Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post, which has in the past expressed outrage over items like auto workers getting paid $28 an hour and people receiving disability benefits, is again pursuing its drive for higher unemployment. The context is an editorial denouncing former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s “pander” to middle class voters.

The specific issue is Clinton’s promise to increase government spending in various areas while ruling out a tax increase on families earning less than $250,000 a year. The Post tells readers that this promise will be impossible to keep:

“To the contrary, if the U.S. government is to do all those things and still reduce its long-term debt to a more manageable share of the total economy, middle- and upper-middle-class Americans are going to have to contribute more, not less.”

While the Post does have a good point on a pledge that sets promises to protect people earning more than 97 percent of the public from any tax increases (the $250,000 threshold), the idea that the current level of the debt is unmanageable has as much basis in reality as creationism. The interest rate on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds is just 2.2 percent. This is three full percentage points below the rates we saw in the late 1990s when the government was running budget surpluses. The current interest burden of the debt, net of payments from the Federal Reserve Board, is well under 1.0 percent of GDP. This compares to a burden of more than 3.0 percent of GDP in the early 1990s.

In other words, the Post has zero, nothing, nada, to support its contention that the current level of the debt is somehow unmanageable. This claim deserves to be derided for the sort of flat earth economics it is.

And, it needs to be pointed out that cutting the budget (or raising taxes) in a context where the economy is below full employment means reducing demand. This means reducing employment and increasing unemployment, especially in a context where there is no plausible story that interest rates will decline enough to induce an offsetting increase in demand.

So once again we see the Post pushing a policy with the predictable effect of hurting workers. It wants lower deficits and debt which will mean higher unemployment and lower wages. And, it is upset that Hillary Clinton doesn’t seem to share its agenda.

The Washington Post, which has in the past expressed outrage over items like auto workers getting paid $28 an hour and people receiving disability benefits, is again pursuing its drive for higher unemployment. The context is an editorial denouncing former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s “pander” to middle class voters.

The specific issue is Clinton’s promise to increase government spending in various areas while ruling out a tax increase on families earning less than $250,000 a year. The Post tells readers that this promise will be impossible to keep:

“To the contrary, if the U.S. government is to do all those things and still reduce its long-term debt to a more manageable share of the total economy, middle- and upper-middle-class Americans are going to have to contribute more, not less.”

While the Post does have a good point on a pledge that sets promises to protect people earning more than 97 percent of the public from any tax increases (the $250,000 threshold), the idea that the current level of the debt is unmanageable has as much basis in reality as creationism. The interest rate on 10-year U.S. Treasury bonds is just 2.2 percent. This is three full percentage points below the rates we saw in the late 1990s when the government was running budget surpluses. The current interest burden of the debt, net of payments from the Federal Reserve Board, is well under 1.0 percent of GDP. This compares to a burden of more than 3.0 percent of GDP in the early 1990s.

In other words, the Post has zero, nothing, nada, to support its contention that the current level of the debt is somehow unmanageable. This claim deserves to be derided for the sort of flat earth economics it is.

And, it needs to be pointed out that cutting the budget (or raising taxes) in a context where the economy is below full employment means reducing demand. This means reducing employment and increasing unemployment, especially in a context where there is no plausible story that interest rates will decline enough to induce an offsetting increase in demand.

So once again we see the Post pushing a policy with the predictable effect of hurting workers. It wants lower deficits and debt which will mean higher unemployment and lower wages. And, it is upset that Hillary Clinton doesn’t seem to share its agenda.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Steven Pearlstein has some useful ideas for limiting the rise in college costs, but he leaves an obvious item off the list. How about a hard cap on the pay of university presidents and other high level university employees?

The president of the United States gets $400,000 a year. That seems like a reasonable target. (This would be a hard cap, including all bonuses, deferred comp, etc. There is no reason to waste time with a cap that can be easily evaded.)

This would not be an interference with the market determination of pay. The deal would be that this cap would apply at public colleges and universities and also private schools that get tax-exempt status. If a school doesn’t want to get money from the government, either in direct payments or tax subsidies, it would be free to pay its top management whatever it wanted.

Of course schools would scream bloody murder since many now give their presidents compensation packages that are three or four times this amount. But, life is tough. Just as U.S. manufacturing workers have had to adjust to a world where they compete with workers in the developing world earning $1 an hour, or less, university presidents may have to adjust to a world in which taxpayers will not subsidize their pay without limit.

While some of the current crop of presidents may take their deferred compensation and walk, there are many talented and hardworking people who would gladly take a job that pays ten times what the median worker makes in a year. Besides, since we keep hearing cries from the Washington Post crowd about the need to tighten our belts, what could be a better place to start?

Steven Pearlstein has some useful ideas for limiting the rise in college costs, but he leaves an obvious item off the list. How about a hard cap on the pay of university presidents and other high level university employees?

The president of the United States gets $400,000 a year. That seems like a reasonable target. (This would be a hard cap, including all bonuses, deferred comp, etc. There is no reason to waste time with a cap that can be easily evaded.)

This would not be an interference with the market determination of pay. The deal would be that this cap would apply at public colleges and universities and also private schools that get tax-exempt status. If a school doesn’t want to get money from the government, either in direct payments or tax subsidies, it would be free to pay its top management whatever it wanted.

Of course schools would scream bloody murder since many now give their presidents compensation packages that are three or four times this amount. But, life is tough. Just as U.S. manufacturing workers have had to adjust to a world where they compete with workers in the developing world earning $1 an hour, or less, university presidents may have to adjust to a world in which taxpayers will not subsidize their pay without limit.

While some of the current crop of presidents may take their deferred compensation and walk, there are many talented and hardworking people who would gladly take a job that pays ten times what the median worker makes in a year. Besides, since we keep hearing cries from the Washington Post crowd about the need to tighten our belts, what could be a better place to start?

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The Washington Post had an article on a new report from the Government Accountability Office which noted that most clinical trials don’t report differences in outcome by gender. This could be another advantage of publicly funded clinical trials. The government could make a condition of financing that all the baseline characteristics of the participants in trials (e.g. gender, age, weight, etc.) be publicly disclosed along with the outcomes. This would allow other researchers and doctors to better determine which drugs might be best for their patients.

Of course, the other major advantage of having the government pay for the trials (after buying up all rights to the drugs) is that successful drugs would be immediately available at generic prices. It would not be necessary for hand wringing over paying tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars for drugs like Sovaldi or the new generation of cancer drugs coming on the market. It also wouldn’t then be necessary for the Obama administration to send its trade negotiators overseas to beat up our trading partners demanding stronger and longer patent and related protections for prescription drugs.

The Washington Post had an article on a new report from the Government Accountability Office which noted that most clinical trials don’t report differences in outcome by gender. This could be another advantage of publicly funded clinical trials. The government could make a condition of financing that all the baseline characteristics of the participants in trials (e.g. gender, age, weight, etc.) be publicly disclosed along with the outcomes. This would allow other researchers and doctors to better determine which drugs might be best for their patients.

Of course, the other major advantage of having the government pay for the trials (after buying up all rights to the drugs) is that successful drugs would be immediately available at generic prices. It would not be necessary for hand wringing over paying tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars for drugs like Sovaldi or the new generation of cancer drugs coming on the market. It also wouldn’t then be necessary for the Obama administration to send its trade negotiators overseas to beat up our trading partners demanding stronger and longer patent and related protections for prescription drugs.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

I’m a big fan of mass transit, bikes, and walking, but bad numbers are not the way to get people out of their cars. Someone came up with the statistic that the rate of traffic fatalties is 1.07 deaths per million vehicle miles traveled. Then, the NYT, ABC, NBC, Bloomberg, and AP all picked up this number.

Think about that one for a moment. The average car is driven roughly 10,000 miles a year. If you have 20 friends who are regular drivers, these news outlets want you to believe that one will be killed in a car accident every five years on average. Sound high?

Well, the correct number is 1.07 fatalities per 100 million miles according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, so they were off by a factor of 100. So be careful driving this holiday weekend, but the risks are not quite as great as some folks are saying.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for calling this one to my attention.

I’m a big fan of mass transit, bikes, and walking, but bad numbers are not the way to get people out of their cars. Someone came up with the statistic that the rate of traffic fatalties is 1.07 deaths per million vehicle miles traveled. Then, the NYT, ABC, NBC, Bloomberg, and AP all picked up this number.

Think about that one for a moment. The average car is driven roughly 10,000 miles a year. If you have 20 friends who are regular drivers, these news outlets want you to believe that one will be killed in a car accident every five years on average. Sound high?

Well, the correct number is 1.07 fatalities per 100 million miles according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, so they were off by a factor of 100. So be careful driving this holiday weekend, but the risks are not quite as great as some folks are saying.

Thanks to Robert Salzberg for calling this one to my attention.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

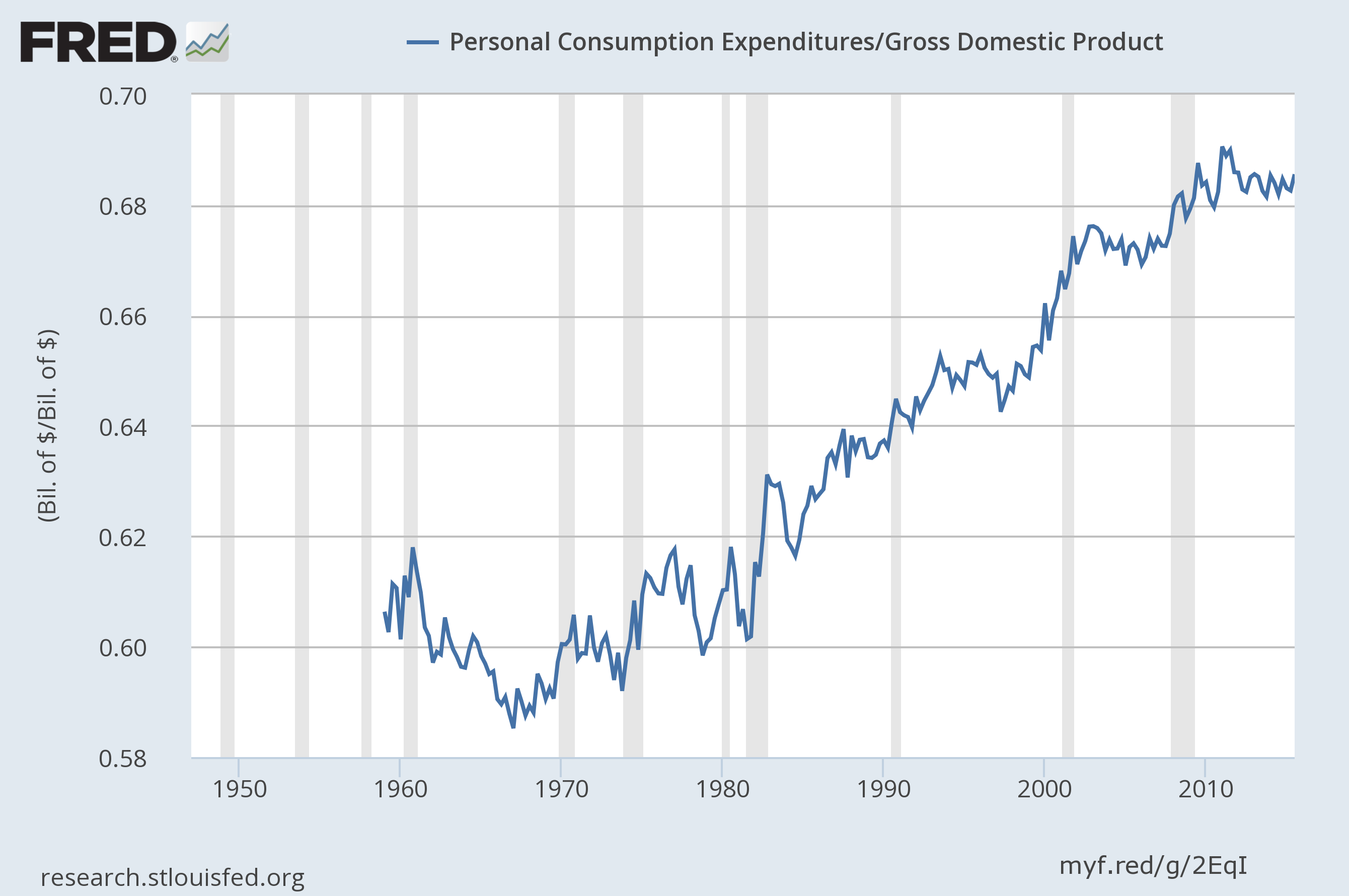

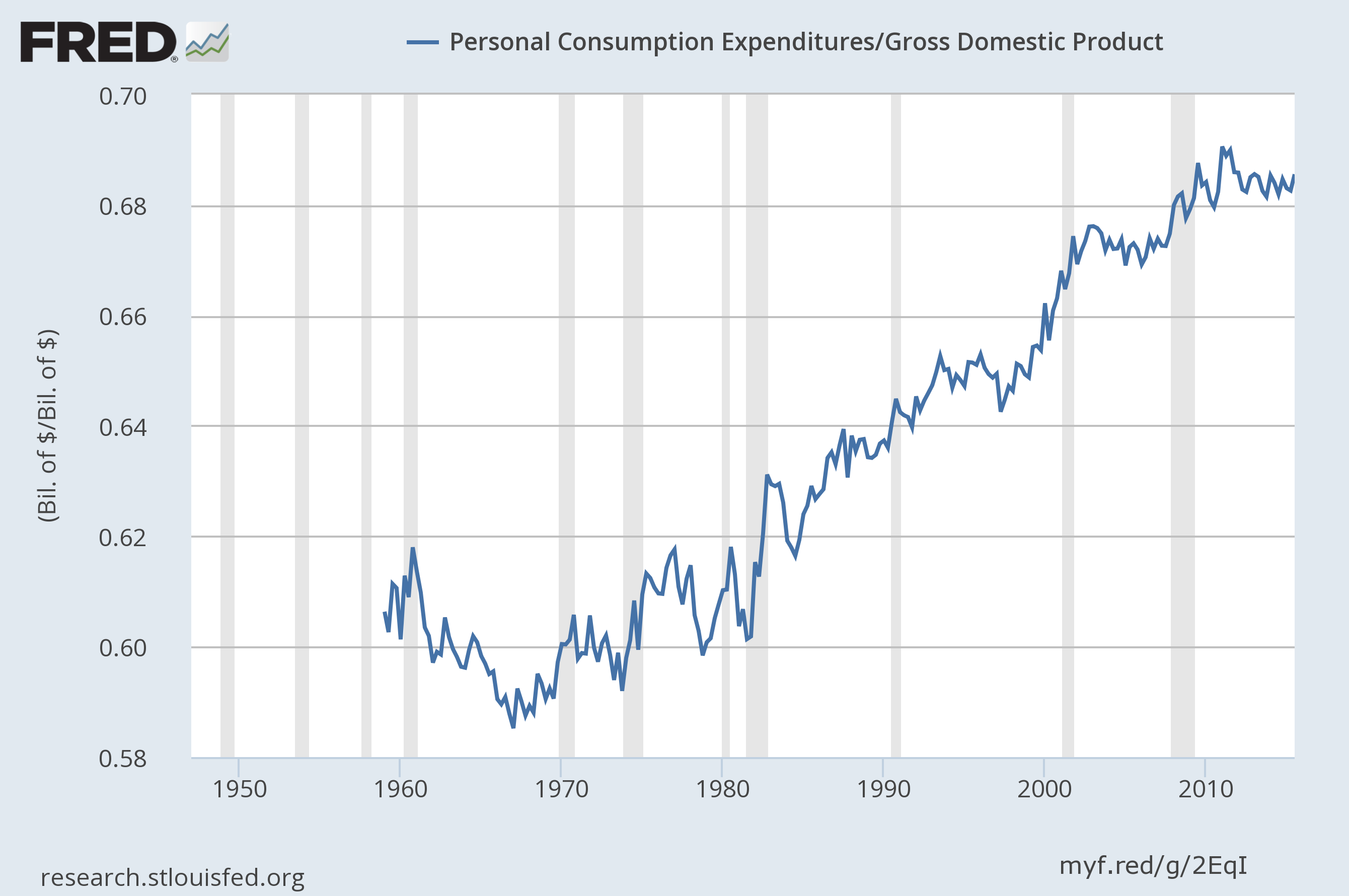

There is an ongoing myth about the downturn and the weak recovery that consumers unwillingness to spend has been a major factor holding back the recovery. An article in the Washington Post business section headlined, “heading into the holidays the retail industry faces a cautious consumer,” draws on this myth. The reality is that consumers have not been especially reluctant to spend in the downturn or the recovery as can be easily seen in this graph showing consumption as a share of GDP.

As can be seen, consumption is actually higher relative to GDP than it was before the downturn. It even higher relative to GDP than when the wealth created by the stock bubble lead to a boom in the late 1990s. The only time consumption was notably higher relative to GDP was in 2011 and 2012 when the payroll tax holiday on 2 percentage points of the Social Security tax temporarily boosted people’s disposable income relative to GDP.

(Those who see an upward trend need to think more carefully about what is being shown. Consumption can only continually rise as a share of GDP if investment and government spending continually fall and/or the trade deficit expands continually relative to the size of the economy. Standard models do not predict either event and both would be quite strange if true. It is also worth noting that the consumption share of GDP fell sharply in the 1960s due to the growth of investment and government spending.)

The weak consumption story is one of the myths that makes the housing bubble far more complicated that it actually is. The basic story is that housing construction, and the consumption driven by housing bubble generated equity, were driving the economy before the bubble burst in 2006–2008. When the bubble burst, the over-construction of the bubble years led to a huge falloff in construction and a temporary drop in consumption.

There was no component of demand that could easily fill this gap, which was on the order of six percentage points of GDP (@$1.1 trillion annually in today’s economy.) The stimulus went part of the way, but it was too small and faded back to near zero by 2011.

The problem of the continuing weakness of the economy is that we still have nothing to fill this demand gap. Housing has come back to near normal levels, but not the boom levels of the bubble years. If anything, consumption is unusually high, driven by house and stock prices that are above trend, even if not necessarily at bubble levels.

The one sure way to close the demand gap is to reduce the trade deficit, most obviously by getting down the value of the dollar. Unfortunately, the powers that be in Washington don’t talk about currency values, hence there are no provisions on currency in the Trans-Pacific Partnership. (There is an unenforceable side agreement.) We could try to get to full employment with shorter work weeks and years, through measures such as work sharing, paid family leave, and paid vacations, but this route is also largely off the agenda.

Anyhow, we don’t have cautious consumers and we don’t have any mysteries about the economy’s ongoing weakness. We just have a lot of confusion generated by the media in discussing the topic.

There is an ongoing myth about the downturn and the weak recovery that consumers unwillingness to spend has been a major factor holding back the recovery. An article in the Washington Post business section headlined, “heading into the holidays the retail industry faces a cautious consumer,” draws on this myth. The reality is that consumers have not been especially reluctant to spend in the downturn or the recovery as can be easily seen in this graph showing consumption as a share of GDP.

As can be seen, consumption is actually higher relative to GDP than it was before the downturn. It even higher relative to GDP than when the wealth created by the stock bubble lead to a boom in the late 1990s. The only time consumption was notably higher relative to GDP was in 2011 and 2012 when the payroll tax holiday on 2 percentage points of the Social Security tax temporarily boosted people’s disposable income relative to GDP.

(Those who see an upward trend need to think more carefully about what is being shown. Consumption can only continually rise as a share of GDP if investment and government spending continually fall and/or the trade deficit expands continually relative to the size of the economy. Standard models do not predict either event and both would be quite strange if true. It is also worth noting that the consumption share of GDP fell sharply in the 1960s due to the growth of investment and government spending.)

The weak consumption story is one of the myths that makes the housing bubble far more complicated that it actually is. The basic story is that housing construction, and the consumption driven by housing bubble generated equity, were driving the economy before the bubble burst in 2006–2008. When the bubble burst, the over-construction of the bubble years led to a huge falloff in construction and a temporary drop in consumption.

There was no component of demand that could easily fill this gap, which was on the order of six percentage points of GDP (@$1.1 trillion annually in today’s economy.) The stimulus went part of the way, but it was too small and faded back to near zero by 2011.

The problem of the continuing weakness of the economy is that we still have nothing to fill this demand gap. Housing has come back to near normal levels, but not the boom levels of the bubble years. If anything, consumption is unusually high, driven by house and stock prices that are above trend, even if not necessarily at bubble levels.

The one sure way to close the demand gap is to reduce the trade deficit, most obviously by getting down the value of the dollar. Unfortunately, the powers that be in Washington don’t talk about currency values, hence there are no provisions on currency in the Trans-Pacific Partnership. (There is an unenforceable side agreement.) We could try to get to full employment with shorter work weeks and years, through measures such as work sharing, paid family leave, and paid vacations, but this route is also largely off the agenda.

Anyhow, we don’t have cautious consumers and we don’t have any mysteries about the economy’s ongoing weakness. We just have a lot of confusion generated by the media in discussing the topic.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión