The media have been hyping inflation pretty much from the day President Biden took office. Today, we got great news on this front from a Consumer Price Index (CPI) report showing that overall inflation fell 0.1 percent in December. This is the 6th straight month where the overall CPI showed low inflation. While there are still grounds for concern, the picture looks pretty damn good at this point.

However, the media is not prepared to give up its inflation hysteria so quickly. The New York Times was on the job, raising some reasonable warning signs, then adding:

“Airline prices fell in December but remained nearly 29 percent higher compared with a year ago.”

While a 29 percent year over year increase might sound pretty scary, it’s actually not very scary to anyone who follows the data. Airline prices plummeted at the start of the pandemic, because people were not flying. They then bounced back more or less to where they had been before the pandemic. Here’s the picture.

CPI Index for Airfares: 2012 to 2022

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The CPI index for airfares in December was 0.7 percent higher than its level in February of 2020. That is probably not the sort of price increase that will get the Fed or anyone else too worried about inflation.

The media have been hyping inflation pretty much from the day President Biden took office. Today, we got great news on this front from a Consumer Price Index (CPI) report showing that overall inflation fell 0.1 percent in December. This is the 6th straight month where the overall CPI showed low inflation. While there are still grounds for concern, the picture looks pretty damn good at this point.

However, the media is not prepared to give up its inflation hysteria so quickly. The New York Times was on the job, raising some reasonable warning signs, then adding:

“Airline prices fell in December but remained nearly 29 percent higher compared with a year ago.”

While a 29 percent year over year increase might sound pretty scary, it’s actually not very scary to anyone who follows the data. Airline prices plummeted at the start of the pandemic, because people were not flying. They then bounced back more or less to where they had been before the pandemic. Here’s the picture.

CPI Index for Airfares: 2012 to 2022

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The CPI index for airfares in December was 0.7 percent higher than its level in February of 2020. That is probably not the sort of price increase that will get the Fed or anyone else too worried about inflation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Everyone who carefully follows the news about the economy knows that we are in the middle of the Second Great Depression. On the other hand, those who read less news, but deal with things like jobs, wages, and bills probably think the economy is pretty damn good. We got more evidence on the pretty damn good side with the December jobs report and other economic data released in the last week.

The most important part of the jobs report was the drop in the unemployment rate to 3.5 percent. This equals the lowest rate in more than half a century. While many in the media insist that only elite intellectual types care about jobs, not ordinary workers, since the ability to pay for food, rent, and other bills is tightly linked to having a job, it seems that at least some workers might care about being able to work.

For these people, the tight labor market we have seen as the economy recovered from the pandemic recession is really good news. Not only do people have jobs, but the strong labor market means they can quit bad jobs. If the pay is low, the working conditions are bad, the boss is a jerk, workers can go elsewhere.

And, they are choosing to do so in large numbers. In November, the most recent month for which we have data, 2.7 percent of all workers, 4.2 million people, quit their job. This is near the record high of 3.0 percent reported at the end of 2021, and still above the highs reached before the pandemic and at the end of the 1990s boom.

The ability to quit bad jobs has predictably led to rising wages. Employers must raise pay to attract and retain workers. Real wages were dropping at the end of 2021 and the first half of 2022, as inflation outpaced wage growth, but as inflation slowed in the last half year, real wages have been rising at a healthy pace.

From June to November, the real average hourly wage has increased by 0.9 percent, a 2.2 percent annual rate. (We don’t have December price data yet.) Workers lower down the pay scale have done even better. The real average hourly wage for production and non-supervisory workers, a category that excludes managers and other highly paid workers, has risen by 1.4 percent since June, a 3.3 percent annual rate of increase. In the hotel and restaurant sectors, real pay has risen by 1.8 percent since June, a 4.4 percent annual rate of increase.

These real pay gains follow declines in 2021 and first half of 2022, but for many workers pay is already above the pre-pandemic level. For production and non-supervisory workers, the real average hourly wage is 0.3 percent above the February, 2020 level. For production and non-supervisory workers in the hotel and restaurant sectors real pay is up by 4.7 percent. The overall average for all workers is only down by 0.3 percent, a gap that will likely be largely eliminated by the wage growth reported for December.

While we may still have problems with inflation going forward, the sharp slowing in recent months was an unexpected surprise. We saw gas prices fall most of the way back to pre-pandemic levels. Many of the items where prices rose sharply due to supply chain problems, like appliances and furniture, are now seeing rapid drops in prices. Rents, which are a huge factor in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and people’s budgets, have slowed sharply and are now falling in many areas. It will be several months before this slowing shows up in the CPI because of its methodology for measuring rental inflation, but based on private indexes of marketed housing units, we can be certain we will see rents rising much more slowly soon.

In short, there are good reasons for believing that we will see much slower inflation going forward. If we continue to see moderate nominal wage growth in 2023, that will translate into a healthy pace of real wage growth.

Homeownership

Also, contrary to what is widely reported, we had a largely positive picture on housing in the last three years. While current mortgage rates are pricing many people out of the market, homeownership did rise rapidly since the pandemic

The overall homeownership rate increased by 1.0 percentage point from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2022. For Blacks, it rose by 1.2 percentage points, from 44.0 percent to 45.2 percent. For young people it rose by 1.7 percentage points, from 37.6 percent to 39.3 percent. For lower income households it rose by 1.3 percentage points from 51.4 percent to 52.7 percent.

It is striking that this rise in homeownership, especially for the most disadvantaged groups, is 180 degrees at odds with what is being reported in the media. These data come from the Census Bureau, which is generally considered an authoritative source. Nonetheless, the media have insisted that this has been a period in which young people, minorities, and low-income households have faced extraordinary difficulties in buying houses.

Income Growth

The media have also frequently told us that people are being forced to dip into their savings and that the saving rate is now at a record low. While the saving rate has fallen sharply in the last year, a major factor is that people have sold stock at large gains and are now paying capital gains taxes on these gains. Capital gains do not count as income, but the taxes paid on these gains are deducted from income in the national accounts, thereby lowering the saving rate. It’s not clear that people who sold stock at a gain, and then pay tax on that gain, are suffering severe financial hardship.

We also have the story of rapidly rising credit card debt. This has been presented as another indication of financial hardship. There actually is a simple and very different story. In 2020 and 2021, tens of millions of homeowners took advantage of extraordinarily low mortgage rates to refinance their homes. When they refinanced, they often would borrow more than their original mortgage to pay for various expenses they might be facing.

The Fed’s rate hikes have largely put an end to refinancing, including cash-out refinancing. With this channel closed to households, people that formerly would have looked to borrow by refinancing mortgage are instead turning to credit cards. This is hardly a crisis. Furthermore, tens of millions of families that were paying thousands more in mortgage interest, now have additional money to spend or save. This is not reflected in aggregate data.

It’s also worth noting one reason that inflation may have left many people strapped: the cost-of-living adjustments for Social Security are only paid once a year. This meant the checks beneficiaries were getting could buy around 7.0 percent less in December than they had the start of the year. However, Social Security beneficiaries are seeing an 8.7 percent increase in the size of their checks this month. That should make life considerably easier for tens of millions of retirees, and also modestly boost the saving rate.

Productivity Growth and Working from Home

Other bright spots in the economy include the return of healthy productivity growth and the huge increase in the number of people working from home. We saw two quarters of negative productivity growth in the first half of last year.

Productivity growth is poorly measured and highly erratic, but there seems little doubt that productivity growth was very poor in the first and second quarters of 2022. This added to the inflationary pressure that businesses were seeing.

This situation was reversed in the third quarter, with productivity growth coming in at close to 1.0 percent, roughly in line with the pre-pandemic trend. It looks like productivity growth will be even better in fourth quarter. GDP growth is now projected to be well over 3.0 percent, while payroll hours grew at just a 1.0 percent annual rate, implying a productivity growth rate close to 2.0 percent. This would be great news if it can be sustained, but as always, a single quarter’s data has to be viewed with great caution.

The other big positive in the economic picture is the huge increase in the number of people working from home. One recent paper estimated that 30 percent of all workdays are now remote, up from around 10 percent before the pandemic. While that number may prove somewhat high, it is clear that tens of millions of workers are now saving thousands a year on commuting costs and hundreds of hours formerly spent commuting. That is also a huge deal which is not picked up in our national accounts.

If the Economy Is Great, Why Do People Say They Think It Is Awful?

I’m not going to try to answer that one, other than to note that there has been a “horrible economy” echo chamber in the media, where facts have often been distorted or ignored altogether. I don’t know if that explains why so many people say they think the economy is bad, I’m an economist, not a social psychologist.

I will say that people are not acting like they think the economy is bad. They are buying huge amounts of big-ticket items like appliances and furniture, and until very recently houses. They are also going out to restaurants at a higher rate than before the pandemic. This is not behavior we would expect from people who feel their economic prospects are bleak.

To be clear, there are tens of millions of people who are struggling. Many can’t pay the rent, buy decent food and clothes for their kids, or pay for needed medicine or medical care. That is a horrible story, but this unfortunately is true even in the best of economic times. Until we adopt policies to protect people facing severe hardship we will have tens of millions of people struggling to get the necessities of life.

But this is not the horrible economy story the media is telling us. That is one that is suppose to apply to people higher up the income ladder. And, thankfully that story only exists in the media’s reporting, not in the economic data.

Everyone who carefully follows the news about the economy knows that we are in the middle of the Second Great Depression. On the other hand, those who read less news, but deal with things like jobs, wages, and bills probably think the economy is pretty damn good. We got more evidence on the pretty damn good side with the December jobs report and other economic data released in the last week.

The most important part of the jobs report was the drop in the unemployment rate to 3.5 percent. This equals the lowest rate in more than half a century. While many in the media insist that only elite intellectual types care about jobs, not ordinary workers, since the ability to pay for food, rent, and other bills is tightly linked to having a job, it seems that at least some workers might care about being able to work.

For these people, the tight labor market we have seen as the economy recovered from the pandemic recession is really good news. Not only do people have jobs, but the strong labor market means they can quit bad jobs. If the pay is low, the working conditions are bad, the boss is a jerk, workers can go elsewhere.

And, they are choosing to do so in large numbers. In November, the most recent month for which we have data, 2.7 percent of all workers, 4.2 million people, quit their job. This is near the record high of 3.0 percent reported at the end of 2021, and still above the highs reached before the pandemic and at the end of the 1990s boom.

The ability to quit bad jobs has predictably led to rising wages. Employers must raise pay to attract and retain workers. Real wages were dropping at the end of 2021 and the first half of 2022, as inflation outpaced wage growth, but as inflation slowed in the last half year, real wages have been rising at a healthy pace.

From June to November, the real average hourly wage has increased by 0.9 percent, a 2.2 percent annual rate. (We don’t have December price data yet.) Workers lower down the pay scale have done even better. The real average hourly wage for production and non-supervisory workers, a category that excludes managers and other highly paid workers, has risen by 1.4 percent since June, a 3.3 percent annual rate of increase. In the hotel and restaurant sectors, real pay has risen by 1.8 percent since June, a 4.4 percent annual rate of increase.

These real pay gains follow declines in 2021 and first half of 2022, but for many workers pay is already above the pre-pandemic level. For production and non-supervisory workers, the real average hourly wage is 0.3 percent above the February, 2020 level. For production and non-supervisory workers in the hotel and restaurant sectors real pay is up by 4.7 percent. The overall average for all workers is only down by 0.3 percent, a gap that will likely be largely eliminated by the wage growth reported for December.

While we may still have problems with inflation going forward, the sharp slowing in recent months was an unexpected surprise. We saw gas prices fall most of the way back to pre-pandemic levels. Many of the items where prices rose sharply due to supply chain problems, like appliances and furniture, are now seeing rapid drops in prices. Rents, which are a huge factor in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and people’s budgets, have slowed sharply and are now falling in many areas. It will be several months before this slowing shows up in the CPI because of its methodology for measuring rental inflation, but based on private indexes of marketed housing units, we can be certain we will see rents rising much more slowly soon.

In short, there are good reasons for believing that we will see much slower inflation going forward. If we continue to see moderate nominal wage growth in 2023, that will translate into a healthy pace of real wage growth.

Homeownership

Also, contrary to what is widely reported, we had a largely positive picture on housing in the last three years. While current mortgage rates are pricing many people out of the market, homeownership did rise rapidly since the pandemic

The overall homeownership rate increased by 1.0 percentage point from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the third quarter of 2022. For Blacks, it rose by 1.2 percentage points, from 44.0 percent to 45.2 percent. For young people it rose by 1.7 percentage points, from 37.6 percent to 39.3 percent. For lower income households it rose by 1.3 percentage points from 51.4 percent to 52.7 percent.

It is striking that this rise in homeownership, especially for the most disadvantaged groups, is 180 degrees at odds with what is being reported in the media. These data come from the Census Bureau, which is generally considered an authoritative source. Nonetheless, the media have insisted that this has been a period in which young people, minorities, and low-income households have faced extraordinary difficulties in buying houses.

Income Growth

The media have also frequently told us that people are being forced to dip into their savings and that the saving rate is now at a record low. While the saving rate has fallen sharply in the last year, a major factor is that people have sold stock at large gains and are now paying capital gains taxes on these gains. Capital gains do not count as income, but the taxes paid on these gains are deducted from income in the national accounts, thereby lowering the saving rate. It’s not clear that people who sold stock at a gain, and then pay tax on that gain, are suffering severe financial hardship.

We also have the story of rapidly rising credit card debt. This has been presented as another indication of financial hardship. There actually is a simple and very different story. In 2020 and 2021, tens of millions of homeowners took advantage of extraordinarily low mortgage rates to refinance their homes. When they refinanced, they often would borrow more than their original mortgage to pay for various expenses they might be facing.

The Fed’s rate hikes have largely put an end to refinancing, including cash-out refinancing. With this channel closed to households, people that formerly would have looked to borrow by refinancing mortgage are instead turning to credit cards. This is hardly a crisis. Furthermore, tens of millions of families that were paying thousands more in mortgage interest, now have additional money to spend or save. This is not reflected in aggregate data.

It’s also worth noting one reason that inflation may have left many people strapped: the cost-of-living adjustments for Social Security are only paid once a year. This meant the checks beneficiaries were getting could buy around 7.0 percent less in December than they had the start of the year. However, Social Security beneficiaries are seeing an 8.7 percent increase in the size of their checks this month. That should make life considerably easier for tens of millions of retirees, and also modestly boost the saving rate.

Productivity Growth and Working from Home

Other bright spots in the economy include the return of healthy productivity growth and the huge increase in the number of people working from home. We saw two quarters of negative productivity growth in the first half of last year.

Productivity growth is poorly measured and highly erratic, but there seems little doubt that productivity growth was very poor in the first and second quarters of 2022. This added to the inflationary pressure that businesses were seeing.

This situation was reversed in the third quarter, with productivity growth coming in at close to 1.0 percent, roughly in line with the pre-pandemic trend. It looks like productivity growth will be even better in fourth quarter. GDP growth is now projected to be well over 3.0 percent, while payroll hours grew at just a 1.0 percent annual rate, implying a productivity growth rate close to 2.0 percent. This would be great news if it can be sustained, but as always, a single quarter’s data has to be viewed with great caution.

The other big positive in the economic picture is the huge increase in the number of people working from home. One recent paper estimated that 30 percent of all workdays are now remote, up from around 10 percent before the pandemic. While that number may prove somewhat high, it is clear that tens of millions of workers are now saving thousands a year on commuting costs and hundreds of hours formerly spent commuting. That is also a huge deal which is not picked up in our national accounts.

If the Economy Is Great, Why Do People Say They Think It Is Awful?

I’m not going to try to answer that one, other than to note that there has been a “horrible economy” echo chamber in the media, where facts have often been distorted or ignored altogether. I don’t know if that explains why so many people say they think the economy is bad, I’m an economist, not a social psychologist.

I will say that people are not acting like they think the economy is bad. They are buying huge amounts of big-ticket items like appliances and furniture, and until very recently houses. They are also going out to restaurants at a higher rate than before the pandemic. This is not behavior we would expect from people who feel their economic prospects are bleak.

To be clear, there are tens of millions of people who are struggling. Many can’t pay the rent, buy decent food and clothes for their kids, or pay for needed medicine or medical care. That is a horrible story, but this unfortunately is true even in the best of economic times. Until we adopt policies to protect people facing severe hardship we will have tens of millions of people struggling to get the necessities of life.

But this is not the horrible economy story the media is telling us. That is one that is suppose to apply to people higher up the income ladder. And, thankfully that story only exists in the media’s reporting, not in the economic data.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The New York Times had a major article reporting on how many people in South Korea, Hong Kong, and Japan are being forced to work well into their seventies because they lack sufficient income to retire. The piece presents this as a problem of aging societies, which will soon hit the United States and other rich countries with declining birth rates and limited immigration.

While the plight of the older workers discussed in the article is a real problem, the cause is not the aging of the population. The reason these people don’t have adequate income to retire is a political decision about the distribution of income.

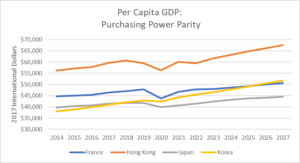

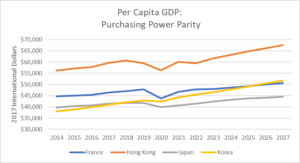

If the issue was simply that too few people were working in these aging societies, we should expect to see slower per capita growth than in countries where aging is less of a problem. That is not the case. The figure below shows real per capita income in these three countries from 2014, along with projections to 2027, as well as France, which has maintained a relatively high birth rate.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

As can be seen, both Korea and Hong Kong have been seeing more rapid per capita GDP growth than France and are projected to continue to do so, with Japan’s growth rate virtually identical over this period. Korea is projected to maintain a 2.4 percent growth rate, while Hong Kong is projected to have a 1.4 percent annual growth rate. By comparison, France is projected to have a 0.94 percent growth rate, only slightly higher than Japan’s 0.9 percent rate.

The conventional story of a country facing problems due to aging would be that it stops seeing per capita income growth, and could even see declines, as the ratio of workers to total population falls. Two of the three countries highlighted are sustaining considerably more rapid per capita growth than a country that is less affected by an aging population. In the third case, the growth is essentially identical.

This means that the reason older people are unable to retire in these countries is not the aging of the population, but the political decision to not provide adequate support for the elderly population. In short, the problem is political, not demographics.

The New York Times had a major article reporting on how many people in South Korea, Hong Kong, and Japan are being forced to work well into their seventies because they lack sufficient income to retire. The piece presents this as a problem of aging societies, which will soon hit the United States and other rich countries with declining birth rates and limited immigration.

While the plight of the older workers discussed in the article is a real problem, the cause is not the aging of the population. The reason these people don’t have adequate income to retire is a political decision about the distribution of income.

If the issue was simply that too few people were working in these aging societies, we should expect to see slower per capita growth than in countries where aging is less of a problem. That is not the case. The figure below shows real per capita income in these three countries from 2014, along with projections to 2027, as well as France, which has maintained a relatively high birth rate.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

As can be seen, both Korea and Hong Kong have been seeing more rapid per capita GDP growth than France and are projected to continue to do so, with Japan’s growth rate virtually identical over this period. Korea is projected to maintain a 2.4 percent growth rate, while Hong Kong is projected to have a 1.4 percent annual growth rate. By comparison, France is projected to have a 0.94 percent growth rate, only slightly higher than Japan’s 0.9 percent rate.

The conventional story of a country facing problems due to aging would be that it stops seeing per capita income growth, and could even see declines, as the ratio of workers to total population falls. Two of the three countries highlighted are sustaining considerably more rapid per capita growth than a country that is less affected by an aging population. In the third case, the growth is essentially identical.

This means that the reason older people are unable to retire in these countries is not the aging of the population, but the political decision to not provide adequate support for the elderly population. In short, the problem is political, not demographics.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• EuropeEuropaUnited KingdomWorldEl Mundo

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• HousingRentUnited StatesEE. UU.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

This is Dean’s colleague Dawn, CEPR’s Development Director, taking over his blog as I have done for the past 15 years to thank you for supporting Dean’s work! Please bear with me, those of you who have read my hijacked posts over the years, because I’m going to make the same spiel as always.

OK, for those of you who don’t know, Dean makes a point of providing all of his work for F-R-E-E. His books are free to download! His Patreon account is set at the minimum pledge of $1.00 per month, and if it were up to Dean it would be $0. (Please consider signing up to be a patron of BTP!)

While I find Dean’s morals and ethics to be beyond reproach, as a fundraiser he makes my job extremely difficult. Unlike other think tanks, CEPR doesn’t offer special access to our researchers for a fee. We don’t take any corporate funding (not that billion-dollar corporations are knocking down our door. Right, Elon?). We truly rely on the generosity of individual donors to help fund our work.

On behalf of Dean and everyone at CEPR, many thanks for supporting us this past year. If you haven’t already, please consider donating to CEPR this holiday season.

OK, back to your regularly scheduled program. And remember, as Dean always says: Don’t believe everything you read in the papers (or online).

This is Dean’s colleague Dawn, CEPR’s Development Director, taking over his blog as I have done for the past 15 years to thank you for supporting Dean’s work! Please bear with me, those of you who have read my hijacked posts over the years, because I’m going to make the same spiel as always.

OK, for those of you who don’t know, Dean makes a point of providing all of his work for F-R-E-E. His books are free to download! His Patreon account is set at the minimum pledge of $1.00 per month, and if it were up to Dean it would be $0. (Please consider signing up to be a patron of BTP!)

While I find Dean’s morals and ethics to be beyond reproach, as a fundraiser he makes my job extremely difficult. Unlike other think tanks, CEPR doesn’t offer special access to our researchers for a fee. We don’t take any corporate funding (not that billion-dollar corporations are knocking down our door. Right, Elon?). We truly rely on the generosity of individual donors to help fund our work.

On behalf of Dean and everyone at CEPR, many thanks for supporting us this past year. If you haven’t already, please consider donating to CEPR this holiday season.

OK, back to your regularly scheduled program. And remember, as Dean always says: Don’t believe everything you read in the papers (or online).

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Health and Social ProgramsLos Programas Sociales y de Salud

Since coming to Washington more than three decades ago, I have spent much of my time working on retirement income. The biggest part of that story was defending Social Security, which leaders in both parties were anxious to cut. This defense was largely successful, as the efforts to privatize it in the 1990s and under President Bush were beaten back, and the efforts at cuts often focused on the annual cost of living adjustment, were similarly derailed.

Defending Social Security was crucial, both because tens of millions of people depend on it for most or all of their income, but also because it was a model social program. The administrative costs are minimal, with the total program’s costs coming to less than 0.6 percent of annual benefits, with the costs of the retirement program alone coming to less than 0.4 percent of benefits. By comparison, the fees from private 401(k)s run in the neighborhood of 15 to 20 percent of annual retirement benefits.

There is also very little fraud in the program. The Washington Post, which has long been one of the leading advocates for cutting Social Security in both its opinion and news sections, once devoted a major investigative piece to exposing the fact that 0.006 percent of benefit payments went to dead people, more than half of which were later recovered. It lately decried Social Security as a “mess” in the headline to a full-page article.

I always felt that it was essential to defend Social Security because it could serve as a model for other programs, like universal Medicare or child care. But, as necessary as Social Security is, I also recognized the need to have some additional retirement income for much of the population.

Supplements to Social Security

The traditional story about retirement income was that it was a three-legged stool. Workers were supposed to have Social Security as their core retirement income. In addition, they should have a workplace pension, and also personal savings. That story could reasonably accurately describe the situation of millions of middle-class workers in the years after World War II to the 1990s, but in recent decades the other two legs of this stool have been largely removed.

Traditionally defined benefit pensions (DB) have been eliminated mainly in the private sector. While current retirees can still often count on income from DB pensions, this will be less true going forward. And, most middle-income and moderate-income households have little by way of traditional savings to help support them in retirement. Also, the story of a middle-class household reaching retirement with a paid off mortgage is far less common today than four decades ago.

All of this pointed to the need for some supplement to Social Security. For the lowest income workers, it is not plausible that they will be able to accumulate substantial savings for retirement. People struggling to pay the rent are not going to have tens of thousands stashed away in retirement accounts. The best solution here is an increase in benefits for low-paid workers.

There have been many proposals for increased benefits for lower income workers over the years, some of which had some bipartisan support. For example, giving surviving spouses 75 percent of the joint benefit (compared to the current 66.7 percent, which is often the case now), would be a substantial benefit boost to many of the elderly, generally women. This change can be structured in a way where the cost would be minimal, while providing more than a 12 percent increase in the income of many people who can really use it. There have been many Republicans who have indicated support for this sort of benefit change, although sometimes paring it with cuts that make it unacceptable.

Anyhow, while increased benefits for lower paid workers can drastically improve their well-being in retirement, substantial increases in benefits for middle income workers would be costly. A Social Security program that, by itself, allowed middle-income workers to sustain their living standards in retirement would have to be close to twice the size of the current program. That does not look very feasible.

For this reason, many of us have sought to create a simple low-cost voluntary retirement program that would supplement Social Security. The idea was to make it easy and cheap for workers to save for retirement.

The strategy takes advantage of one of the clearest findings from behavioral economics. When it comes to voluntary retirement plans, workers will overwhelmingly go with a default option. If they are automatically enrolled in a plan, with the option to disenroll, many more workers will stay with the retirement plan than if they have to make the decision to actively enroll in the plan. This is true even when there is money on the table in the form of a matching contribution from an employer.

For this reason, the idea was to make enrollment the default option. If workers decided that it was more important that they have the money to meet current expenses, they just have to opt out of their retirement plan.

That is the simple part. The cheap part was to have a low-cost plan available to all workers. Many 401(k)s and IRA(s) rip-off their participants. Average fees for 401(k)s are in the range of 1.0 percent a year for the company managing the account, with fees for the funds in the account sometimes adding another 1.0 percentage point.

If that seems trivial, consider that a middle-income person can easily accumulate $70,000 in a retirement account towards the end of their working life-time. Imagine paying $1,400 a year, to someone you don’t know, for essentially doing nothing. Taken over a working lifetime, a middle-income worker can easily be throwing $20,000 in the toilet (i.e. providing income to the financial sector) in excess account fees. This is money that will come directly out of their retirement savings.

For this reason, we felt that it was essential that the retirement accounts be coupled with a low-cost investment option. The dream for many of us pushing on this issue is that workers would be able to buy into the Federal Employees’ Thrift Saving Plan, which has fees in the neighborhood of 0.1 percent on its accounts, including the fees charged for individual funds.

The State-by-State Strategy

With action at the federal level largely blocked, the focus was on getting states with relatively progressive governors and legislatures to take the lead in both requiring employers to offer workers retirement accounts and to give them a low-cost option. The simple route for the latter was to open up the retirement system for the state’s public sector workers to workers for private employers.

This did not mean co-mingling funds; public sector employees’ pensions would not be affected. The plan was simply to take advantage of the expertise available in the public pension funds to allow workers in the private sector the same investment options. The administrative costs of the state plans are in general far lower than for private sector 401(k)s, so this meant substantial savings for workers.

Several states went this route, notably, Illinois led the way in 2018 with its Secure Choice program, with New York and California also implementing comparable programs. As it is, a large share of the nation’s workers now lives in a state where most employers are required to enroll workers in retirement plans managed by the government’s public employee pension system unless they offer their own plan.

Secure 2.0 Makes Default Accounts National

In order to ensure that all workers have a decent living standard in retirement it is necessary to have a national program. The Secure 2.0 Act provisions in the omnibus spending go a very long way in this direction. They will require employers with more than ten workers to put at least 3.0 percent of their pay in a retirement fund each year for their workers. The amount will rise by a percentage point each year, until it hits 10 percent.

This is an optional contribution on the part of the employee, they can choose to have this money in their paycheck, if they would prefer to have the money now. In effect, this is just changing the default option. They will be saving, unless they choose not to, rather than the current situation where they have to make a conscious choice to save for retirement.

Another provision in the bill makes the savers’ credit fully refundable. This is a federal tax credit that matched contributions to retirement accounts by low- and moderate-income workers. The problem was that it was not refundable so most of the people with an income low enough to qualify couldn’t benefit since they didn’t owe any income tax. The Secure 2.0 Act provisions fix this so these workers can get the credit even if they don’t owe any income tax.

The Secure 2.0 Act provisions are a big victory, but they don’t address the cost half of the picture. It would be great if, as part of this bill, every worker had the option to have their money invested through the Federal Thrift Savings Plan. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Workers will have to use private insurance companies and brokerages. This means much of their money will be diverted to the Wall Street types.

That is likely a big factor in how the Secure 2.0 provisions got added to the Omnibus bill. While it is great that workers will have more savings for retirement, this bill can mean big money for the financial industry. If the bill increases retirement assets by $1 trillion after ten years (defined contribution plans already have over $6 trillion in assets), it will mean over $10 billion a year in fees for the industry, if the average cost of an account is 1.0 percent of assets. If it is 1.5 percent, adding in the fees for individual funds, that would come to $15 billion a year in fees.

On the other hand, if everyone had the option to invest in the Federal Thrift Savings Plan, we would likely see much of the $6 trillion in assets currently managed by the industry begin to migrate to the federal plan. After all, not that many people are so enamored of insurance companies that they would be willing to throw away thousands of dollars to keep them happy. In that story, they would have more than $60 billion in annual fees at risk, real money even in Washington.

If neo-liberals actually care about efficiency, as they profess, they would be all over this one. After all, the money saved by having a more efficient retirement system would swamp the money involved in tariffs on steel and other things that get them excited. But no one expects neo-liberals to be consistent.

Allowing people to opt into the Federal Thrift Savings Plan should be an ongoing demand for progressives going forward. The industry will be prepared to kill to prevent this from happening, but they lack a serious argument. After all, we can steal a line from their Social Security privatization efforts, “what’s wrong with giving people a choice?”

The State-by-State Strategy

The passage of the Secure Act 2.0 provisions is also a vindication of the state-by-state strategy that progressives have been pursuing for the last quarter century when action at the national level seems blocked. This has been done with increases to the minimum wage, paid sick days and family leave, support for child care, and a number of other areas.

This strategy is effective in both directly providing benefits to large numbers of people, especially in large states like California and New York, and also making policies seem feasible to much of the country. Many of us have been in the habit of pointing to policies successfully implemented in places like Germany, France, or Denmark, but to much of the country we might just as well be talking about Mars. When we can point to a state that has a $15 minimum wage or paid family leave, it sounds like a plausible option for the country.

In the case of the Secure Act 2.0 provisions, many states had already implemented similar bills without the catastrophic effects that businesses often claim will result from progressive legislation. This could give members of Congress confidence that businesses can easily deal with the requirements in the bill.

It also may be good for many companies since offering a retirement plan may help them retain good workers. It’s true that businesses already have this option, but as behavioral economics teaches us, people may often not do what is best for them.

Anyhow, this is one more vindication of the strategy to pursue policies at the state, or even local level, when the prospects for federal action seem bleak. (Yes, I do talk about this in Rigged [it’s free].) It is nice to see a victory here – a good holiday present for tens of millions of workers who stand to benefit.

Since coming to Washington more than three decades ago, I have spent much of my time working on retirement income. The biggest part of that story was defending Social Security, which leaders in both parties were anxious to cut. This defense was largely successful, as the efforts to privatize it in the 1990s and under President Bush were beaten back, and the efforts at cuts often focused on the annual cost of living adjustment, were similarly derailed.

Defending Social Security was crucial, both because tens of millions of people depend on it for most or all of their income, but also because it was a model social program. The administrative costs are minimal, with the total program’s costs coming to less than 0.6 percent of annual benefits, with the costs of the retirement program alone coming to less than 0.4 percent of benefits. By comparison, the fees from private 401(k)s run in the neighborhood of 15 to 20 percent of annual retirement benefits.

There is also very little fraud in the program. The Washington Post, which has long been one of the leading advocates for cutting Social Security in both its opinion and news sections, once devoted a major investigative piece to exposing the fact that 0.006 percent of benefit payments went to dead people, more than half of which were later recovered. It lately decried Social Security as a “mess” in the headline to a full-page article.

I always felt that it was essential to defend Social Security because it could serve as a model for other programs, like universal Medicare or child care. But, as necessary as Social Security is, I also recognized the need to have some additional retirement income for much of the population.

Supplements to Social Security

The traditional story about retirement income was that it was a three-legged stool. Workers were supposed to have Social Security as their core retirement income. In addition, they should have a workplace pension, and also personal savings. That story could reasonably accurately describe the situation of millions of middle-class workers in the years after World War II to the 1990s, but in recent decades the other two legs of this stool have been largely removed.

Traditionally defined benefit pensions (DB) have been eliminated mainly in the private sector. While current retirees can still often count on income from DB pensions, this will be less true going forward. And, most middle-income and moderate-income households have little by way of traditional savings to help support them in retirement. Also, the story of a middle-class household reaching retirement with a paid off mortgage is far less common today than four decades ago.

All of this pointed to the need for some supplement to Social Security. For the lowest income workers, it is not plausible that they will be able to accumulate substantial savings for retirement. People struggling to pay the rent are not going to have tens of thousands stashed away in retirement accounts. The best solution here is an increase in benefits for low-paid workers.

There have been many proposals for increased benefits for lower income workers over the years, some of which had some bipartisan support. For example, giving surviving spouses 75 percent of the joint benefit (compared to the current 66.7 percent, which is often the case now), would be a substantial benefit boost to many of the elderly, generally women. This change can be structured in a way where the cost would be minimal, while providing more than a 12 percent increase in the income of many people who can really use it. There have been many Republicans who have indicated support for this sort of benefit change, although sometimes paring it with cuts that make it unacceptable.

Anyhow, while increased benefits for lower paid workers can drastically improve their well-being in retirement, substantial increases in benefits for middle income workers would be costly. A Social Security program that, by itself, allowed middle-income workers to sustain their living standards in retirement would have to be close to twice the size of the current program. That does not look very feasible.

For this reason, many of us have sought to create a simple low-cost voluntary retirement program that would supplement Social Security. The idea was to make it easy and cheap for workers to save for retirement.

The strategy takes advantage of one of the clearest findings from behavioral economics. When it comes to voluntary retirement plans, workers will overwhelmingly go with a default option. If they are automatically enrolled in a plan, with the option to disenroll, many more workers will stay with the retirement plan than if they have to make the decision to actively enroll in the plan. This is true even when there is money on the table in the form of a matching contribution from an employer.

For this reason, the idea was to make enrollment the default option. If workers decided that it was more important that they have the money to meet current expenses, they just have to opt out of their retirement plan.

That is the simple part. The cheap part was to have a low-cost plan available to all workers. Many 401(k)s and IRA(s) rip-off their participants. Average fees for 401(k)s are in the range of 1.0 percent a year for the company managing the account, with fees for the funds in the account sometimes adding another 1.0 percentage point.

If that seems trivial, consider that a middle-income person can easily accumulate $70,000 in a retirement account towards the end of their working life-time. Imagine paying $1,400 a year, to someone you don’t know, for essentially doing nothing. Taken over a working lifetime, a middle-income worker can easily be throwing $20,000 in the toilet (i.e. providing income to the financial sector) in excess account fees. This is money that will come directly out of their retirement savings.

For this reason, we felt that it was essential that the retirement accounts be coupled with a low-cost investment option. The dream for many of us pushing on this issue is that workers would be able to buy into the Federal Employees’ Thrift Saving Plan, which has fees in the neighborhood of 0.1 percent on its accounts, including the fees charged for individual funds.

The State-by-State Strategy

With action at the federal level largely blocked, the focus was on getting states with relatively progressive governors and legislatures to take the lead in both requiring employers to offer workers retirement accounts and to give them a low-cost option. The simple route for the latter was to open up the retirement system for the state’s public sector workers to workers for private employers.

This did not mean co-mingling funds; public sector employees’ pensions would not be affected. The plan was simply to take advantage of the expertise available in the public pension funds to allow workers in the private sector the same investment options. The administrative costs of the state plans are in general far lower than for private sector 401(k)s, so this meant substantial savings for workers.

Several states went this route, notably, Illinois led the way in 2018 with its Secure Choice program, with New York and California also implementing comparable programs. As it is, a large share of the nation’s workers now lives in a state where most employers are required to enroll workers in retirement plans managed by the government’s public employee pension system unless they offer their own plan.

Secure 2.0 Makes Default Accounts National

In order to ensure that all workers have a decent living standard in retirement it is necessary to have a national program. The Secure 2.0 Act provisions in the omnibus spending go a very long way in this direction. They will require employers with more than ten workers to put at least 3.0 percent of their pay in a retirement fund each year for their workers. The amount will rise by a percentage point each year, until it hits 10 percent.

This is an optional contribution on the part of the employee, they can choose to have this money in their paycheck, if they would prefer to have the money now. In effect, this is just changing the default option. They will be saving, unless they choose not to, rather than the current situation where they have to make a conscious choice to save for retirement.

Another provision in the bill makes the savers’ credit fully refundable. This is a federal tax credit that matched contributions to retirement accounts by low- and moderate-income workers. The problem was that it was not refundable so most of the people with an income low enough to qualify couldn’t benefit since they didn’t owe any income tax. The Secure 2.0 Act provisions fix this so these workers can get the credit even if they don’t owe any income tax.

The Secure 2.0 Act provisions are a big victory, but they don’t address the cost half of the picture. It would be great if, as part of this bill, every worker had the option to have their money invested through the Federal Thrift Savings Plan. Unfortunately, this is not the case. Workers will have to use private insurance companies and brokerages. This means much of their money will be diverted to the Wall Street types.

That is likely a big factor in how the Secure 2.0 provisions got added to the Omnibus bill. While it is great that workers will have more savings for retirement, this bill can mean big money for the financial industry. If the bill increases retirement assets by $1 trillion after ten years (defined contribution plans already have over $6 trillion in assets), it will mean over $10 billion a year in fees for the industry, if the average cost of an account is 1.0 percent of assets. If it is 1.5 percent, adding in the fees for individual funds, that would come to $15 billion a year in fees.

On the other hand, if everyone had the option to invest in the Federal Thrift Savings Plan, we would likely see much of the $6 trillion in assets currently managed by the industry begin to migrate to the federal plan. After all, not that many people are so enamored of insurance companies that they would be willing to throw away thousands of dollars to keep them happy. In that story, they would have more than $60 billion in annual fees at risk, real money even in Washington.

If neo-liberals actually care about efficiency, as they profess, they would be all over this one. After all, the money saved by having a more efficient retirement system would swamp the money involved in tariffs on steel and other things that get them excited. But no one expects neo-liberals to be consistent.

Allowing people to opt into the Federal Thrift Savings Plan should be an ongoing demand for progressives going forward. The industry will be prepared to kill to prevent this from happening, but they lack a serious argument. After all, we can steal a line from their Social Security privatization efforts, “what’s wrong with giving people a choice?”

The State-by-State Strategy

The passage of the Secure Act 2.0 provisions is also a vindication of the state-by-state strategy that progressives have been pursuing for the last quarter century when action at the national level seems blocked. This has been done with increases to the minimum wage, paid sick days and family leave, support for child care, and a number of other areas.

This strategy is effective in both directly providing benefits to large numbers of people, especially in large states like California and New York, and also making policies seem feasible to much of the country. Many of us have been in the habit of pointing to policies successfully implemented in places like Germany, France, or Denmark, but to much of the country we might just as well be talking about Mars. When we can point to a state that has a $15 minimum wage or paid family leave, it sounds like a plausible option for the country.

In the case of the Secure Act 2.0 provisions, many states had already implemented similar bills without the catastrophic effects that businesses often claim will result from progressive legislation. This could give members of Congress confidence that businesses can easily deal with the requirements in the bill.

It also may be good for many companies since offering a retirement plan may help them retain good workers. It’s true that businesses already have this option, but as behavioral economics teaches us, people may often not do what is best for them.

Anyhow, this is one more vindication of the strategy to pursue policies at the state, or even local level, when the prospects for federal action seem bleak. (Yes, I do talk about this in Rigged [it’s free].) It is nice to see a victory here – a good holiday present for tens of millions of workers who stand to benefit.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

One not so good item in the package of retirement fund provisions in the omnibus funding bill raises the age for mandatory distributions from retirement accounts from 72 to 75. This is phased in over a decade, but it does go up immediately to 73 in 2023. It had already been raised from 70.5 years to 72 years in 2019.

The mandatory distribution requirement is based on life expectancy at your current age. This means, for example, if your life expectancy at 72 is ten years, then you have to withdraw (and pay taxes) on roughly 10 percent of the money in your IRA or 401(k). The actual calculations are somewhat more complicated, but this is the basic story.

Anyhow, the ostensible justification for raising the age for mandatory withdrawals was that people are worried about outliving their retirement funds. It is important to realize that this is not really the issue with mandatory withdrawals.

The mandate doesn’t require that people spend the money from their accounts, it just requires they pay taxes on them. This means, for example, if someone had $70,000 in their retirement account (roughly the median for account holders in their sixties, which is a bit more than half the population), and their required distribution was 10 percent, they would have to pull $7,000 out of their account.

They could put this $7,000 into another investment account, they would just have to pay taxes on this money as though it were normal income. The vast majority of retirees would be paying a tax rate of 10 or 12 percent, which means they would owe $700 to $840 in taxes. The rest of the money could be invested for their later years.

Since they would have to pay taxes on their money when they pulled it out in any case, the only loss is the potential investment income from their tax payments. That is not likely to be a major factor in determining whether they will outlive their retirement savings.

There are of course people in higher tax brackets, especially among those in a position to defer withdrawals from their retirement accounts. For someone in the top 37 percent tax bracket, deferring withdrawals can mean large savings. But it is unlikely that these people are actually worried about outliving their retirement accounts.

For these higher income people, this provision is simply one more way to reduce their tax obligations, as were provisions in the bill that raised caps on contributions. Since very few people were contributing at the current caps, raising the caps is simply a way for high income people to shelter more of their income from taxation.

These giveaways to high income people may have been a price worth paying for the other changes in retirement provisions, such as making the savers credit fully refundable so that low income people can benefit, and also requiring most employers to contribute to their workers’ retirement. However, we should be clear that these provisions are designed so that they will only benefit a small group of people at the top of the income distribution. They are not about making it less likely that middle income people will outlive their retirement savings.

One not so good item in the package of retirement fund provisions in the omnibus funding bill raises the age for mandatory distributions from retirement accounts from 72 to 75. This is phased in over a decade, but it does go up immediately to 73 in 2023. It had already been raised from 70.5 years to 72 years in 2019.

The mandatory distribution requirement is based on life expectancy at your current age. This means, for example, if your life expectancy at 72 is ten years, then you have to withdraw (and pay taxes) on roughly 10 percent of the money in your IRA or 401(k). The actual calculations are somewhat more complicated, but this is the basic story.

Anyhow, the ostensible justification for raising the age for mandatory withdrawals was that people are worried about outliving their retirement funds. It is important to realize that this is not really the issue with mandatory withdrawals.

The mandate doesn’t require that people spend the money from their accounts, it just requires they pay taxes on them. This means, for example, if someone had $70,000 in their retirement account (roughly the median for account holders in their sixties, which is a bit more than half the population), and their required distribution was 10 percent, they would have to pull $7,000 out of their account.

They could put this $7,000 into another investment account, they would just have to pay taxes on this money as though it were normal income. The vast majority of retirees would be paying a tax rate of 10 or 12 percent, which means they would owe $700 to $840 in taxes. The rest of the money could be invested for their later years.

Since they would have to pay taxes on their money when they pulled it out in any case, the only loss is the potential investment income from their tax payments. That is not likely to be a major factor in determining whether they will outlive their retirement savings.

There are of course people in higher tax brackets, especially among those in a position to defer withdrawals from their retirement accounts. For someone in the top 37 percent tax bracket, deferring withdrawals can mean large savings. But it is unlikely that these people are actually worried about outliving their retirement accounts.

For these higher income people, this provision is simply one more way to reduce their tax obligations, as were provisions in the bill that raised caps on contributions. Since very few people were contributing at the current caps, raising the caps is simply a way for high income people to shelter more of their income from taxation.

These giveaways to high income people may have been a price worth paying for the other changes in retirement provisions, such as making the savers credit fully refundable so that low income people can benefit, and also requiring most employers to contribute to their workers’ retirement. However, we should be clear that these provisions are designed so that they will only benefit a small group of people at the top of the income distribution. They are not about making it less likely that middle income people will outlive their retirement savings.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Globalization and TradeGlobalización y comercioInequalityLa DesigualdadIntellectual PropertyPropiedad IntelectualUnited StatesEE. UU.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Economic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperación

I have been seeing various posts on Twitter from Republican politicians saying how Joe Biden’s inflation is devastating families as we approach the holidays. Of course, it would be amazing if we didn’t have some discomfort given a worldwide pandemic and a major war in Europe, but we can’t expect that Republican politicians would know about such things.

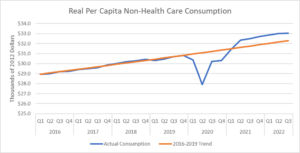

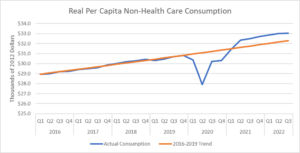

In any case, it is worth seeing the extent to which the data support the Republicans’ tale of hardship. It doesn’t look like the consumption data from the National Income and Product Accounts agree with them. Here’s the picture for real per capita non-health care consumption through the third quarter of 2022.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

As can be seen, non-health care consumption, after falling during the worst period of the pandemic, jumped up in 2021, putting it well above its pre-pandemic trend. In the third quarter of this year, real per capita non-health care consumption was 2.3 percent above its pre-pandemic trend. That doesn’t look like a story of hardship.

We do have to ask about distribution, but it doesn’t seem this is simply a story of the Elon Musks of the world living even higher on the hog. As Arin Dube and David Autor have documented, wage growth since the pandemic has been most rapid for those at the bottom end of the wage distribution, and has outpaced inflation for roughly the bottom 40 percent of the distribution.

It is worth commenting on my use of non-health care consumption. Health care is tricky as a category of consumption. What we care about is health, not the number of doctors visits or medical tests we receive.

Spending on health care has slowed sharply since the pandemic. It is not clear why this is the case. If people are substituting telemedicine and home diagnostics for in-person visits and laboratory tests, this could lead to substantial savings. Whether or not it means worse outcomes remains to be seen.

In any case, it is unambiguously the case that people are consuming more non-health care items this holiday season than they would have reason to expect before the pandemic. The Republicans’ grinch routine is just play acting.

I have been seeing various posts on Twitter from Republican politicians saying how Joe Biden’s inflation is devastating families as we approach the holidays. Of course, it would be amazing if we didn’t have some discomfort given a worldwide pandemic and a major war in Europe, but we can’t expect that Republican politicians would know about such things.

In any case, it is worth seeing the extent to which the data support the Republicans’ tale of hardship. It doesn’t look like the consumption data from the National Income and Product Accounts agree with them. Here’s the picture for real per capita non-health care consumption through the third quarter of 2022.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and author’s calculations.

As can be seen, non-health care consumption, after falling during the worst period of the pandemic, jumped up in 2021, putting it well above its pre-pandemic trend. In the third quarter of this year, real per capita non-health care consumption was 2.3 percent above its pre-pandemic trend. That doesn’t look like a story of hardship.

We do have to ask about distribution, but it doesn’t seem this is simply a story of the Elon Musks of the world living even higher on the hog. As Arin Dube and David Autor have documented, wage growth since the pandemic has been most rapid for those at the bottom end of the wage distribution, and has outpaced inflation for roughly the bottom 40 percent of the distribution.

It is worth commenting on my use of non-health care consumption. Health care is tricky as a category of consumption. What we care about is health, not the number of doctors visits or medical tests we receive.

Spending on health care has slowed sharply since the pandemic. It is not clear why this is the case. If people are substituting telemedicine and home diagnostics for in-person visits and laboratory tests, this could lead to substantial savings. Whether or not it means worse outcomes remains to be seen.

In any case, it is unambiguously the case that people are consuming more non-health care items this holiday season than they would have reason to expect before the pandemic. The Republicans’ grinch routine is just play acting.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión