• Budget and National DebtDebtEconomic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperaciónUnited StatesEE. UU.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Economics famously suffers from a “which way is up?” problem. The issue is whether an economy is suffering from too much demand or too little demand. On its face, that seems like it should be a very simple question, but in fact it can be complicated and people often get it wrong, with very serious consequences.

The Great Depression was the classic too little demand story. We had millions of people out of work through the decade of the 1930s because there was not enough demand in the economy. With the benefit of hindsight, or a good Keynesian understanding of the economy, this demand problem is very clear, but it did not seem that way to many people living at the time.

Most immediately, people saw families who didn’t have food, adequate clothing, or housing. That looks a lot like a problem of having too little of the things that are necessary to meet society’s needs.

But the reality was the opposite. We know this for certain because once the government spent lots of money, the economy was able to meet these needs and considerably more.

Unfortunately, it took World War II to provide the political will to get the government to spend the money needed to get the economy back to full employment. But, if we had the political will to spend the money, we could have ended the depression in 1931 instead of 1941. The key point was the need to spend lots of money; it didn’t have to be spending on a war. (This is why all the talk of a Second Great Depression around the 2008-09 financial crisis is so silly. We know how to spend money. That’s all we need to do to avoid a Second Great Depression.)

We have had many other instances of too little demand in the last 80 years, most obviously in the Great Recession and the slow recovery that followed. If we had a larger stimulus and more government spending in the years following the Great Recession, the labor market could have recovered more quickly, bringing us back to full employment years earlier, although we did finally reach something close to full employment in the year just before the pandemic.

During the pandemic we did see the opposite problem, where we had too much demand. This was due both to the fact that support packages the government used to keep people whole (enhanced unemployment benefits, the Paycheck Protection Program, and the checks) put a lot of money in people’s pockets, and that the pandemic itself crippled supply. The strong demand, coupled with the reduction in supply, gave us the burst of inflation in 2021-22 that is now receding.

David Brooks Struggles with the Problem

Okay, so now that we know the players, let’s look at how David Brooks struggles with the problem in his column this morning. Brooks tells readers about the “second phase” of Biden’s presidency.

“Today, its main purpose is to prepare the nation for a period of accelerating and explosive change. ….

“The information age is accelerating and growing more disruptive. The first cause is artificial intelligence. A.I. will produce pervasive breakthroughs and threats that none of us can now predict. Another cause is the emerging cold war with China. This will produce a remorseless technological competition that will turbocharge developments in biotech, energy, chip manufacturing, trade flows, political alliances and many other spheres.

“We’re living in the first stages of what my colleague Thomas Friedman a few years ago called ‘the age of acceleration,’ an age of both stunning advances and horrific dislocations.”

This is all very dramatic, but the basic point here is that Brooks is telling us that we are entering an era of rapid technological change. That means rapid productivity growth. AI and other technologies will allow us to produce much more output for each hour of work. This means that the economy should be able to produce much more in the years ahead than it does today.

That raises the risk that we will have too little demand. Workers laid off as a result of AI and other technological developments may not get re-employed. The government will have to provide generous benefits and/or increase spending in other areas to keep the economy near full employment.

I’ll confess to some skepticism about these claims of a technological revolution (we’ve been hearing them for three decades now), but this is at least a clear story. Technology will revolutionize the economy and make it far more productive than it is today.

But then Brooks takes a U-turn and tells us that we have to worry about too much demand.

“We’re going to need governments that are able to pivot quickly and throw tidal waves of money at suddenly emerging problems, from technologically driven mass unemployment to war in the Pacific.

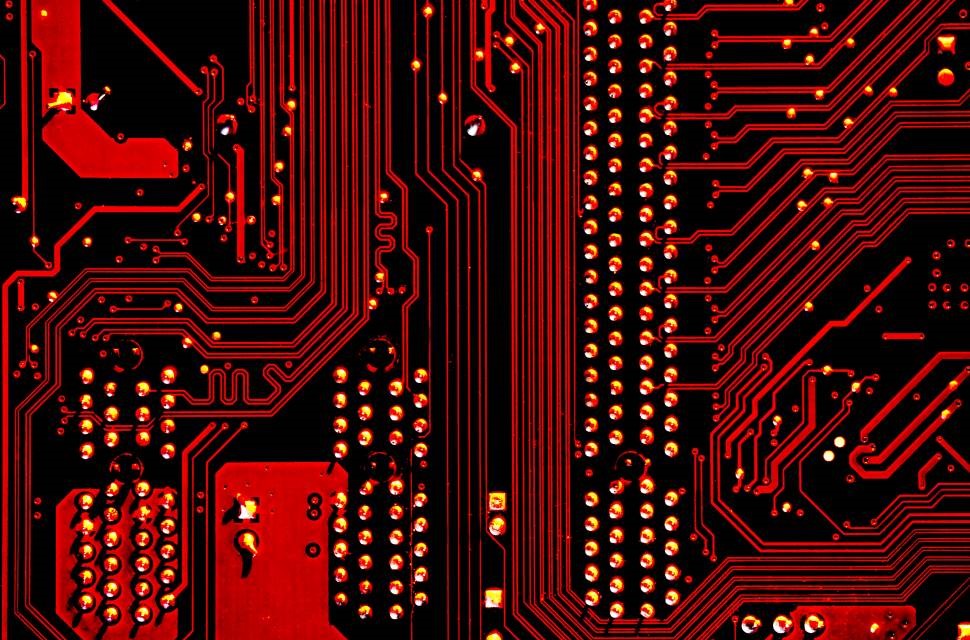

“When Covid hit, the United States successfully pivoted and threw trillions of dollars at that problem. But the United States may not be able to mobilize that kind of response in the future. That’s because we’re now manacled by debt. …..

“The United States is projected to spend roughly $640 billion this year merely paying interest on that debt, a figure that is expected to more than double by 2033. That’s about the time the Social Security Trust Fund will become insolvent, requiring even more gigantic cash infusions to keep the program going.”

Brooks is very explicitly describing an economy where we would lack the ability to produce the goods and services necessary to meet society’s needs. This is 180 degrees at odds with the story of the “age of acceleration,” where technological breakthroughs are making us hugely more productive.

If the economy is transformed in the way Brooks is predicting, there is no reason the government couldn’t spend whatever money is needed to accommodate the transition he is describing. We need not be worried about inflation if a technological revolution is causing huge reductions in production costs and there is an enormous amount of excess capacity in the economy.

Will the ratio of debt to GDP rise? It could, although it is hard to say for sure, if GDP were to rise rapidly as Brooks seems to expect. But suppose the ratio does rise; so what? Japan has a debt to GDP ratio of 250 percent. It has been trying to raise its inflation rate for two decades. The interest rate on its long-term government debt is near zero. Where’s the problem?

Keeping Our Horror Stories Straight

To be clear, I am skeptical, but hopeful, about Brooks’ technological revolution. AI and other technologies could lead to an acceleration of productivity growth. But, if we do see the revolution that he and his colleague Thomas Friedman seem to expect, then we do not have to worry about debts and deficits.

Those are concerns for an economy with slow growth, where too much demand really is the problem. If the economy’s productive capacities are going through the roof, there is no need to worry about how it will pay for my Social Security.

Economics famously suffers from a “which way is up?” problem. The issue is whether an economy is suffering from too much demand or too little demand. On its face, that seems like it should be a very simple question, but in fact it can be complicated and people often get it wrong, with very serious consequences.

The Great Depression was the classic too little demand story. We had millions of people out of work through the decade of the 1930s because there was not enough demand in the economy. With the benefit of hindsight, or a good Keynesian understanding of the economy, this demand problem is very clear, but it did not seem that way to many people living at the time.

Most immediately, people saw families who didn’t have food, adequate clothing, or housing. That looks a lot like a problem of having too little of the things that are necessary to meet society’s needs.

But the reality was the opposite. We know this for certain because once the government spent lots of money, the economy was able to meet these needs and considerably more.

Unfortunately, it took World War II to provide the political will to get the government to spend the money needed to get the economy back to full employment. But, if we had the political will to spend the money, we could have ended the depression in 1931 instead of 1941. The key point was the need to spend lots of money; it didn’t have to be spending on a war. (This is why all the talk of a Second Great Depression around the 2008-09 financial crisis is so silly. We know how to spend money. That’s all we need to do to avoid a Second Great Depression.)

We have had many other instances of too little demand in the last 80 years, most obviously in the Great Recession and the slow recovery that followed. If we had a larger stimulus and more government spending in the years following the Great Recession, the labor market could have recovered more quickly, bringing us back to full employment years earlier, although we did finally reach something close to full employment in the year just before the pandemic.

During the pandemic we did see the opposite problem, where we had too much demand. This was due both to the fact that support packages the government used to keep people whole (enhanced unemployment benefits, the Paycheck Protection Program, and the checks) put a lot of money in people’s pockets, and that the pandemic itself crippled supply. The strong demand, coupled with the reduction in supply, gave us the burst of inflation in 2021-22 that is now receding.

David Brooks Struggles with the Problem

Okay, so now that we know the players, let’s look at how David Brooks struggles with the problem in his column this morning. Brooks tells readers about the “second phase” of Biden’s presidency.

“Today, its main purpose is to prepare the nation for a period of accelerating and explosive change. ….

“The information age is accelerating and growing more disruptive. The first cause is artificial intelligence. A.I. will produce pervasive breakthroughs and threats that none of us can now predict. Another cause is the emerging cold war with China. This will produce a remorseless technological competition that will turbocharge developments in biotech, energy, chip manufacturing, trade flows, political alliances and many other spheres.

“We’re living in the first stages of what my colleague Thomas Friedman a few years ago called ‘the age of acceleration,’ an age of both stunning advances and horrific dislocations.”

This is all very dramatic, but the basic point here is that Brooks is telling us that we are entering an era of rapid technological change. That means rapid productivity growth. AI and other technologies will allow us to produce much more output for each hour of work. This means that the economy should be able to produce much more in the years ahead than it does today.

That raises the risk that we will have too little demand. Workers laid off as a result of AI and other technological developments may not get re-employed. The government will have to provide generous benefits and/or increase spending in other areas to keep the economy near full employment.

I’ll confess to some skepticism about these claims of a technological revolution (we’ve been hearing them for three decades now), but this is at least a clear story. Technology will revolutionize the economy and make it far more productive than it is today.

But then Brooks takes a U-turn and tells us that we have to worry about too much demand.

“We’re going to need governments that are able to pivot quickly and throw tidal waves of money at suddenly emerging problems, from technologically driven mass unemployment to war in the Pacific.

“When Covid hit, the United States successfully pivoted and threw trillions of dollars at that problem. But the United States may not be able to mobilize that kind of response in the future. That’s because we’re now manacled by debt. …..

“The United States is projected to spend roughly $640 billion this year merely paying interest on that debt, a figure that is expected to more than double by 2033. That’s about the time the Social Security Trust Fund will become insolvent, requiring even more gigantic cash infusions to keep the program going.”

Brooks is very explicitly describing an economy where we would lack the ability to produce the goods and services necessary to meet society’s needs. This is 180 degrees at odds with the story of the “age of acceleration,” where technological breakthroughs are making us hugely more productive.

If the economy is transformed in the way Brooks is predicting, there is no reason the government couldn’t spend whatever money is needed to accommodate the transition he is describing. We need not be worried about inflation if a technological revolution is causing huge reductions in production costs and there is an enormous amount of excess capacity in the economy.

Will the ratio of debt to GDP rise? It could, although it is hard to say for sure, if GDP were to rise rapidly as Brooks seems to expect. But suppose the ratio does rise; so what? Japan has a debt to GDP ratio of 250 percent. It has been trying to raise its inflation rate for two decades. The interest rate on its long-term government debt is near zero. Where’s the problem?

Keeping Our Horror Stories Straight

To be clear, I am skeptical, but hopeful, about Brooks’ technological revolution. AI and other technologies could lead to an acceleration of productivity growth. But, if we do see the revolution that he and his colleague Thomas Friedman seem to expect, then we do not have to worry about debts and deficits.

Those are concerns for an economy with slow growth, where too much demand really is the problem. If the economy’s productive capacities are going through the roof, there is no need to worry about how it will pay for my Social Security.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

A friend reminded me that the Treasury controls more than $500 billion in gold reserves. The President has the legal authority to direct the Treasury to sell these reserves any time he likes. This would not be enough to cover a full year, given the size of the current deficit, but it certainly could delay the X-date by several months.

Anyone have any ideas why selling gold is not in the mix of possible courses of action?

A friend reminded me that the Treasury controls more than $500 billion in gold reserves. The President has the legal authority to direct the Treasury to sell these reserves any time he likes. This would not be enough to cover a full year, given the size of the current deficit, but it certainly could delay the X-date by several months.

Anyone have any ideas why selling gold is not in the mix of possible courses of action?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• COVID-19CoronavirusEconomic Crisis and RecoveryCrisis económica y recuperaciónEconomic GrowthEl DesarolloInflationUnited StatesEE. UU.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Economic GrowthEl DesarolloInequalityLa DesigualdadTechnology

We have long known that people in policy debates have difficulty with arithmetic and basic logic. We got yet another example today in the New York Times.

The NYT profiled Geoffrey Hinton, who recently resigned as head of AI technology at Google. The piece identified him as “the godfather of AI.” The piece reports on Hinton’s concerns about the risks of AI, one of which is its implications for the job market.

“He is also worried that A.I. technologies will in time upend the job market. Today, chatbots like ChatGPT tend to complement human workers, but they could replace paralegals, personal assistants, translators and others who handle rote tasks. ‘It takes away the drudge work,’ he said. ‘It might take away more than that.’”

The implication of this paragraph is that AI will lead to a massive uptick in productivity growth. That would be great news from the standpoint of the economic problems that have been featured prominently in public debates in recent years.

Most immediately, soaring productivity would hugely reduce the risks of inflation. Costs would plummet as fewer workers would be needed in large sectors of the economy, which presumably would mean downward pressure on prices as well. (Prices have generally followed costs. Most of the upward redistribution of the last four decades has been within the wage distribution, not from labor to capital.)

A massive surge in productivity would also mean that we don’t have to worry at all about the Social Security “crisis.” The drop in the ratio of workers to retirees would be hugely offset by the increased productivity of each worker. (The impact of recent and projected future productivity growth already swamps the impact of demographics, but a surge in productivity growth would make the impact of demographics laughably trivial.)

It is also worth noting that any concerns about technology leading to more inequality are wrongheaded. If AI does lead to more inequality, it will be due to how we have chosen to regulate AI, not AI itself.

People gain from technology as a result of how we set rules on intellectual products, like granting patent and copyright monopolies and allowing non-disclosure agreements to be enforceable contracts. If we had a world without these sorts of restrictions, it is almost impossible to imagine a scenario in which AI, or other recent technologies, would lead to inequality. (Imagine all Microsoft software was free. How rich is Bill Gates?)

If AI leads to more inequality, it will be because of the rules we have put in place surrounding AI, not AI itself. It is understandable that the people who gain from this inequality would like to blame the technology, not rules which can be changed, but it is not true. Unfortunately, people involved in policy debates don’t seem able to recognize this point.

We have long known that people in policy debates have difficulty with arithmetic and basic logic. We got yet another example today in the New York Times.

The NYT profiled Geoffrey Hinton, who recently resigned as head of AI technology at Google. The piece identified him as “the godfather of AI.” The piece reports on Hinton’s concerns about the risks of AI, one of which is its implications for the job market.

“He is also worried that A.I. technologies will in time upend the job market. Today, chatbots like ChatGPT tend to complement human workers, but they could replace paralegals, personal assistants, translators and others who handle rote tasks. ‘It takes away the drudge work,’ he said. ‘It might take away more than that.’”

The implication of this paragraph is that AI will lead to a massive uptick in productivity growth. That would be great news from the standpoint of the economic problems that have been featured prominently in public debates in recent years.

Most immediately, soaring productivity would hugely reduce the risks of inflation. Costs would plummet as fewer workers would be needed in large sectors of the economy, which presumably would mean downward pressure on prices as well. (Prices have generally followed costs. Most of the upward redistribution of the last four decades has been within the wage distribution, not from labor to capital.)

A massive surge in productivity would also mean that we don’t have to worry at all about the Social Security “crisis.” The drop in the ratio of workers to retirees would be hugely offset by the increased productivity of each worker. (The impact of recent and projected future productivity growth already swamps the impact of demographics, but a surge in productivity growth would make the impact of demographics laughably trivial.)

It is also worth noting that any concerns about technology leading to more inequality are wrongheaded. If AI does lead to more inequality, it will be due to how we have chosen to regulate AI, not AI itself.

People gain from technology as a result of how we set rules on intellectual products, like granting patent and copyright monopolies and allowing non-disclosure agreements to be enforceable contracts. If we had a world without these sorts of restrictions, it is almost impossible to imagine a scenario in which AI, or other recent technologies, would lead to inequality. (Imagine all Microsoft software was free. How rich is Bill Gates?)

If AI leads to more inequality, it will be because of the rules we have put in place surrounding AI, not AI itself. It is understandable that the people who gain from this inequality would like to blame the technology, not rules which can be changed, but it is not true. Unfortunately, people involved in policy debates don’t seem able to recognize this point.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I’m impressed. Most reporters might just know what politicians say and do, but New York Times reporters can apparently know their convictions. That’s what the paper told us in a piece about protests in France over President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to raise the age for retirement benefits from 62 to 64.

“Mr. Macron’s decision to raise the legal age of retirement was based on his conviction that the pension system was unsustainable and that changing the program, with its generous benefits, was essential to France’s economic health [emphasis added].”

It’s good that the NYT could tell us Macron’s decision was based on his convictions and not say, a desire not to increase taxes on rich people to help cover the cost of the retirement system or even on working-age people. The employment rate among prime age workers (ages 25 to 54) is actually higher in France than in the U.S., so there is little reason to believe that a modest increase in taxes would lead them to stop working.

It is worth noting workers in France, unlike many workers in the U.S., actually are seeing increases in life expectancy. This means that even with this increase in the retirement age, workers retiring in future decades may still get to enjoy longer retirements than their parents.

I’m impressed. Most reporters might just know what politicians say and do, but New York Times reporters can apparently know their convictions. That’s what the paper told us in a piece about protests in France over President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to raise the age for retirement benefits from 62 to 64.

“Mr. Macron’s decision to raise the legal age of retirement was based on his conviction that the pension system was unsustainable and that changing the program, with its generous benefits, was essential to France’s economic health [emphasis added].”

It’s good that the NYT could tell us Macron’s decision was based on his convictions and not say, a desire not to increase taxes on rich people to help cover the cost of the retirement system or even on working-age people. The employment rate among prime age workers (ages 25 to 54) is actually higher in France than in the U.S., so there is little reason to believe that a modest increase in taxes would lead them to stop working.

It is worth noting workers in France, unlike many workers in the U.S., actually are seeing increases in life expectancy. This means that even with this increase in the retirement age, workers retiring in future decades may still get to enjoy longer retirements than their parents.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• BudgetBudget and National DebtHealth and Social ProgramsLos Programas Sociales y de SaludHealthcareUnited StatesEE. UU.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

• Economic GrowthEl DesarolloUnited StatesEE. UU.WorkersSector del trabajo

Last week, David Brooks had a column that was quite literally a celebration of American capitalism. He makes a number of points showing the U.S. doing better than other wealthy countries over the last three decades. While his numbers are not exactly wrong, they are somewhat misleading. (I see Paul Krugman beat me to the punch, so I’ll try not to be completely redundant.)

Brooks points to the faster GDP growth in the United States than in other wealthy countries. As Krugman notes, much of this gap is due to the fact that they have older populations; the differences are much smaller if we look at GDP per working-age person.

However, a big part of the story is also that they have opted to take much of the benefit of productivity growth in the form of more leisure time. In France, the length of the average work year was reduced by 9.1 percent between 1990 and 2021. In Germany, the decline was 13.8 percent. In Japan, average hours fell by 20.9 percent. In the United States, the length of the average work year fell by just 2.3 percent. On this score, there is not much to brag about here.

Brooks also cites data showing that the U.S. has seen more rapid productivity growth than other rich countries over the last three decades. This is true (austerity, which is more widely practiced in the EU than in the U.S., is a great way to kill growth), but it is worth mentioning some complicating factors in these comparisons.

For example, more than one-sixth of our GDP goes to health care. As Krugman points out, life expectancy in the United States has been stagnating and, in fact, declining for the poorer half of the population. That suggests that the share of our output that has gone into health care hasn’t done us too much good. (It’s true the decline might have been larger if not for the increased spending, but I’m not sure we want to brag much that our system is great because it slowed the decline in life expectancy.)

There are other things that get counted in GDP, and therefore productivity, that are of questionable value. For example, the money devoted to preventing school shootings (e.g. stronger doors, security alarms, school security guards, and grief counselors after the fact) all add to GDP and productivity growth. In a context where we have school shootings, these might be worthwhile expenditures, but most people would probably agree that we were better off in 1990 when we didn’t have to spend this money and school shootings were a rarity.

The other point about productivity growth is that we are still living in a slowdown world. In the years from 1947 to 1973, annual productivity growth averaged 2.8 percent. Since 1990 it has averaged 1.9 percent. That isn’t horrible, but it is markedly slower than the Golden Age growth. It is also worth noting that much of this growth was due to the Internet boom from 1995 to 2005 when growth averaged 3.0 percent annually. In the years before and after this period, productivity growth averaged just over 1.0 percent.

As Krugman points out, the benefits of the growth we have seen went disproportionately to those at the top. The median wage grew by 18.9 percent from 1990 to 2022, an average of just over 0.5 percent annually. It’s also worth noting that almost all of this growth took place in the tight labor markets of the late 1990s and from 2015 until the pandemic.

Finally, Brooks has the U.S. share of world GDP being unchanged in the years since 1990. This is likely because he was using GDP measured at exchange rate values. This is a rather arbitrary measure that varies hugely as currencies fluctuate. The U.S. GDP by this measure will also be inflated insofar as countries “manipulate” their currency by buying up dollar-based assets with their reserves.

A more standard measure of economic output for purposes of international comparisons is purchasing power parity GDP. This measure applies a common set of prices to all goods and services produced in each country. This measure tells a very different story.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

As can be seen, the U.S. share has declined from 21.5 percent in 1990 to a projected 15.4 percent this year. I have also included the I.M.F. projections which show a further decline to 14.5 percent by 2028. Perhaps more importantly, China’s share has risen dramatically.[1] It crossed the U.S. share in 2014 and is projected to be 19.3 percent this year. It is projected to rise further to 20.1 percent in 2028, not far below the U.S. share in 1990. In short, China is now the top dog in terms of contribution to work GDP by a fairly large margin.

There are still plenty of good things that can be said about the U.S. economy, but there is perhaps less to celebrate than David Brooks would have us believe.

[1] I’ve included Hong Kong and Macao’s data in the calculation of China’s GDP share.

Last week, David Brooks had a column that was quite literally a celebration of American capitalism. He makes a number of points showing the U.S. doing better than other wealthy countries over the last three decades. While his numbers are not exactly wrong, they are somewhat misleading. (I see Paul Krugman beat me to the punch, so I’ll try not to be completely redundant.)

Brooks points to the faster GDP growth in the United States than in other wealthy countries. As Krugman notes, much of this gap is due to the fact that they have older populations; the differences are much smaller if we look at GDP per working-age person.

However, a big part of the story is also that they have opted to take much of the benefit of productivity growth in the form of more leisure time. In France, the length of the average work year was reduced by 9.1 percent between 1990 and 2021. In Germany, the decline was 13.8 percent. In Japan, average hours fell by 20.9 percent. In the United States, the length of the average work year fell by just 2.3 percent. On this score, there is not much to brag about here.

Brooks also cites data showing that the U.S. has seen more rapid productivity growth than other rich countries over the last three decades. This is true (austerity, which is more widely practiced in the EU than in the U.S., is a great way to kill growth), but it is worth mentioning some complicating factors in these comparisons.

For example, more than one-sixth of our GDP goes to health care. As Krugman points out, life expectancy in the United States has been stagnating and, in fact, declining for the poorer half of the population. That suggests that the share of our output that has gone into health care hasn’t done us too much good. (It’s true the decline might have been larger if not for the increased spending, but I’m not sure we want to brag much that our system is great because it slowed the decline in life expectancy.)

There are other things that get counted in GDP, and therefore productivity, that are of questionable value. For example, the money devoted to preventing school shootings (e.g. stronger doors, security alarms, school security guards, and grief counselors after the fact) all add to GDP and productivity growth. In a context where we have school shootings, these might be worthwhile expenditures, but most people would probably agree that we were better off in 1990 when we didn’t have to spend this money and school shootings were a rarity.

The other point about productivity growth is that we are still living in a slowdown world. In the years from 1947 to 1973, annual productivity growth averaged 2.8 percent. Since 1990 it has averaged 1.9 percent. That isn’t horrible, but it is markedly slower than the Golden Age growth. It is also worth noting that much of this growth was due to the Internet boom from 1995 to 2005 when growth averaged 3.0 percent annually. In the years before and after this period, productivity growth averaged just over 1.0 percent.

As Krugman points out, the benefits of the growth we have seen went disproportionately to those at the top. The median wage grew by 18.9 percent from 1990 to 2022, an average of just over 0.5 percent annually. It’s also worth noting that almost all of this growth took place in the tight labor markets of the late 1990s and from 2015 until the pandemic.

Finally, Brooks has the U.S. share of world GDP being unchanged in the years since 1990. This is likely because he was using GDP measured at exchange rate values. This is a rather arbitrary measure that varies hugely as currencies fluctuate. The U.S. GDP by this measure will also be inflated insofar as countries “manipulate” their currency by buying up dollar-based assets with their reserves.

A more standard measure of economic output for purposes of international comparisons is purchasing power parity GDP. This measure applies a common set of prices to all goods and services produced in each country. This measure tells a very different story.

Source: International Monetary Fund.

As can be seen, the U.S. share has declined from 21.5 percent in 1990 to a projected 15.4 percent this year. I have also included the I.M.F. projections which show a further decline to 14.5 percent by 2028. Perhaps more importantly, China’s share has risen dramatically.[1] It crossed the U.S. share in 2014 and is projected to be 19.3 percent this year. It is projected to rise further to 20.1 percent in 2028, not far below the U.S. share in 1990. In short, China is now the top dog in terms of contribution to work GDP by a fairly large margin.

There are still plenty of good things that can be said about the U.S. economy, but there is perhaps less to celebrate than David Brooks would have us believe.

[1] I’ve included Hong Kong and Macao’s data in the calculation of China’s GDP share.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión