Donald Trump seems to have forgotten what the economy was like when he left office. He talks as though it was booming and then Biden sank it. In fact, the opposite is the case.

The economy took a massive hit in the spring of 2020 from pandemic shutdowns, while it did regain many of the lost jobs in the summer, momentum slowed sharply in the fall.

In the last three months of the Trump administration we were creating jobs at a rate of just 140,000 a month. We were still down 9.4 million jobs from the pre-pandemic level. At the Trump rate of job creation it would have taken us more than 5 ½ years to get back the jobs we lost in the pandemic.

The Biden recovery package hugely hastened the pace of job growth. In the first two years of the Biden administration we created jobs at a 555,000 monthly pace. We got back the jobs lost in the pandemic in less than a year and a half. This was far faster than almost anyone expected.

Trump also seems confused about the state of the economy before the pandemic. While the economy was healthy, there was nothing resembling a boom. Essentially it was just continuing the recovery that Obama had set in place after the Great Recession.

The monthly rate of job growth in the Trump administration, pre-pandemic, was actually somewhat lower than it had been in the last three years of the Obama administration. We created an average of 180,000 jobs a month under Trump before the pandemic. That compares to an average of 225,000 jobs a month in the last three years of the Obama administration.

That may look like a boom in Donald Trump’s head, but not in the real world. For completeness we can include in the chart the 349,000 monthly pace of job growth in the Biden administration through September of this year.

Donald Trump seems to have forgotten what the economy was like when he left office. He talks as though it was booming and then Biden sank it. In fact, the opposite is the case.

The economy took a massive hit in the spring of 2020 from pandemic shutdowns, while it did regain many of the lost jobs in the summer, momentum slowed sharply in the fall.

In the last three months of the Trump administration we were creating jobs at a rate of just 140,000 a month. We were still down 9.4 million jobs from the pre-pandemic level. At the Trump rate of job creation it would have taken us more than 5 ½ years to get back the jobs we lost in the pandemic.

The Biden recovery package hugely hastened the pace of job growth. In the first two years of the Biden administration we created jobs at a 555,000 monthly pace. We got back the jobs lost in the pandemic in less than a year and a half. This was far faster than almost anyone expected.

Trump also seems confused about the state of the economy before the pandemic. While the economy was healthy, there was nothing resembling a boom. Essentially it was just continuing the recovery that Obama had set in place after the Great Recession.

The monthly rate of job growth in the Trump administration, pre-pandemic, was actually somewhat lower than it had been in the last three years of the Obama administration. We created an average of 180,000 jobs a month under Trump before the pandemic. That compares to an average of 225,000 jobs a month in the last three years of the Obama administration.

That may look like a boom in Donald Trump’s head, but not in the real world. For completeness we can include in the chart the 349,000 monthly pace of job growth in the Biden administration through September of this year.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is more than a bit bizarre reading pieces that talk about automation or job-killing AI as something new and alien. These are forms of productivity growth. They allow more goods and services to be produced for each hour of human labor.

Productivity growth is usually thought of as a good thing. It’s the reason that we don’t have half the U.S. workforce employed in agriculture growing our food. Instead, it is around 1.0 percent of the U.S. workforce, and we grow enough to be huge food exporters.

Productivity growth allows for workers to have higher wages. The period in our history where we had the most rapid productivity growth was in the post-war boom from 1947 to 1973. Productivity growth averaged almost 3.0 percent a year. This was passed on in the form of higher real wages and improved benefits.

There is no guarantee that the benefits of productivity growth will be passed on to workers or shared evenly among workers. From 1980 to 2010, the bulk of the gains from higher productivity went to workers at the top end of the wage distribution (e.g. CEOs, Wall Street types, and doctors and dentists). The wages for workers at the middle and bottom barely kept pace with inflation.

In the last two decades there has been a shift from wages to profits. Workers at the middle and bottom have been seeing real wage gains over this period, but they have not kept pace with productivity growth.

Whether or not workers share in the gains from productivity growth depends on how we choose to structure the economy. If we run a high employment economy, as is now the case, workers are well-positioned to secure wage gains in line with productivity growth.

Also, strong unions make workers better positioned to secure wage gains. The strength of unions depends both on their organizing, but also the institutional structure. If employers are free to harass or fire workers trying to organize, unions will be weaker. The laws on what sort of strikes are allowed also affect workers’ power. For example, laws in the United States that prohibit one union from supporting another union’s strike (e.g. Teamsters refusing to deliver supplies to a hotel where the workers are striking) weaken workers’ power.

Other rules also indirectly have a large effect on distribution, such as the strong patent and copyright monopolies that the U.S. government hands out. Bankruptcy laws that make it easy for corporations or private equity companies to avoid debt, including pension liabilities to workers, also affect distribution.

Anyhow, this is a big topic (see Rigged, it’s free), but the idea that productivity growth would ever be the enemy is a bizarre one. Automation and other technologies with labor displacing potential are hardly new and there is zero reason for workers as a group to fear them, even though they may put specific jobs at risk.

The key issue is to structure the market to ensure that the benefits are broadly shared. We never have to worry about running out of jobs. We can always have people work shorter hours or just have the government send out checks to increase demand. It is unfortunate that many have sought to cultivate this phony fear.

It is more than a bit bizarre reading pieces that talk about automation or job-killing AI as something new and alien. These are forms of productivity growth. They allow more goods and services to be produced for each hour of human labor.

Productivity growth is usually thought of as a good thing. It’s the reason that we don’t have half the U.S. workforce employed in agriculture growing our food. Instead, it is around 1.0 percent of the U.S. workforce, and we grow enough to be huge food exporters.

Productivity growth allows for workers to have higher wages. The period in our history where we had the most rapid productivity growth was in the post-war boom from 1947 to 1973. Productivity growth averaged almost 3.0 percent a year. This was passed on in the form of higher real wages and improved benefits.

There is no guarantee that the benefits of productivity growth will be passed on to workers or shared evenly among workers. From 1980 to 2010, the bulk of the gains from higher productivity went to workers at the top end of the wage distribution (e.g. CEOs, Wall Street types, and doctors and dentists). The wages for workers at the middle and bottom barely kept pace with inflation.

In the last two decades there has been a shift from wages to profits. Workers at the middle and bottom have been seeing real wage gains over this period, but they have not kept pace with productivity growth.

Whether or not workers share in the gains from productivity growth depends on how we choose to structure the economy. If we run a high employment economy, as is now the case, workers are well-positioned to secure wage gains in line with productivity growth.

Also, strong unions make workers better positioned to secure wage gains. The strength of unions depends both on their organizing, but also the institutional structure. If employers are free to harass or fire workers trying to organize, unions will be weaker. The laws on what sort of strikes are allowed also affect workers’ power. For example, laws in the United States that prohibit one union from supporting another union’s strike (e.g. Teamsters refusing to deliver supplies to a hotel where the workers are striking) weaken workers’ power.

Other rules also indirectly have a large effect on distribution, such as the strong patent and copyright monopolies that the U.S. government hands out. Bankruptcy laws that make it easy for corporations or private equity companies to avoid debt, including pension liabilities to workers, also affect distribution.

Anyhow, this is a big topic (see Rigged, it’s free), but the idea that productivity growth would ever be the enemy is a bizarre one. Automation and other technologies with labor displacing potential are hardly new and there is zero reason for workers as a group to fear them, even though they may put specific jobs at risk.

The key issue is to structure the market to ensure that the benefits are broadly shared. We never have to worry about running out of jobs. We can always have people work shorter hours or just have the government send out checks to increase demand. It is unfortunate that many have sought to cultivate this phony fear.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The revisions to GDP data generally are not of much interest to anyone except a small group of economics nerds who follow the data closely. However, this year’s revisions are a big deal which should interest many people. Basically, they tell us a story of an economy that has performed substantially better since the pandemic than we had previously believed.

The highlights are:

There were also a couple of not-so-good items:

Faster GDP Growth

Starting with GDP growth, the revisions indicate that GDP grew a cumulative total of 1.3 percent more than previously reported. This puts cumulative GDP growth since the fourth quarter of 2019 at 10.7 percent.

By comparison, among the G-7 Italy comes in second with 5.1 percent cumulative growth, less than half of the U.S. growth. Japan comes next at 2.4 percent (less than one-fourth the U.S. rate) and at the rear are the U.K. at -0.9 percent, Germany at -1.8 percent, and Canada -3.0 percent.

The growth we have been seeing is even more than was predicted before the pandemic. At the start of 2020, CBO projected that the economy would grow 8.2 percent between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2024. The difference comes to almost $660 billion in annual output, or nearly $2,000 for every person in the country.

This means the economy under Biden-Harris has grown more rapidly than would have been expected if we had not had a worldwide pandemic. While the pandemic largely derailed growth in other major economies, it did not have that effect here. The performance since 2019 looks great by any measure, but especially if we grade on a curve.

A Productivity Speedup

Before the revisions, productivity growth averaged 1.6 percent from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the second quarter of 2024. This is slightly slower than in the four years just before the pandemic (fourth quarter of 2015 to fourth quarter of 2019), but considerably faster than the 1.1 percent average rate for the decade from the fourth quarter of 2009 to the fourth quarter of 2019.

While that story makes the case for a productivity uptick ambiguous, the picture will look much better when we factor in the effect of this revision, as well as the revision to employment growth reported last month. That revision implied that hours in the second quarter of 2024 were roughly 0.6 percent less than previously reported. With GDP now reported as being 1.3 percent higher, this means the level of productivity is roughly 1.9 percent higher in the second quarter of 2024 than is now reported. (The actual number will be somewhat different, since the calculations for both the numerator and denominator are somewhat more complicated than implied here.)

With these revisions, the average rate of productivity growth will come to roughly 2.0 percent in the years since the pandemic. This is a huge deal.

If we can sustain a 2.0 percent pace of productivity growth, it means that real wages can grow at a 2.0 percent annual rate without inflation or any erosion of profit shares (we will come back to this.) It also means that we can sustain 4.0 percent nominal wage growth, a somewhat faster pace than we are now seeing, and still hit the Fed’s 2.0 percent inflation target.

Faster productivity growth will also translate into faster GDP growth. If productivity grows 0.5 percentage points more rapidly than expected, then GDP will grow roughly 0.5 percentage points more than expected. This lowers the ratio of debt to GDP. If we sustain a 0.5 pp uptick in GDP growth for a decade, then GDP will be 5.0 percent higher ten years from now than if we didn’t have this uptick. This means, other things equal, the debt-to-GDP ratio will be 5.0 pp lower than we had expected.

For folks worried that our debt-to-GDP ratio is approaching a point where we are going to hit a crisis, this is very good news. It also is good news for those who would just rather not see such a large share of GDP handed out as interest payments on the debt.

Higher Income Growth Than We Had Thought

As noted, the revisions were larger on the income side than the output side. The cumulative revision to income was an increase of 3.8 percent. This meant both higher wages and higher profits than had previously been reported. Labor income was revised up by 1.5 percent compared to what had previously been reported. Profit income was revised up by an even larger amount, with the new figure 11.5 percent higher than the previously reported number.

There were also large revisions in percentage terms for income in proprietorships (mostly small businesses and professional practices), which were revised up by 5.4 percent. Income for farm proprietorships was revised up by an extraordinary 41.1 percent.

Saving Rate Was Revised Up

This is one outcome that was 100 percent predictable from the large statistical discrepancy (2.7 percent of GDP) between the output measure of GDP and the income side measure. These measures of GDP are defined as being equal. Revisions that moved the two measures closer together would either lower output, almost certainly meaning less consumption, or raise income, which would likely translate into higher disposable income. Either way, the saving rate would be revised upward.

That is exactly what happened in today’s report. The saving rate for the second quarter was revised up from 3.3 percent to 5.2 percent. That is somewhat below the 6.2 percent average in the four years before the pandemic, but not out of line with what we have seen in prior years. (The saving rate was 5.4 percent in 2016.)

This upward revision indicates that the whining seen in many news stories, about hard-pressed consumers being forced to draw down their savings, were not based in reality. The low saving rate reported in recent government releases was a measurement quirk, not something that existed in the world.

A Higher Profit Share

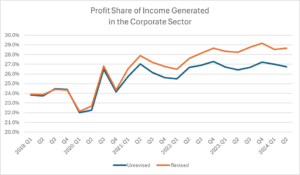

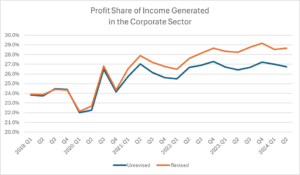

As has been widely noted, the profit share of income rose during the pandemic. This was most immediately attributed to the supply-chain problems during 2021-2022. However, as these problems receded into the past, many of us expected that the profit shares would revert to their pre-pandemic level. That does not seem to have happened.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and Author’s Calculations.

With the revised data the profit share is almost back to its post-pandemic peak. It stood at 28.7 percent in the second quarter. This is down by 0.5 percentage points from its peak of 29.2 percent in the fourth quarter, but still up by more than 4.0 percentage points from the 2019 level. (This figure subtracts out the profits earned by the Federal Reserve banks from total profits.)

While the cause of this rise can be debated, its existence cannot. Whether or not greater market power is the cause, there clearly is substantial room for wages to rise at the expense of profits, unless for some reason we think the 2019 profit share was unsustainably low.

A Lower Tax Share of Corporate Profits

One unheralded success of the Biden-Harris administration was an increase in the share of corporate profits collected in taxes. This has been falling for the last five decades, partly due to a reduction in tax rates by also as a result of increased avoidance and evasion. The tax share of corporate profits has increased in recent years, presumably mostly as a result of increased enforcement.

In 2019 the share of profits paid in taxes was just 15.3 percent. In the unrevised data, the share stood at 22.3 percent in the first half of 2024. In the revised data it is 20.3 percent. This is still a considerable gain from the 2019 share, with the tax take almost one-third higher when measured as a share of corporate profits.

The Good Economic Picture Looks Even Better with Revisions

In sum, an economic picture that already looked extremely impressive before the revisions looks even better with this presumably better data. Perhaps most importantly, we now have a better story to tell about an uptick in productivity growth. If this can be sustained, the future could be much brighter than prior projections implied.

The revisions to GDP data generally are not of much interest to anyone except a small group of economics nerds who follow the data closely. However, this year’s revisions are a big deal which should interest many people. Basically, they tell us a story of an economy that has performed substantially better since the pandemic than we had previously believed.

The highlights are:

There were also a couple of not-so-good items:

Faster GDP Growth

Starting with GDP growth, the revisions indicate that GDP grew a cumulative total of 1.3 percent more than previously reported. This puts cumulative GDP growth since the fourth quarter of 2019 at 10.7 percent.

By comparison, among the G-7 Italy comes in second with 5.1 percent cumulative growth, less than half of the U.S. growth. Japan comes next at 2.4 percent (less than one-fourth the U.S. rate) and at the rear are the U.K. at -0.9 percent, Germany at -1.8 percent, and Canada -3.0 percent.

The growth we have been seeing is even more than was predicted before the pandemic. At the start of 2020, CBO projected that the economy would grow 8.2 percent between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2024. The difference comes to almost $660 billion in annual output, or nearly $2,000 for every person in the country.

This means the economy under Biden-Harris has grown more rapidly than would have been expected if we had not had a worldwide pandemic. While the pandemic largely derailed growth in other major economies, it did not have that effect here. The performance since 2019 looks great by any measure, but especially if we grade on a curve.

A Productivity Speedup

Before the revisions, productivity growth averaged 1.6 percent from the fourth quarter of 2019 to the second quarter of 2024. This is slightly slower than in the four years just before the pandemic (fourth quarter of 2015 to fourth quarter of 2019), but considerably faster than the 1.1 percent average rate for the decade from the fourth quarter of 2009 to the fourth quarter of 2019.

While that story makes the case for a productivity uptick ambiguous, the picture will look much better when we factor in the effect of this revision, as well as the revision to employment growth reported last month. That revision implied that hours in the second quarter of 2024 were roughly 0.6 percent less than previously reported. With GDP now reported as being 1.3 percent higher, this means the level of productivity is roughly 1.9 percent higher in the second quarter of 2024 than is now reported. (The actual number will be somewhat different, since the calculations for both the numerator and denominator are somewhat more complicated than implied here.)

With these revisions, the average rate of productivity growth will come to roughly 2.0 percent in the years since the pandemic. This is a huge deal.

If we can sustain a 2.0 percent pace of productivity growth, it means that real wages can grow at a 2.0 percent annual rate without inflation or any erosion of profit shares (we will come back to this.) It also means that we can sustain 4.0 percent nominal wage growth, a somewhat faster pace than we are now seeing, and still hit the Fed’s 2.0 percent inflation target.

Faster productivity growth will also translate into faster GDP growth. If productivity grows 0.5 percentage points more rapidly than expected, then GDP will grow roughly 0.5 percentage points more than expected. This lowers the ratio of debt to GDP. If we sustain a 0.5 pp uptick in GDP growth for a decade, then GDP will be 5.0 percent higher ten years from now than if we didn’t have this uptick. This means, other things equal, the debt-to-GDP ratio will be 5.0 pp lower than we had expected.

For folks worried that our debt-to-GDP ratio is approaching a point where we are going to hit a crisis, this is very good news. It also is good news for those who would just rather not see such a large share of GDP handed out as interest payments on the debt.

Higher Income Growth Than We Had Thought

As noted, the revisions were larger on the income side than the output side. The cumulative revision to income was an increase of 3.8 percent. This meant both higher wages and higher profits than had previously been reported. Labor income was revised up by 1.5 percent compared to what had previously been reported. Profit income was revised up by an even larger amount, with the new figure 11.5 percent higher than the previously reported number.

There were also large revisions in percentage terms for income in proprietorships (mostly small businesses and professional practices), which were revised up by 5.4 percent. Income for farm proprietorships was revised up by an extraordinary 41.1 percent.

Saving Rate Was Revised Up

This is one outcome that was 100 percent predictable from the large statistical discrepancy (2.7 percent of GDP) between the output measure of GDP and the income side measure. These measures of GDP are defined as being equal. Revisions that moved the two measures closer together would either lower output, almost certainly meaning less consumption, or raise income, which would likely translate into higher disposable income. Either way, the saving rate would be revised upward.

That is exactly what happened in today’s report. The saving rate for the second quarter was revised up from 3.3 percent to 5.2 percent. That is somewhat below the 6.2 percent average in the four years before the pandemic, but not out of line with what we have seen in prior years. (The saving rate was 5.4 percent in 2016.)

This upward revision indicates that the whining seen in many news stories, about hard-pressed consumers being forced to draw down their savings, were not based in reality. The low saving rate reported in recent government releases was a measurement quirk, not something that existed in the world.

A Higher Profit Share

As has been widely noted, the profit share of income rose during the pandemic. This was most immediately attributed to the supply-chain problems during 2021-2022. However, as these problems receded into the past, many of us expected that the profit shares would revert to their pre-pandemic level. That does not seem to have happened.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis and Author’s Calculations.

With the revised data the profit share is almost back to its post-pandemic peak. It stood at 28.7 percent in the second quarter. This is down by 0.5 percentage points from its peak of 29.2 percent in the fourth quarter, but still up by more than 4.0 percentage points from the 2019 level. (This figure subtracts out the profits earned by the Federal Reserve banks from total profits.)

While the cause of this rise can be debated, its existence cannot. Whether or not greater market power is the cause, there clearly is substantial room for wages to rise at the expense of profits, unless for some reason we think the 2019 profit share was unsustainably low.

A Lower Tax Share of Corporate Profits

One unheralded success of the Biden-Harris administration was an increase in the share of corporate profits collected in taxes. This has been falling for the last five decades, partly due to a reduction in tax rates by also as a result of increased avoidance and evasion. The tax share of corporate profits has increased in recent years, presumably mostly as a result of increased enforcement.

In 2019 the share of profits paid in taxes was just 15.3 percent. In the unrevised data, the share stood at 22.3 percent in the first half of 2024. In the revised data it is 20.3 percent. This is still a considerable gain from the 2019 share, with the tax take almost one-third higher when measured as a share of corporate profits.

The Good Economic Picture Looks Even Better with Revisions

In sum, an economic picture that already looked extremely impressive before the revisions looks even better with this presumably better data. Perhaps most importantly, we now have a better story to tell about an uptick in productivity growth. If this can be sustained, the future could be much brighter than prior projections implied.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

We know that most people say that they think the economy has performed poorly under the Biden-Harris administration. However, we also know that by standard economic measures, the administration has been an incredible success story.

We saw the longest stretch of low unemployment in 70 years. Unemployment rates for Blacks, Black teens, and Hispanics all hit or tied record lows. While taking a dip in 2021-2022, real wages have bounced back and are above their pre-pandemic peaks, especially for workers at the bottom end of the wage distribution.

There has been a record pace of new business formation. Workers report record high levels of workplace satisfaction. The number of workers who can work from home has increased by almost 20 million. And more than 14 million homeowners were able to refinance their mortgages, either getting cash out for other purposes or saving thousands of dollars a year on interest payments.

This was in spite of a worldwide pandemic that initially sent employment plummeting, and then inflation soaring, as supply chain bottlenecks created shortages of many goods. The US recovery has been by far the strongest of any wealthy country, and its inflation rate by many measures is now below the average for other rich countries.

That story should give the Biden-Harris administration much to boast about in discussing its economic record, However, this is not the case. We can debate how much the media have contributed to this negative assessment, but there are any number of cases where they have reported things that are either simply not true or sufficiently distorted that they give people an entirely inaccurate picture of the state of the economy.

Since I have nothing else to do this fine Monday afternoon in Astoria, I thought I would go through my six favorites.

Number 1: The New York Times Picks an Atypical Worker to Tell a Story About a Divided Economy.

This one was really mindboggling to me. The piece is headlined “America’s Divided Summer Economy is Coming to an Airport or Hotel Near You.” The subhead pressed the case further, telling us, “The gulf between higher- and low-income consumers has been widening for years, but it is expected to show up clearly in this travel season.”

The problem is that this story is 180 degrees at odds with reality. The fastest wage growth in this recovery has been at the bottom of wage distribution, with workers in the bottom decile seeing wage gains that outpaced inflation since the pandemic by more than 13.0 percent. Workers in second quintile (going from the 20th to the 40th percentile of the wage distribution) saw real wage gains of 5.0 percent compared to 2019.

So how does the New York Times deal with a reality that is directly at odds with the story it wants to tell readers? It finds an atypical low-wage worker to profile as a representative of the low-wage economy more generally:

“Recent economic trends could exacerbate that. Lashonda Barber, an airport worker in Charlotte, N.C., is among those feeling the pinch. She will spend her summer on planes, but she won’t be leaving the airport for vacation.

“Ms. Barber, 42, makes $19 per hour, 40 hours per week, driving a trash truck that cleans up after international flights. It is a difficult position: The tarmac is sweltering in the Southern summer sun; the rubbish bags are heavy. And while it’s poised to be a busy summer, Ms. Barber’s job is increasingly failing to pay the bills. Both prices and her home taxes are up notably, but she is making just $1 an hour more than she was when she started the gig five years ago.”

As I noted when I wrote this piece up two months ago:

For a typical worker at Ms. Barber’s point in the income distribution, nominal wages (before adjusting for inflation) rose 30.4 percent over the last five years. This means that if she were representative of this group of workers, she would have seen a pay hike of around $5.40 an hour rather than the $1.00 increase reported in the article.

Incredibly, the article actually acknowledged this point.

“While that is not the standard experience — overall, wages for lower-income people have grown faster than inflation since at least late 2022 — it is a reminder that behind the averages, some people are falling behind.”

So, the New York Times deliberately found a worker who it recognized was atypical in order to tell a story about the low-wage workforce more generally that it knew was not true? What the fuck?

You can see why this gets the number 1 position on my list.

Number 2: It’s Hard for Recent College Grads to Find Jobs Even When Their Unemployment Rate is Near a Twenty-Year Low.

This one is delicious both because the theme is so obviously wrong and the error proved to be contagious. It started with a New York Times column titled “Why Can’t College Grads Find Jobs? Here Are Some Theories — and Fixes.”

The problem with the column is that it is reporting on research that finds that unemployed recent graduates have a hard time finding jobs, not recent college graduates in general. The overwhelming majority of recent college graduates are not unemployed, so this piece is telling us about the experience of a small minority of recent grads and telling us that the problem of high unemployment applies to the group as a whole.

If we look at the situation of recent college grads as a whole, it is 180 degrees at odds with what the column told readers. The unemployment rate for college grads between the ages of 21 and 24 had been below its pre-pandemic low-point, although it has inched up in recent months. Nonetheless, it is still near twenty-year lows, which makes a column telling us it is difficult for young college grads to get jobs rather odd.

Strikingly, this tidbit of misinformation spread to the Washington Post. Less than two weeks later it ran a news piece headlined, “Degree? Yes. Job? Maybe Not Yet.”

In spite of its headline, this piece was clearer that the problem was the re-employment of workers who report being unemployed. It noted that the unemployment rate for young college grads was 4.3 percent, which is pretty low by almost any measure.

Number 3: The Two-Full Time Job Measure of Economic Hardship

This was another gem of misinterpretation which also became contagious. The Washington Post discovered in the summer of 2022 that a record number of people reported working two full-time jobs. (A job is classified as full-time if it is more than 34 hours a week.) It decided that this was an important measure of economic hardship, since it meant that people had to work two full-time jobs to make ends meet.

There were three big problems with this new measure of hardship. The first is that it only applied to a tiny share of the workforce. Even at the all-time high reached that summer, we were only talking about 426,000 people, or 0.26 percent of the workforce.

The second problem is that if we looked at this number as share of employment, it was not a record high. There were other points in the past where it was almost exactly as high, and one time where it was clearly higher. That undermines the crisis story.

The third and most important problem is the time when the share of people working two full-time jobs hits its peak was July of 2000. This was at the peak of the 1990s Internet boom., which was widely viewed as the economy’s most prosperous period in the last half century.

Ironically, rather than being a sign of a bad economy, it looks like this measure is actually pro-cyclical. The number of people with two full-time jobs rises when the economy is healthy. We also saw peaks comparable to the 2022 level in 2018 – near the peak of the last business cycle – and in 2006, before the housing bubble burst and we got the Great Recession. It seems that the reason these people are working two full-time jobs is because they have the option to do so, which is apparently easier when the economy is strong than when it isn’t.

This confusion spread to Marketplace Radio the following week. It also reported on the large number of people holding two full-time jobs as evidence of economic hardship.

Number 4: The Retirement Crisis

The run-up in the stock market and house prices has meant that people approaching retirement have far more wealth than they did before the pandemic. According to the Federal Reserve Board, the median wealth of near retirees, people between the ages of 55 and 65, is more than 45 percent higher in 2022 than it was in 2019. (The survey is only done every three years. With the further rise in the stock market, the gains since 2019 would be even larger.)

This reality didn’t prevent CNN from doing a major piece on the retirement crisis. To be clear, there are millions of older workers who are poorly prepared for retirement. However, this number is almost certainly considerably lower than it had been before the pandemic when CNN was not warning about a retirement crisis.

Number 5: The Collapsing Saving Rate

One line that has been repeated in a number of places is the sharp decline in the saving rate, which is supposedly because people are having trouble making ends meet. Marketplace Radio gave us a recent example. The problem with this story is that it is driven by measurement error, as I explained on Beat the Press.

We have a gap of 2.7 percentage points of GDP between the output side measure and income side measure. These are definitionally equal, so this extraordinarily large gap can only be due to measurement error.

While I have no idea which side is closer to the mark, either a downward revision to output or an upward revision to income will almost certainly mean a rise in the saving rate. On the output side, a downward revision almost guarantees less consumption since it is 70 percent of output.

If the income side is revised up, then it almost certainly means more income. Since saving is defined as disposable income minus consumption, an upward revision to income would also mean a higher saving rate.

This means that however the statistical discrepancy is resolved, it will increase the saving rate. The amount at stake is large enough to bring it back to its pre-pandemic level. In other words, the idea that savings are falling because hard-pressed families can’t make ends meet is one more bad economy story that doesn’t correspond to reality.

Number 6 : Young People Will Never Be Able to Own a Home

There has been an endless stream of articles and news stories telling us the sad news that many young people have given up on the idea that they can ever share in the American dream and own a home. They were very touching – and also completely unconnected to reality.

Homeownership rates for households under the age of 35 actually rose in the pandemic. People with cash from pandemic payments, and relatively secure employment once the Biden recovery package kickstarted the economy, bought homes in large numbers.

The ownership rate for this group peaked at 37.6 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019. It had risen to 39.3 percent by the third quarter of 2022. At that point higher house prices and the surge in mortgage rates began to push the ownership rate down. However, even in the second quarter of this year it was 37.4 percent, which is higher than for any full year since the collapse of the housing bubble.

Furthermore, virtually no one expects mortgage rates to stay at their peaks (they have already come down by more than 1.5 percentage points), so writing news stories that seem to imply high mortgage rates in perpetuity was incredibly irresponsible. No one did this in the 1980s inflation era, when mortgage rates soared to more than 18.5 percent. It’s hard to understand why so many reporters seemed to think it was reasonable to make this blatantly unreasonable assumption about the future course of mortgage rates now.

The Big Six and the Endless Tales of the Bad Economy

Those are my six favorites, but I could come up with endless more pieces, like the CNN story on the family that drank massive amounts of milk who suffered horribly when milk prices rose, or the New York Times piece on a guy who used an incredible amount of gas and was being bankrupted by the record gas prices following the economy’s reopening.

There are also the stories that the media chose to ignore, like the record pace of new business starts, the people getting big pay increases in low-paying jobs, the record level of job satisfaction, the enormous savings in commuting costs and travel time for the additional 19 million people working from home (almost one eight of the workforce).

The media decided that they wanted to tell a bad economy story, and they were not going to let reality get in the way. People can speculate about motives, but the evidence speaks for itself. (I make this argument in a bit more length in a recent New Republic piece.)

We know that most people say that they think the economy has performed poorly under the Biden-Harris administration. However, we also know that by standard economic measures, the administration has been an incredible success story.

We saw the longest stretch of low unemployment in 70 years. Unemployment rates for Blacks, Black teens, and Hispanics all hit or tied record lows. While taking a dip in 2021-2022, real wages have bounced back and are above their pre-pandemic peaks, especially for workers at the bottom end of the wage distribution.

There has been a record pace of new business formation. Workers report record high levels of workplace satisfaction. The number of workers who can work from home has increased by almost 20 million. And more than 14 million homeowners were able to refinance their mortgages, either getting cash out for other purposes or saving thousands of dollars a year on interest payments.

This was in spite of a worldwide pandemic that initially sent employment plummeting, and then inflation soaring, as supply chain bottlenecks created shortages of many goods. The US recovery has been by far the strongest of any wealthy country, and its inflation rate by many measures is now below the average for other rich countries.

That story should give the Biden-Harris administration much to boast about in discussing its economic record, However, this is not the case. We can debate how much the media have contributed to this negative assessment, but there are any number of cases where they have reported things that are either simply not true or sufficiently distorted that they give people an entirely inaccurate picture of the state of the economy.

Since I have nothing else to do this fine Monday afternoon in Astoria, I thought I would go through my six favorites.

Number 1: The New York Times Picks an Atypical Worker to Tell a Story About a Divided Economy.

This one was really mindboggling to me. The piece is headlined “America’s Divided Summer Economy is Coming to an Airport or Hotel Near You.” The subhead pressed the case further, telling us, “The gulf between higher- and low-income consumers has been widening for years, but it is expected to show up clearly in this travel season.”

The problem is that this story is 180 degrees at odds with reality. The fastest wage growth in this recovery has been at the bottom of wage distribution, with workers in the bottom decile seeing wage gains that outpaced inflation since the pandemic by more than 13.0 percent. Workers in second quintile (going from the 20th to the 40th percentile of the wage distribution) saw real wage gains of 5.0 percent compared to 2019.

So how does the New York Times deal with a reality that is directly at odds with the story it wants to tell readers? It finds an atypical low-wage worker to profile as a representative of the low-wage economy more generally:

“Recent economic trends could exacerbate that. Lashonda Barber, an airport worker in Charlotte, N.C., is among those feeling the pinch. She will spend her summer on planes, but she won’t be leaving the airport for vacation.

“Ms. Barber, 42, makes $19 per hour, 40 hours per week, driving a trash truck that cleans up after international flights. It is a difficult position: The tarmac is sweltering in the Southern summer sun; the rubbish bags are heavy. And while it’s poised to be a busy summer, Ms. Barber’s job is increasingly failing to pay the bills. Both prices and her home taxes are up notably, but she is making just $1 an hour more than she was when she started the gig five years ago.”

As I noted when I wrote this piece up two months ago:

For a typical worker at Ms. Barber’s point in the income distribution, nominal wages (before adjusting for inflation) rose 30.4 percent over the last five years. This means that if she were representative of this group of workers, she would have seen a pay hike of around $5.40 an hour rather than the $1.00 increase reported in the article.

Incredibly, the article actually acknowledged this point.

“While that is not the standard experience — overall, wages for lower-income people have grown faster than inflation since at least late 2022 — it is a reminder that behind the averages, some people are falling behind.”

So, the New York Times deliberately found a worker who it recognized was atypical in order to tell a story about the low-wage workforce more generally that it knew was not true? What the fuck?

You can see why this gets the number 1 position on my list.

Number 2: It’s Hard for Recent College Grads to Find Jobs Even When Their Unemployment Rate is Near a Twenty-Year Low.

This one is delicious both because the theme is so obviously wrong and the error proved to be contagious. It started with a New York Times column titled “Why Can’t College Grads Find Jobs? Here Are Some Theories — and Fixes.”

The problem with the column is that it is reporting on research that finds that unemployed recent graduates have a hard time finding jobs, not recent college graduates in general. The overwhelming majority of recent college graduates are not unemployed, so this piece is telling us about the experience of a small minority of recent grads and telling us that the problem of high unemployment applies to the group as a whole.

If we look at the situation of recent college grads as a whole, it is 180 degrees at odds with what the column told readers. The unemployment rate for college grads between the ages of 21 and 24 had been below its pre-pandemic low-point, although it has inched up in recent months. Nonetheless, it is still near twenty-year lows, which makes a column telling us it is difficult for young college grads to get jobs rather odd.

Strikingly, this tidbit of misinformation spread to the Washington Post. Less than two weeks later it ran a news piece headlined, “Degree? Yes. Job? Maybe Not Yet.”

In spite of its headline, this piece was clearer that the problem was the re-employment of workers who report being unemployed. It noted that the unemployment rate for young college grads was 4.3 percent, which is pretty low by almost any measure.

Number 3: The Two-Full Time Job Measure of Economic Hardship

This was another gem of misinterpretation which also became contagious. The Washington Post discovered in the summer of 2022 that a record number of people reported working two full-time jobs. (A job is classified as full-time if it is more than 34 hours a week.) It decided that this was an important measure of economic hardship, since it meant that people had to work two full-time jobs to make ends meet.

There were three big problems with this new measure of hardship. The first is that it only applied to a tiny share of the workforce. Even at the all-time high reached that summer, we were only talking about 426,000 people, or 0.26 percent of the workforce.

The second problem is that if we looked at this number as share of employment, it was not a record high. There were other points in the past where it was almost exactly as high, and one time where it was clearly higher. That undermines the crisis story.

The third and most important problem is the time when the share of people working two full-time jobs hits its peak was July of 2000. This was at the peak of the 1990s Internet boom., which was widely viewed as the economy’s most prosperous period in the last half century.

Ironically, rather than being a sign of a bad economy, it looks like this measure is actually pro-cyclical. The number of people with two full-time jobs rises when the economy is healthy. We also saw peaks comparable to the 2022 level in 2018 – near the peak of the last business cycle – and in 2006, before the housing bubble burst and we got the Great Recession. It seems that the reason these people are working two full-time jobs is because they have the option to do so, which is apparently easier when the economy is strong than when it isn’t.

This confusion spread to Marketplace Radio the following week. It also reported on the large number of people holding two full-time jobs as evidence of economic hardship.

Number 4: The Retirement Crisis

The run-up in the stock market and house prices has meant that people approaching retirement have far more wealth than they did before the pandemic. According to the Federal Reserve Board, the median wealth of near retirees, people between the ages of 55 and 65, is more than 45 percent higher in 2022 than it was in 2019. (The survey is only done every three years. With the further rise in the stock market, the gains since 2019 would be even larger.)

This reality didn’t prevent CNN from doing a major piece on the retirement crisis. To be clear, there are millions of older workers who are poorly prepared for retirement. However, this number is almost certainly considerably lower than it had been before the pandemic when CNN was not warning about a retirement crisis.

Number 5: The Collapsing Saving Rate

One line that has been repeated in a number of places is the sharp decline in the saving rate, which is supposedly because people are having trouble making ends meet. Marketplace Radio gave us a recent example. The problem with this story is that it is driven by measurement error, as I explained on Beat the Press.

We have a gap of 2.7 percentage points of GDP between the output side measure and income side measure. These are definitionally equal, so this extraordinarily large gap can only be due to measurement error.

While I have no idea which side is closer to the mark, either a downward revision to output or an upward revision to income will almost certainly mean a rise in the saving rate. On the output side, a downward revision almost guarantees less consumption since it is 70 percent of output.

If the income side is revised up, then it almost certainly means more income. Since saving is defined as disposable income minus consumption, an upward revision to income would also mean a higher saving rate.

This means that however the statistical discrepancy is resolved, it will increase the saving rate. The amount at stake is large enough to bring it back to its pre-pandemic level. In other words, the idea that savings are falling because hard-pressed families can’t make ends meet is one more bad economy story that doesn’t correspond to reality.

Number 6 : Young People Will Never Be Able to Own a Home

There has been an endless stream of articles and news stories telling us the sad news that many young people have given up on the idea that they can ever share in the American dream and own a home. They were very touching – and also completely unconnected to reality.

Homeownership rates for households under the age of 35 actually rose in the pandemic. People with cash from pandemic payments, and relatively secure employment once the Biden recovery package kickstarted the economy, bought homes in large numbers.

The ownership rate for this group peaked at 37.6 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019. It had risen to 39.3 percent by the third quarter of 2022. At that point higher house prices and the surge in mortgage rates began to push the ownership rate down. However, even in the second quarter of this year it was 37.4 percent, which is higher than for any full year since the collapse of the housing bubble.

Furthermore, virtually no one expects mortgage rates to stay at their peaks (they have already come down by more than 1.5 percentage points), so writing news stories that seem to imply high mortgage rates in perpetuity was incredibly irresponsible. No one did this in the 1980s inflation era, when mortgage rates soared to more than 18.5 percent. It’s hard to understand why so many reporters seemed to think it was reasonable to make this blatantly unreasonable assumption about the future course of mortgage rates now.

The Big Six and the Endless Tales of the Bad Economy

Those are my six favorites, but I could come up with endless more pieces, like the CNN story on the family that drank massive amounts of milk who suffered horribly when milk prices rose, or the New York Times piece on a guy who used an incredible amount of gas and was being bankrupted by the record gas prices following the economy’s reopening.

There are also the stories that the media chose to ignore, like the record pace of new business starts, the people getting big pay increases in low-paying jobs, the record level of job satisfaction, the enormous savings in commuting costs and travel time for the additional 19 million people working from home (almost one eight of the workforce).

The media decided that they wanted to tell a bad economy story, and they were not going to let reality get in the way. People can speculate about motives, but the evidence speaks for itself. (I make this argument in a bit more length in a recent New Republic piece.)

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Matt Yglesias had a Twitter comment that got me thinking. He noted that most people are opposed to Donald Trump’s re-election. But he also pointed to polls showing that an overwhelming majority of the public supports mass deportation, the leading plank in his platform. He then conjectured that most people would not actually like the policy in practice.

I think Matt is right about this, but the implication here is that the vast majority of people support a policy they do not understand at all. That seems likely to be true, but it is worth asking how most people can have no idea of the meaning of the main policy plank of one of two major party presidential candidates. Rather than just laughing at the public’s ignorance, we might try asking how your typical person, with a full-time job, and possibly raising kids and other responsibilities, would have a clear idea of what mass deportation means?

It’s probably safe to assume that they have not been reading up on the nation’s immigrant population. They don’t have a clear idea of who they are, what they do, or even how many of them there are.

Donald Trump tells us that they are all drug dealers, murderers, and rapists, released from the prisons of Venezuela and other countries on the condition they come to America. He also says there are 20 million of them.

Many people probably don’t realize that the overwhelming majority of the people Trump wants to deport are doing difficult and often dangerous jobs that most native-born citizens would not want. Very few of them had criminal records in their home countries and they are in fact less likely to commit crimes here.

Also, most estimates put the number of unauthorized immigrants in the range of 10-12 million, although Trump’s VP pick, JD Vance, said they might look to deport people here legally as well, so it’s possible they could get to their 20 million number. This is made more likely given the fact that the Republican justices on the Supreme Court have shown a great willingness to defer to Trump even when it goes against past precedent or the wording of the Constitution.

Anyhow, the process of rounding up 10-20 million people would likely be incredibly expensive and violent. People who risked their lives going through dangerous jungles to come here are not likely to turn themselves in to be deported. Also, many have friends and relatives who are legally here and often citizens. They have the 2nd Amendment right to own and carry guns.

If we did succeed in rounding up this massive number of people, most of whom are workers, it would lead to a big jump in food prices and the cost of building new housing, since a large share of these people work in farms and food processing plants and in the construction industry. This means mass deportation would virtually guarantee higher prices at the grocery store and higher housing costs in the future, pushing up inflation, the other leading issue in this election. Most people likely do not understand this fact.

I have no idea what a genuine effort at mass deportation of this magnitude would look like, and I suspect few others do either. But since we may see a mass deportation if Donald Trump gets elected, it might be worth some major stories on the national news and in the New York Times, Washington Post and other major news outlets. That way people would at least have some sense of the meaning of the most important plank in Donald Trump’s platform.

And the great thing from the standpoint of the media is that they can run a version of this story again and again. Needless to say, if NBC, ABC, and others run a piece once, most people will still not have a clear idea of what mass deportation means. This means that if they run slightly modified versions the next day and the day after, and the week after. It would still be news for much of their audience. This way they can both inform the public and get many many news stories out of one body of research. That seems like a clear winner both in terms of newsroom economics and informing the public if they see this as their responsibility.

Matt Yglesias had a Twitter comment that got me thinking. He noted that most people are opposed to Donald Trump’s re-election. But he also pointed to polls showing that an overwhelming majority of the public supports mass deportation, the leading plank in his platform. He then conjectured that most people would not actually like the policy in practice.

I think Matt is right about this, but the implication here is that the vast majority of people support a policy they do not understand at all. That seems likely to be true, but it is worth asking how most people can have no idea of the meaning of the main policy plank of one of two major party presidential candidates. Rather than just laughing at the public’s ignorance, we might try asking how your typical person, with a full-time job, and possibly raising kids and other responsibilities, would have a clear idea of what mass deportation means?

It’s probably safe to assume that they have not been reading up on the nation’s immigrant population. They don’t have a clear idea of who they are, what they do, or even how many of them there are.

Donald Trump tells us that they are all drug dealers, murderers, and rapists, released from the prisons of Venezuela and other countries on the condition they come to America. He also says there are 20 million of them.

Many people probably don’t realize that the overwhelming majority of the people Trump wants to deport are doing difficult and often dangerous jobs that most native-born citizens would not want. Very few of them had criminal records in their home countries and they are in fact less likely to commit crimes here.

Also, most estimates put the number of unauthorized immigrants in the range of 10-12 million, although Trump’s VP pick, JD Vance, said they might look to deport people here legally as well, so it’s possible they could get to their 20 million number. This is made more likely given the fact that the Republican justices on the Supreme Court have shown a great willingness to defer to Trump even when it goes against past precedent or the wording of the Constitution.

Anyhow, the process of rounding up 10-20 million people would likely be incredibly expensive and violent. People who risked their lives going through dangerous jungles to come here are not likely to turn themselves in to be deported. Also, many have friends and relatives who are legally here and often citizens. They have the 2nd Amendment right to own and carry guns.

If we did succeed in rounding up this massive number of people, most of whom are workers, it would lead to a big jump in food prices and the cost of building new housing, since a large share of these people work in farms and food processing plants and in the construction industry. This means mass deportation would virtually guarantee higher prices at the grocery store and higher housing costs in the future, pushing up inflation, the other leading issue in this election. Most people likely do not understand this fact.

I have no idea what a genuine effort at mass deportation of this magnitude would look like, and I suspect few others do either. But since we may see a mass deportation if Donald Trump gets elected, it might be worth some major stories on the national news and in the New York Times, Washington Post and other major news outlets. That way people would at least have some sense of the meaning of the most important plank in Donald Trump’s platform.

And the great thing from the standpoint of the media is that they can run a version of this story again and again. Needless to say, if NBC, ABC, and others run a piece once, most people will still not have a clear idea of what mass deportation means. This means that if they run slightly modified versions the next day and the day after, and the week after. It would still be news for much of their audience. This way they can both inform the public and get many many news stories out of one body of research. That seems like a clear winner both in terms of newsroom economics and informing the public if they see this as their responsibility.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post gave us one of its standard deficit scold pieces yesterday. As we know, the Washington Post editorial board is absolutely the most serious of the “very serious people.” They are always worried about the debt and deficit. So, let’s have a little fun with the folks.

First, we can deal with the issue of whether the deficit is too large. There is a pretty simple answer to that. Is there any evidence that it is driving inflation?

If we were back in 2021-2022 when we had serious supply constraints because of the pandemic, the Post would have a pretty good case that the deficit was contributing to inflation. However, it is much harder to make that case now. Inflation has been slowing for the last year and a half and is now almost back to the Fed’s 2.0 percent target. In fact, if we exclude housing, which lags the market, CPI inflation would be just over 1.0 percent for the last year.

High interest rates are playing a role in slowing growth, so we can argue that we could have lower rates with a lower deficit, but we can also have lower rates with the current deficit, as the Fed will tell us tomorrow. It’s also worth noting the current 3.65 percent interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is lower than the rate at any point in the late 1990s when we were running budget surpluses.

In short, perhaps the Fed would give us somewhat lower interest rates if we knocked a few hundred billion off the deficit, but it’s not clear that a 0.1-0.2 percentage point drop in rates would be any big deal from the standpoint of benefitting the economy.

Then we have the issue of the debt. Yes, this is growing, but interestingly, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the long-term picture actually looks slightly better today than it did before the pandemic. The main reason is that CBO now projects healthcare costs will grow at a slower pace than they had projected in 2020.

This is noteworthy for two reasons. There has been a sharp slowing in health care costs since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). As a result, we are spending hundreds of billions a year less, saving more than $3000 per family, than had been projected before the bill was passed.

The other reason this is noteworthy is that we would have close to a balanced budget if our per capita health care costs were comparable to what other wealthy countries pay. While our system has become less wasteful over the last fifteen years, we still spend close to twice as much per person as people in other wealthy countries. There is plenty of waste that can still be wrung out of our healthcare system.

There are two questions to address on the debt. The first is the issue of whether we will face a crisis from the debt-to-GDP ratio getting too high.

The key point on this one is that we have been here before. During the Great Recession, two Harvard economics professors became international celebrities with a paper that purported to show that GDP growth slows sharply when the ratio of the national debt to income exceeds 90 percent. This paper was used as a rationale for austerity in the U.S., the EU, and elsewhere.

It turned out that the main result in the paper was driven by an Excel spreadsheet error. When this was corrected, their 90 percent threshold disappeared.

While others have argued that there is still some crisis threshold, it is not clear why that would be the case. If the United States has a healthy economy, with strong growth and moderate rates of inflation, it is not clear why we would ever face a crisis of investors being unwilling to buy U.S. government debt. Also, as many have noted the Federal Reserve Board can always buy debt if there are few buyers in private markets.

If we were facing a real economic crisis, say plummeting output due to war or climate-related factors, that would be a path towards runaway inflation, but in that case the problem would be the war or the climate-related factors, not the debt. The point here is that our priority should be maintaining a strong economy and then we won’t have to worry about the debt-to-GDP ratio getting too high.

Also, if the economy is growing rapidly, then the debt-to-GDP ratio will be growing less rapidly or even shrinking. That is the story of the drop in the debt to GDP ratio from 116 percent at the end of World War II to less than 40 percent by 1980. The government ran deficits almost every year during this period, but strong growth reduced the ratio of debt-to-GDP.

The other issue with the debt-to-GDP is the interest burden on the debt. We will spend almost $900 billion this year (3.1 percent of GDP) on interest. This is a lot of money that could be better spent on childcare, housing, or in many other areas. But it takes many years of serious austerity before we can make much of a dent in these interest payments.

Furthermore, there is little reason to believe that we are up against hard budget constraints if we want to spend more in these areas now. In other words, if we had the political will to spend another $50 or $100 billion a year on a child tax credit or some other worthwhile program, we could do it even without some offsetting tax increase or budget cut.

Government-Granted Patent and Copyright Monopolies

The other point worth making about the concern over interest payments is that it is very selective. One way the government pays for goods and services is by writing checks. We spend cash and directly add to the deficit and debt. However, the government also pays for a lot of things by granting patent and copyright monopolies. This is the way in which the government pays for innovation in most areas as well as a wide variety of creative work.

The rents from patent and copyright monopolies are huge, almost certainly much larger than the interest we pay each year on the government debt. In the case of prescription drugs alone they likely come to over $500 billion a year. If you add in the additional spending on medical equipment, computers, software and other items we are likely well over $1 trillion annually.

For some reason the Washington Post literally never talks about the burdens created by these government-granted monopolies. The decision to endlessly whine about interest burdens on the debt, but to ignore the much larger amounts paid each year in patent and copyright rents, is a political one. The Post will have to give its own explanation for this call, but it is important for the rest of us to recognize that we routinely ignore these burdens that we are handing down to our children.

Taxing Returns to Shareholders Instead of Profits

It’s also worth noting that if we want to raise more revenue there is an easy route that even the Washington Post editorial board should like, if they are being honest in their professed concerns. While the nominal corporate tax rate is 21 percent, we actually collect much less revenue than this tax rate would imply. This is because corporations have become experts at finding ways to avoid or evade the corporate income tax.

There is a way to circumvent their scheming and wipe out the tax gaming industry. We can switch the basis for the corporate income tax from profits to returns to shareholders (dividends plus capital gains). The advantage of this switch is that the amount that companies pay out in dividends and how much their stock appreciates are factors that are completely transparent. They can be found on dozens of financial websites. By contrast, corporate accountants tell us what corporate profits are.

We can set whatever tax rate Congress considers appropriate, but if it is applied to returns to shareholders, we can be sure that the IRS will actually get it. And by putting the tax gaming industry out of business, we will be freeing up resources (labor and capital) that can instead be used in something productive.

If the Washington Post wants to actually be serious, instead of just giving us the same old deficit hawk schtick, it could promote the idea of taxing stock returns. The tax on share buybacks was a useful first step. But don’t hold your breath.

The Washington Post gave us one of its standard deficit scold pieces yesterday. As we know, the Washington Post editorial board is absolutely the most serious of the “very serious people.” They are always worried about the debt and deficit. So, let’s have a little fun with the folks.

First, we can deal with the issue of whether the deficit is too large. There is a pretty simple answer to that. Is there any evidence that it is driving inflation?

If we were back in 2021-2022 when we had serious supply constraints because of the pandemic, the Post would have a pretty good case that the deficit was contributing to inflation. However, it is much harder to make that case now. Inflation has been slowing for the last year and a half and is now almost back to the Fed’s 2.0 percent target. In fact, if we exclude housing, which lags the market, CPI inflation would be just over 1.0 percent for the last year.

High interest rates are playing a role in slowing growth, so we can argue that we could have lower rates with a lower deficit, but we can also have lower rates with the current deficit, as the Fed will tell us tomorrow. It’s also worth noting the current 3.65 percent interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is lower than the rate at any point in the late 1990s when we were running budget surpluses.

In short, perhaps the Fed would give us somewhat lower interest rates if we knocked a few hundred billion off the deficit, but it’s not clear that a 0.1-0.2 percentage point drop in rates would be any big deal from the standpoint of benefitting the economy.

Then we have the issue of the debt. Yes, this is growing, but interestingly, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the long-term picture actually looks slightly better today than it did before the pandemic. The main reason is that CBO now projects healthcare costs will grow at a slower pace than they had projected in 2020.

This is noteworthy for two reasons. There has been a sharp slowing in health care costs since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). As a result, we are spending hundreds of billions a year less, saving more than $3000 per family, than had been projected before the bill was passed.

The other reason this is noteworthy is that we would have close to a balanced budget if our per capita health care costs were comparable to what other wealthy countries pay. While our system has become less wasteful over the last fifteen years, we still spend close to twice as much per person as people in other wealthy countries. There is plenty of waste that can still be wrung out of our healthcare system.

There are two questions to address on the debt. The first is the issue of whether we will face a crisis from the debt-to-GDP ratio getting too high.

The key point on this one is that we have been here before. During the Great Recession, two Harvard economics professors became international celebrities with a paper that purported to show that GDP growth slows sharply when the ratio of the national debt to income exceeds 90 percent. This paper was used as a rationale for austerity in the U.S., the EU, and elsewhere.

It turned out that the main result in the paper was driven by an Excel spreadsheet error. When this was corrected, their 90 percent threshold disappeared.

While others have argued that there is still some crisis threshold, it is not clear why that would be the case. If the United States has a healthy economy, with strong growth and moderate rates of inflation, it is not clear why we would ever face a crisis of investors being unwilling to buy U.S. government debt. Also, as many have noted the Federal Reserve Board can always buy debt if there are few buyers in private markets.

If we were facing a real economic crisis, say plummeting output due to war or climate-related factors, that would be a path towards runaway inflation, but in that case the problem would be the war or the climate-related factors, not the debt. The point here is that our priority should be maintaining a strong economy and then we won’t have to worry about the debt-to-GDP ratio getting too high.

Also, if the economy is growing rapidly, then the debt-to-GDP ratio will be growing less rapidly or even shrinking. That is the story of the drop in the debt to GDP ratio from 116 percent at the end of World War II to less than 40 percent by 1980. The government ran deficits almost every year during this period, but strong growth reduced the ratio of debt-to-GDP.

The other issue with the debt-to-GDP is the interest burden on the debt. We will spend almost $900 billion this year (3.1 percent of GDP) on interest. This is a lot of money that could be better spent on childcare, housing, or in many other areas. But it takes many years of serious austerity before we can make much of a dent in these interest payments.

Furthermore, there is little reason to believe that we are up against hard budget constraints if we want to spend more in these areas now. In other words, if we had the political will to spend another $50 or $100 billion a year on a child tax credit or some other worthwhile program, we could do it even without some offsetting tax increase or budget cut.

Government-Granted Patent and Copyright Monopolies

The other point worth making about the concern over interest payments is that it is very selective. One way the government pays for goods and services is by writing checks. We spend cash and directly add to the deficit and debt. However, the government also pays for a lot of things by granting patent and copyright monopolies. This is the way in which the government pays for innovation in most areas as well as a wide variety of creative work.

The rents from patent and copyright monopolies are huge, almost certainly much larger than the interest we pay each year on the government debt. In the case of prescription drugs alone they likely come to over $500 billion a year. If you add in the additional spending on medical equipment, computers, software and other items we are likely well over $1 trillion annually.

For some reason the Washington Post literally never talks about the burdens created by these government-granted monopolies. The decision to endlessly whine about interest burdens on the debt, but to ignore the much larger amounts paid each year in patent and copyright rents, is a political one. The Post will have to give its own explanation for this call, but it is important for the rest of us to recognize that we routinely ignore these burdens that we are handing down to our children.

Taxing Returns to Shareholders Instead of Profits

It’s also worth noting that if we want to raise more revenue there is an easy route that even the Washington Post editorial board should like, if they are being honest in their professed concerns. While the nominal corporate tax rate is 21 percent, we actually collect much less revenue than this tax rate would imply. This is because corporations have become experts at finding ways to avoid or evade the corporate income tax.

There is a way to circumvent their scheming and wipe out the tax gaming industry. We can switch the basis for the corporate income tax from profits to returns to shareholders (dividends plus capital gains). The advantage of this switch is that the amount that companies pay out in dividends and how much their stock appreciates are factors that are completely transparent. They can be found on dozens of financial websites. By contrast, corporate accountants tell us what corporate profits are.

We can set whatever tax rate Congress considers appropriate, but if it is applied to returns to shareholders, we can be sure that the IRS will actually get it. And by putting the tax gaming industry out of business, we will be freeing up resources (labor and capital) that can instead be used in something productive.

If the Washington Post wants to actually be serious, instead of just giving us the same old deficit hawk schtick, it could promote the idea of taxing stock returns. The tax on share buybacks was a useful first step. But don’t hold your breath.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Readers are undoubtedly confused by the reference to 1000 percent tariffs on prescription drugs. We don’t call our protection for prescription drug companies “tariffs,” we call them “patent monopolies.” But government interventions in the market don’t care what we call them, they have the same effect.

Like tariffs on imports, government-granted patent monopolies hugely raise the cost of prescription drugs, often making the price ten or even a hundred times as much as the free market price. In a free market without patents or related protections, drugs would almost invariably be cheap. It’s rare that it would cost more than $20 or $30 per prescription to manufacture and distribute drugs, and often considerably less. Patent monopolies allow drug companies sell drugs for hundreds or even thousands of dollars per prescription.

This would be a bad story if we were talking about smartphones or running shoes, but it is an especially bad story when we are talking about drugs that people need for their health or even their life. As it is now, because of patent monopolies people often have to struggle to get the money they need for life-saving drugs or battle with insurers to cover the costs. This would not be the case if drugs were selling for their free market prices.

In addition to hugely raising the price of prescription drugs, patent monopolies also provide enormous incentives for drug companies to mislead the public about the safety and effectiveness of their drugs. We saw this most clearly in the opioid crisis, where the drug companies misled the public about the addictiveness of the new generation of opioids, but this is a recurring problem. Economics teaches us that people respond to incentives and patent monopoly prices provide an enormous incentive to push drugs as widely as possible even if it means exaggerating their benefits and downplaying their risks.