As the world awaits the final word on the negotiations between Greece and its creditors, it’s worth a quick flashback to 2010 and the report of Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles, the co-chairs of President Obama’s deficit commission. (This report is often referred to as a report of the commission. That is not true. The by-laws clearly state that to issue a report it was necessary to have the support of 12 of the 16 commission members. While no formal vote was ever taken, the co-chairs’ report only had the support of 10 members.)

Anyhow, getting back to matters at hand, one of the Simpson-Bowles proposals was to raise the normal retirement age for Social Security to 69 from its current level of 66 (soon to be 67). The report recognized that many people work in physically demanding and/or dangerous jobs where it would be unreasonable to expect people to work this late in life. It therefore proposed having special lower retirement ages for certain occupations.

The reason this is relevant to Greece is that one of the sticking points at the moment is the reform of Greece’s public pension system. One of the main issues is that the current system allows people in many occupations to start collecting benefits well before the normal retirement age. For example, hairdressers are apparently among this group because they are exposed to dangerous chemicals on the job.

While the Greek system was a universal target of ridicule among serious minded people everywhere, many of these same people embraced the Simpson-Bowles report as a gem of thoughtful, non-partisan, policy-making. The ability to ignore the fact that the supposedly thoughtful Bowles-Simpson gang were advocating the adoption of a pension system subject to universal ridicule is yet another example of the lack of seriousness of the serious people.

As the world awaits the final word on the negotiations between Greece and its creditors, it’s worth a quick flashback to 2010 and the report of Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles, the co-chairs of President Obama’s deficit commission. (This report is often referred to as a report of the commission. That is not true. The by-laws clearly state that to issue a report it was necessary to have the support of 12 of the 16 commission members. While no formal vote was ever taken, the co-chairs’ report only had the support of 10 members.)

Anyhow, getting back to matters at hand, one of the Simpson-Bowles proposals was to raise the normal retirement age for Social Security to 69 from its current level of 66 (soon to be 67). The report recognized that many people work in physically demanding and/or dangerous jobs where it would be unreasonable to expect people to work this late in life. It therefore proposed having special lower retirement ages for certain occupations.

The reason this is relevant to Greece is that one of the sticking points at the moment is the reform of Greece’s public pension system. One of the main issues is that the current system allows people in many occupations to start collecting benefits well before the normal retirement age. For example, hairdressers are apparently among this group because they are exposed to dangerous chemicals on the job.

While the Greek system was a universal target of ridicule among serious minded people everywhere, many of these same people embraced the Simpson-Bowles report as a gem of thoughtful, non-partisan, policy-making. The ability to ignore the fact that the supposedly thoughtful Bowles-Simpson gang were advocating the adoption of a pension system subject to universal ridicule is yet another example of the lack of seriousness of the serious people.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Economists may not be very good at understanding the economy, but they are quite good at finding ways to keep themselves employed, generally at very high wages. The Washington Post treated us to one such make work project as it reported on a change in consumer psychology due to the recession that has left:

“Americans of all ages less willing to inject their money back into the economy in the form of vacations, clothing and nights out.

“It’s a sharp contrast to the 1990s, when consumers spent freely as their wages rose robustly, and the 2000s, when Americans funded more lavish lifestyles with easy access to credit cards and home-equity loans.”

Really? That sounds like a startling development. Let’s see if we can find it in the data.

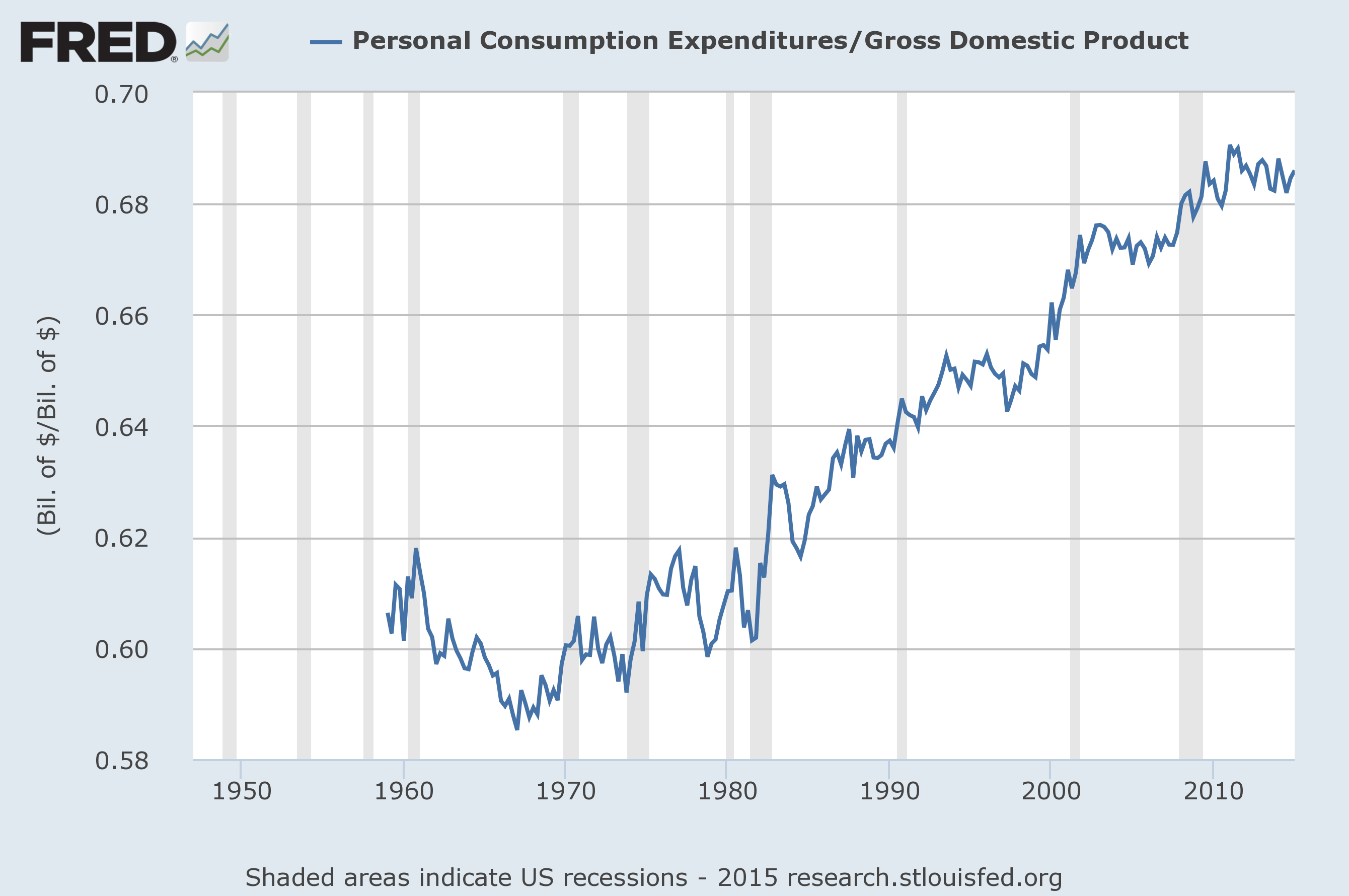

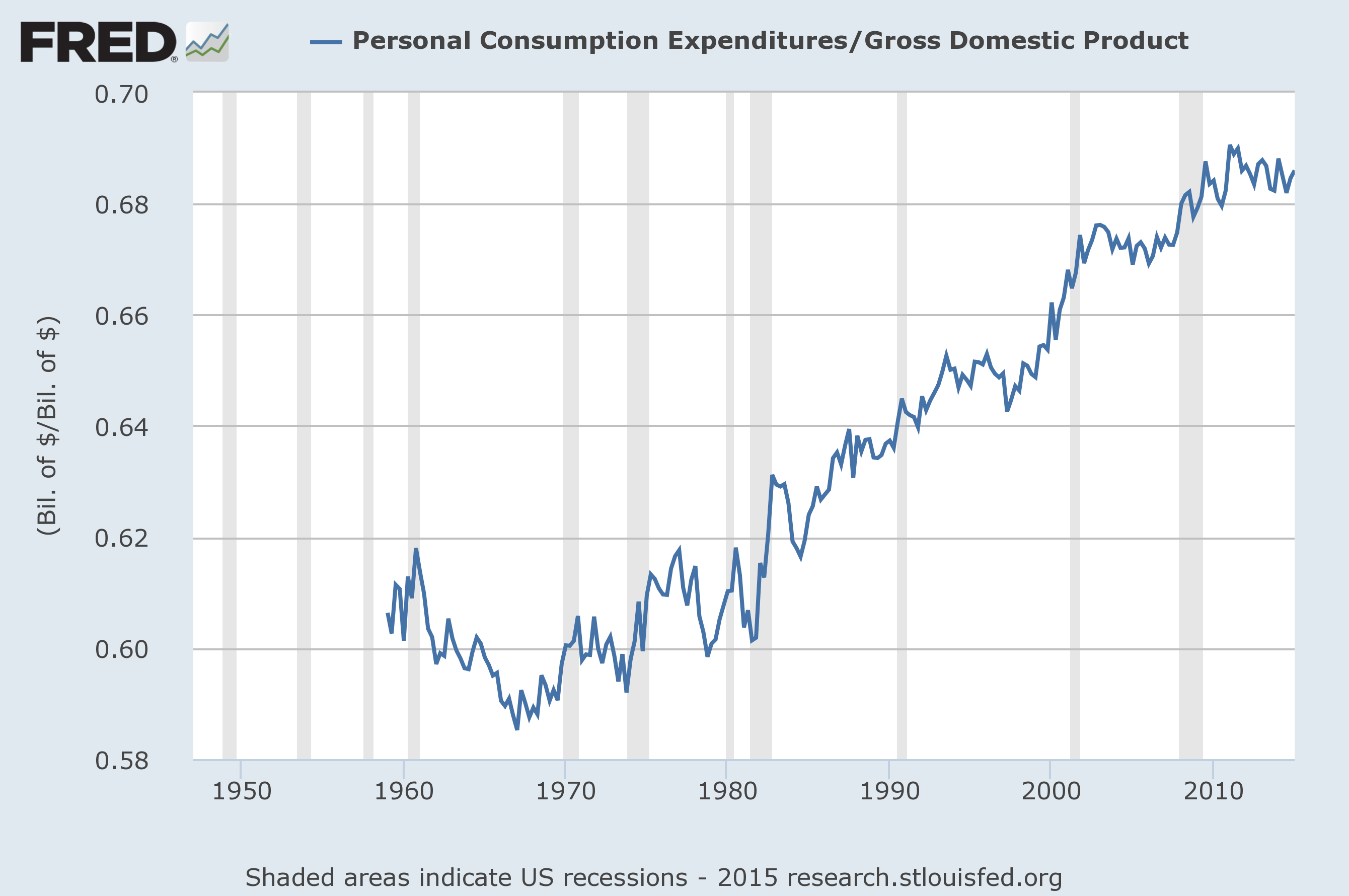

The chart shows consumption as a percentage of GDP. I went back to the late fifties so folks can see the longer term picture. People are spending far more today relative to the size of the economy than they did in the sixties, seventies, eighties, or even nineties. In fact, consumer expenditures are higher now relative to the size of economy than they were in the housing bubble days.

So, let’s ask about that psychology story. Apparently the concern is that we fell from a ratio of 68.8 percent in the first quarter of last year all the way down to 68.6 percent in the most recent quarter. My guess is that modest decline is best explained by unusually bad weather in the first quarter that discouraged people from shopping and going out for meals. Also, extraordinarily strong car sales in the second half of 2014 probably let to some falloff in the first quarter since people who buy a new car in the fall generally don’t buy another one in the winter.

But hey, I don’t want to see a lot of unemployed economists. There should be lots of work in looking for a plunge in consumption that isn’t there.

Economists may not be very good at understanding the economy, but they are quite good at finding ways to keep themselves employed, generally at very high wages. The Washington Post treated us to one such make work project as it reported on a change in consumer psychology due to the recession that has left:

“Americans of all ages less willing to inject their money back into the economy in the form of vacations, clothing and nights out.

“It’s a sharp contrast to the 1990s, when consumers spent freely as their wages rose robustly, and the 2000s, when Americans funded more lavish lifestyles with easy access to credit cards and home-equity loans.”

Really? That sounds like a startling development. Let’s see if we can find it in the data.

The chart shows consumption as a percentage of GDP. I went back to the late fifties so folks can see the longer term picture. People are spending far more today relative to the size of the economy than they did in the sixties, seventies, eighties, or even nineties. In fact, consumer expenditures are higher now relative to the size of economy than they were in the housing bubble days.

So, let’s ask about that psychology story. Apparently the concern is that we fell from a ratio of 68.8 percent in the first quarter of last year all the way down to 68.6 percent in the most recent quarter. My guess is that modest decline is best explained by unusually bad weather in the first quarter that discouraged people from shopping and going out for meals. Also, extraordinarily strong car sales in the second half of 2014 probably let to some falloff in the first quarter since people who buy a new car in the fall generally don’t buy another one in the winter.

But hey, I don’t want to see a lot of unemployed economists. There should be lots of work in looking for a plunge in consumption that isn’t there.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Today’s culprit is National Public Radio. The point here is extremely simple. We know how fast robots and other technologies are replacing workers. In fact the Bureau of Labor Statistics measures it quarterly, it’s called “productivity growth.”

Productivity growth has actually been very slow in the last decade, as in the opposite of robots stealing our jobs. But hey, why should news outlets be limited by data?

By contrast, if the Fed starts raising interest rates, it can prevent millions of people from getting jobs over the next few years. This will also keep tens of millions from getting pay raises since a weak labor market will reduce their bargaining power. But hey, why bother listeners and readers with this stuff, let’s have another piece on those nifty robots.

Today’s culprit is National Public Radio. The point here is extremely simple. We know how fast robots and other technologies are replacing workers. In fact the Bureau of Labor Statistics measures it quarterly, it’s called “productivity growth.”

Productivity growth has actually been very slow in the last decade, as in the opposite of robots stealing our jobs. But hey, why should news outlets be limited by data?

By contrast, if the Fed starts raising interest rates, it can prevent millions of people from getting jobs over the next few years. This will also keep tens of millions from getting pay raises since a weak labor market will reduce their bargaining power. But hey, why bother listeners and readers with this stuff, let’s have another piece on those nifty robots.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Morning Edition had a segment on computer tablets that many restaurants are now placing on dining tables which allow people to order and pay their bill without needing a waiter or waitress. The point of the piece is that these tablets are likely to cost the jobs of many table servers.

While this is true, we have always seen productivity growth. (That is what it means to displace workers with robots or computers.) Contrary to what you might believe from reports like this on NPR, productivity growth has actually been very slow in the last decade, as in the opposite of robots taking our jobs. Here’s the data on productivity in the restaurant industry over the last three decades.

Productivity in the Restaurant Industry: 1987-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen, productivity increased relatively rapidly in the restaurant industry from 1996 to 2006. Since 2006 productivity has actually fallen in the industry. That means that restaurants are getting less money for each hour of their employees’ work. It might be interesting to hear a segment on why we seem to have such low productivity (i.e. negative) growth in sectors like restaurants rather than implying that we are seeing the opposite story.

Morning Edition had a segment on computer tablets that many restaurants are now placing on dining tables which allow people to order and pay their bill without needing a waiter or waitress. The point of the piece is that these tablets are likely to cost the jobs of many table servers.

While this is true, we have always seen productivity growth. (That is what it means to displace workers with robots or computers.) Contrary to what you might believe from reports like this on NPR, productivity growth has actually been very slow in the last decade, as in the opposite of robots taking our jobs. Here’s the data on productivity in the restaurant industry over the last three decades.

Productivity in the Restaurant Industry: 1987-2013

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

As can be seen, productivity increased relatively rapidly in the restaurant industry from 1996 to 2006. Since 2006 productivity has actually fallen in the industry. That means that restaurants are getting less money for each hour of their employees’ work. It might be interesting to hear a segment on why we seem to have such low productivity (i.e. negative) growth in sectors like restaurants rather than implying that we are seeing the opposite story.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

John Delaney, a Democratic congressperson from Maryland, argued against a “left-wing” Tea Party in a Washington Post column today. He gets many things badly wrong, like arguing:

“bipartisan tax reform that would free up the trillions of dollars of trapped overseas cash” which he says could be used for infrastructure spending. Sorry, corporations do have trillions in profits that they record as being overseas to avoid taxes, but the idea that we have some formula that would turn all this money into tax revenue for infrastructure is more than a bit loopy. He also seems to think that a modest expansion of Social Security, as proposed by people like Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, would impose some impossible tax burden.

But my favorite part is when he denounces the opponents of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) as protectionists. I must confess to not knowing exactly what is in the agreement (it is secret), but we do know from Wikileaks that an important part of the TPP is increasing protectionism in the form of stronger and longer copyright and patent protection.

Since we already have trade agreements with most of the countries in the TPP, there will not be very much by way of tariff reduction in the TPP. In other words, the trade liberalization parts of the TPP will be relatively minor. Given this fact, it is entirely possible that the increase in copyright and patent protections will have more economic impact than the modest reductions in the remaining tariff barriers. (Remember patent protection can increase the price of a drug by a hundredfold, the equivalent of a 10,000 percent tariff barrier.)

Until it is shown otherwise, it is reasonable to call the TPP a protectionist pact. We know that it will increase protectionism in important areas. We don’t know how much it will liberalize trade and therefore have zero basis for assuming that on net it moves in the direction of freer trade.

So Mr. Delaney, if it’s name-calling time, right back at you. As a TPP supporter, you are a protectionist.

John Delaney, a Democratic congressperson from Maryland, argued against a “left-wing” Tea Party in a Washington Post column today. He gets many things badly wrong, like arguing:

“bipartisan tax reform that would free up the trillions of dollars of trapped overseas cash” which he says could be used for infrastructure spending. Sorry, corporations do have trillions in profits that they record as being overseas to avoid taxes, but the idea that we have some formula that would turn all this money into tax revenue for infrastructure is more than a bit loopy. He also seems to think that a modest expansion of Social Security, as proposed by people like Senators Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders, would impose some impossible tax burden.

But my favorite part is when he denounces the opponents of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) as protectionists. I must confess to not knowing exactly what is in the agreement (it is secret), but we do know from Wikileaks that an important part of the TPP is increasing protectionism in the form of stronger and longer copyright and patent protection.

Since we already have trade agreements with most of the countries in the TPP, there will not be very much by way of tariff reduction in the TPP. In other words, the trade liberalization parts of the TPP will be relatively minor. Given this fact, it is entirely possible that the increase in copyright and patent protections will have more economic impact than the modest reductions in the remaining tariff barriers. (Remember patent protection can increase the price of a drug by a hundredfold, the equivalent of a 10,000 percent tariff barrier.)

Until it is shown otherwise, it is reasonable to call the TPP a protectionist pact. We know that it will increase protectionism in important areas. We don’t know how much it will liberalize trade and therefore have zero basis for assuming that on net it moves in the direction of freer trade.

So Mr. Delaney, if it’s name-calling time, right back at you. As a TPP supporter, you are a protectionist.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Many folks are dismissing the negative GDP number from the first quarter by arguing that the Commerce Department’s seasonal adjustment is faulty. According to some estimates a correct seasonal adjustment could add as much as 0.8 percentage points, which would be enough to bring the first quarter GDP into positive territory.

However seasonal adjustments must sum to one over the course of the year. In other words, if weather and other regular seasonal factors are more of a drag on first quarter growth than the Commerce Department acknowledges in its current seasonal adjustment, then the Commerce Department must be understating the extent to which weather and other seasonal factors provide a boost to growth in other quarters. The cost of saying that the first quarters (this and prior years) is better than the data show is that it means the data for other quarters are worse than the current methodology indicate. In other words, this will not qualitatively change our assessment of how fast the economy is growing, even if it may shift the timing between quarters.

Many folks are dismissing the negative GDP number from the first quarter by arguing that the Commerce Department’s seasonal adjustment is faulty. According to some estimates a correct seasonal adjustment could add as much as 0.8 percentage points, which would be enough to bring the first quarter GDP into positive territory.

However seasonal adjustments must sum to one over the course of the year. In other words, if weather and other regular seasonal factors are more of a drag on first quarter growth than the Commerce Department acknowledges in its current seasonal adjustment, then the Commerce Department must be understating the extent to which weather and other seasonal factors provide a boost to growth in other quarters. The cost of saying that the first quarters (this and prior years) is better than the data show is that it means the data for other quarters are worse than the current methodology indicate. In other words, this will not qualitatively change our assessment of how fast the economy is growing, even if it may shift the timing between quarters.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Last week I noted the gift from the gods that the re-authorization of the Export-Import Bank is coming up at the same time as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The great fun here is that the TPP proponents are running around being sanctimonious supporters of free trade. However the main purpose of the Export-Import Bank is to subsidize U.S. exports (mostly those of large corporations). Subsidizing exports is 180 degrees at odds with free trade, it’s sort of like having sex to promote virginity, but naturally many of our great leaders in Washington support both.

We got another treat this week along the same lines in a Politico piece by Michael Grunwald arguing against breaking up the too big to fail (TBTF) banks. There is much in the piece that is wrong (e.g. he asserts that the biggest banks were not at the center of the financial crisis) but the key section for these purposes is when he tells readers:

“There’s much to dislike about America’s financial sector, but it is America’s financial sector. It’s actually much smaller as a percentage of the economy than its counterparts in Asia and Europe, and it’s much less concentrated at the top . Unilaterally enforcing size limits on domestic banks would put the U.S. at a real competitive disadvantage in financial services.”

Almost all of Grunwald’s argument is completely wrong (breaking up J.P. Morgan doesn’t reduce its components and competitors to “community banks”). But the key point is that this is yet another example of an Obama-type (he collaborated in writing Timothy Geithner’s autobiography) arguing for a government subsidy to help a favored interest group. Allowing the implicit guarantee of TBTF insurance is a massive government subsidy that the I.M.F. recently estimated to have a value of up to $70 billion a year for the United States. So once again we have a free trader arguing for government subsidies when something really important to them is at stake, in this case the survival of the Wall Street banks.

Given all the money and power on the side of the proponents of TPP, they are likely to get their deal through Congress. At least the rest of us can enjoy the spectacle of all these elite types making incredibly silly arguments.

Last week I noted the gift from the gods that the re-authorization of the Export-Import Bank is coming up at the same time as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The great fun here is that the TPP proponents are running around being sanctimonious supporters of free trade. However the main purpose of the Export-Import Bank is to subsidize U.S. exports (mostly those of large corporations). Subsidizing exports is 180 degrees at odds with free trade, it’s sort of like having sex to promote virginity, but naturally many of our great leaders in Washington support both.

We got another treat this week along the same lines in a Politico piece by Michael Grunwald arguing against breaking up the too big to fail (TBTF) banks. There is much in the piece that is wrong (e.g. he asserts that the biggest banks were not at the center of the financial crisis) but the key section for these purposes is when he tells readers:

“There’s much to dislike about America’s financial sector, but it is America’s financial sector. It’s actually much smaller as a percentage of the economy than its counterparts in Asia and Europe, and it’s much less concentrated at the top . Unilaterally enforcing size limits on domestic banks would put the U.S. at a real competitive disadvantage in financial services.”

Almost all of Grunwald’s argument is completely wrong (breaking up J.P. Morgan doesn’t reduce its components and competitors to “community banks”). But the key point is that this is yet another example of an Obama-type (he collaborated in writing Timothy Geithner’s autobiography) arguing for a government subsidy to help a favored interest group. Allowing the implicit guarantee of TBTF insurance is a massive government subsidy that the I.M.F. recently estimated to have a value of up to $70 billion a year for the United States. So once again we have a free trader arguing for government subsidies when something really important to them is at stake, in this case the survival of the Wall Street banks.

Given all the money and power on the side of the proponents of TPP, they are likely to get their deal through Congress. At least the rest of us can enjoy the spectacle of all these elite types making incredibly silly arguments.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Billionaire Peter Peterson is spending lots of money to get people to worry about the debt and deficits rather than focus on the issues that will affect their lives. National Public Radio is doing its part to try to promote Peterson’s cause with a Morning Edition piece that began by telling people that the next president “will have to wrestle with the federal debt.” This is not true, but it is the hope of Peter Peterson that he can distract the public from the factors that will affect their lives, most importantly the upward redistribution of income, and obsess on the country’s relative small deficit. (A larger deficit right now would promote growth and employment.)

According to the projections from the Congressional Budget Office, interest on the debt will be well below 2.0 percent of GDP when the next president takes office. This is lower than the interest burden faced by any pre-Obama president since Jimmy Carter. The interest burden is projected to rise to 3.0 percent of GDP by 2024 when the next president’s second term is ending, but this would still be below the burden faced by President Clinton when he took office.

Furthermore, the reason for the projected rise in the burden is a projection that the Federal Reserve Board is projected to raise interest rates. If the Fed kept interest rates low, then the burden would be little changed over the course of the decade. Of course the Fed’s decision to raise interest rates will have a far greater direct impact on people’s lives than increasing interest costs for the government. (The president appoints 7 of the 12 voting members of the Fed’s Open Market Committee that sets interest rates.)

The reason the Fed raises interest rates is to slow the economy and keep people from getting jobs. This will prevent the labor market from tightening, which will prevent workers from having enough bargaining power to get pay increases. In that case, the bulk of the gains from economic growth will continue to go to those at the top end of the income distribution.

The main reason that we saw strong wage growth at the end of the 1990s was that Alan Greenspan ignored the accepted wisdom in the economics profession, including among the liberal economists appointed to the Fed by President Clinton, and allowed the unemployment rate to drop well below 6.0 percent. At the time, almost all economists believed that if the unemployment rate fell much below 6.0 percent that inflation would spiral out of control. The economists were wrong, inflation was little changed even though the unemployment rate remained below 6.0 from the middle of 1995 until 2001, and averaged just 4.0 percent for all of 2000. (Economists, unlike custodians and dishwashers, suffer no consequence in their careers for messing up on the job.)

Anyhow, if the Fed raises interest rates to keep the labor market from tightening as it did in the late 1990s, this would effectively be depriving workers of the 1.0-1.5 percentage points in real wage growth they could expect if they were getting their share of productivity growth. This is like an increase in the payroll tax of 1.0-1.5 percentage points annually. Over the course of a two-term president, this would be the equivalent of an 8.0-12.0 percentage point increase in the payroll tax.

That would be a really big deal. But Peter Peterson and apparently NPR would rather have the public worry about the budget deficit.

It is also worth noting that the five think tanks mentioned in this piece that prepared deficit plans were paid by the Peter Peterson Foundation to prepare defict plans. They did not do it because they considered it the best use of their time.

Billionaire Peter Peterson is spending lots of money to get people to worry about the debt and deficits rather than focus on the issues that will affect their lives. National Public Radio is doing its part to try to promote Peterson’s cause with a Morning Edition piece that began by telling people that the next president “will have to wrestle with the federal debt.” This is not true, but it is the hope of Peter Peterson that he can distract the public from the factors that will affect their lives, most importantly the upward redistribution of income, and obsess on the country’s relative small deficit. (A larger deficit right now would promote growth and employment.)

According to the projections from the Congressional Budget Office, interest on the debt will be well below 2.0 percent of GDP when the next president takes office. This is lower than the interest burden faced by any pre-Obama president since Jimmy Carter. The interest burden is projected to rise to 3.0 percent of GDP by 2024 when the next president’s second term is ending, but this would still be below the burden faced by President Clinton when he took office.

Furthermore, the reason for the projected rise in the burden is a projection that the Federal Reserve Board is projected to raise interest rates. If the Fed kept interest rates low, then the burden would be little changed over the course of the decade. Of course the Fed’s decision to raise interest rates will have a far greater direct impact on people’s lives than increasing interest costs for the government. (The president appoints 7 of the 12 voting members of the Fed’s Open Market Committee that sets interest rates.)

The reason the Fed raises interest rates is to slow the economy and keep people from getting jobs. This will prevent the labor market from tightening, which will prevent workers from having enough bargaining power to get pay increases. In that case, the bulk of the gains from economic growth will continue to go to those at the top end of the income distribution.

The main reason that we saw strong wage growth at the end of the 1990s was that Alan Greenspan ignored the accepted wisdom in the economics profession, including among the liberal economists appointed to the Fed by President Clinton, and allowed the unemployment rate to drop well below 6.0 percent. At the time, almost all economists believed that if the unemployment rate fell much below 6.0 percent that inflation would spiral out of control. The economists were wrong, inflation was little changed even though the unemployment rate remained below 6.0 from the middle of 1995 until 2001, and averaged just 4.0 percent for all of 2000. (Economists, unlike custodians and dishwashers, suffer no consequence in their careers for messing up on the job.)

Anyhow, if the Fed raises interest rates to keep the labor market from tightening as it did in the late 1990s, this would effectively be depriving workers of the 1.0-1.5 percentage points in real wage growth they could expect if they were getting their share of productivity growth. This is like an increase in the payroll tax of 1.0-1.5 percentage points annually. Over the course of a two-term president, this would be the equivalent of an 8.0-12.0 percentage point increase in the payroll tax.

That would be a really big deal. But Peter Peterson and apparently NPR would rather have the public worry about the budget deficit.

It is also worth noting that the five think tanks mentioned in this piece that prepared deficit plans were paid by the Peter Peterson Foundation to prepare defict plans. They did not do it because they considered it the best use of their time.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

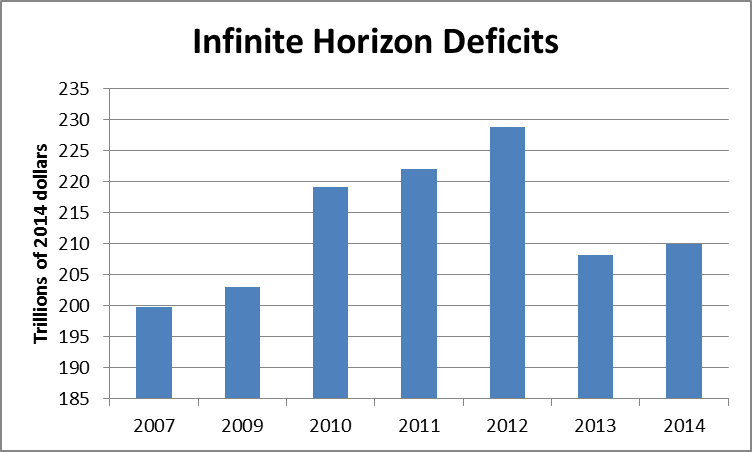

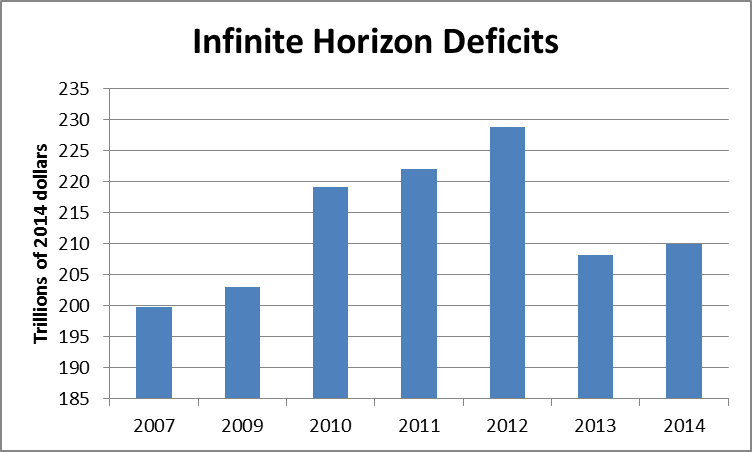

Given the obsession with the government budget deficit that NPR shares with most major news outlets, you would think they would find some room to mention a drop in the defcit of $20 trillion (yes, that’s “trillion” with a “t”), but no, apparently they didn’t think it was important.

If this sounds very strange to you, it’s because the decline is in a bizarre measure of the deficit known as the “infinite horizon” budget deficit. Its originator was Boston University professor Lawrence Kotlikoff. The idea is to make projections of spending for the infinite future, compare them to projections of revenue, and then calculate the shortfall.

This can lead to some very large figures. For example, when NPR chose to report on the number back in 2011, the figure was $211 trillion (measured in 2011 dollars). I criticized the network at the time because this number was mentioned with absolutely zero context. Not only is there the problem that we are making projections for decades and centuries into the future (hey, will 2108 be a good year?), there is also the problem that almost no one hearing this number would have any idea what it means.

NPR has a well-educated listenership, but I would be quite certain that less than one in a thousand of their listeners would be able to tell much difference if the number was cut in half or doubled. $211 trillion is a really big number, but so is $106 trillion or $422 trillion. If the point is to convey information rather than just scare people then the number could at least have been expressed as share of future income. (It would have been just under 13 percent.)

It also would have been helpful to note that the main factor driving this large deficit was a projected explosion in health care costs. Under the assumptions used in the deficit calculations, the average health care costs for an 85-year old would be over $45,000 a year in 2030 and over $110,000 a year in 2080 (both numbers are in 2015 dollars). If these numbers prove accurate, we would face an enormous problem regardless of what we did with Medicare and Medicaid. Almost no seniors would be able to afford health care (nor would most other people). By just reporting the deficit numbers, NPR was implying that the problem was one of public spending as opposed to a broken health care system. (No other wealthy country is projected to experience a similar explosion of health care costs, which suggests the obvious solution of having people use more efficient health care systems elsewhere, but public debate is controlled by ardent protectionists.)

But there is a further point worth making about whether NPR’s intentions were to scare or inform their listeners. By Kotlikoff’s own calculations the deficit fell by more than $20 trillion between 2012 and 2013, a decline of just under 9 percent.

Source: Kotlikoff, 2015. Numbers adjusted for inflation using CPI-U.

If it was important for the public to know that the deficit by Kotlikoff’s measure was over $200 trillion back in 2011, presumably it would also have been important for the public to know that Kotlikoff’s infinite horizon deficit had fallen by $20 trillion two years later. Why no coverage?

Given the obsession with the government budget deficit that NPR shares with most major news outlets, you would think they would find some room to mention a drop in the defcit of $20 trillion (yes, that’s “trillion” with a “t”), but no, apparently they didn’t think it was important.

If this sounds very strange to you, it’s because the decline is in a bizarre measure of the deficit known as the “infinite horizon” budget deficit. Its originator was Boston University professor Lawrence Kotlikoff. The idea is to make projections of spending for the infinite future, compare them to projections of revenue, and then calculate the shortfall.

This can lead to some very large figures. For example, when NPR chose to report on the number back in 2011, the figure was $211 trillion (measured in 2011 dollars). I criticized the network at the time because this number was mentioned with absolutely zero context. Not only is there the problem that we are making projections for decades and centuries into the future (hey, will 2108 be a good year?), there is also the problem that almost no one hearing this number would have any idea what it means.

NPR has a well-educated listenership, but I would be quite certain that less than one in a thousand of their listeners would be able to tell much difference if the number was cut in half or doubled. $211 trillion is a really big number, but so is $106 trillion or $422 trillion. If the point is to convey information rather than just scare people then the number could at least have been expressed as share of future income. (It would have been just under 13 percent.)

It also would have been helpful to note that the main factor driving this large deficit was a projected explosion in health care costs. Under the assumptions used in the deficit calculations, the average health care costs for an 85-year old would be over $45,000 a year in 2030 and over $110,000 a year in 2080 (both numbers are in 2015 dollars). If these numbers prove accurate, we would face an enormous problem regardless of what we did with Medicare and Medicaid. Almost no seniors would be able to afford health care (nor would most other people). By just reporting the deficit numbers, NPR was implying that the problem was one of public spending as opposed to a broken health care system. (No other wealthy country is projected to experience a similar explosion of health care costs, which suggests the obvious solution of having people use more efficient health care systems elsewhere, but public debate is controlled by ardent protectionists.)

But there is a further point worth making about whether NPR’s intentions were to scare or inform their listeners. By Kotlikoff’s own calculations the deficit fell by more than $20 trillion between 2012 and 2013, a decline of just under 9 percent.

Source: Kotlikoff, 2015. Numbers adjusted for inflation using CPI-U.

If it was important for the public to know that the deficit by Kotlikoff’s measure was over $200 trillion back in 2011, presumably it would also have been important for the public to know that Kotlikoff’s infinite horizon deficit had fallen by $20 trillion two years later. Why no coverage?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión