In a piece on the difficulty that many people are having in paying their rent, Morning Edition told listeners that rents have risen back to their levels of the housing bubble years. Actually rents didn’t rise in the housing bubble, rather they pretty much tracked the overall rate of inflation. The sharp divergence between house sale prices and rents was one of the reasons that people who pay attention to data were able to recognize the bubble.

In a piece on the difficulty that many people are having in paying their rent, Morning Edition told listeners that rents have risen back to their levels of the housing bubble years. Actually rents didn’t rise in the housing bubble, rather they pretty much tracked the overall rate of inflation. The sharp divergence between house sale prices and rents was one of the reasons that people who pay attention to data were able to recognize the bubble.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

It’s clear that Bernie Sanders has gotten many mainstream types upset. After all, he is raising issues about the distribution of wealth and income that they would prefer be kept in academic settings, certainly not pushed front and center in a presidential campaign.

In response, we are seeing endless shots at Sanders’ plans for financial reform, health care reform, and expanding Social Security. Many of these pieces raise perfectly reasonable questions, both about Sanders’ goals and his route for achieving them. But there are also many pieces that just shoot blindly. It seems the view of many in the media is that Sanders is a fringe candidate, so it’s not necessary to treat his positions with the same respect awarded the views of a Hillary Clinton or Marco Rubio.

The New Yorker is clearly in this attack mode. It ran a piece by Alexandra Schwartz asking, “Should Millennials Get Over Bernie Sanders?” You can guess the answer.

But the piece runs into serious problems getting there. It tells readers:

“[Sanders’] obsession with the banks and the bailout is itself phrased in weirdly retro terms, the stuff of an invitation to a 2008-election theme party. As my colleague Ben Wallace-Wells points out, we voters under thirty have come of political age during the economic recovery under President Obama. When I graduated from college, unemployment was close to ten per cent; it’s now at five. Sanders’s attention to socioeconomic justice is stirring and necessary, but when his campaign tweets that it’s “high time we stopped bailing out Wall Street and started repairing Main Street,” you have to wonder why his youngest supporters, so attuned to staleness in all things cultural, are letting him get away with political rhetoric that would have seemed old even in 2012.”

Those familiar with economic data know the labor market, which is the economy for the vast majority of the public, is very far from recovering from the recession. While the unemployment rate is reasonably low, this is largely because millions of workers have dropped out of the workforce.

And, contrary to what is often asserted, these are not retiring baby boomers or people without the skills needed in a modern economy. The employment rate of prime age workers (ages 25–54) is still down by 3.0 percentage points from its pre-recession level. Furthermore, this drop is for workers at all levels of educational attainment. Employment rates are even down for workers with college and advanced degrees. Other measures of labor market strength, like the percentage of people involuntarily working part-time, the quit rate, and the duration of unemployment spells are all still at recession levels.

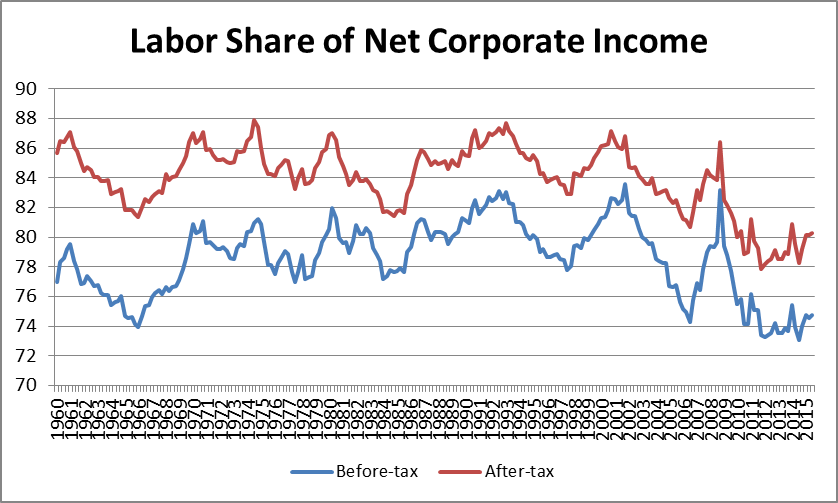

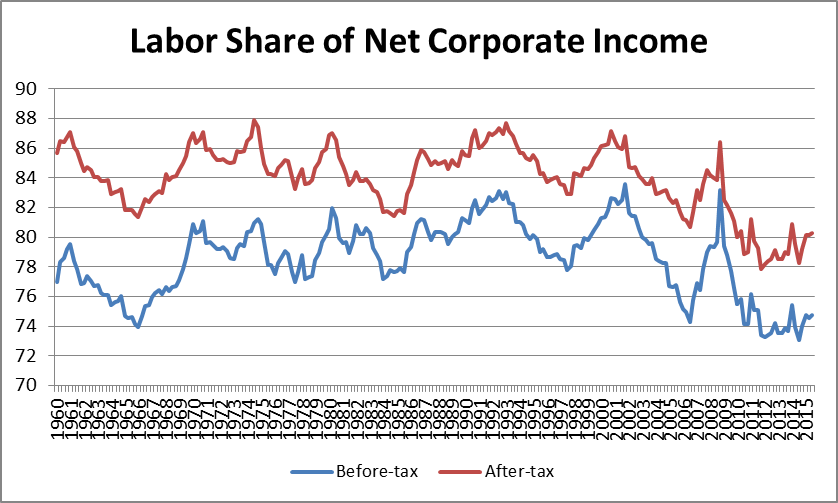

Furthermore, the huge shift from wages to profits that we saw in the downturn has not been reversed. As a result, wages are more than 6.0 percent lower than they would be if the labor share had not changed.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

If this stuff is hard for New Yorker editor types to understand, if workers lose 6.0 percent of their wages to profit it has the same impact on their living standards as if they faced a 6.0 percentage point increase in the payroll tax. Would the New Yorker think that today’s young people have anything to complain about if they had seen an increase in the payroll tax in 2009-2010 of 6.0 percentage points and which still remains in place today?

If the answer to that one is “yes,” then its editors should be able to understand why millennials in 2016 are unhappy about the state of the economy and why they might find a figure like Senator Sanders attractive.

It’s clear that Bernie Sanders has gotten many mainstream types upset. After all, he is raising issues about the distribution of wealth and income that they would prefer be kept in academic settings, certainly not pushed front and center in a presidential campaign.

In response, we are seeing endless shots at Sanders’ plans for financial reform, health care reform, and expanding Social Security. Many of these pieces raise perfectly reasonable questions, both about Sanders’ goals and his route for achieving them. But there are also many pieces that just shoot blindly. It seems the view of many in the media is that Sanders is a fringe candidate, so it’s not necessary to treat his positions with the same respect awarded the views of a Hillary Clinton or Marco Rubio.

The New Yorker is clearly in this attack mode. It ran a piece by Alexandra Schwartz asking, “Should Millennials Get Over Bernie Sanders?” You can guess the answer.

But the piece runs into serious problems getting there. It tells readers:

“[Sanders’] obsession with the banks and the bailout is itself phrased in weirdly retro terms, the stuff of an invitation to a 2008-election theme party. As my colleague Ben Wallace-Wells points out, we voters under thirty have come of political age during the economic recovery under President Obama. When I graduated from college, unemployment was close to ten per cent; it’s now at five. Sanders’s attention to socioeconomic justice is stirring and necessary, but when his campaign tweets that it’s “high time we stopped bailing out Wall Street and started repairing Main Street,” you have to wonder why his youngest supporters, so attuned to staleness in all things cultural, are letting him get away with political rhetoric that would have seemed old even in 2012.”

Those familiar with economic data know the labor market, which is the economy for the vast majority of the public, is very far from recovering from the recession. While the unemployment rate is reasonably low, this is largely because millions of workers have dropped out of the workforce.

And, contrary to what is often asserted, these are not retiring baby boomers or people without the skills needed in a modern economy. The employment rate of prime age workers (ages 25–54) is still down by 3.0 percentage points from its pre-recession level. Furthermore, this drop is for workers at all levels of educational attainment. Employment rates are even down for workers with college and advanced degrees. Other measures of labor market strength, like the percentage of people involuntarily working part-time, the quit rate, and the duration of unemployment spells are all still at recession levels.

Furthermore, the huge shift from wages to profits that we saw in the downturn has not been reversed. As a result, wages are more than 6.0 percent lower than they would be if the labor share had not changed.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

If this stuff is hard for New Yorker editor types to understand, if workers lose 6.0 percent of their wages to profit it has the same impact on their living standards as if they faced a 6.0 percentage point increase in the payroll tax. Would the New Yorker think that today’s young people have anything to complain about if they had seen an increase in the payroll tax in 2009-2010 of 6.0 percentage points and which still remains in place today?

If the answer to that one is “yes,” then its editors should be able to understand why millennials in 2016 are unhappy about the state of the economy and why they might find a figure like Senator Sanders attractive.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had a front page article on how bad debt is threatening world growth. The article focused on China, which it indicated could have as much as $6 trillion in bad debt.

It would have been worth mentioning that China’s government could easily cover the cost of bad debt and keep its economy moving forward. The government’s debt to GDP ratio is very low, its interest burden is less than 1.0 percent of GDP, and it is more worried about deflation than inflation.

In this context, there is no economic reason the government could not put up the money to clear up bad debts. The only obstacles would be political.

The NYT had a front page article on how bad debt is threatening world growth. The article focused on China, which it indicated could have as much as $6 trillion in bad debt.

It would have been worth mentioning that China’s government could easily cover the cost of bad debt and keep its economy moving forward. The government’s debt to GDP ratio is very low, its interest burden is less than 1.0 percent of GDP, and it is more worried about deflation than inflation.

In this context, there is no economic reason the government could not put up the money to clear up bad debts. The only obstacles would be political.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Eduardo Porter had a piece this morning about how a group of academics on the left and right came together around a common agenda. It is worth briefly commenting on two of the items on which the “left” made concessions.

The first is agreeing that Social Security benefits for “affluent Americans” should be reduced. There are three major problems with this policy. The first is that “affluent Americans” don’t get very much Social Security. While it is possible to raise lots of money by increasing taxes on the richest 1–2 percent of the population, the rich don’t get much more in Social Security than anyone else. This means that if we want to get any significant amount of money from reducing the benefits for the affluent we would have to reduce benefits for people that almost no one would consider affluent. Even if we went as low as $40,000 as the income cutoff for lowering benefits, we would still only save a very limited amount of money.

The second problem is that reducing benefits based on income is equivalent to a large tax increase. To get any substantial amount of money through this route we would need to reduce benefits at a rate of something like 20 cents per dollar of additional income. This is equivalent to increasing the marginal tax rate by 20 percentage points. As conservatives like to point out, this gives people a strong incentive to evade the tax by hiding income and discourages them from working.

Finally, people have worked for these benefits. We could also reduce the interest payments that the wealthy receive on government bonds they hold. After all, they don’t need as much interest as middle-income people. However no one would suggest going this route since the government contracted to pay a given interest rate.

Social Security involves a similar sort of commitment, although many on the right would like to deny this fact. The program is already structured to be highly progressive, the wealthy pay much more money into the program for every dollar they get back. There are many proposals from the left to make the program even more progressive by increasing the taxes paid by the wealthy. This would help to ensure the long-term solvency of the program while maintaining the level of benefits for all workers. There is a serious risk that cutting benefits for middle income seniors will be a first step in the opposite direction, undermining the public support for the program.

The other dubious position in this agenda is the strong endorsement for marriage. While there are enormous benefits from strong relationships, especially for children, the government is not a very good matchmaker. It is not obvious what the government can do to increase the likelihood that two compatible people will remain together in a healthy relationship.

There are plenty of unhealthy relationships, where one member is abusive of the other and often children. In these cases, it is not good to keep couples together and it would be foolish for the government to try.

As a matter of policy, we have to recognize that a large number of children will be raised by single parents. We need policy to ensure that these children are not penalized as a result of their parent’s marital status. Many proposals to promote marriage will at least indirectly have this effect.

Eduardo Porter had a piece this morning about how a group of academics on the left and right came together around a common agenda. It is worth briefly commenting on two of the items on which the “left” made concessions.

The first is agreeing that Social Security benefits for “affluent Americans” should be reduced. There are three major problems with this policy. The first is that “affluent Americans” don’t get very much Social Security. While it is possible to raise lots of money by increasing taxes on the richest 1–2 percent of the population, the rich don’t get much more in Social Security than anyone else. This means that if we want to get any significant amount of money from reducing the benefits for the affluent we would have to reduce benefits for people that almost no one would consider affluent. Even if we went as low as $40,000 as the income cutoff for lowering benefits, we would still only save a very limited amount of money.

The second problem is that reducing benefits based on income is equivalent to a large tax increase. To get any substantial amount of money through this route we would need to reduce benefits at a rate of something like 20 cents per dollar of additional income. This is equivalent to increasing the marginal tax rate by 20 percentage points. As conservatives like to point out, this gives people a strong incentive to evade the tax by hiding income and discourages them from working.

Finally, people have worked for these benefits. We could also reduce the interest payments that the wealthy receive on government bonds they hold. After all, they don’t need as much interest as middle-income people. However no one would suggest going this route since the government contracted to pay a given interest rate.

Social Security involves a similar sort of commitment, although many on the right would like to deny this fact. The program is already structured to be highly progressive, the wealthy pay much more money into the program for every dollar they get back. There are many proposals from the left to make the program even more progressive by increasing the taxes paid by the wealthy. This would help to ensure the long-term solvency of the program while maintaining the level of benefits for all workers. There is a serious risk that cutting benefits for middle income seniors will be a first step in the opposite direction, undermining the public support for the program.

The other dubious position in this agenda is the strong endorsement for marriage. While there are enormous benefits from strong relationships, especially for children, the government is not a very good matchmaker. It is not obvious what the government can do to increase the likelihood that two compatible people will remain together in a healthy relationship.

There are plenty of unhealthy relationships, where one member is abusive of the other and often children. In these cases, it is not good to keep couples together and it would be foolish for the government to try.

As a matter of policy, we have to recognize that a large number of children will be raised by single parents. We need policy to ensure that these children are not penalized as a result of their parent’s marital status. Many proposals to promote marriage will at least indirectly have this effect.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

The NYT had an article on different trade models that are being used to predict the impact of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). It reported on the projections from a model from the Peterson Institute which shows that the TPP would add 0.036 percentage points to the annual growth for the United States rate over the next 14 years. On the other hand, it reported the projections of a model from Tufts University which showed that the deal would lose economy 450,000 jobs (@0.3 percent of total employment) and slow growth.

It would have been helpful to add a bit of background to this dispute. The model from the Peterson Institute explicitly assumes that the trade deal cannot have an effect on the trade deficit and employment:

“The model assumes that the TPP will affect neither total employment nor the national savings (or equivalently trade balances) of countries.”

This was a conventional assumption in trade models prior to the Great Recession. The view was that if a trade deal led to a change in the trade deficit, currencies values would adjust so that the overall trade balance would not change. Furthermore, even if a rise in the trade deficit did lead to some fall in output and employment, this could be offset by fiscal and/or monetary policy. Therefore economists need not worry about trade’s impact on aggregate output and employment.

In the wake of the Great Recession many of the world’s most prominent economists (e.g. Larry Summers, Paul Krugman, Olivier Blanchard) no longer believe that the economy will automatically bounce back to full employment. They now accept the idea of “secular stagnation,” which means that economies can suffer from long periods of inadequate demand. If secular stagnation is a real problem, then there is no basis for assuming that the demand and jobs lost due to a larger trade deficit can be offset by other policies.

The NYT had an article on different trade models that are being used to predict the impact of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). It reported on the projections from a model from the Peterson Institute which shows that the TPP would add 0.036 percentage points to the annual growth for the United States rate over the next 14 years. On the other hand, it reported the projections of a model from Tufts University which showed that the deal would lose economy 450,000 jobs (@0.3 percent of total employment) and slow growth.

It would have been helpful to add a bit of background to this dispute. The model from the Peterson Institute explicitly assumes that the trade deal cannot have an effect on the trade deficit and employment:

“The model assumes that the TPP will affect neither total employment nor the national savings (or equivalently trade balances) of countries.”

This was a conventional assumption in trade models prior to the Great Recession. The view was that if a trade deal led to a change in the trade deficit, currencies values would adjust so that the overall trade balance would not change. Furthermore, even if a rise in the trade deficit did lead to some fall in output and employment, this could be offset by fiscal and/or monetary policy. Therefore economists need not worry about trade’s impact on aggregate output and employment.

In the wake of the Great Recession many of the world’s most prominent economists (e.g. Larry Summers, Paul Krugman, Olivier Blanchard) no longer believe that the economy will automatically bounce back to full employment. They now accept the idea of “secular stagnation,” which means that economies can suffer from long periods of inadequate demand. If secular stagnation is a real problem, then there is no basis for assuming that the demand and jobs lost due to a larger trade deficit can be offset by other policies.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Margot Sanger-Katz had a NYT Upshot column arguing that Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders plans to have Medicare negotiate drug prices ultimately won’t prove successful in lowering costs because Medicare can’t simply refuse to pay for a drug. There is much truth to this argument, but it is worth working through the dynamics a step further.

The reason why Medicare has to accept prices from a single drug company, as opposed to choosing among competing producers, is that the government gives drug companies patent monopolies on drugs. Under the rules of these monopolies, a pharmaceutical company can have competitors fined or even imprisoned, if they produce a drug over which the company has patent rights.

The granting of patent monopolies is a way that the government has chosen to finance research and development in pharmaceuticals. (It also spends more than $30 billion a year financing biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health.) It could opt for other methods of financing research.

For example, Bernie Sanders proposed a prize fund to buy the rights to useful drug patents, following a model developed by Joe Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize winning economist. Under this proposal, pharmaceutical companies would be paid for their research, but the drug itself could then be sold in a free market like most other products.

In this situation, almost all drugs would be cheap. We wouldn’t have to debate whether it was worth paying $100,000 or $200,000 for a drug that could extend someone’s life by 2–3 years. The drugs would instead cost a few hundred dollars, making the decision a no-brainer.

There are other mechanisms for financing the research. We could simply have the government finance clinical trials, after buying up the rights for promising compounds. In this case also approved drugs could be sold at free market prices.

There are undoubtedly other schemes that can be devised that pay for research without giving drug companies monopolies over the distribution of the drug. Obviously we do have to pay for the research, but we don’t have to use the current patent system. It is like paying the firefighters when they show up at the burning house with our family inside. Of course we would pay them millions to save our family (if we had the money), but it is nutty to design a system that puts us in this situation.

Anyhow, if we are having a debate on drug prices, we shouldn’t just be talking about how to get lower prices under the current system. We should also be talking about changing the system.

Addendum:

For those who want more background on the Sanders Bill, here are a few pieces from James Love at Knowledge Ecology International, who worked with Sanders’ staff in drafting the bill.

Margot Sanger-Katz had a NYT Upshot column arguing that Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders plans to have Medicare negotiate drug prices ultimately won’t prove successful in lowering costs because Medicare can’t simply refuse to pay for a drug. There is much truth to this argument, but it is worth working through the dynamics a step further.

The reason why Medicare has to accept prices from a single drug company, as opposed to choosing among competing producers, is that the government gives drug companies patent monopolies on drugs. Under the rules of these monopolies, a pharmaceutical company can have competitors fined or even imprisoned, if they produce a drug over which the company has patent rights.

The granting of patent monopolies is a way that the government has chosen to finance research and development in pharmaceuticals. (It also spends more than $30 billion a year financing biomedical research through the National Institutes of Health.) It could opt for other methods of financing research.

For example, Bernie Sanders proposed a prize fund to buy the rights to useful drug patents, following a model developed by Joe Stiglitz, the Nobel Prize winning economist. Under this proposal, pharmaceutical companies would be paid for their research, but the drug itself could then be sold in a free market like most other products.

In this situation, almost all drugs would be cheap. We wouldn’t have to debate whether it was worth paying $100,000 or $200,000 for a drug that could extend someone’s life by 2–3 years. The drugs would instead cost a few hundred dollars, making the decision a no-brainer.

There are other mechanisms for financing the research. We could simply have the government finance clinical trials, after buying up the rights for promising compounds. In this case also approved drugs could be sold at free market prices.

There are undoubtedly other schemes that can be devised that pay for research without giving drug companies monopolies over the distribution of the drug. Obviously we do have to pay for the research, but we don’t have to use the current patent system. It is like paying the firefighters when they show up at the burning house with our family inside. Of course we would pay them millions to save our family (if we had the money), but it is nutty to design a system that puts us in this situation.

Anyhow, if we are having a debate on drug prices, we shouldn’t just be talking about how to get lower prices under the current system. We should also be talking about changing the system.

Addendum:

For those who want more background on the Sanders Bill, here are a few pieces from James Love at Knowledge Ecology International, who worked with Sanders’ staff in drafting the bill.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

In today’s column he makes a pitch for Republican tax reform telling readers:

“If there is going to be growth-igniting tax reform — and if there isn’t, American politics will sink deeper into distributional strife — Brady [Representative Kevin Brady, the chair of the House Ways and Means Committee] will begin it. Fortunately, the Houston congressman is focused on this simple arithmetic: Three percent growth is not 1 percent better than 2 percent growth, it is 50 percent better.

“If the Obama era’s average annual growth of 2.2 percent becomes the “new normal,” over the next 50 years real gross domestic product will grow from today’s $16.3 trillion (in 2009 dollars) to $48.3 trillion. If, however, growth averages 3.2 percent, real GDP in 2065 will be $78.6 trillion. At 2.2 percent growth, the cumulative lost wealth would be $521 trillion.”

Of course 3.2 percent growth would lead to much more output than 2.2 percent growth. The problem is that there is no way on earth that any tax reform plan will add a full percentage point to growth. It would be an enormous success if a tax reform plan added 0.2–0.3 percentage points to growth.

While it is nice that Mr. Will can do compounding of growth rates, but we don’t have tax policies that will raise the growth rate by this amount even if we managed to over-ride every interest group that benefits from their special tax breaks.

So it’s nice that Republicans still want to believe in fairy tales, but those who are old enough to remember the Reagan tax cuts and the George W. Bush tax cuts or are slightly familiar with economics know better than to buy Mr. Will’s wild fables.

In today’s column he makes a pitch for Republican tax reform telling readers:

“If there is going to be growth-igniting tax reform — and if there isn’t, American politics will sink deeper into distributional strife — Brady [Representative Kevin Brady, the chair of the House Ways and Means Committee] will begin it. Fortunately, the Houston congressman is focused on this simple arithmetic: Three percent growth is not 1 percent better than 2 percent growth, it is 50 percent better.

“If the Obama era’s average annual growth of 2.2 percent becomes the “new normal,” over the next 50 years real gross domestic product will grow from today’s $16.3 trillion (in 2009 dollars) to $48.3 trillion. If, however, growth averages 3.2 percent, real GDP in 2065 will be $78.6 trillion. At 2.2 percent growth, the cumulative lost wealth would be $521 trillion.”

Of course 3.2 percent growth would lead to much more output than 2.2 percent growth. The problem is that there is no way on earth that any tax reform plan will add a full percentage point to growth. It would be an enormous success if a tax reform plan added 0.2–0.3 percentage points to growth.

While it is nice that Mr. Will can do compounding of growth rates, but we don’t have tax policies that will raise the growth rate by this amount even if we managed to over-ride every interest group that benefits from their special tax breaks.

So it’s nice that Republicans still want to believe in fairy tales, but those who are old enough to remember the Reagan tax cuts and the George W. Bush tax cuts or are slightly familiar with economics know better than to buy Mr. Will’s wild fables.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

What else is new? Yep, the deficit is exploding and it will devastate our children and no one will listen:

“Based on the campaign so far, this important conversation seems unlikely. The leading candidates are playing Russian roulette with the nation’s future, assuming that deficits can be ignored because most Americans (or so it seems) would prefer it that way.”

Folks who pay attention to the economy might notice that the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is now under 2.0 percent. Apparently it’s not just the politicians, the financial markets are not too concerned about the deficit either.

As far as the burden on our kids, interest on the debt (net of transfers from the Federal Reserve Board) comes to less than 0.8 percent of GDP. By comparison, interest payments were over 3.0 percent of GDP in the early 1990s condemning us to a decade of stagnation. (Oh wait, doesn’t seem to have worked out that way.)

If we are concerned about helping our kids, how about running larger deficits to employ their parents? More spending on infrastructure, education, health care and other needs would help to make the labor market tight enough so that workers have the bargaining power they need to get higher wages. It would also make the economy more productive in the future.

The risk to our children from having parents without the ability to care for them dwarfs any risk they face from higher interest payments on the debt. But hey, without Robert Samuelson they might not even have someone to tell them about the debt.

What else is new? Yep, the deficit is exploding and it will devastate our children and no one will listen:

“Based on the campaign so far, this important conversation seems unlikely. The leading candidates are playing Russian roulette with the nation’s future, assuming that deficits can be ignored because most Americans (or so it seems) would prefer it that way.”

Folks who pay attention to the economy might notice that the interest rate on 10-year Treasury bonds is now under 2.0 percent. Apparently it’s not just the politicians, the financial markets are not too concerned about the deficit either.

As far as the burden on our kids, interest on the debt (net of transfers from the Federal Reserve Board) comes to less than 0.8 percent of GDP. By comparison, interest payments were over 3.0 percent of GDP in the early 1990s condemning us to a decade of stagnation. (Oh wait, doesn’t seem to have worked out that way.)

If we are concerned about helping our kids, how about running larger deficits to employ their parents? More spending on infrastructure, education, health care and other needs would help to make the labor market tight enough so that workers have the bargaining power they need to get higher wages. It would also make the economy more productive in the future.

The risk to our children from having parents without the ability to care for them dwarfs any risk they face from higher interest payments on the debt. But hey, without Robert Samuelson they might not even have someone to tell them about the debt.

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión

Read More Leer más Join the discussion Participa en la discusión