdadUnited StatesEE. UU.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión