Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That might have been a better headline for a NYT piece on the Trans-Pacific Partnership. As the piece points out, the provisions on labor rights in Vietnam and currency interventions by governments, which have been widely touted by the Obama administration, are not actually enforceable under the terms of the TPP. There are other much less well-defined mechanisms. On the other hand, if Pfizer wants to argue that Australia is not respecting its patent rights or George Lucas wants to complain that Malaysia is not honoring his copyrights on Star Wars, there is recourse through the Investor-State Dispute Settlement mechanism.

That might have been a better headline for a NYT piece on the Trans-Pacific Partnership. As the piece points out, the provisions on labor rights in Vietnam and currency interventions by governments, which have been widely touted by the Obama administration, are not actually enforceable under the terms of the TPP. There are other much less well-defined mechanisms. On the other hand, if Pfizer wants to argue that Australia is not respecting its patent rights or George Lucas wants to complain that Malaysia is not honoring his copyrights on Star Wars, there is recourse through the Investor-State Dispute Settlement mechanism.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post got recent history badly wrong in the third paragraph of its lead front page article when it told readers:

“Three years ago, GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney and Ryan, his running mate, faced withering Democratic attacks after endorsing dramatic overhauls of Medicare and Social Security that proved unpopular.”

Actually, Romney did not endorse an overhaul of Social Security in his 2012 campaign, although Ryan has long been on record as favoring privatization. Presumably, they chose not to raise the issue in the campaign since they knew it would be highly unpopular.

The piece also notes Governor Chris Christie’s characterization of himself as a “truth-teller” on Social Security and then reports on his plan to save the system money by means-testing benefits starting at $80,000 and eliminating them entirely for people with incomes over $200,000. The truth is that this cut would only reduce spending by 1.0-1.5 percent. Furthermore, it would effectively increase the marginal tax rate for people in this $80,000-$200,000 range by more than 20 percentage points.

Correction:

While Romney did not call for privatizing Social Security, he did propose raising the normal retirement age by two years to 69. He also proposed reducing benefits for middle and upper income workers from their currently scheduled levels.

The Washington Post got recent history badly wrong in the third paragraph of its lead front page article when it told readers:

“Three years ago, GOP presidential nominee Mitt Romney and Ryan, his running mate, faced withering Democratic attacks after endorsing dramatic overhauls of Medicare and Social Security that proved unpopular.”

Actually, Romney did not endorse an overhaul of Social Security in his 2012 campaign, although Ryan has long been on record as favoring privatization. Presumably, they chose not to raise the issue in the campaign since they knew it would be highly unpopular.

The piece also notes Governor Chris Christie’s characterization of himself as a “truth-teller” on Social Security and then reports on his plan to save the system money by means-testing benefits starting at $80,000 and eliminating them entirely for people with incomes over $200,000. The truth is that this cut would only reduce spending by 1.0-1.5 percent. Furthermore, it would effectively increase the marginal tax rate for people in this $80,000-$200,000 range by more than 20 percentage points.

Correction:

While Romney did not call for privatizing Social Security, he did propose raising the normal retirement age by two years to 69. He also proposed reducing benefits for middle and upper income workers from their currently scheduled levels.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post decided to correct the positive image of Denmark that Senator Bernie Sanders and others have been giving it in recent months. It ran a piece telling readers:

“Why Denmark isn’t the Utopian fantasy Bernie Sanders describes.”

The piece is centered on an interview with Michael Booth, a food and travel writer who has spent a considerable period of time in the Scandinavian countries.

Much of the piece is focuses on the alleged economic problems of Denmark and the other Scandinavian countries. At one point the interviewer (Ana Swanson) asks:

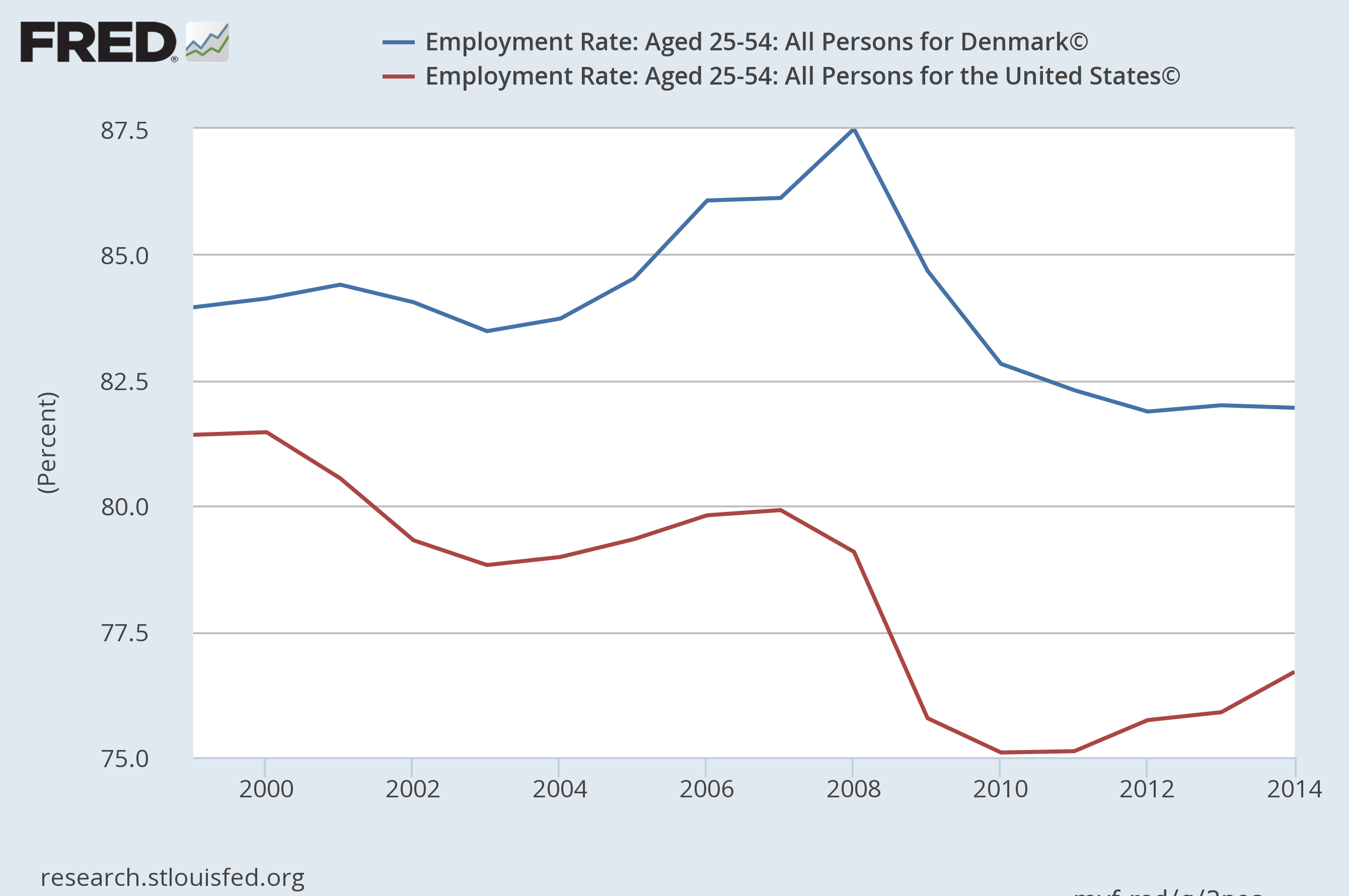

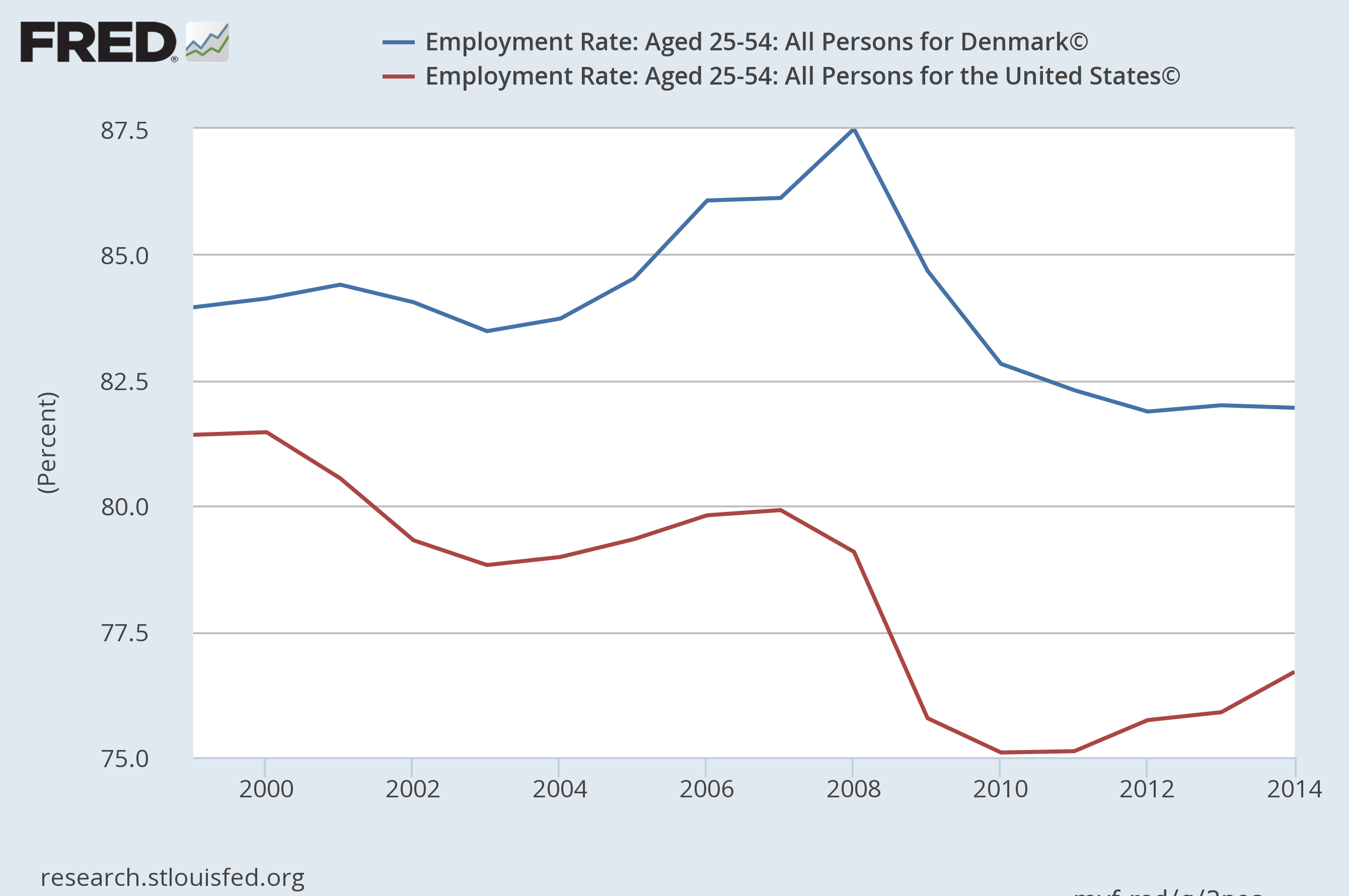

“Danes are experiencing a rising debt level, and a lower proportion of people working. Are these worrying signs for its economy or the country’s model?”

While Denmark’s employment rate has been declining, it is still far higher than the employment rate in the United States. The employment rate for prime age workers (ages 25–54) is still more than 5 full percentage points higher than in the United States. If the rate of decline since the 2001 peak continues, it will fall below the current U.S. level in roughly 24 years. (The U.S. rate also fell over this period.) If we take the broader 16–64 age group then the gap falls slightly to 4.7 percentage points.

As far as having an unsustainable debt level, Swanson seems somewhat confused. According to the I.M.F., Denmark’s net debt as a percent of its GDP will be 6.3 percent at the end of this year. Sweden has a negative net debt, meaning the government owns more financial assets than the amount of debt it has outstanding. In Norway’s case, because of its huge oil assets, the proceeds of which it has largely saved, the government wealth to GDP ratio is almost 270 percent. This would be equivalent to having a public investment fund of more than $40 trillion in the United States.

Some of the other assertions in the piece are either misleading or inaccurate. For example, Booth is quoted as saying:

“Meanwhile, though it is true that these are the most gender-equal societies in the world, they also record the highest rates of violence towards women — only part of which can be explained by high levels of reporting of crime.”

Actually, Danish women are far less likely to be murdered by their husbands or boyfriends than women in the United States. Its murder rate is 1.1 per 100,000, compared to 5.5 per 100,000 in the United States.

Later Booth is quoted as saying:

“In Denmark, the quality of the free education and health care is substandard: They are way down on the PISA [Programme for International Student Assessment] educational rankings, have the lowest life expectancy in the region, and the highest rates of death from cancer. And there is broad consensus that the economic model of a public sector and welfare state on this scale is unsustainable.”

While Denmark is not among the leaders on either PISA scores or life expectancy, on both measures it is well ahead of the United States. And the “broad consensus that the economic model…is unsustainable” exists only in Booth’s head.

Booth is also apparently confused about tax rates around the world. He tells readers:

“Denmark has the highest direct and indirect taxes in the world, and you don’t need to be a high earner to make it into the top tax bracket of 56% (to which you must add 25% value-added tax, the highest energy taxes in the world, car import duty of 180%, and so on).”

Actually France has a top marginal tax rate of 75 percent. The U.S. rate was 90 percent during the Eisenhower administration.

Booth apparently is confused about Denmark’s public spending. He tells readers:

“How the money is spent is kept deliberately opaque by the authorities.”

Actually, it is not difficult to find a great deal of information about Denmark’s money is spent. Much of it can be gotten from the OECD’s website.

So we get that Mr. Booth doesn’t like Denmark. He tells readers that the food and weather are awful. That may be true, but his analysis of other aspects of Danish society doesn’t fit with the data.

The Washington Post decided to correct the positive image of Denmark that Senator Bernie Sanders and others have been giving it in recent months. It ran a piece telling readers:

“Why Denmark isn’t the Utopian fantasy Bernie Sanders describes.”

The piece is centered on an interview with Michael Booth, a food and travel writer who has spent a considerable period of time in the Scandinavian countries.

Much of the piece is focuses on the alleged economic problems of Denmark and the other Scandinavian countries. At one point the interviewer (Ana Swanson) asks:

“Danes are experiencing a rising debt level, and a lower proportion of people working. Are these worrying signs for its economy or the country’s model?”

While Denmark’s employment rate has been declining, it is still far higher than the employment rate in the United States. The employment rate for prime age workers (ages 25–54) is still more than 5 full percentage points higher than in the United States. If the rate of decline since the 2001 peak continues, it will fall below the current U.S. level in roughly 24 years. (The U.S. rate also fell over this period.) If we take the broader 16–64 age group then the gap falls slightly to 4.7 percentage points.

As far as having an unsustainable debt level, Swanson seems somewhat confused. According to the I.M.F., Denmark’s net debt as a percent of its GDP will be 6.3 percent at the end of this year. Sweden has a negative net debt, meaning the government owns more financial assets than the amount of debt it has outstanding. In Norway’s case, because of its huge oil assets, the proceeds of which it has largely saved, the government wealth to GDP ratio is almost 270 percent. This would be equivalent to having a public investment fund of more than $40 trillion in the United States.

Some of the other assertions in the piece are either misleading or inaccurate. For example, Booth is quoted as saying:

“Meanwhile, though it is true that these are the most gender-equal societies in the world, they also record the highest rates of violence towards women — only part of which can be explained by high levels of reporting of crime.”

Actually, Danish women are far less likely to be murdered by their husbands or boyfriends than women in the United States. Its murder rate is 1.1 per 100,000, compared to 5.5 per 100,000 in the United States.

Later Booth is quoted as saying:

“In Denmark, the quality of the free education and health care is substandard: They are way down on the PISA [Programme for International Student Assessment] educational rankings, have the lowest life expectancy in the region, and the highest rates of death from cancer. And there is broad consensus that the economic model of a public sector and welfare state on this scale is unsustainable.”

While Denmark is not among the leaders on either PISA scores or life expectancy, on both measures it is well ahead of the United States. And the “broad consensus that the economic model…is unsustainable” exists only in Booth’s head.

Booth is also apparently confused about tax rates around the world. He tells readers:

“Denmark has the highest direct and indirect taxes in the world, and you don’t need to be a high earner to make it into the top tax bracket of 56% (to which you must add 25% value-added tax, the highest energy taxes in the world, car import duty of 180%, and so on).”

Actually France has a top marginal tax rate of 75 percent. The U.S. rate was 90 percent during the Eisenhower administration.

Booth apparently is confused about Denmark’s public spending. He tells readers:

“How the money is spent is kept deliberately opaque by the authorities.”

Actually, it is not difficult to find a great deal of information about Denmark’s money is spent. Much of it can be gotten from the OECD’s website.

So we get that Mr. Booth doesn’t like Denmark. He tells readers that the food and weather are awful. That may be true, but his analysis of other aspects of Danish society doesn’t fit with the data.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Austin Frakt had an interesting piece discussing people’s abilities to select the lowest cost health care plan to meet their needs. He cites a number of studies that indicate people often make mistakes. For example, they frequently will pay way too much for plans with low deductibles and they fail to switch drug plans, even when they would have clear savings. (These behaviors are not necessarily irrational. If people know that a high deductible will discourage them from getting necessary care, they may opt for a plan that removes this obstacle. Also, filling out forms can be an ordeal for many people. If a person has familiarized themselves with one company’s forms, they may not want to switch companies and have to deal with a new set of forms, even if it could save them money.)

Anyhow, there is an interesting implication of this discussion that is not explored in the piece. If we assume that insurers have some target profit rate, then they obtain this rate from the average profit they earn from their customers. If insurers can make a larger than average profit from people who make bad choices, for example by paying too much to reduce their deductible, then they can make a lower than average profit from people who can effectively navigate through the choices offered.

This means that presenting a range of choices is a good way to redistribute from the people who are not very good at analyzing choices to those who are. The latter group tends to do things like write about insurance systems and advise politicians on these issues. This could help explain the preference by our politicians for systems involving choice over more simple options, like universal Medicare.

Austin Frakt had an interesting piece discussing people’s abilities to select the lowest cost health care plan to meet their needs. He cites a number of studies that indicate people often make mistakes. For example, they frequently will pay way too much for plans with low deductibles and they fail to switch drug plans, even when they would have clear savings. (These behaviors are not necessarily irrational. If people know that a high deductible will discourage them from getting necessary care, they may opt for a plan that removes this obstacle. Also, filling out forms can be an ordeal for many people. If a person has familiarized themselves with one company’s forms, they may not want to switch companies and have to deal with a new set of forms, even if it could save them money.)

Anyhow, there is an interesting implication of this discussion that is not explored in the piece. If we assume that insurers have some target profit rate, then they obtain this rate from the average profit they earn from their customers. If insurers can make a larger than average profit from people who make bad choices, for example by paying too much to reduce their deductible, then they can make a lower than average profit from people who can effectively navigate through the choices offered.

This means that presenting a range of choices is a good way to redistribute from the people who are not very good at analyzing choices to those who are. The latter group tends to do things like write about insurance systems and advise politicians on these issues. This could help explain the preference by our politicians for systems involving choice over more simple options, like universal Medicare.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Hey, better late than never. It was good to see two columns reporting on new data indicating that the Current Population Survey (CPS), the main survey used to measure poverty rates, as well as employment and unemployment, seriously undercounts the number of poor people due to undercoverage in its sample. It’s an important point and deserves attention.

We thought so too, which is why John Schmitt was writing about the issue almost a decade ago for CEPR. Schmitt noticed a large gap between employment rates as shown in the CPS and the 2000 Census long-form. The latter was lower with the largest gap for the groups with the lowest coverage rate in the CPS. (Coverage rates in the Census are close to 99 percent due to extensive outreach efforts.) In the case of young African American men the gap was close to 8.0 percentage points.

Anyhow, this is an important issue and it is good to see it get some attention. Of course it would have been better if it got some attention a decade ago.

Hey, better late than never. It was good to see two columns reporting on new data indicating that the Current Population Survey (CPS), the main survey used to measure poverty rates, as well as employment and unemployment, seriously undercounts the number of poor people due to undercoverage in its sample. It’s an important point and deserves attention.

We thought so too, which is why John Schmitt was writing about the issue almost a decade ago for CEPR. Schmitt noticed a large gap between employment rates as shown in the CPS and the 2000 Census long-form. The latter was lower with the largest gap for the groups with the lowest coverage rate in the CPS. (Coverage rates in the Census are close to 99 percent due to extensive outreach efforts.) In the case of young African American men the gap was close to 8.0 percentage points.

Anyhow, this is an important issue and it is good to see it get some attention. Of course it would have been better if it got some attention a decade ago.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

That is sort of what the Post reported. It told readers that:

“One of the largest federal programs that provides cash benefits to disabled workers overpaid $11 billion during the past nine years to people who returned to work and made too much money, a new study says.”

The Post article never bothered to tell readers that the program paid out roughly $1.1 trillion in benefits over this period, making the overpayment equal to 1.0 percent of benefits. It also would have been worth noting that the study by the Government Accountability Office found that most of this money is repaid, so that the government ends up losing substantially less than 0.5 percent of its spending on the disability program due to overpayments.

That is sort of what the Post reported. It told readers that:

“One of the largest federal programs that provides cash benefits to disabled workers overpaid $11 billion during the past nine years to people who returned to work and made too much money, a new study says.”

The Post article never bothered to tell readers that the program paid out roughly $1.1 trillion in benefits over this period, making the overpayment equal to 1.0 percent of benefits. It also would have been worth noting that the study by the Government Accountability Office found that most of this money is repaid, so that the government ends up losing substantially less than 0.5 percent of its spending on the disability program due to overpayments.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión