For all its many flaws Obamacare will prove to be a great thing for the simple reason that it will guarantee most of the population affordable health care insurance. The key group here is not the uninsured, many of whom will be able to get insurance as a result of the law, but rather the bulk of the under age 65 population whose insurance depends on their job. For the first time, these people will be in a situation where if they lose their job, they will still be able to get insurance they can afford. (Yes, I know that not everyone will find the insurance available through the exchanges affordable, hence the use of the word “most.”)

Anyhow, it is fascinating to see the continuing vitriole of the right against Obamacare, which is bearing ever less relationship to reality. We have heard endless talk about how Obamacare was creating a “part-time nation” as employers reduced work hours to get under the 30-hour cutoff for employer sanctions under the ACA. This one suffers from the problem that there were fewer people reported as working part-time at the end of 2013 than at the end of 2012. (Some of us are fans of voluntary part-time employment.)

Ed Rogers, writing in the Washington Post, told readers that the number of uninsured was rising because Target had stopped offering insurance to part-time workers. (Apart from the limited impact of the insurance status of Target’s part-time employees on national insurance rates, it is possible that Target stopped offering part-timers the option to buy into their insurance because few were taking it, given the expansion of Medicaid and the subsidies in the exchanges under the ACA.)

Wilson then linked to a “smart piece” by Megan McArdle which touted the imminent demise of Obamacare. Among the troubles of Obamacare cited by McArdle is that many of the people now signing up for Medicaid were already eligible before the ACA. This is an interesting claim, but so what if it is true? They previously had not been covered, now they are. And the problem is?

Another of the highlights is that the $2,500 in savings for a typical family has not materialized. Actually slower growth in health care costs have reduced spending by more than 10 percent compared to what was projected in 2008. That would translate into savings in the ballpark of $2,500 for a family of four. Clearly much of the slower cost growth was not due to the ACA, but does anyone doubt that if cost growth had accelerated it would be blamed on the ACA?

Anyhow, as the exchanges and Medicaid expansion become more a part of the health care framework, the ACA is going to gain increased acceptance even by Republicans, just as Medicare did. At some point, clever Republican politicians will recognize this fact and adjust their message to stay in line with their base. Meanwhile, the dead enders will get ever further removed from reality as they continue to push for the repeal of Obamacare.

For all its many flaws Obamacare will prove to be a great thing for the simple reason that it will guarantee most of the population affordable health care insurance. The key group here is not the uninsured, many of whom will be able to get insurance as a result of the law, but rather the bulk of the under age 65 population whose insurance depends on their job. For the first time, these people will be in a situation where if they lose their job, they will still be able to get insurance they can afford. (Yes, I know that not everyone will find the insurance available through the exchanges affordable, hence the use of the word “most.”)

Anyhow, it is fascinating to see the continuing vitriole of the right against Obamacare, which is bearing ever less relationship to reality. We have heard endless talk about how Obamacare was creating a “part-time nation” as employers reduced work hours to get under the 30-hour cutoff for employer sanctions under the ACA. This one suffers from the problem that there were fewer people reported as working part-time at the end of 2013 than at the end of 2012. (Some of us are fans of voluntary part-time employment.)

Ed Rogers, writing in the Washington Post, told readers that the number of uninsured was rising because Target had stopped offering insurance to part-time workers. (Apart from the limited impact of the insurance status of Target’s part-time employees on national insurance rates, it is possible that Target stopped offering part-timers the option to buy into their insurance because few were taking it, given the expansion of Medicaid and the subsidies in the exchanges under the ACA.)

Wilson then linked to a “smart piece” by Megan McArdle which touted the imminent demise of Obamacare. Among the troubles of Obamacare cited by McArdle is that many of the people now signing up for Medicaid were already eligible before the ACA. This is an interesting claim, but so what if it is true? They previously had not been covered, now they are. And the problem is?

Another of the highlights is that the $2,500 in savings for a typical family has not materialized. Actually slower growth in health care costs have reduced spending by more than 10 percent compared to what was projected in 2008. That would translate into savings in the ballpark of $2,500 for a family of four. Clearly much of the slower cost growth was not due to the ACA, but does anyone doubt that if cost growth had accelerated it would be blamed on the ACA?

Anyhow, as the exchanges and Medicaid expansion become more a part of the health care framework, the ACA is going to gain increased acceptance even by Republicans, just as Medicare did. At some point, clever Republican politicians will recognize this fact and adjust their message to stay in line with their base. Meanwhile, the dead enders will get ever further removed from reality as they continue to push for the repeal of Obamacare.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The mythical German economic boom, along with Santa Claus and the Loch Ness Monster, made an appearance in Roger Cohen’s NYT column this morning. (Actually, Santa is still recovering from his busy Christmas and Nessie is hiding, but the German boom is there, really.) Cohen tells readers that Germany did the right thing when its Social Democratic government weakened its welfare state. He now is pleased that France’s Socialist President Francois Hollande is about to follow suit.

“The German left partially dismantled the welfare state built by the German left. Unemployment fell, the economy boomed. Germany today is Germany and France is France.”

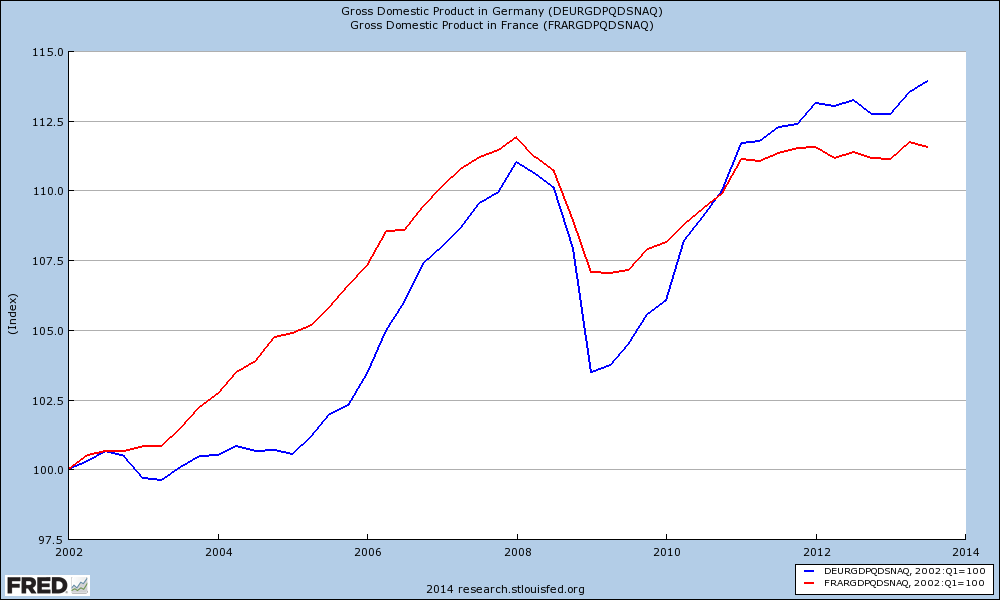

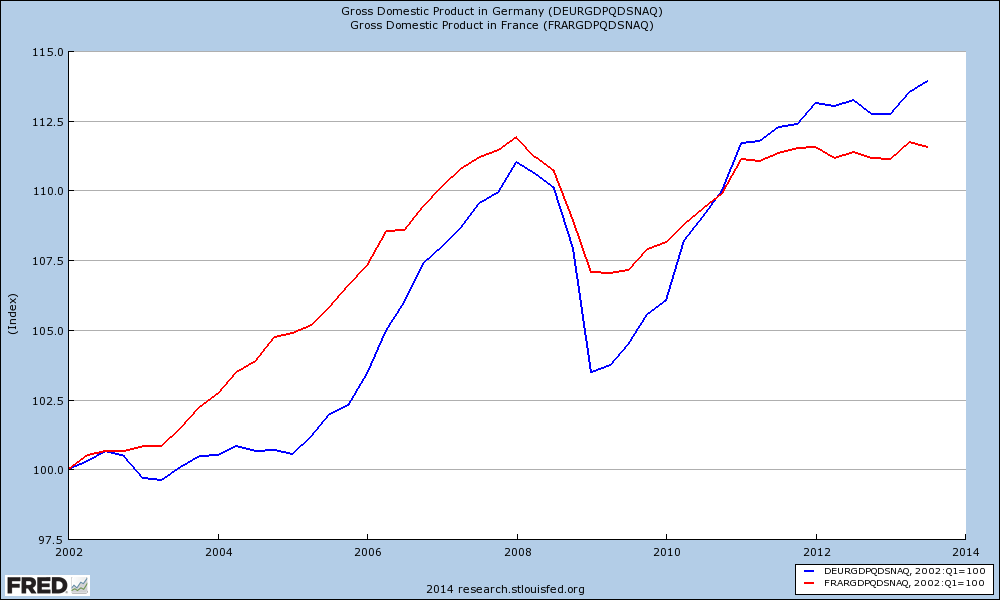

Let’s see, Germany boomed and France is France. Let’s check the score on that one. Here’s growth from 2002 to 2013 in the two countries. [I have corrected this to show more recent data, thanks Mark.]

Germany shows a hair more growth through the summer of 2013, but is a cumulative difference of 2.4 percentage points of growth over 11 years (0.2 percentage points a year) the difference between a booming economy and France? This is not trivial, but I’m not sure it is exactly the difference between a booming economy and a stagnant one. (The difference is somewhat larger in per capita terms. Germany’s population is shrinking slowly while France’s is growing. Some folks consider the latter a big positive, although I’m not in that camp. I have nothing against French people, but I don’t see how they are doing the world a service by producing more of them.)

While the difference in growth rates since Germany’s weakening of its welfare state may not justify Cohen’s celebration of a booming German economy, there is a notable difference in labor market outcomes. In the most recent data Germany has an unemployment rate of 5.2 percent while France has an unemployment rate of 10.8 percent.

This gap cannot be explained by the differences in growth rates in the two countries. Rather it stems from Germany’s aggressive use of work sharing and other policies designed to keep workers on the payroll even if it means a reduction in work hours. If Hollande wanted to copy a policy from Germany he might have looked to its success with work sharing. That policy has been far more successful in lowering unemployment than cuts in the welfare state have been in promoting growth.

Note: In response to comments, France is red, Germany is blue.

The mythical German economic boom, along with Santa Claus and the Loch Ness Monster, made an appearance in Roger Cohen’s NYT column this morning. (Actually, Santa is still recovering from his busy Christmas and Nessie is hiding, but the German boom is there, really.) Cohen tells readers that Germany did the right thing when its Social Democratic government weakened its welfare state. He now is pleased that France’s Socialist President Francois Hollande is about to follow suit.

“The German left partially dismantled the welfare state built by the German left. Unemployment fell, the economy boomed. Germany today is Germany and France is France.”

Let’s see, Germany boomed and France is France. Let’s check the score on that one. Here’s growth from 2002 to 2013 in the two countries. [I have corrected this to show more recent data, thanks Mark.]

Germany shows a hair more growth through the summer of 2013, but is a cumulative difference of 2.4 percentage points of growth over 11 years (0.2 percentage points a year) the difference between a booming economy and France? This is not trivial, but I’m not sure it is exactly the difference between a booming economy and a stagnant one. (The difference is somewhat larger in per capita terms. Germany’s population is shrinking slowly while France’s is growing. Some folks consider the latter a big positive, although I’m not in that camp. I have nothing against French people, but I don’t see how they are doing the world a service by producing more of them.)

While the difference in growth rates since Germany’s weakening of its welfare state may not justify Cohen’s celebration of a booming German economy, there is a notable difference in labor market outcomes. In the most recent data Germany has an unemployment rate of 5.2 percent while France has an unemployment rate of 10.8 percent.

This gap cannot be explained by the differences in growth rates in the two countries. Rather it stems from Germany’s aggressive use of work sharing and other policies designed to keep workers on the payroll even if it means a reduction in work hours. If Hollande wanted to copy a policy from Germany he might have looked to its success with work sharing. That policy has been far more successful in lowering unemployment than cuts in the welfare state have been in promoting growth.

Note: In response to comments, France is red, Germany is blue.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

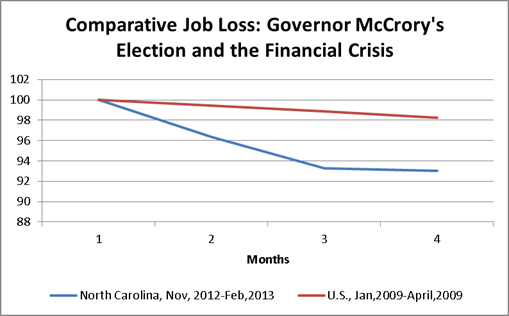

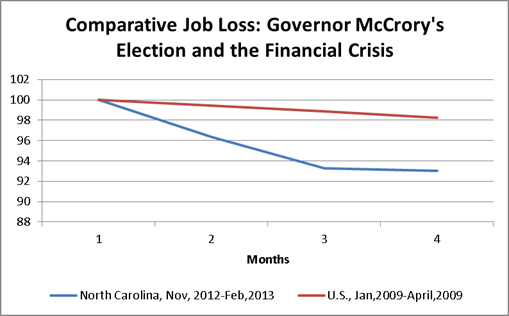

Brad Plummer calls our attention to a study by an economist at the University of Oslo showing that employment in North Carolina plummeted immediately following the election of Republican Governor Pat McCrory. According to the study, whose lead author is University of Oslo Professor Marcus Hagedorn, employment fell by 295,000 or 7.0 percent in the three months from November, 2012 to February, 2013. This plunge in employment was associated with a 5.3 percentage point drop in the employment to population ratio and a 6.3 percentage point decline in the labor force participation rate.

This falloff in employment is far sharper than even the worst period following the collapse of Lehman in 2008. In the worst three month period following the collapse the employment population ratio fell by just 1.1 percentage point, just over one-fifth of the drop seen following the election of Governor McCrory.

The plunge in North Carolina’s employment is especially striking since it came at time when the national economy was adding jobs at a respectable rate keeping the employment to population ratio nearly constant. Clearly businesses in North Carolina responded negatively to their new governor.

Actually, these data are directly taken from the Hagedorn paper (Table 1), but this is not a point that he makes in the paper. Instead, the paper claims that there was a sharp uptick in employment in the period since severe cuts in unemployment insurance benefit duration and eligibility were put in place in July of last year. While the data, which the authors have constructed from their analysis of the Current Population Survey, does show a sharp turnaround (which actually begins in February), it also shows this striking falloff in employment following the election.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Hagedorn, 2014.

In reality, this sharp falloff in employment almost certainly did not happen. This is horrific depression type stuff. Unless North Carolina was hit by some devastating epidemic, war, or climate disaster (the data are seasonally adjusted), employment could not have fallen as indicated in the data shown in the paper. Conversely, this also means that employment almost certainly did not rise as shown in the data. In other words, the data series in the paper is being moved by errors in measurement, not anything real in the economy.

The paper’s author obviously wants to argue that cutting unemployment benefits is a good thing for job creation and economic growth. His data are far too flimsy to make the case, which more reliable data clearly do not support. But if we want to treat the Hagedorn data as being authoritative then we can say that McCrory’s election was the worst thing to hit North Carolina since General Sherman’s army.

Note: Chart added and label corrected.

Brad Plummer calls our attention to a study by an economist at the University of Oslo showing that employment in North Carolina plummeted immediately following the election of Republican Governor Pat McCrory. According to the study, whose lead author is University of Oslo Professor Marcus Hagedorn, employment fell by 295,000 or 7.0 percent in the three months from November, 2012 to February, 2013. This plunge in employment was associated with a 5.3 percentage point drop in the employment to population ratio and a 6.3 percentage point decline in the labor force participation rate.

This falloff in employment is far sharper than even the worst period following the collapse of Lehman in 2008. In the worst three month period following the collapse the employment population ratio fell by just 1.1 percentage point, just over one-fifth of the drop seen following the election of Governor McCrory.

The plunge in North Carolina’s employment is especially striking since it came at time when the national economy was adding jobs at a respectable rate keeping the employment to population ratio nearly constant. Clearly businesses in North Carolina responded negatively to their new governor.

Actually, these data are directly taken from the Hagedorn paper (Table 1), but this is not a point that he makes in the paper. Instead, the paper claims that there was a sharp uptick in employment in the period since severe cuts in unemployment insurance benefit duration and eligibility were put in place in July of last year. While the data, which the authors have constructed from their analysis of the Current Population Survey, does show a sharp turnaround (which actually begins in February), it also shows this striking falloff in employment following the election.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Hagedorn, 2014.

In reality, this sharp falloff in employment almost certainly did not happen. This is horrific depression type stuff. Unless North Carolina was hit by some devastating epidemic, war, or climate disaster (the data are seasonally adjusted), employment could not have fallen as indicated in the data shown in the paper. Conversely, this also means that employment almost certainly did not rise as shown in the data. In other words, the data series in the paper is being moved by errors in measurement, not anything real in the economy.

The paper’s author obviously wants to argue that cutting unemployment benefits is a good thing for job creation and economic growth. His data are far too flimsy to make the case, which more reliable data clearly do not support. But if we want to treat the Hagedorn data as being authoritative then we can say that McCrory’s election was the worst thing to hit North Carolina since General Sherman’s army.

Note: Chart added and label corrected.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

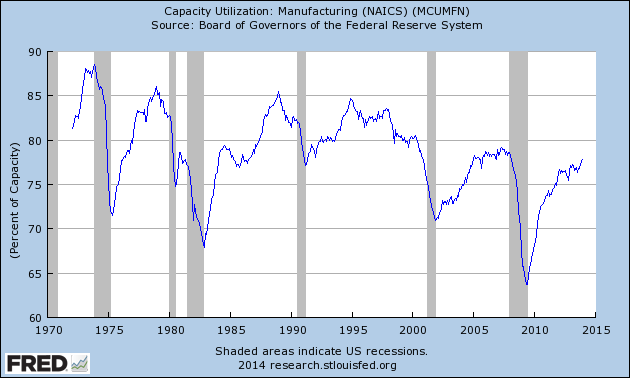

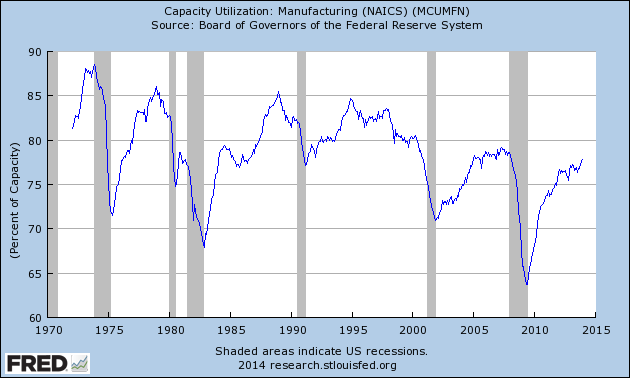

Actually the headline of the WSJ piece is “why hiring lags behind even as factories hum.” It then presents accounts of several companies putting off hiring and expansion plans because of uncertainty about the course of the economy. Several factory owners or managers report increasing the length of the workweek or investing in new technology as an alternative to new hiring.

While the anecdotes are interesting, the reality is that the main reason that firms are not hiring is that manufacturing is not humming. Capacity utilization rates are up from the recession troughs but at 77.8 percent are still below pre-recession levels, and far below the 82 percent plus range reached in the mid-1990s before a rising dollar led to a surge in the trade deficit and falling manufacturing employment.

The WSJ could have also discovered that its story that firms are turning to longer hours and capital investment as alternatives to hiring does not make sense by looking at data on hours and productivity growth in manufacturing. Neither show much support for its story. Average weekly hours are up very slightly compared to pre-recession levels or the mid-1990s, the last time there was consistent hiring in the sector, but the differences are small. The average workweek in 2013 was 41.9 hours, compared to 41.7 hours in 1997. The increase was entirely in non-durable manufacturing as there was a small drop in hours in durable goods manufacturing. And productivity growth has actually been relatively weak in recent years, going in the opposite direction as would be expected if firms were investing heavily to avoid hiring.

Productivity growth in manufacturing has averaged less than 2.0 percent in the last 3 years compared to an average of more than 4 percent in mid-1990s. It would have been useful for readers if the WSJ had taken advantage of government data instead of just talking to a small number of plant managers.

Actually the headline of the WSJ piece is “why hiring lags behind even as factories hum.” It then presents accounts of several companies putting off hiring and expansion plans because of uncertainty about the course of the economy. Several factory owners or managers report increasing the length of the workweek or investing in new technology as an alternative to new hiring.

While the anecdotes are interesting, the reality is that the main reason that firms are not hiring is that manufacturing is not humming. Capacity utilization rates are up from the recession troughs but at 77.8 percent are still below pre-recession levels, and far below the 82 percent plus range reached in the mid-1990s before a rising dollar led to a surge in the trade deficit and falling manufacturing employment.

The WSJ could have also discovered that its story that firms are turning to longer hours and capital investment as alternatives to hiring does not make sense by looking at data on hours and productivity growth in manufacturing. Neither show much support for its story. Average weekly hours are up very slightly compared to pre-recession levels or the mid-1990s, the last time there was consistent hiring in the sector, but the differences are small. The average workweek in 2013 was 41.9 hours, compared to 41.7 hours in 1997. The increase was entirely in non-durable manufacturing as there was a small drop in hours in durable goods manufacturing. And productivity growth has actually been relatively weak in recent years, going in the opposite direction as would be expected if firms were investing heavily to avoid hiring.

Productivity growth in manufacturing has averaged less than 2.0 percent in the last 3 years compared to an average of more than 4 percent in mid-1990s. It would have been useful for readers if the WSJ had taken advantage of government data instead of just talking to a small number of plant managers.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That’s what readers must be asking after seeing this piece discussing the prospects for fracking in Australia. The piece tell readers:

“Whereas about 1.5 million fracking jobs have taken place in the United States, only 2,500 have occurred in Australia, according to the Victoria report.”

It’s not clear where the NYT got the 1.5 million jobs figure, but it’s a safe bet that it is not from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The December, 2013 jobs figure for oil and gas extraction 48,400 higher than the December 2007 number, before the impact of both fracking and the recession. The figure for mining and support activities is up by 98,400. If we assume that this is all due to fracking then the total increase in employment is 146,800, less than one-tenth of the NYT’s number.

While there are undoubtedly some secondary effects from respending by workers in this sector and lower gas prices, if these are included then it would also be necessary to count the loss of jobs in the coal industry, clean energy and conservation sectors. There is no plausible story that could get from number of jobs in the sector reported by to the NYT’s 1.5 million.

It also would have been useful if this piece was more specific about the environmental issues raised in Australia. In the United States, firms engaged in fracking have a special exemption from the Safe Water Drinking Act which lets them keep secret the chemicals used in fracking. The exemption was justified on the grounds that the mix of chemicals used is an industrial secret. This makes it difficult to determine if they have polluted groundwater. It would be worth knowing if the same issue has come in Australia.

Correction:

I have been informed that “fracking jobs” refers to sites that have been fracked, not people employed. My guess is that a small fraction of NYT readers would have known this. As a result, the statement may well be true, but likely would have misled the vast majority of the people who read it.

That’s what readers must be asking after seeing this piece discussing the prospects for fracking in Australia. The piece tell readers:

“Whereas about 1.5 million fracking jobs have taken place in the United States, only 2,500 have occurred in Australia, according to the Victoria report.”

It’s not clear where the NYT got the 1.5 million jobs figure, but it’s a safe bet that it is not from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The December, 2013 jobs figure for oil and gas extraction 48,400 higher than the December 2007 number, before the impact of both fracking and the recession. The figure for mining and support activities is up by 98,400. If we assume that this is all due to fracking then the total increase in employment is 146,800, less than one-tenth of the NYT’s number.

While there are undoubtedly some secondary effects from respending by workers in this sector and lower gas prices, if these are included then it would also be necessary to count the loss of jobs in the coal industry, clean energy and conservation sectors. There is no plausible story that could get from number of jobs in the sector reported by to the NYT’s 1.5 million.

It also would have been useful if this piece was more specific about the environmental issues raised in Australia. In the United States, firms engaged in fracking have a special exemption from the Safe Water Drinking Act which lets them keep secret the chemicals used in fracking. The exemption was justified on the grounds that the mix of chemicals used is an industrial secret. This makes it difficult to determine if they have polluted groundwater. It would be worth knowing if the same issue has come in Australia.

Correction:

I have been informed that “fracking jobs” refers to sites that have been fracked, not people employed. My guess is that a small fraction of NYT readers would have known this. As a result, the statement may well be true, but likely would have misled the vast majority of the people who read it.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post gave front page coverage to some serious non-news when it highlighted a “landmark” study showing no substantial changes in mobility for children born in the early 1990s relative to children born in the early 1970s. While this findings is presented as surprising to both people who expected an increase or decrease in mobility, it really would have been surprising if the study had found otherwise.

The big shift in the income distribution against workers at the bottom occurred in the 1980s before the oldest people in this study entered the labor force. The upward redistribution in the period between when the oldest and youngest people in this study entered the labor force would have been primarily to the one percent. It would have been very surprising in a context where they are not big changes in the income distribution among the bottom four quintiles that there would be substantial changes in mobility.

It is probably useful that these researchers confirmed what most observers of the economy already believed, but it doesn’t seem like front page news.

The Washington Post gave front page coverage to some serious non-news when it highlighted a “landmark” study showing no substantial changes in mobility for children born in the early 1990s relative to children born in the early 1970s. While this findings is presented as surprising to both people who expected an increase or decrease in mobility, it really would have been surprising if the study had found otherwise.

The big shift in the income distribution against workers at the bottom occurred in the 1980s before the oldest people in this study entered the labor force. The upward redistribution in the period between when the oldest and youngest people in this study entered the labor force would have been primarily to the one percent. It would have been very surprising in a context where they are not big changes in the income distribution among the bottom four quintiles that there would be substantial changes in mobility.

It is probably useful that these researchers confirmed what most observers of the economy already believed, but it doesn’t seem like front page news.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Eduardo Porter asks how much the housing bubble and its collapse cost us in his column today. (He actually asks about the financial crisis, but this was secondary. The damage was caused by the loss of demand driven by bubble wealth in a context where we had nothing to replace it.) Porter throws out some estimates from different sources, but there are some fairly straightforward ways to get some numbers from authoritative sources.

We can use as a starting point the Congressional Budget Office’s projections for GDP growth from 2008, before it recognized the damage from the collapse of the bubble. We can then compare these projections with the most recent projections from last year.

If we just take the dollar losses through 2013 we get $7.6 trillion, in 2013 dollars. This is just economic losses, it does not include any effort to quantify the pain that workers or their families have suffered from being unemployed or losing their homes. This comes to roughly $25,000 for every person in the country. Alternatively, it is 190 times as much as the Republicans hoped to save from their cuts to food stamps over the next decade.

Many folks around Washington like to talk about 75 year numbers, which is the period over which we project Social Security and Medicare spending and revenue. If we assume that the economy’s growth rate in years after 2018 is not affected by the collapse of the bubble, then the cumulative loss in output through 2089 as a result of the collapse of the Greenspan-Rubin bubble would be $66.3 trillion. This amount is almost seven times the size of the projected Social Security shortfall.

If we really want to have fun, we can sum the shortfall over the infinite horizon, an accounting technique that is gaining popularity among those advocating cuts to Social Security and Medicare. The loss over the infinite horizon due to the Greenspan-Rubin bubble would be over $140 trillion, or more than $400,000 for every man, woman, and child in the country.

Obviously these numbers are very speculative but the basic story is very simple. If you want to have a big political battle in Washington, start yelling about people freeloading on food stamps, but if you actually care about where the real money is, look at the massive wreckage being done by the Wall Street boys and incompetent policy makers in Washington.

Eduardo Porter asks how much the housing bubble and its collapse cost us in his column today. (He actually asks about the financial crisis, but this was secondary. The damage was caused by the loss of demand driven by bubble wealth in a context where we had nothing to replace it.) Porter throws out some estimates from different sources, but there are some fairly straightforward ways to get some numbers from authoritative sources.

We can use as a starting point the Congressional Budget Office’s projections for GDP growth from 2008, before it recognized the damage from the collapse of the bubble. We can then compare these projections with the most recent projections from last year.

If we just take the dollar losses through 2013 we get $7.6 trillion, in 2013 dollars. This is just economic losses, it does not include any effort to quantify the pain that workers or their families have suffered from being unemployed or losing their homes. This comes to roughly $25,000 for every person in the country. Alternatively, it is 190 times as much as the Republicans hoped to save from their cuts to food stamps over the next decade.

Many folks around Washington like to talk about 75 year numbers, which is the period over which we project Social Security and Medicare spending and revenue. If we assume that the economy’s growth rate in years after 2018 is not affected by the collapse of the bubble, then the cumulative loss in output through 2089 as a result of the collapse of the Greenspan-Rubin bubble would be $66.3 trillion. This amount is almost seven times the size of the projected Social Security shortfall.

If we really want to have fun, we can sum the shortfall over the infinite horizon, an accounting technique that is gaining popularity among those advocating cuts to Social Security and Medicare. The loss over the infinite horizon due to the Greenspan-Rubin bubble would be over $140 trillion, or more than $400,000 for every man, woman, and child in the country.

Obviously these numbers are very speculative but the basic story is very simple. If you want to have a big political battle in Washington, start yelling about people freeloading on food stamps, but if you actually care about where the real money is, look at the massive wreckage being done by the Wall Street boys and incompetent policy makers in Washington.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Yep, that sounds like a true world crisis. And you can read about it right here in the NYT. The headline of the article tells readers that this year’s meeting of the world’s rich will focus on the aging of Asia’s population. As the piece explains:

“Asia’s aging has big implications globally. It ultimately means fewer workers and higher wages, adding to the cost of goods manufactured in Asia. And it could mean less dynamic growth in a region that is increasingly important to the world economy.”

Of course most of us value growth because it can increase living standards. This means things like higher wages, which translate into more income per person. Higher GDP that is simply due to more people, is not anything to be valued. (I’m open to a story if someone wants to give it.) And of course in a world where global warming is a huge problem facing the future, lower rates of population growth or population decline should be celebrated, not feared.

The piece also seems to get some of its basic numbers wrong. At one point it tells readers:

“Roughly 9 percent of Chinese, well over 110 million people, are now aged 65 or older. That percentage is only slightly below that in the United States. Moreover, it will rise to more than 16 percent by the end of the next decade, according to United Nations projections, meaning that by then China’s population will be roughly as old as Europe’s is now.”

Let’s see, 9 percent of China’s population is over age 65 and this is only slightly below the ratio in the United States? That’s not what the Social Security trustees say. The 2013 trustees report puts the total population in 2012 at 319.7 million. The over 65 population is listed at 43.6 million. This puts the share of the elderly at 13.6 percent. That’s more than 50 percent higher than share of 9 percent given for China in this article.

Typo corrected, thanks Joe.

Yep, that sounds like a true world crisis. And you can read about it right here in the NYT. The headline of the article tells readers that this year’s meeting of the world’s rich will focus on the aging of Asia’s population. As the piece explains:

“Asia’s aging has big implications globally. It ultimately means fewer workers and higher wages, adding to the cost of goods manufactured in Asia. And it could mean less dynamic growth in a region that is increasingly important to the world economy.”

Of course most of us value growth because it can increase living standards. This means things like higher wages, which translate into more income per person. Higher GDP that is simply due to more people, is not anything to be valued. (I’m open to a story if someone wants to give it.) And of course in a world where global warming is a huge problem facing the future, lower rates of population growth or population decline should be celebrated, not feared.

The piece also seems to get some of its basic numbers wrong. At one point it tells readers:

“Roughly 9 percent of Chinese, well over 110 million people, are now aged 65 or older. That percentage is only slightly below that in the United States. Moreover, it will rise to more than 16 percent by the end of the next decade, according to United Nations projections, meaning that by then China’s population will be roughly as old as Europe’s is now.”

Let’s see, 9 percent of China’s population is over age 65 and this is only slightly below the ratio in the United States? That’s not what the Social Security trustees say. The 2013 trustees report puts the total population in 2012 at 319.7 million. The over 65 population is listed at 43.6 million. This puts the share of the elderly at 13.6 percent. That’s more than 50 percent higher than share of 9 percent given for China in this article.

Typo corrected, thanks Joe.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Paul Krugman is a very smart person who does a fine job of defending himself. But he has enough detractors who repeat the same nonsense enough times that some reasonable people may actually be deceived.

For this reason, I will briefly intervene to point out that the people claiming Krugman called on Greenspan to create a housing bubble in 2002, like Bret Stephens in the Wall Street Journal today, are just making stuff up.

The basis for this absurd claim was a 2002 column on the weak recovery following the 2001 recession. The column notes the weakness of the economy at the time (we were still losing jobs 8 months after the official end of the recession) and attributes it to the fact that the 2001 recession was not a standard post-war recession. It was brought about by the collapse of the stock bubble.

Krugman then wrote:

“To fight this recession the Fed needs more than a snapback; it needs soaring household spending to offset moribund business investment. And to do that, as Paul McCulley of Pimco put it, Alan Greenspan needs to create a housing bubble to replace the Nasdaq bubble.”

It should have been pretty evident that this was sarcastic. Later in the piece, Krugman derides Greenspan for failing to have taken steps to head off the stock bubble, explaining that Greenspan badly needed a recovery:

“to avoid awkward questions about his own role in creating the stock market bubble.”

The last paragraph expresses Krugman’s pessimism about the recovery’s prospects:

“But wishful thinking aside, I just don’t understand the grounds for optimism. Who, exactly, is about to start spending a lot more? At this point it’s a lot easier to tell a story about how the recovery will stall than about how it will speed up. And while I like movies with happy endings as much as the next guy, a movie isn’t realistic unless the story line makes sense.”

Note, there is no moaning about how difficult it is to get a housing bubble going. The point was that we needed some additional source of demand and Krugman did not see where it would come from. In this respect, it is worth noting that two weeks later, partly at my prodding, Krugman wrote a column explicitly warning about the dangers of a housing bubble.

So let’s cut the crap. There are plenty of places that right-wingers should be able to take issue with what Krugman says, but the story about him urging Greenspan to create a housing bubble in 2002 is complete nonsense. The people who repeat this line are either dishonest or too clueless to take seriously.

Paul Krugman is a very smart person who does a fine job of defending himself. But he has enough detractors who repeat the same nonsense enough times that some reasonable people may actually be deceived.

For this reason, I will briefly intervene to point out that the people claiming Krugman called on Greenspan to create a housing bubble in 2002, like Bret Stephens in the Wall Street Journal today, are just making stuff up.

The basis for this absurd claim was a 2002 column on the weak recovery following the 2001 recession. The column notes the weakness of the economy at the time (we were still losing jobs 8 months after the official end of the recession) and attributes it to the fact that the 2001 recession was not a standard post-war recession. It was brought about by the collapse of the stock bubble.

Krugman then wrote:

“To fight this recession the Fed needs more than a snapback; it needs soaring household spending to offset moribund business investment. And to do that, as Paul McCulley of Pimco put it, Alan Greenspan needs to create a housing bubble to replace the Nasdaq bubble.”

It should have been pretty evident that this was sarcastic. Later in the piece, Krugman derides Greenspan for failing to have taken steps to head off the stock bubble, explaining that Greenspan badly needed a recovery:

“to avoid awkward questions about his own role in creating the stock market bubble.”

The last paragraph expresses Krugman’s pessimism about the recovery’s prospects:

“But wishful thinking aside, I just don’t understand the grounds for optimism. Who, exactly, is about to start spending a lot more? At this point it’s a lot easier to tell a story about how the recovery will stall than about how it will speed up. And while I like movies with happy endings as much as the next guy, a movie isn’t realistic unless the story line makes sense.”

Note, there is no moaning about how difficult it is to get a housing bubble going. The point was that we needed some additional source of demand and Krugman did not see where it would come from. In this respect, it is worth noting that two weeks later, partly at my prodding, Krugman wrote a column explicitly warning about the dangers of a housing bubble.

So let’s cut the crap. There are plenty of places that right-wingers should be able to take issue with what Krugman says, but the story about him urging Greenspan to create a housing bubble in 2002 is complete nonsense. The people who repeat this line are either dishonest or too clueless to take seriously.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT treated its readers to the French version of Le Grande Bargain, with a column by Sylvie Kauffman, the editorial director and former editor in chief of Le Monde. Ms. Kauffman’s piece, “the unbearable lightness of Hollande,” is devoted to the indecisiveness of the French president both in his policies and apparently in his personal life.

Her main complaint is:

“Perplexed by their president’s economic indecisiveness since he took office, the French now learn that he is equally indecisive in his private life. And they have found out at the worst moment. After hesitating to address squarely the issue of radical economic reforms, after avoiding to cut public spending to reduce the fiscal deficit, after procrastinating on measures needed to restore the competitiveness of French companies, the president, having lost 20 months, finally decided that it was time to do all of the above.”

Hmmm, Hollande put off Kauffman’s radical economic reforms and spending cuts for 20 months and this perplexed the French? Well if Hollande ran on an agenda of cutting social spending to go along with tax cuts, it certainly was not widely reported in the United States. I haven’t checked back issues of Le Monde (my French is mixed at best), but my guess is that Ms. Kauffman’s paper did not report any such commitments from Hollande either.

In fact, what was reported on Hollande’s campaign was a promise to break with austerity and to follow the precepts of modern economics. This means increasing deficits in a downturn, not cutting them. There is no evidence that the private sector will make up for the demand lost due to reductions in the deficit. In fact, there is now a large body of evidence, much of it produced by the International Monetary Fund, showing that the program demanded by Kauffman will lead to slower growth and more unemployment.

In effect, Kaufman is telling NYT readers that she finds it unbearable that a French president, who was elected on a platform going 180 degrees in the opposite direction, waited 20 months to embrace the economic policies that she favors; policies that have been shown to slow growth and raise unemployment.

Undoubtedly being the editorial director or editor in chief of Le Monde is a very important and prestigious position in France. Just as people like Peter Peterson and his fellow corporate chieftains in Fix the Debt feel that their policy perspectives should over-ride the views of the vast majority of the public and the state of knowledge in the economics profession, Ms. Kauffman feels the same way with respect to the French people.

I suppose elites everywhere never had much use for democracy or inconvenient truth. Get me some freedom fries.

The NYT treated its readers to the French version of Le Grande Bargain, with a column by Sylvie Kauffman, the editorial director and former editor in chief of Le Monde. Ms. Kauffman’s piece, “the unbearable lightness of Hollande,” is devoted to the indecisiveness of the French president both in his policies and apparently in his personal life.

Her main complaint is:

“Perplexed by their president’s economic indecisiveness since he took office, the French now learn that he is equally indecisive in his private life. And they have found out at the worst moment. After hesitating to address squarely the issue of radical economic reforms, after avoiding to cut public spending to reduce the fiscal deficit, after procrastinating on measures needed to restore the competitiveness of French companies, the president, having lost 20 months, finally decided that it was time to do all of the above.”

Hmmm, Hollande put off Kauffman’s radical economic reforms and spending cuts for 20 months and this perplexed the French? Well if Hollande ran on an agenda of cutting social spending to go along with tax cuts, it certainly was not widely reported in the United States. I haven’t checked back issues of Le Monde (my French is mixed at best), but my guess is that Ms. Kauffman’s paper did not report any such commitments from Hollande either.

In fact, what was reported on Hollande’s campaign was a promise to break with austerity and to follow the precepts of modern economics. This means increasing deficits in a downturn, not cutting them. There is no evidence that the private sector will make up for the demand lost due to reductions in the deficit. In fact, there is now a large body of evidence, much of it produced by the International Monetary Fund, showing that the program demanded by Kauffman will lead to slower growth and more unemployment.

In effect, Kaufman is telling NYT readers that she finds it unbearable that a French president, who was elected on a platform going 180 degrees in the opposite direction, waited 20 months to embrace the economic policies that she favors; policies that have been shown to slow growth and raise unemployment.

Undoubtedly being the editorial director or editor in chief of Le Monde is a very important and prestigious position in France. Just as people like Peter Peterson and his fellow corporate chieftains in Fix the Debt feel that their policy perspectives should over-ride the views of the vast majority of the public and the state of knowledge in the economics profession, Ms. Kauffman feels the same way with respect to the French people.

I suppose elites everywhere never had much use for democracy or inconvenient truth. Get me some freedom fries.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión