For folks like Timothy Geithner it is a big thing to boast about the profit the government made on the TARP. We got more of this children’s story in the NYT yesterday in an article reporting on the end of the TARP. It is worth understanding the meaning of profit in this context.

The basic story is fairly simple. The TARP was a program through which we lent otherwise bankrupt banks, and actually bankrupt auto companies, hundreds of billions of dollars at interest rates that were far below the market rate. However the interest was higher than what the government paid on its borrowing, therefore Timothy Geithner gets to run around saying that we made a profit.

Before you start thinking that this is a great idea and we should give all the government’s money to the Wall Street banks, imagine that we had given the same money to an different institution, Bernie Madoff’s investment fund. As we all know, Madoff’s fund was bankrupt at the time because he was running it as a Ponzi, the new investors paid off the earlier investors. He hadn’t made a penny on actual investment in years.

But, if the government had lent him tens of billions of dollars at the rates charged to the Wall Street banks, and furthermore given the Timothy Geithner “no more Lehmans” guarantee (this meant that the government would not allow another major bank to fail), then Madoff would be able to invest the money borrowed from the government in the stock market. In fact, with the no more Lehman’s guarantee he could have borrowed tens or hundreds of billions more from other sources and invested this in the stock market as well. (If he had been a favored bank, he could have also taken advantage of below market interest rate loans from the Fed.)

After a few years, Madoff would have made enough money to cover his shortfall. He could then both repay his investors and repay the loans to the government. This would have then allowed Timothy Geithner to boast about how we made a profit on the loans to Bernie Madoff.

The reality is that the boast of a profit in this context is pretty damn silly. The question is whether an important public purpose was served by rescuing the Wall Street banks from their own greed.

That’s a hard one to see. Geithner and Co. trot out the Second Great Depression scare story, but this is just another children’s story. We have known how to get out of a depression since Keynes, it’s called spending money. And even Republicans are down with stimulus in a severe downturn. The first stimulus was signed by George W. Bush when the unemployment rate was 4.7 percent.

So TARP was about using the government to save the Wall Street banks from the market, end of story. There is no reason for anyone to care that Timothy Geithner gets to say we made a profit on the deal. We could have made a profit on rescuing Bernie Madoff too.

For folks like Timothy Geithner it is a big thing to boast about the profit the government made on the TARP. We got more of this children’s story in the NYT yesterday in an article reporting on the end of the TARP. It is worth understanding the meaning of profit in this context.

The basic story is fairly simple. The TARP was a program through which we lent otherwise bankrupt banks, and actually bankrupt auto companies, hundreds of billions of dollars at interest rates that were far below the market rate. However the interest was higher than what the government paid on its borrowing, therefore Timothy Geithner gets to run around saying that we made a profit.

Before you start thinking that this is a great idea and we should give all the government’s money to the Wall Street banks, imagine that we had given the same money to an different institution, Bernie Madoff’s investment fund. As we all know, Madoff’s fund was bankrupt at the time because he was running it as a Ponzi, the new investors paid off the earlier investors. He hadn’t made a penny on actual investment in years.

But, if the government had lent him tens of billions of dollars at the rates charged to the Wall Street banks, and furthermore given the Timothy Geithner “no more Lehmans” guarantee (this meant that the government would not allow another major bank to fail), then Madoff would be able to invest the money borrowed from the government in the stock market. In fact, with the no more Lehman’s guarantee he could have borrowed tens or hundreds of billions more from other sources and invested this in the stock market as well. (If he had been a favored bank, he could have also taken advantage of below market interest rate loans from the Fed.)

After a few years, Madoff would have made enough money to cover his shortfall. He could then both repay his investors and repay the loans to the government. This would have then allowed Timothy Geithner to boast about how we made a profit on the loans to Bernie Madoff.

The reality is that the boast of a profit in this context is pretty damn silly. The question is whether an important public purpose was served by rescuing the Wall Street banks from their own greed.

That’s a hard one to see. Geithner and Co. trot out the Second Great Depression scare story, but this is just another children’s story. We have known how to get out of a depression since Keynes, it’s called spending money. And even Republicans are down with stimulus in a severe downturn. The first stimulus was signed by George W. Bush when the unemployment rate was 4.7 percent.

So TARP was about using the government to save the Wall Street banks from the market, end of story. There is no reason for anyone to care that Timothy Geithner gets to say we made a profit on the deal. We could have made a profit on rescuing Bernie Madoff too.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Last week I had a blogpost commenting on a snide article in Slate that ridiculed the possibility that people could have chronic Lyme disease for which long-term antibiotic treatment could be useful. (Here‘s a similar piece in Slate.) As I pointed out in that post, the science on chronic Lyme is far less settled than our snide columnist claimed.

Since then I was sent a study that found clear evidence that long-term antibiotic treatment is effective in alleviating the symptoms of chronic Lyme. But apparently the true disbelievers will not allow their views on chronic Lyme to be swayed by new evidence.

Anyhow, the larger context for this discussion is that efforts in trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership and Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Pact to take away regulatory authority from democratically elected officials and turn them over to scientists should be viewed with caution. Unfortunately our scientists often act in ways that show very little respect for science. (Yes, this is probably more true in economics than anywhere.)

Note:

To the folks warning about making claims based on a single study, please go back to my prior post. That post referred to a study that reviewed all the widely cited studies that purportedly show that long-term antibiotic treatment is ineffective. The study noted here is an additional piece of information brought to my attention since that post.

Last week I had a blogpost commenting on a snide article in Slate that ridiculed the possibility that people could have chronic Lyme disease for which long-term antibiotic treatment could be useful. (Here‘s a similar piece in Slate.) As I pointed out in that post, the science on chronic Lyme is far less settled than our snide columnist claimed.

Since then I was sent a study that found clear evidence that long-term antibiotic treatment is effective in alleviating the symptoms of chronic Lyme. But apparently the true disbelievers will not allow their views on chronic Lyme to be swayed by new evidence.

Anyhow, the larger context for this discussion is that efforts in trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership and Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Pact to take away regulatory authority from democratically elected officials and turn them over to scientists should be viewed with caution. Unfortunately our scientists often act in ways that show very little respect for science. (Yes, this is probably more true in economics than anywhere.)

Note:

To the folks warning about making claims based on a single study, please go back to my prior post. That post referred to a study that reviewed all the widely cited studies that purportedly show that long-term antibiotic treatment is ineffective. The study noted here is an additional piece of information brought to my attention since that post.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a discussion of the debate among Democrats on whether they should take credit for the state of the economy. The piece is somewhat confused. It it includes many variables that either have no impact on most people or are not even measures of economic success.

For example, it refers to the decline in the deficit to less than 3.0 percent of GDP. Since the economy is still far below full employment according to estimates of the Congressional Budget Office and other forecasters, this just means that the government is pulling demand out of the economy. It is not clear why this would be a useful accomplishment for the Democrats to boast about.

It also tells readers that “exports are up.” This is especially bizarre, since exports are almost always up and exports are not a measure of economic success. If GM moves an assembly plant from Ohio to Mexico, so that car parts are exported to be assembled in Mexico, exports would be up. Of course the country would have lost the jobs in the Ohio assembly plant and imports would be up even more, leading to a fall in GDP which depends on net exports. Needless to say, the Democrats would look pretty foolish boasting about this.

Remarkably, this piece ignores the importance of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as an economic benefit to the middle class. Every month more than 4.7 million people leave or lose their job. The vast majority of these people are middle class. Over the course of the year this would imply more than 50 million job changers if there were no repeat changers. (There are.) These people no longer have to worry about getting health care insurance for themselves and their families as a result of the ACA. This provides an enormous amount of economic security to the middle class. It is incredible the piece would not discuss this fact. Access to health insurance certainly matters much more to middle class families than the amount of goods the country exports.

The NYT had a discussion of the debate among Democrats on whether they should take credit for the state of the economy. The piece is somewhat confused. It it includes many variables that either have no impact on most people or are not even measures of economic success.

For example, it refers to the decline in the deficit to less than 3.0 percent of GDP. Since the economy is still far below full employment according to estimates of the Congressional Budget Office and other forecasters, this just means that the government is pulling demand out of the economy. It is not clear why this would be a useful accomplishment for the Democrats to boast about.

It also tells readers that “exports are up.” This is especially bizarre, since exports are almost always up and exports are not a measure of economic success. If GM moves an assembly plant from Ohio to Mexico, so that car parts are exported to be assembled in Mexico, exports would be up. Of course the country would have lost the jobs in the Ohio assembly plant and imports would be up even more, leading to a fall in GDP which depends on net exports. Needless to say, the Democrats would look pretty foolish boasting about this.

Remarkably, this piece ignores the importance of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) as an economic benefit to the middle class. Every month more than 4.7 million people leave or lose their job. The vast majority of these people are middle class. Over the course of the year this would imply more than 50 million job changers if there were no repeat changers. (There are.) These people no longer have to worry about getting health care insurance for themselves and their families as a result of the ACA. This provides an enormous amount of economic security to the middle class. It is incredible the piece would not discuss this fact. Access to health insurance certainly matters much more to middle class families than the amount of goods the country exports.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT was seriously misled by the jump in the average hourly wage reported last month, headlining an article, “Economic Recovery Spreads to the Middle Class.” The basis for the headline is the 0.4 percent increase in the average hourly wage reported in November. As fans of wage data everywhere know, the monthly data are very erratic. In fact, the November increase followed two months of weak wage growth. As a result, the annual rate of increase in wages for the most recent three months (September, October, November) compared to the prior three months was just 1.8 percent. That is below the 2.1 percent rate over the last year.

It may turn out that November really is a turning point and we see more rapid wage growth going forward, but given the weakness of the labor market (we are still down 7 million jobs from trend) it is more likely that it was simply a reversal from the unusually low numbers reported the prior two months. It is also worth noting that, contrary to the concern expressed in this article, wages for production and non-supervisory workers have actually been rising somewhat faster than wages for all workers, meaning that less highly paid workers have been seeing relatively larger pay increases in the recovery.

The NYT was seriously misled by the jump in the average hourly wage reported last month, headlining an article, “Economic Recovery Spreads to the Middle Class.” The basis for the headline is the 0.4 percent increase in the average hourly wage reported in November. As fans of wage data everywhere know, the monthly data are very erratic. In fact, the November increase followed two months of weak wage growth. As a result, the annual rate of increase in wages for the most recent three months (September, October, November) compared to the prior three months was just 1.8 percent. That is below the 2.1 percent rate over the last year.

It may turn out that November really is a turning point and we see more rapid wage growth going forward, but given the weakness of the labor market (we are still down 7 million jobs from trend) it is more likely that it was simply a reversal from the unusually low numbers reported the prior two months. It is also worth noting that, contrary to the concern expressed in this article, wages for production and non-supervisory workers have actually been rising somewhat faster than wages for all workers, meaning that less highly paid workers have been seeing relatively larger pay increases in the recovery.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

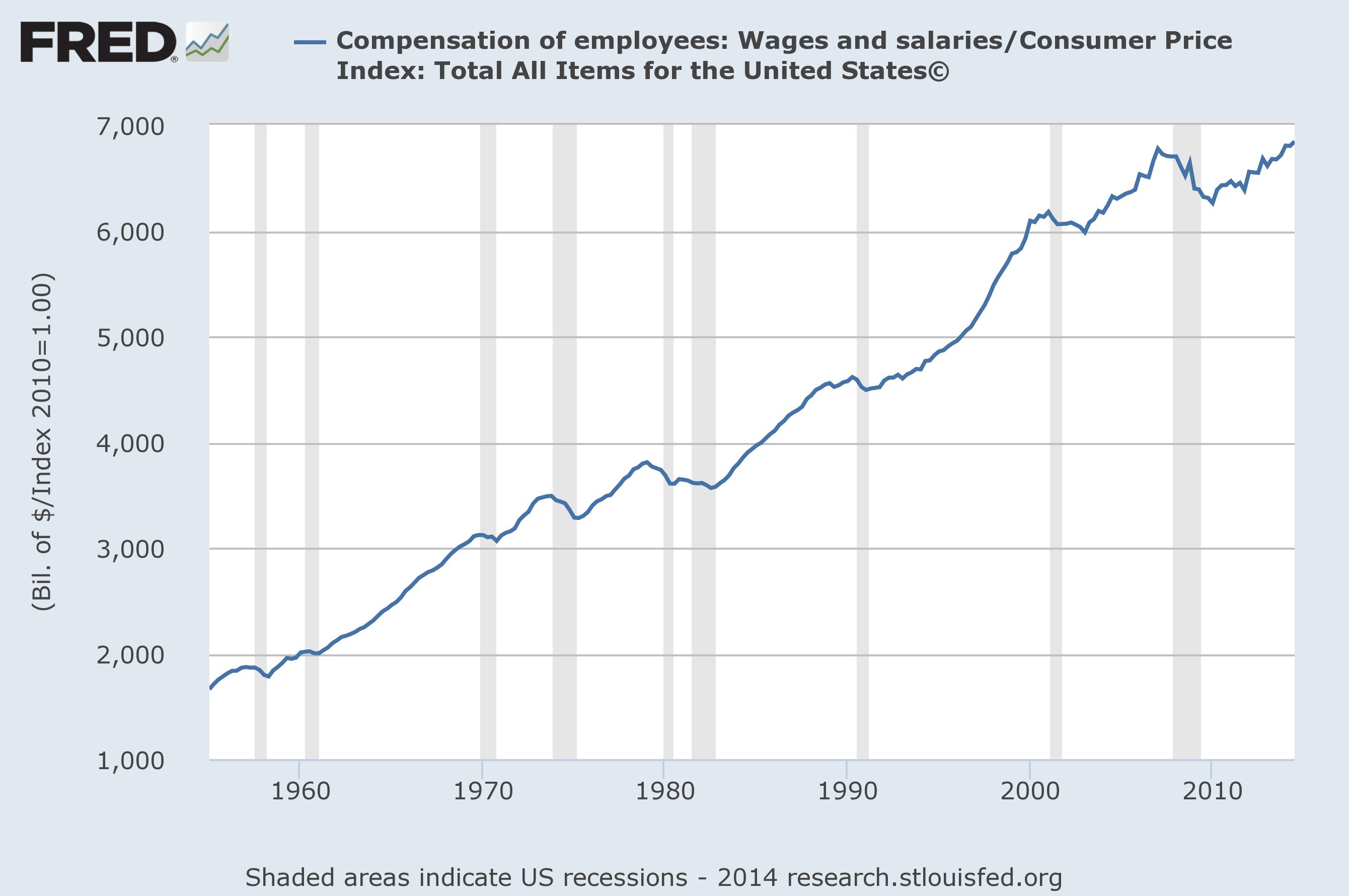

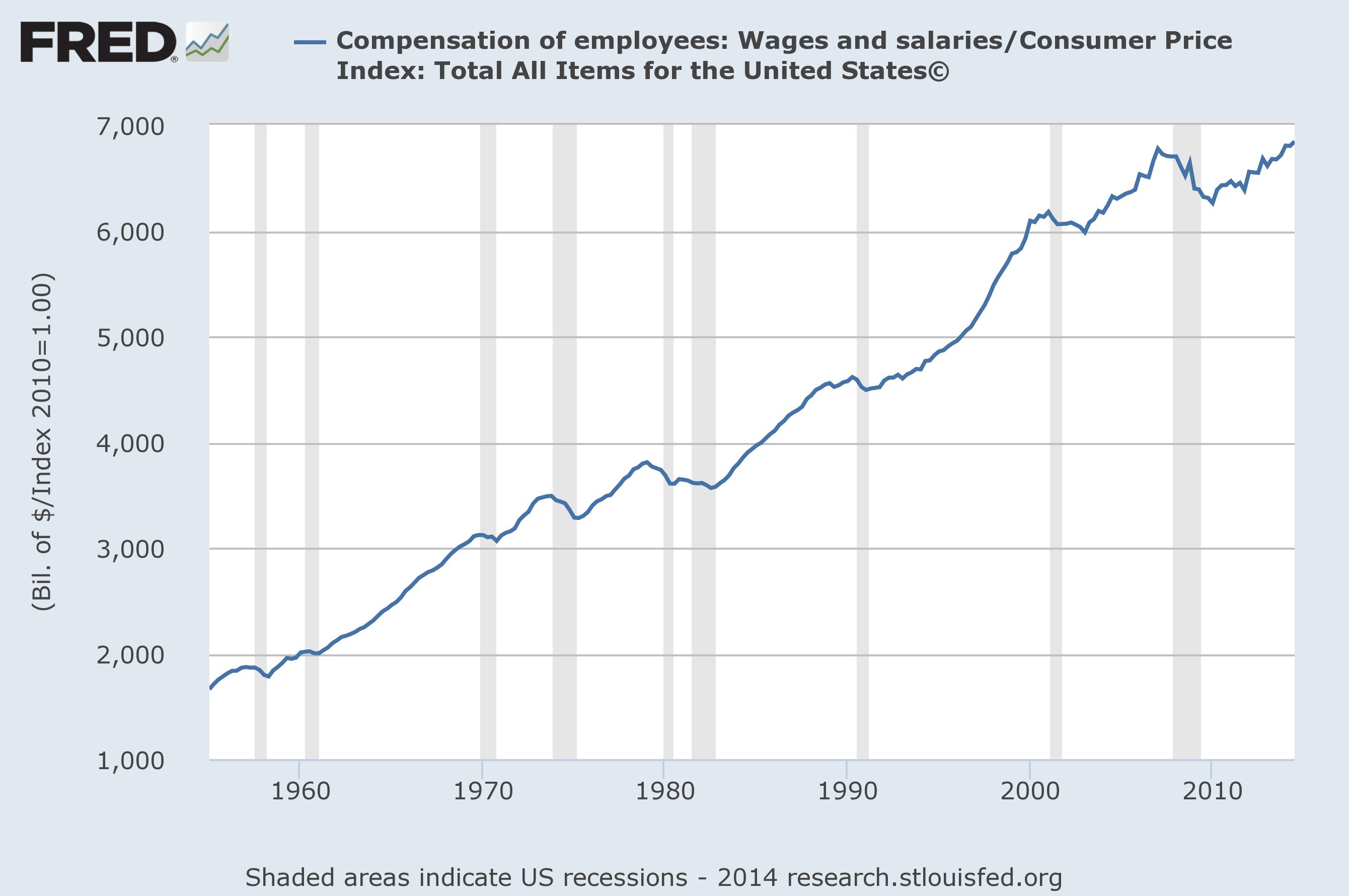

Economies typically grow and that means aggregate wage income typically grows. That is why it is a bit bizarre that in laying out the case for a Fed rate hike, Steve Mufson told readers:

“Inflation-adjusted wages and salaries in personal income rose to a record high during October, up 2.9 percent from the year before.”

That’s pretty much the normal state of affairs, as can be seen.

The Great Recession was extraordinary in giving us a prolonged period in which inflation-adjusted wages did not grow. The fact that we have finally passed the 2007 level is not much of a case for raising interest rates, which just to be clear, means slowing growth and killing jobs.

On this last point the piece includes a mistaken comment from Gregory Mankiw. He is quoted as saying that the percentage of workers who are willing to quit their jobs without having another job lined up is “looking much closer to normal levels.” This is not true. The percentage of unemployment due to people who had voluntarily quit their jobs was 9.1 percent in November. This is above the recession low of 5.5 percent, but it is well below the 11-12 percent range of 2006-2007 and far below the 13-14 percent levels of the late 1990s and 2000, the last time workers saw real wage growth.

Economies typically grow and that means aggregate wage income typically grows. That is why it is a bit bizarre that in laying out the case for a Fed rate hike, Steve Mufson told readers:

“Inflation-adjusted wages and salaries in personal income rose to a record high during October, up 2.9 percent from the year before.”

That’s pretty much the normal state of affairs, as can be seen.

The Great Recession was extraordinary in giving us a prolonged period in which inflation-adjusted wages did not grow. The fact that we have finally passed the 2007 level is not much of a case for raising interest rates, which just to be clear, means slowing growth and killing jobs.

On this last point the piece includes a mistaken comment from Gregory Mankiw. He is quoted as saying that the percentage of workers who are willing to quit their jobs without having another job lined up is “looking much closer to normal levels.” This is not true. The percentage of unemployment due to people who had voluntarily quit their jobs was 9.1 percent in November. This is above the recession low of 5.5 percent, but it is well below the 11-12 percent range of 2006-2007 and far below the 13-14 percent levels of the late 1990s and 2000, the last time workers saw real wage growth.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT’s Upshot section ran a major piece headlined “as robots grow smarter, American workers struggle to keep up.” The gist of the piece is that robots are rapidly replacing workers, leading to a lack of jobs. The piece focuses on the drop in employment in the last decade, which it attributes to the spread of robotization and computer technology. It includes comments from several economists pontificating about the impact on the distribution of income.

If robots and computers are leading to the rapid displacement of workers, they are managing to keep it a secret from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). BLS actually measures the rate at which the economy is becoming more efficient through the use of things like robots and computers, it’s called “productivity growth.”

Fans of data know that, contrary to what you read in the NYT, productivity growth has actually been rather slow in recent years. In the last decade it has averaged less than 1.5 percent annually. By comparison, in the twenty six years from 1947 to 1973 productivity growth averaged 2.8 percent annually. Contrary to the concerns expressed in this article, the rapid spread of technology in that period was associated with low rates of unemployment and high rates of wage growth for the bulk of the population.

The more obvious reason for the drop in employment over the last decade is the loss of demand that resulted from the collapse of the housing bubble. (Did they miss this one at the NYT?) That happens to fit the data like a glove, unlike the speculation on productivity.

Also,if we are discussing demand and employment it is probably worth mentioning the trade deficit. This translates into more than $500 billion in lost annual demand (@ 3.0 percent of GDP). The trade deficit implies demand being created in Europe or Japan, not the United States.

What the hell is the problem with papers not being able to talk about the trade deficit, is there censorship on the topic? This is basic national income accounting. This means it is not an arguable point, those who don’t recognize the trade deficit as a drain on demand in the context of an economy that is below full employment (as discussed here) are simply wrong. The NYT should be able to find people to write on economics who passed Econ 101.

Finally, the genuflecting about the lack of jobs is especially bizarre in the context of the news stories about the Federal Reserve Board being prepared to raise interest rates. The point of raising interest rates is to slow the economy and keep workers from getting jobs. So if we are worried that technology may be displacing workers, why doesn’t someone relay these concerns to the folks at the Fed so that they won’t aggrevate the problem by raising interest rates?

The NYT’s Upshot section ran a major piece headlined “as robots grow smarter, American workers struggle to keep up.” The gist of the piece is that robots are rapidly replacing workers, leading to a lack of jobs. The piece focuses on the drop in employment in the last decade, which it attributes to the spread of robotization and computer technology. It includes comments from several economists pontificating about the impact on the distribution of income.

If robots and computers are leading to the rapid displacement of workers, they are managing to keep it a secret from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). BLS actually measures the rate at which the economy is becoming more efficient through the use of things like robots and computers, it’s called “productivity growth.”

Fans of data know that, contrary to what you read in the NYT, productivity growth has actually been rather slow in recent years. In the last decade it has averaged less than 1.5 percent annually. By comparison, in the twenty six years from 1947 to 1973 productivity growth averaged 2.8 percent annually. Contrary to the concerns expressed in this article, the rapid spread of technology in that period was associated with low rates of unemployment and high rates of wage growth for the bulk of the population.

The more obvious reason for the drop in employment over the last decade is the loss of demand that resulted from the collapse of the housing bubble. (Did they miss this one at the NYT?) That happens to fit the data like a glove, unlike the speculation on productivity.

Also,if we are discussing demand and employment it is probably worth mentioning the trade deficit. This translates into more than $500 billion in lost annual demand (@ 3.0 percent of GDP). The trade deficit implies demand being created in Europe or Japan, not the United States.

What the hell is the problem with papers not being able to talk about the trade deficit, is there censorship on the topic? This is basic national income accounting. This means it is not an arguable point, those who don’t recognize the trade deficit as a drain on demand in the context of an economy that is below full employment (as discussed here) are simply wrong. The NYT should be able to find people to write on economics who passed Econ 101.

Finally, the genuflecting about the lack of jobs is especially bizarre in the context of the news stories about the Federal Reserve Board being prepared to raise interest rates. The point of raising interest rates is to slow the economy and keep workers from getting jobs. So if we are worried that technology may be displacing workers, why doesn’t someone relay these concerns to the folks at the Fed so that they won’t aggrevate the problem by raising interest rates?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I have often commented about the apparent difficulty of obtaining reliable information about the economy in downtown Washington, DC, as demonstrated by the news and reporting in the Washington Post. Michael Gerson gave us more evidence today in his column criticizing populism of the left and right. At one point he mocks Hilary Clinton for her populist rhetoric noting that her ties to Robert Rubin and concerns for the bond market make it unconvincing.

Gerson then adds:

“Some baggage can never be checked. And some of us find her past association with economic sanity to be reassuring.”

Of course what Gerson is describing as “economic sanity” are the policies that gave us massive trade deficits, and the stock and housing bubbles. These policies are likely to result in close to ten trillion in lost output over the first two decades of this century. They have resulted in millions of lost jobs and homes. It would difficult to find an example of more disastrous economic policies being pursued in any major developed country. Obviously, if Gerson was able to get data on the economy he would not be associating Robert Rubin’s policies with economic sanity.

I have often commented about the apparent difficulty of obtaining reliable information about the economy in downtown Washington, DC, as demonstrated by the news and reporting in the Washington Post. Michael Gerson gave us more evidence today in his column criticizing populism of the left and right. At one point he mocks Hilary Clinton for her populist rhetoric noting that her ties to Robert Rubin and concerns for the bond market make it unconvincing.

Gerson then adds:

“Some baggage can never be checked. And some of us find her past association with economic sanity to be reassuring.”

Of course what Gerson is describing as “economic sanity” are the policies that gave us massive trade deficits, and the stock and housing bubbles. These policies are likely to result in close to ten trillion in lost output over the first two decades of this century. They have resulted in millions of lost jobs and homes. It would difficult to find an example of more disastrous economic policies being pursued in any major developed country. Obviously, if Gerson was able to get data on the economy he would not be associating Robert Rubin’s policies with economic sanity.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post just hates, hates, hates the idea that ordinary workers (i.e. people who don’t earn six, seven, and eight figure salaries) should enjoy any job security. They took this hatred to Japan in their lead editorial, complaining that Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in a news conference following the re-election of his party pledged to pressure companies to raise wages. The Post told readers:

“a more effective, if less populist, action would be the passage of labor reforms to make hiring and firing easier.”

Clearly the Post is focused on the firing part of the picture. Since Abe took office, Japanese companies have had little problem hiring workers. The employment to population ratio has risen by two full percentage points in the less than two years since Abe took office. This would be comparable to an increase in employment in the United States of almost 5 million people. That is almost 1 million more than the job growth we have actually seen over this period.

Apparently the Post’s editors thought it would be too crude to just say that it should be easier for Japanese companies to fire workers so it added the comment on hiring to confuse the issue.

The Washington Post just hates, hates, hates the idea that ordinary workers (i.e. people who don’t earn six, seven, and eight figure salaries) should enjoy any job security. They took this hatred to Japan in their lead editorial, complaining that Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in a news conference following the re-election of his party pledged to pressure companies to raise wages. The Post told readers:

“a more effective, if less populist, action would be the passage of labor reforms to make hiring and firing easier.”

Clearly the Post is focused on the firing part of the picture. Since Abe took office, Japanese companies have had little problem hiring workers. The employment to population ratio has risen by two full percentage points in the less than two years since Abe took office. This would be comparable to an increase in employment in the United States of almost 5 million people. That is almost 1 million more than the job growth we have actually seen over this period.

Apparently the Post’s editors thought it would be too crude to just say that it should be easier for Japanese companies to fire workers so it added the comment on hiring to confuse the issue.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión