Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post began its editorial on Jeb Bush’s tax cut proposal by telling readers, that it is “worth taking seriously.” Most of the rest of the editorial is telling us the opposite. The basic story is that everyone gets a tax cuts, with the biggest savings going to the wealthy. That is projected to reduce revenue by $3.2 trillion over the next decade (@ 1.5 percent of GDP), but the magic growth elixir will get us back $2.0 trillion of this shortfall.

Paul Krugman and others have beaten up on this story (can they really sell this one yet again?), so I’ll just focus on one aspect I find especially annoying. While the proposal will sharply limit deductions for things like catastrophic medical bills and state and local taxes, it allows the deduction for charitable givings to remain unlimited. (Actually, the current cap of 50 percent of adjusted gross income stays in place.)

I have nothing against charities, but we need to look at this one with clear eyes. The presidents and top executives of many non-profits currently get pay in the high hundreds of thousands of dollars or even millions of dollars. Is it really necessary to subsidize these paychecks with taxpayer dollars?

For example, some hedge fund honcho may give tens of millions of dollars to a foundation that he has created with his college buddy, who runs the show for $2 million a year. Since our hedge funder is in the 43 percent bracket (ignoring their carried interest tax break), taxpayers are effectively picking up $860k of his college buddy’s pay. That’s equal to approximately 500 person-years of food stamps.

Now I want to help struggling foundation presidents as much as the next person, but isn’t there a better use of taxpayer dollars? It doesn’t seem unreasonable to say that if non-profits are going to enjoy tax subsidies that we get to set some rules, such as a cap on what any of its employees can earn.

The president of the United States gets $400k a year. That seems like a reasonable cap for the president and other employees of non-profits. If they can’t find good help for this wage then maybe they aren’t the sort of organization that deserves the taxpayer’s support.

The Washington Post began its editorial on Jeb Bush’s tax cut proposal by telling readers, that it is “worth taking seriously.” Most of the rest of the editorial is telling us the opposite. The basic story is that everyone gets a tax cuts, with the biggest savings going to the wealthy. That is projected to reduce revenue by $3.2 trillion over the next decade (@ 1.5 percent of GDP), but the magic growth elixir will get us back $2.0 trillion of this shortfall.

Paul Krugman and others have beaten up on this story (can they really sell this one yet again?), so I’ll just focus on one aspect I find especially annoying. While the proposal will sharply limit deductions for things like catastrophic medical bills and state and local taxes, it allows the deduction for charitable givings to remain unlimited. (Actually, the current cap of 50 percent of adjusted gross income stays in place.)

I have nothing against charities, but we need to look at this one with clear eyes. The presidents and top executives of many non-profits currently get pay in the high hundreds of thousands of dollars or even millions of dollars. Is it really necessary to subsidize these paychecks with taxpayer dollars?

For example, some hedge fund honcho may give tens of millions of dollars to a foundation that he has created with his college buddy, who runs the show for $2 million a year. Since our hedge funder is in the 43 percent bracket (ignoring their carried interest tax break), taxpayers are effectively picking up $860k of his college buddy’s pay. That’s equal to approximately 500 person-years of food stamps.

Now I want to help struggling foundation presidents as much as the next person, but isn’t there a better use of taxpayer dollars? It doesn’t seem unreasonable to say that if non-profits are going to enjoy tax subsidies that we get to set some rules, such as a cap on what any of its employees can earn.

The president of the United States gets $400k a year. That seems like a reasonable cap for the president and other employees of non-profits. If they can’t find good help for this wage then maybe they aren’t the sort of organization that deserves the taxpayer’s support.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Sorry folks, but sometimes politicians and political figures say things for public consumption, not because they actually reflect reality. This is why reporters should tell us what these figures say, not to assume that what they say reflects the truth.

Therefore, when Attorney General Loretta Lynch sent out a memo saying that the Justice Department would seek criminal prosecutions of individuals in cases of white collar crime, the NYT should have reported that she sent out a memo. It should not have an article headlined, “Justice Department sets sights on Wall Street executives.” Of course the NYT does not know that the Justice Department will actually go through with criminal prosecutions, it just knows that the Attorney General sent out a memo indicating that she wants it to. We will know for sure that this memo accurately reflects policy when we see high level corporate officials indicted for criminal activity.

Thanks to Robert Sadin for calling this one to my attention.

Sorry folks, but sometimes politicians and political figures say things for public consumption, not because they actually reflect reality. This is why reporters should tell us what these figures say, not to assume that what they say reflects the truth.

Therefore, when Attorney General Loretta Lynch sent out a memo saying that the Justice Department would seek criminal prosecutions of individuals in cases of white collar crime, the NYT should have reported that she sent out a memo. It should not have an article headlined, “Justice Department sets sights on Wall Street executives.” Of course the NYT does not know that the Justice Department will actually go through with criminal prosecutions, it just knows that the Attorney General sent out a memo indicating that she wants it to. We will know for sure that this memo accurately reflects policy when we see high level corporate officials indicted for criminal activity.

Thanks to Robert Sadin for calling this one to my attention.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

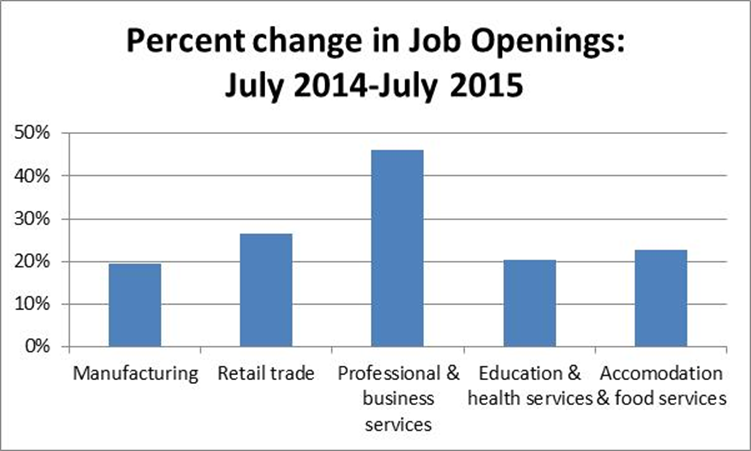

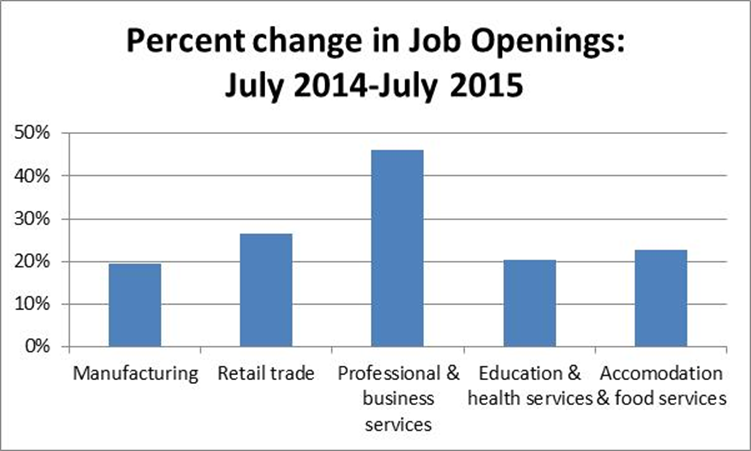

The Labor Department released new data this morning on job openings and turnover. The release showed a big jump in openings in July compared with June or July of 2014. In the past this has been taken as evidence of the economy’s strength and also as an indication that employers are having problems get workers with the needed skills.

One problem with this story is that many of the openings are showing up in retail trade and restaurants, which are not areas where we ordinarily think the skill requirements are very high (which does not mean that the work is not difficult). The chart below shows most of the sectors responsible for the jump in openings. The biggest rise is professional and business services, which includes many highly skilled occupations, but also includes temp help and custodians. The point here is that it is not clear what is going on in these markets based on the rise in openings. If employers were really having trouble getting the workers they need then they should be offering higher pay. Thus far, they are not.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The Labor Department released new data this morning on job openings and turnover. The release showed a big jump in openings in July compared with June or July of 2014. In the past this has been taken as evidence of the economy’s strength and also as an indication that employers are having problems get workers with the needed skills.

One problem with this story is that many of the openings are showing up in retail trade and restaurants, which are not areas where we ordinarily think the skill requirements are very high (which does not mean that the work is not difficult). The chart below shows most of the sectors responsible for the jump in openings. The biggest rise is professional and business services, which includes many highly skilled occupations, but also includes temp help and custodians. The point here is that it is not clear what is going on in these markets based on the rise in openings. If employers were really having trouble getting the workers they need then they should be offering higher pay. Thus far, they are not.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

David Brooks discussed the rise of Jeremy Corbyn on the left in the Labor Party in the United Kingdom and Bernie Sanders on the left in the United States, along with Donald Trump and Ben Carson on the right. He argues that none of these people could conceivably win election. He therefore concludes that their support must stem from a psychological problem which he identifies as expressive individualism.

This is an interesting view. Of course, Brooks’ assessment of who is electable may not be right. For example, the Democrats have often nominated centrist figures, such as Michael Dukakis, because they were ostensibly more electable than their more progressive alternatives. While we can’t know the counterfactual, there is little logic in picking a candidate whose views you do not share, because they are electable, when in fact they are not.

But the more important question ignored in Brooks’ analysis is how people are supposed to respond when the party they have supported consistently pursues policies at odds with fundamental principles of their core constituencies. In the case of the Labor Party in the U.K., and the administrations of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama in the United States, the wealthy have received the overwhelming majority of the benefits of economic growth.

This has been due to policies that have favored the financial sector and trade deals that have disadvantaged ordinary workers to benefit major corporate interests. In both countries, there was no effort to prosecute bankers who had violated the law during the housing bubble years. The Clinton administration pushed to remove constraints on the financial sector, even while leaving its government guarantees in place. President Obama has opposed a financial transactions tax in the United States, which would take tens of billions annually out of the pockets of the financial industry. His administration has also worked actively to block the introduction of such a tax in Europe.

He has also pushed the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which would increase the cost of prescription drugs for the countries in the agreement. It is also likely to worsen the U.S. trade deficit in manufactured goods, since more foreign earnings would be diverted to be paying for drugs and other patent-protected products. Of course the Clinton administration explicitly pushed for the over-valued dollar that is the origin of the large U.S. trade deficits.

It is impressive to see Brooks argue that trying to turn the Democratic Party toward an agenda that supports workers rather than the rich is a psychological problem.

Note: spelling for Jeremy Corbyn has been corrected, thank folks.

David Brooks discussed the rise of Jeremy Corbyn on the left in the Labor Party in the United Kingdom and Bernie Sanders on the left in the United States, along with Donald Trump and Ben Carson on the right. He argues that none of these people could conceivably win election. He therefore concludes that their support must stem from a psychological problem which he identifies as expressive individualism.

This is an interesting view. Of course, Brooks’ assessment of who is electable may not be right. For example, the Democrats have often nominated centrist figures, such as Michael Dukakis, because they were ostensibly more electable than their more progressive alternatives. While we can’t know the counterfactual, there is little logic in picking a candidate whose views you do not share, because they are electable, when in fact they are not.

But the more important question ignored in Brooks’ analysis is how people are supposed to respond when the party they have supported consistently pursues policies at odds with fundamental principles of their core constituencies. In the case of the Labor Party in the U.K., and the administrations of Bill Clinton and Barack Obama in the United States, the wealthy have received the overwhelming majority of the benefits of economic growth.

This has been due to policies that have favored the financial sector and trade deals that have disadvantaged ordinary workers to benefit major corporate interests. In both countries, there was no effort to prosecute bankers who had violated the law during the housing bubble years. The Clinton administration pushed to remove constraints on the financial sector, even while leaving its government guarantees in place. President Obama has opposed a financial transactions tax in the United States, which would take tens of billions annually out of the pockets of the financial industry. His administration has also worked actively to block the introduction of such a tax in Europe.

He has also pushed the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which would increase the cost of prescription drugs for the countries in the agreement. It is also likely to worsen the U.S. trade deficit in manufactured goods, since more foreign earnings would be diverted to be paying for drugs and other patent-protected products. Of course the Clinton administration explicitly pushed for the over-valued dollar that is the origin of the large U.S. trade deficits.

It is impressive to see Brooks argue that trying to turn the Democratic Party toward an agenda that supports workers rather than the rich is a psychological problem.

Note: spelling for Jeremy Corbyn has been corrected, thank folks.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is what it told readers in its article writing up the data. The piece indicated surprise that wages are not rising more rapidly given the relatively low unemployment rate:

“Over the past 40 years, unemployment has almost never been as low as it is today, with the exception of a few years in the late 1990s.”

This part is not quite right. The unemployment rate was below the 5.1 percent rate reported for August from May of 2005 until April of 2007, so an unemployment rate this low is not quite that rare.

The other part of the story that has been widely noted is that employment rate, the percentage of the population that has jobs, is down by more than three percentage points from its pre-recession level. This is true even if we just look at prime-age (ages 25-54) workers.

Since no one has a very good story as to why 3 million plus people just decided that they didn’t feel like working, the most obvious explanation is that these are people who still want to work but have given up looking for jobs because of the weak state of the labor market.

It is also worth noting that if this decline in the labor force reflects something other than the weakness of the labor market, virtually no one saw it coming before the recession. The economists who want to blame some supply-side factor as the cause of the reduction in the size of the labor force therefore need to explain why they were unable to see this factor before the recession. They also need to explain why anyone should believe their understanding of the economy is better today than it was in 2007.

That is what it told readers in its article writing up the data. The piece indicated surprise that wages are not rising more rapidly given the relatively low unemployment rate:

“Over the past 40 years, unemployment has almost never been as low as it is today, with the exception of a few years in the late 1990s.”

This part is not quite right. The unemployment rate was below the 5.1 percent rate reported for August from May of 2005 until April of 2007, so an unemployment rate this low is not quite that rare.

The other part of the story that has been widely noted is that employment rate, the percentage of the population that has jobs, is down by more than three percentage points from its pre-recession level. This is true even if we just look at prime-age (ages 25-54) workers.

Since no one has a very good story as to why 3 million plus people just decided that they didn’t feel like working, the most obvious explanation is that these are people who still want to work but have given up looking for jobs because of the weak state of the labor market.

It is also worth noting that if this decline in the labor force reflects something other than the weakness of the labor market, virtually no one saw it coming before the recession. The economists who want to blame some supply-side factor as the cause of the reduction in the size of the labor force therefore need to explain why they were unable to see this factor before the recession. They also need to explain why anyone should believe their understanding of the economy is better today than it was in 2007.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Most of the reporting on China and its current economic problems refers to it as the world’s second largest economy. This is true if its GDP is measured on a currency conversion basis, in other words taking its GDP and effectively converting it into dollars at the official exchange rate.

However economists more typically use purchasing power parity measures of GDP. These involve using a common set of prices for goods and services in all countries. By this measure China’s GDP is already more than 5 percent larger than the GDP of the United States, not counting Hong Kong.

This point is important in understanding China’s impact on the world economy. If its economy slows significantly, the reduction in its imports of oil and other inputs will reflect its size based on its purchasing power parity GDP, not the exchange rate measure. This is why the recent uncertainty in China is having so much impact on the price of oil and other commodities. The reporting should acknowledge this fact.

Most of the reporting on China and its current economic problems refers to it as the world’s second largest economy. This is true if its GDP is measured on a currency conversion basis, in other words taking its GDP and effectively converting it into dollars at the official exchange rate.

However economists more typically use purchasing power parity measures of GDP. These involve using a common set of prices for goods and services in all countries. By this measure China’s GDP is already more than 5 percent larger than the GDP of the United States, not counting Hong Kong.

This point is important in understanding China’s impact on the world economy. If its economy slows significantly, the reduction in its imports of oil and other inputs will reflect its size based on its purchasing power parity GDP, not the exchange rate measure. This is why the recent uncertainty in China is having so much impact on the price of oil and other commodities. The reporting should acknowledge this fact.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It is amazing how economic reporters and many economists continue to be obsessed with the topic of deflation. They seem to hold the view that when inflation crosses zero and turns negative, then something happens. This is in spite of the fact that there is zero (as in none) reason to believe this would be the case in theory and zero evidence that it is the case in reality.

Yet, we once again see the NYT tell readers in a piece on the current agenda of European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi:

“Inflation, at 0.2 percent in August, was unchanged from June and July. The rate is still well short of the European Central Bank’s official target of just below 2 percent.

“Some economists remain concerned that the eurozone could yet slip into deflation, which has already infected some eurozone countries like Greece.”

Suppose that inflation went from 0.2 percent to -0.2 percent so that the euro zone was experiencing deflation. Why would this be any worse than a decline from 0.6 percent to 0.2 percent? The problem is that the inflation rate is too low. Any drop in the inflation rate makes the situation worse. It has the effect of raising real interest rates and raising the real value of debt, but crossing zero doesn’t matter, the drop in the inflation rate is all that matters.

There is a story that can be told of spiraling deflation, where deflation feeds on itself, except we never see this. Even Japan never experienced spiraling deflation. We did have something like spiraling deflation at the start of the Great Depression, but there is little reason to believe any countries face this threat now and certainly not from having their inflation rate slip a few tenths of a percentage point below zero. (As I’ve pointed out in times past, our measurements are not even accurate enough to ensure that a reported 0.2 percent inflation rate is in fact above zero.)

Anyhow, the deflation obsession continues. I suppose like the belief in a flat earth, it is impervious to evidence.

It is probably worth mentioning that the deflation in Greece is not seen by the ECB as a problem. It is by design. Greece needs to regain competitiveness with Germany and other northern euro zone countries. This could be done by these countries having higher inflation rates, for example as a result of larger budget deficits in these countries. The euro zone has quite explicitly chosen to not go this route. As a result, the only route for Greece to regain competitiveness is through deflation.

It is amazing how economic reporters and many economists continue to be obsessed with the topic of deflation. They seem to hold the view that when inflation crosses zero and turns negative, then something happens. This is in spite of the fact that there is zero (as in none) reason to believe this would be the case in theory and zero evidence that it is the case in reality.

Yet, we once again see the NYT tell readers in a piece on the current agenda of European Central Bank (ECB) President Mario Draghi:

“Inflation, at 0.2 percent in August, was unchanged from June and July. The rate is still well short of the European Central Bank’s official target of just below 2 percent.

“Some economists remain concerned that the eurozone could yet slip into deflation, which has already infected some eurozone countries like Greece.”

Suppose that inflation went from 0.2 percent to -0.2 percent so that the euro zone was experiencing deflation. Why would this be any worse than a decline from 0.6 percent to 0.2 percent? The problem is that the inflation rate is too low. Any drop in the inflation rate makes the situation worse. It has the effect of raising real interest rates and raising the real value of debt, but crossing zero doesn’t matter, the drop in the inflation rate is all that matters.

There is a story that can be told of spiraling deflation, where deflation feeds on itself, except we never see this. Even Japan never experienced spiraling deflation. We did have something like spiraling deflation at the start of the Great Depression, but there is little reason to believe any countries face this threat now and certainly not from having their inflation rate slip a few tenths of a percentage point below zero. (As I’ve pointed out in times past, our measurements are not even accurate enough to ensure that a reported 0.2 percent inflation rate is in fact above zero.)

Anyhow, the deflation obsession continues. I suppose like the belief in a flat earth, it is impervious to evidence.

It is probably worth mentioning that the deflation in Greece is not seen by the ECB as a problem. It is by design. Greece needs to regain competitiveness with Germany and other northern euro zone countries. This could be done by these countries having higher inflation rates, for example as a result of larger budget deficits in these countries. The euro zone has quite explicitly chosen to not go this route. As a result, the only route for Greece to regain competitiveness is through deflation.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a piece on how Mexico’s economy remains weak and the government is again plagued by corruption. At one point it comments that:

“Growth has been slower under Mr. Peña Nieto’s presidency than the annual 2.3 percent average in the two decades before he took office.”

It is worth noting that a 2.3 percent growth rate is extremely weak for a developing country. It means that Mexico was actually falling further behind the United States even before the slowdown under President Nieto. Furthermore, as the article points out, it appears that workers are seeing little or no benefit from even this limited growth, as wages remain quite low.

Last year marked the twentieth anniversary of the implementation of NAFTA. At the time there was much celebration in the media and among economists anxious to pronounce the deal a huge success. While it is always possible that Mexico’s economy would have performed even worse without NAFTA, its actual record is not much to boast about.

It is worth singling out the Washington Post in this context which periodically celebrates the rise of the middle class in Mexico in the post-NAFTA era. The Post famously invented numbers to make its pro-NAFTA case, telling readers back in 2007 that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled since 1987. The actual increase was 83 percent. It has never bothered to correct this one.

The NYT had a piece on how Mexico’s economy remains weak and the government is again plagued by corruption. At one point it comments that:

“Growth has been slower under Mr. Peña Nieto’s presidency than the annual 2.3 percent average in the two decades before he took office.”

It is worth noting that a 2.3 percent growth rate is extremely weak for a developing country. It means that Mexico was actually falling further behind the United States even before the slowdown under President Nieto. Furthermore, as the article points out, it appears that workers are seeing little or no benefit from even this limited growth, as wages remain quite low.

Last year marked the twentieth anniversary of the implementation of NAFTA. At the time there was much celebration in the media and among economists anxious to pronounce the deal a huge success. While it is always possible that Mexico’s economy would have performed even worse without NAFTA, its actual record is not much to boast about.

It is worth singling out the Washington Post in this context which periodically celebrates the rise of the middle class in Mexico in the post-NAFTA era. The Post famously invented numbers to make its pro-NAFTA case, telling readers back in 2007 that Mexico’s GDP had quadrupled since 1987. The actual increase was 83 percent. It has never bothered to correct this one.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión