Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT apparently thinks this is a common practice. An article discussing a Supreme Court ruling that a second mortgage could not be discharged in a chapter 7 bankruptcy filing even when the homeowner’s first mortgage vastly exceeded the value of the house, told readers:

“a ruling in favor of the homeowners might have made banks and other lenders less willing to extend second mortgages in the future.”

In a foreclosure, a first mortgage must be paid in full before a dollar can be paid on a second mortgage. In the case before the court, the first mortgage was for $183,000, while the home was valued at $98,000. The homeowner therefore argued that the second mortgage was effectively unsecured debt that should be discharged in bankruptcy.

A ruling in favor of the homeowner would only affect banks’ lending behavior if they think there is a substantial probability that a home will fall below the value of a first mortgage. If they do believe this risk to be large enough to affect their lending, then it is probably best for the homeowner and the economy more generally that the second mortgage not be issued.

The NYT apparently thinks this is a common practice. An article discussing a Supreme Court ruling that a second mortgage could not be discharged in a chapter 7 bankruptcy filing even when the homeowner’s first mortgage vastly exceeded the value of the house, told readers:

“a ruling in favor of the homeowners might have made banks and other lenders less willing to extend second mortgages in the future.”

In a foreclosure, a first mortgage must be paid in full before a dollar can be paid on a second mortgage. In the case before the court, the first mortgage was for $183,000, while the home was valued at $98,000. The homeowner therefore argued that the second mortgage was effectively unsecured debt that should be discharged in bankruptcy.

A ruling in favor of the homeowner would only affect banks’ lending behavior if they think there is a substantial probability that a home will fall below the value of a first mortgage. If they do believe this risk to be large enough to affect their lending, then it is probably best for the homeowner and the economy more generally that the second mortgage not be issued.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is amazing how economic reporters continue to repeat nonsense about deflation. As fans of arithmetic and logic everywhere know, deflation is bad for the same reason a lower rate of inflation is bad. It raises the real interest rate at a time when we want a lower real interest rate and it increases the real value of debt when we want to see the real value of debt reduced. (The real interest rate is the nominal interest minus the inflation rate.)

Crossing zero means nothing, which should be obvious to anyone who has given the issue a moment’s thought. The inflation rate is a sum of millions of different price changes. When it is near zero, many prices are already falling. When it crosses zero and becomes negative, that means a somewhat larger share of prices are falling. So what? Since prices are quality adjusted, the prices people pay may still be rising.

Anyhow, the NYT added to the silliness yet again when it told readers that price declines in the euro zone due to falling energy prices are a potential problem. Let’s think this one through for a moment. Suppose that prices are rising at a 1.0 percent annual rate. Given the weakness of the euro zone economy that is lower than would be desirable, but let’s use that as a starting point.

Now let’s have energy prices fall at a 40 percent annual rate so that prices are now falling at a 1.0 percent annual rate. Let’s assume that the rate of inflation for non-energy prices has not changed.

Now how does this make things worse? People used to be pay more for gas and heat, with most of that money ending up outside of the euro zone. With the lower prices, this money stays in their pocket for them to spend on other things. In terms of debt burdens, if wages are rising in step with inflation, then the real value of debt to workers is being eroded at exactly the same rate as before. And since non-energy prices are still rising at the same pace, the real interest rate for investment outside the energy sector has not changed.

So what is the problem? It would be great if the NYT could get someone other than deflation cultists to do their economic reporting.

It is amazing how economic reporters continue to repeat nonsense about deflation. As fans of arithmetic and logic everywhere know, deflation is bad for the same reason a lower rate of inflation is bad. It raises the real interest rate at a time when we want a lower real interest rate and it increases the real value of debt when we want to see the real value of debt reduced. (The real interest rate is the nominal interest minus the inflation rate.)

Crossing zero means nothing, which should be obvious to anyone who has given the issue a moment’s thought. The inflation rate is a sum of millions of different price changes. When it is near zero, many prices are already falling. When it crosses zero and becomes negative, that means a somewhat larger share of prices are falling. So what? Since prices are quality adjusted, the prices people pay may still be rising.

Anyhow, the NYT added to the silliness yet again when it told readers that price declines in the euro zone due to falling energy prices are a potential problem. Let’s think this one through for a moment. Suppose that prices are rising at a 1.0 percent annual rate. Given the weakness of the euro zone economy that is lower than would be desirable, but let’s use that as a starting point.

Now let’s have energy prices fall at a 40 percent annual rate so that prices are now falling at a 1.0 percent annual rate. Let’s assume that the rate of inflation for non-energy prices has not changed.

Now how does this make things worse? People used to be pay more for gas and heat, with most of that money ending up outside of the euro zone. With the lower prices, this money stays in their pocket for them to spend on other things. In terms of debt burdens, if wages are rising in step with inflation, then the real value of debt to workers is being eroded at exactly the same rate as before. And since non-energy prices are still rising at the same pace, the real interest rate for investment outside the energy sector has not changed.

So what is the problem? It would be great if the NYT could get someone other than deflation cultists to do their economic reporting.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Undoubtedly millions of readers are wondering about the NYT’s use of the term when it told readers that one of the goals of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is to, “protect intellectual property from theft.” Actually one of the goals of the TPP is to strengthen and lengthen patent and copyright protections.

After this is done, those who do not respect the new laws can be accused of “theft,” however it makes no sense to accuse someone of theft for breaking laws that do not exist. The NYT may want strong and long protections, but a newspaper should not be calling people who do not adhere to its views of intellectual property “thieves.”

Undoubtedly millions of readers are wondering about the NYT’s use of the term when it told readers that one of the goals of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is to, “protect intellectual property from theft.” Actually one of the goals of the TPP is to strengthen and lengthen patent and copyright protections.

After this is done, those who do not respect the new laws can be accused of “theft,” however it makes no sense to accuse someone of theft for breaking laws that do not exist. The NYT may want strong and long protections, but a newspaper should not be calling people who do not adhere to its views of intellectual property “thieves.”

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Robert Samuelson used his Monday column to tell readers that the problem with the economy is that we are suffering the psychological fallout of the Great Recession:

“My main explanation for this — as I’ve argued before — is the hangover from the 2008-2009 financial crisis and the Great Recession. These events changed economic psychology, precisely because they were unanticipated and horrific. They transcended the experience of most Americans (that is, anyone who hadn’t lived through the Great Depression). Corporate executives and consumers alike became more defensive; they saved and hoarded a bit more. If a novel calamity struck once, it could strike again. They’d better prepare.”

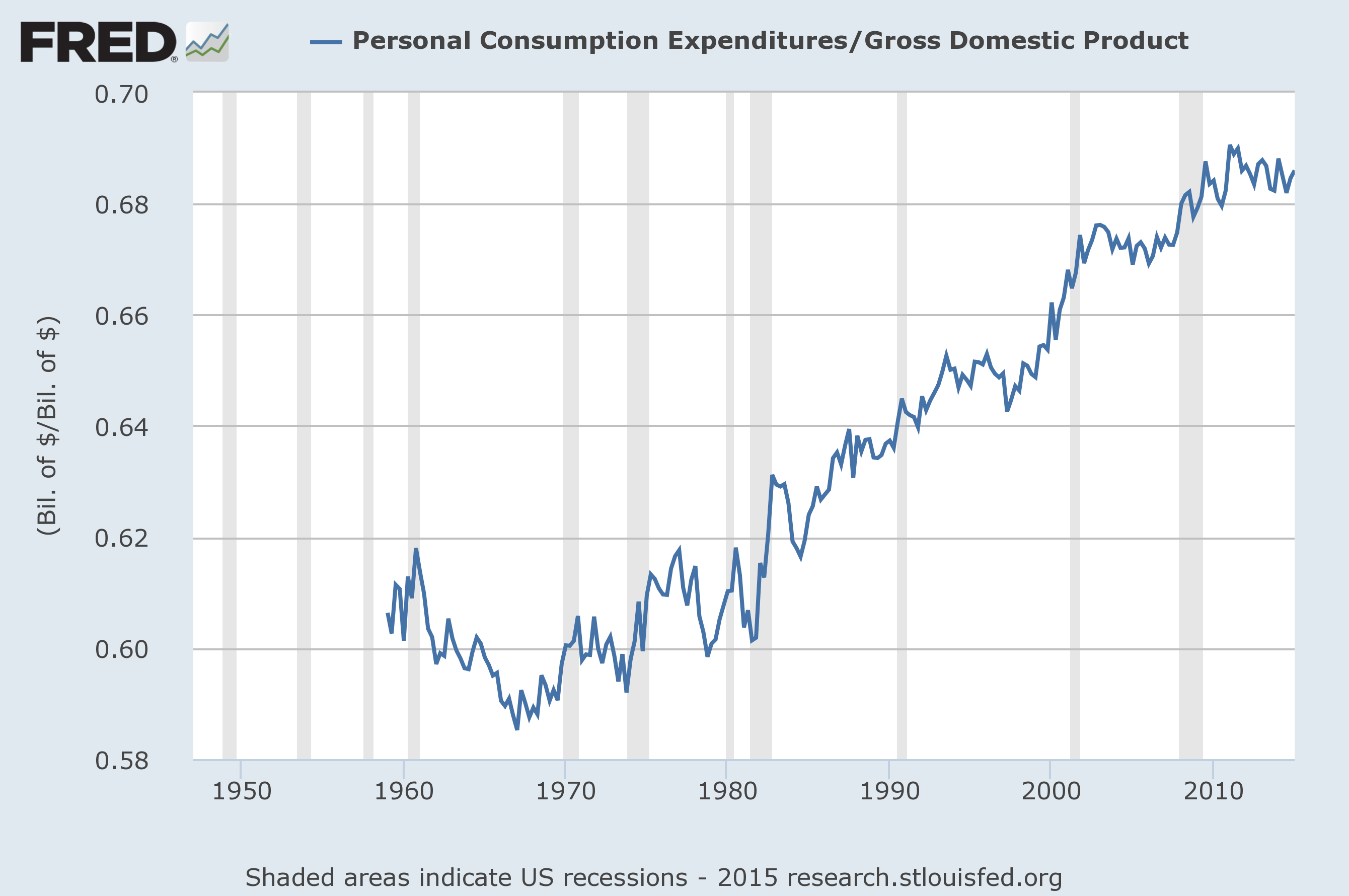

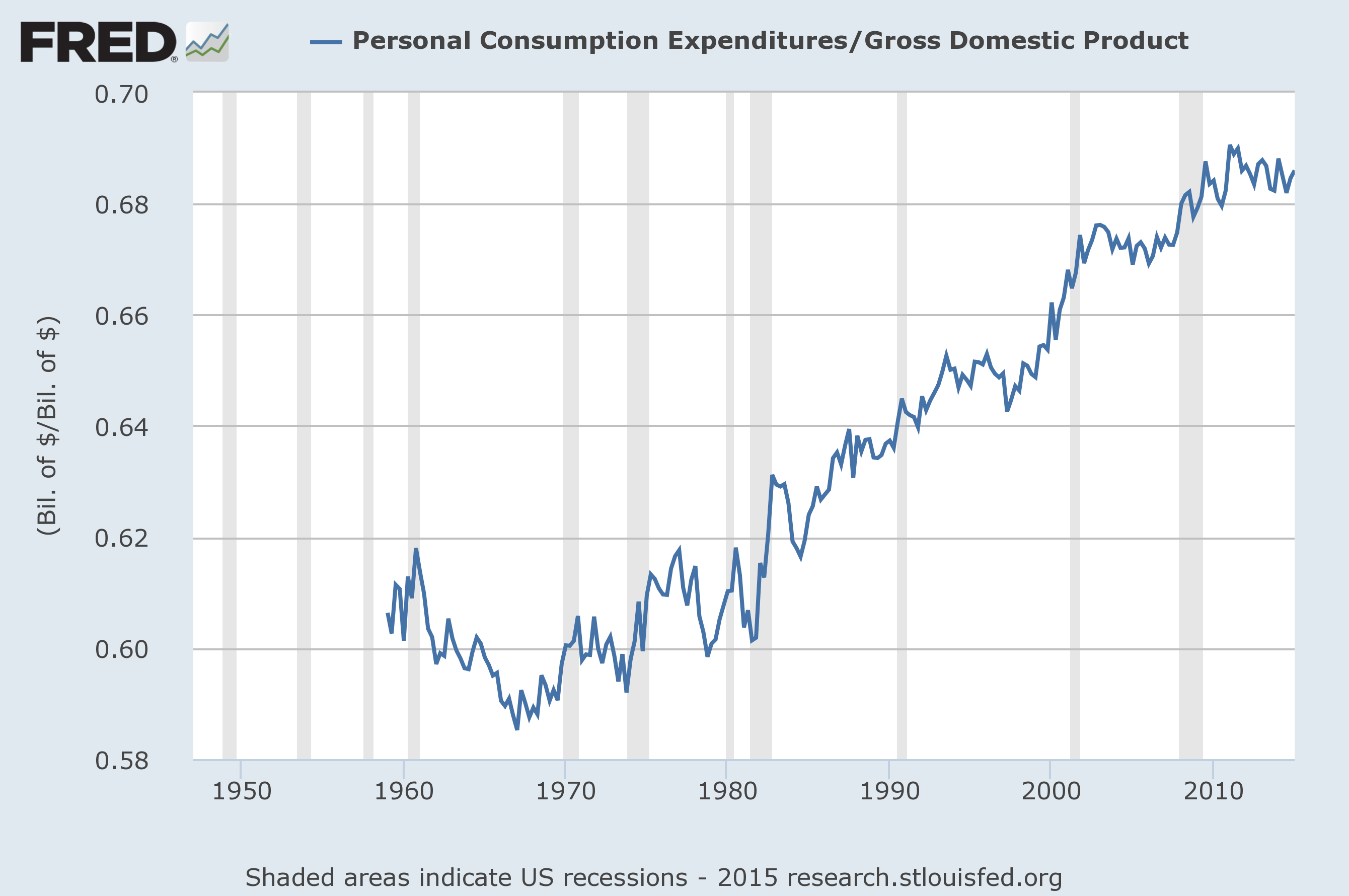

The problem is that the data refuses to agree with his psychoanalysis. As I pointed out yesterday, consumption is actually higher as a share of GDP than it was before the downturn, indicating that fear is not keeping households from consuming in any obvious way.

Samuelson also points to the rise in temporary employment as evidence that firms are scared to commit themselves to permanent employees. The problem with this one is that temporary employment as a share of total employment is just rising back to the levels of the late 1990s, a time when the economy was booming.

If we look at the narrow category of temporary employment agencies, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports the number stood at 2,880,000 in April. That compares to 2,605,000 in December of 1999. Measured as a share of total employment, it stood at 2.03 percent in December of 1999, compared with 2.04 percent of total employment in April.

If we use the somewhat broader category of employment services, BLS reports the number at 3,547,000 in April. That compared to 3,776,000 in December of 1999. Measured as a share of total employment, jobs at employment service agencies fell from 3.77 percent in December of 1999 to 3.55 percent in April.

In short, if employment in temporary agencies is supposed to be a measure of insecurity, it doesn’t appear to be going in the right direction to make Samuelson’s point.

Addendum:

The most obvious explanation for the continuing weakness of the economy is that there is nothing to fill the gap in demand created by a $500 billion annual trade deficit (@ 3 percent of GDP). In the last decade, the demand generated by the housing bubble filled the gap, while in the 1990s the demand from a stock bubble filled the gap. In the absence of another bubble and a refusal to run large budget deficits, there is no obvious source of demand to fill this gap.

Unfortunately this explanation is far too simple to be used by economists or those writing on economy.

Robert Samuelson used his Monday column to tell readers that the problem with the economy is that we are suffering the psychological fallout of the Great Recession:

“My main explanation for this — as I’ve argued before — is the hangover from the 2008-2009 financial crisis and the Great Recession. These events changed economic psychology, precisely because they were unanticipated and horrific. They transcended the experience of most Americans (that is, anyone who hadn’t lived through the Great Depression). Corporate executives and consumers alike became more defensive; they saved and hoarded a bit more. If a novel calamity struck once, it could strike again. They’d better prepare.”

The problem is that the data refuses to agree with his psychoanalysis. As I pointed out yesterday, consumption is actually higher as a share of GDP than it was before the downturn, indicating that fear is not keeping households from consuming in any obvious way.

Samuelson also points to the rise in temporary employment as evidence that firms are scared to commit themselves to permanent employees. The problem with this one is that temporary employment as a share of total employment is just rising back to the levels of the late 1990s, a time when the economy was booming.

If we look at the narrow category of temporary employment agencies, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reports the number stood at 2,880,000 in April. That compares to 2,605,000 in December of 1999. Measured as a share of total employment, it stood at 2.03 percent in December of 1999, compared with 2.04 percent of total employment in April.

If we use the somewhat broader category of employment services, BLS reports the number at 3,547,000 in April. That compared to 3,776,000 in December of 1999. Measured as a share of total employment, jobs at employment service agencies fell from 3.77 percent in December of 1999 to 3.55 percent in April.

In short, if employment in temporary agencies is supposed to be a measure of insecurity, it doesn’t appear to be going in the right direction to make Samuelson’s point.

Addendum:

The most obvious explanation for the continuing weakness of the economy is that there is nothing to fill the gap in demand created by a $500 billion annual trade deficit (@ 3 percent of GDP). In the last decade, the demand generated by the housing bubble filled the gap, while in the 1990s the demand from a stock bubble filled the gap. In the absence of another bubble and a refusal to run large budget deficits, there is no obvious source of demand to fill this gap.

Unfortunately this explanation is far too simple to be used by economists or those writing on economy.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A NYT article reported on a turn to the right of politics in France and in much of the rest of Europe. Remarkably, the piece never once mentioned the decision by the European Central Bank (ECB) to impose a policy of austerity and high unemployment on the continent. Since the mainstream left parties do not want to challenge the ECB, this means they have few plausible routes for reducing unemployment and restoring wage growth for the bulk of the population.

This opens the stage for right-wing nationalist parties, which promise a better economic situation by blaming immigrants for the weak economy. It also forces the traditional left parties to the center since they must accede to the ECB’s demand for austere budgets and labor market reforms.

The United States will be in the same situation if the Federal Reserve Board starts raising interest rates to slow the economy and keep the labor market so weak that most workers cannot get wage gains.

A NYT article reported on a turn to the right of politics in France and in much of the rest of Europe. Remarkably, the piece never once mentioned the decision by the European Central Bank (ECB) to impose a policy of austerity and high unemployment on the continent. Since the mainstream left parties do not want to challenge the ECB, this means they have few plausible routes for reducing unemployment and restoring wage growth for the bulk of the population.

This opens the stage for right-wing nationalist parties, which promise a better economic situation by blaming immigrants for the weak economy. It also forces the traditional left parties to the center since they must accede to the ECB’s demand for austere budgets and labor market reforms.

The United States will be in the same situation if the Federal Reserve Board starts raising interest rates to slow the economy and keep the labor market so weak that most workers cannot get wage gains.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

As the world awaits the final word on the negotiations between Greece and its creditors, it’s worth a quick flashback to 2010 and the report of Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles, the co-chairs of President Obama’s deficit commission. (This report is often referred to as a report of the commission. That is not true. The by-laws clearly state that to issue a report it was necessary to have the support of 12 of the 16 commission members. While no formal vote was ever taken, the co-chairs’ report only had the support of 10 members.)

Anyhow, getting back to matters at hand, one of the Simpson-Bowles proposals was to raise the normal retirement age for Social Security to 69 from its current level of 66 (soon to be 67). The report recognized that many people work in physically demanding and/or dangerous jobs where it would be unreasonable to expect people to work this late in life. It therefore proposed having special lower retirement ages for certain occupations.

The reason this is relevant to Greece is that one of the sticking points at the moment is the reform of Greece’s public pension system. One of the main issues is that the current system allows people in many occupations to start collecting benefits well before the normal retirement age. For example, hairdressers are apparently among this group because they are exposed to dangerous chemicals on the job.

While the Greek system was a universal target of ridicule among serious minded people everywhere, many of these same people embraced the Simpson-Bowles report as a gem of thoughtful, non-partisan, policy-making. The ability to ignore the fact that the supposedly thoughtful Bowles-Simpson gang were advocating the adoption of a pension system subject to universal ridicule is yet another example of the lack of seriousness of the serious people.

As the world awaits the final word on the negotiations between Greece and its creditors, it’s worth a quick flashback to 2010 and the report of Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles, the co-chairs of President Obama’s deficit commission. (This report is often referred to as a report of the commission. That is not true. The by-laws clearly state that to issue a report it was necessary to have the support of 12 of the 16 commission members. While no formal vote was ever taken, the co-chairs’ report only had the support of 10 members.)

Anyhow, getting back to matters at hand, one of the Simpson-Bowles proposals was to raise the normal retirement age for Social Security to 69 from its current level of 66 (soon to be 67). The report recognized that many people work in physically demanding and/or dangerous jobs where it would be unreasonable to expect people to work this late in life. It therefore proposed having special lower retirement ages for certain occupations.

The reason this is relevant to Greece is that one of the sticking points at the moment is the reform of Greece’s public pension system. One of the main issues is that the current system allows people in many occupations to start collecting benefits well before the normal retirement age. For example, hairdressers are apparently among this group because they are exposed to dangerous chemicals on the job.

While the Greek system was a universal target of ridicule among serious minded people everywhere, many of these same people embraced the Simpson-Bowles report as a gem of thoughtful, non-partisan, policy-making. The ability to ignore the fact that the supposedly thoughtful Bowles-Simpson gang were advocating the adoption of a pension system subject to universal ridicule is yet another example of the lack of seriousness of the serious people.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Economists may not be very good at understanding the economy, but they are quite good at finding ways to keep themselves employed, generally at very high wages. The Washington Post treated us to one such make work project as it reported on a change in consumer psychology due to the recession that has left:

“Americans of all ages less willing to inject their money back into the economy in the form of vacations, clothing and nights out.

“It’s a sharp contrast to the 1990s, when consumers spent freely as their wages rose robustly, and the 2000s, when Americans funded more lavish lifestyles with easy access to credit cards and home-equity loans.”

Really? That sounds like a startling development. Let’s see if we can find it in the data.

The chart shows consumption as a percentage of GDP. I went back to the late fifties so folks can see the longer term picture. People are spending far more today relative to the size of the economy than they did in the sixties, seventies, eighties, or even nineties. In fact, consumer expenditures are higher now relative to the size of economy than they were in the housing bubble days.

So, let’s ask about that psychology story. Apparently the concern is that we fell from a ratio of 68.8 percent in the first quarter of last year all the way down to 68.6 percent in the most recent quarter. My guess is that modest decline is best explained by unusually bad weather in the first quarter that discouraged people from shopping and going out for meals. Also, extraordinarily strong car sales in the second half of 2014 probably let to some falloff in the first quarter since people who buy a new car in the fall generally don’t buy another one in the winter.

But hey, I don’t want to see a lot of unemployed economists. There should be lots of work in looking for a plunge in consumption that isn’t there.

Economists may not be very good at understanding the economy, but they are quite good at finding ways to keep themselves employed, generally at very high wages. The Washington Post treated us to one such make work project as it reported on a change in consumer psychology due to the recession that has left:

“Americans of all ages less willing to inject their money back into the economy in the form of vacations, clothing and nights out.

“It’s a sharp contrast to the 1990s, when consumers spent freely as their wages rose robustly, and the 2000s, when Americans funded more lavish lifestyles with easy access to credit cards and home-equity loans.”

Really? That sounds like a startling development. Let’s see if we can find it in the data.

The chart shows consumption as a percentage of GDP. I went back to the late fifties so folks can see the longer term picture. People are spending far more today relative to the size of the economy than they did in the sixties, seventies, eighties, or even nineties. In fact, consumer expenditures are higher now relative to the size of economy than they were in the housing bubble days.

So, let’s ask about that psychology story. Apparently the concern is that we fell from a ratio of 68.8 percent in the first quarter of last year all the way down to 68.6 percent in the most recent quarter. My guess is that modest decline is best explained by unusually bad weather in the first quarter that discouraged people from shopping and going out for meals. Also, extraordinarily strong car sales in the second half of 2014 probably let to some falloff in the first quarter since people who buy a new car in the fall generally don’t buy another one in the winter.

But hey, I don’t want to see a lot of unemployed economists. There should be lots of work in looking for a plunge in consumption that isn’t there.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión